DISSOLUTE SELF-PORTRAITS in SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY DUTCH and FLEMISH ART In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIMON DE VOS (1603 – Antwerp – 1676)

CS0371 SIMON DE VOS (1603 – Antwerp – 1676) The Lamentation Signed and dated, lower left: S. D Vos. in et F 1644 Oil on panel, 14½ x 17⅝ ins. (36.8 x 44.8 cm) PROVENANCE With James A. Gorry, Dublin, until Anonymous sale, Christie’s, London, 6 October, 1950, lot 123 Anonymous sale, Christie’s, London, 9 July 2014, lot 159 (The Property of a Lady) Private collection, England, until 2021 Born in Antwerp in 1603, Simon de Vos studied with the portraitist Cornelis de Vos (1603- 1676) before enrolling as a master in the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke in 1620. Subsequently, he is thought to have rounded off his education with a trip to Italy. Although undocumented, a sojourn in Italy during the 1620s is the only plausible explanation for the stylistic similarities that exist between some of his early genre scenes and those of the German-born artist Johann Liss (c. 1595-1631), who was in Rome and Venice at that time. In any event, de Vos was back in his hometown by 1627, the year in which he married Catharina, sister of the still-life painter Adriaen van Utrecht (1599-1652). He remained in Antwerp for the rest of his life. In his early career, Simon de Vos painted mostly cabinet-sized genre scenes. He specialised in merry company subjects, whose style and composition recall similar works by such Dutch contemporaries as Antonie Palamedesz. (1601-1673), Dirck Hals (1591-1656) and Pieter Codde (1599-1678). After about 1640, he turned increasingly to biblical subjects that show the influence of Frans Francken the Younger (1581-1642), Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641). -

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn 1606-1669 REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN, born 15 July er (1608-1651), Govaert Flinck (1615-1660), and 1606 in Leiden, was the son of a miller, Harmen Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), worked during these Gerritsz. van Rijn (1568-1630), and his wife years at Van Uylenburgh's studio under Rem Neeltgen van Zuytbrouck (1568-1640). The brandt's guidance. youngest son of at least ten children, Rembrandt In 1633 Rembrandt became engaged to Van was not expected to carry on his father's business. Uylenburgh's niece Saskia (1612-1642), daughter Since the family was prosperous enough, they sent of a wealthy and prominent Frisian family. They him to the Leiden Latin School, where he remained married the following year. In 1639, at the height of for seven years. In 1620 he enrolled briefly at the his success, Rembrandt purchased a large house on University of Leiden, perhaps to study theology. the Sint-Anthonisbreestraat in Amsterdam for a Orlers, Rembrandt's first biographer, related that considerable amount of money. To acquire the because "by nature he was moved toward the art of house, however, he had to borrow heavily, creating a painting and drawing," he left the university to study debt that would eventually figure in his financial the fundamentals of painting with the Leiden artist problems of the mid-1650s. Rembrandt and Saskia Jacob Isaacsz. van Swanenburgh (1571 -1638). After had four children, but only Titus, born in 1641, three years with this master, Rembrandt left in 1624 survived infancy. After a long illness Saskia died in for Amsterdam, where he studied for six months 1642, the very year Rembrandt painted The Night under Pieter Lastman (1583-1633), the most impor Watch (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). -

Gary Schwartz

Gary Schwartz A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings as a Test Case for Connoisseurship Seldom has an exercise in connoisseurship had more going for it than the world-famous Rembrandt Research Project, the RRP. This group of connoisseurs set out in 1968 to establish a corpus of Rembrandt paintings in which doubt concer- ning attributions to the master was to be reduced to a minimum. In the present enquiry, I examine the main lessons that can be learned about connoisseurship in general from the first three volumes of the project. My remarks are limited to two central issues: the methodology of the RRP and its concept of authorship. Concerning methodology,I arrive at the conclusion that the persistent appli- cation of classical connoisseurship by the RRP, attended by a look at scientific examination techniques, shows that connoisseurship, while opening our eyes to some features of a work of art, closes them to others, at the risk of generating false impressions and incorrect judgments.As for the concept of authorship, I will show that the early RRP entertained an anachronistic and fatally puristic notion of what constitutes authorship in a Dutch painting of the seventeenth century,which skewed nearly all of its attributions. These negative judgments could lead one to blame the RRP for doing an inferior job. But they can also be read in another way. If the members of the RRP were no worse than other connoisseurs, then the failure of their enterprise shows that connoisseurship was unable to deliver the advertised goods. I subscribe to the latter conviction. This paper therefore ends with a proposal for the enrichment of Rembrandt studies after the age of connoisseurship. -

Het Gulden Cabinet Van De Edel Vry Schilderconst Cornelis De Bie, Het Gulden Cabinet Van De Edel Vry Schilderconst 244

Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst Cornelis de Bie bron Cornelis de Bie, Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst. Jan Meyssens, Juliaen van Montfort, Antwerpen 1662 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/bie_001guld01_01/colofon.php © 2014 dbnl 1 Het gulden cabinet vande edele vry schilder-const Ontsloten door den lanck ghevvenschten Vrede tusschen de twee mach- tighe Croonen van SPAIGNIEN EN VRANCRYCK, Waer-inne begrepen is den ontsterffe- lijcken loff vande vermaerste Constminnende Geesten ENDE SCHILDERS Van dese Eeuvv, hier inne meest naer het leven af-gebeldt, verciert met veel ver- makelijcke Rijmen ende Spreucken. DOOR Cornelis de Bie Notaris binnen Lyer. Cornelis de Bie, Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst 3 Den geboeyden Mars spreckt op d'uytleggingh van de titel plaet. WEl wijckt dan mijne Macht, en Raserny ter sijden? Moet mijne wreetheyt nu dees boose schant-vleck lijden? Dat ick hier ligh gheboyt en plat ter aert ghedruckt, Ontrooft van Sweert en Schilt, t'gen' my is af-geruckt? Alleen door liefdens kracht, die Vranckrijck heeft ontsteken, Die door het Echts verbont compt al mijn lusten breken, Die selffs de wreetheyt ben, wordt hier van liefd' gheplaegt, Den dullen Orloghs Godt wordt van den Peys verjaeght. Ach! d' Edel Fransche Trouw: (aen Spaenien verbonden:) Die heeft m' allendigh Helt in ballinckschap ghesonden. K' en heb niet eenen vriendt, men danckt my spoedigh aff Een jeder my verstoot, ick sien ick moet in't graff. Nochtans sal menich mensch mijn ongeluck beclaghen Die was ghewoon door my heel Belgica te plaeghen, Die was ghewoon met my te liggen op het landt Dat ick had uyt gheput door mijnen Orloghs brandt, De deught had ick verjaeght, en liefdens kracht ghenomen Midts dat mijn fury was in Neder-landt ghecomen Tot voordeel vanden Frans, die my nu brenght in druck En wederleyt mijn jonst, fortuyn en groot gheluck. -

Sztuki Piękne)

Sebastian Borowicz Rozdział VII W stronę realizmu – wiek XVII (sztuki piękne) „Nikt bardziej nie upodabnia się do szaleńca niż pijany”1079. „Mistrzami malarstwa są ci, którzy najbardziej zbliżają się do życia”1080. Wizualna sekcja starości Wiek XVII to czas rozkwitu nowej, realistycznej sztuki, opartej już nie tyle na perspektywie albertiańskiej, ile kepleriańskiej1081; to również okres malarskiej „sekcji” starości. Nigdy wcześniej i nigdy później w historii europejskiego malarstwa, wyobrażenia starych kobiet nie były tak liczne i tak różnicowane: od portretu realistycznego1082 1079 „NIL. SIMILIVS. INSANO. QVAM. EBRIVS” – inskrypcja umieszczona na kartuszu, w górnej części obrazu Jacoba Jordaensa Król pije, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 1080 Gerbrand Bredero (1585–1618), poeta niderlandzki. Cyt. za: W. Łysiak, Malarstwo białego człowieka, t. 4, Warszawa 2010, s. 353 (tłum. nieco zmienione). 1081 S. Alpers, The Art of Describing – Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago 1993; J. Friday, Photography and the Representation of Vision, „The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism” 59:4 (2001), s. 351–362. 1082 Np. barokowy portret trumienny. Zob. także: Rembrandt, Modląca się staruszka lub Matka malarza (1630), Residenzgalerie, Salzburg; Abraham Bloemaert, Głowa starej kobiety (1632), kolekcja prywatna; Michiel Sweerts, Głowa starej kobiety (1654), J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Monogramista IS, Stara kobieta (1651), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 314 Sebastian Borowicz po wyobrażenia alegoryczne1083, postacie biblijne1084, mitologiczne1085 czy sceny rodzajowe1086; od obrazów o charakterze historycznodokumentacyjnym po wyobrażenia należące do sfery historii idei1087, wpisujące się zarówno w pozy tywne1088, jak i negatywne klisze kulturowe; począwszy od Prorokini Anny Rembrandta, przez portrety ubogich staruszek1089, nobliwe portrety zamoż nych, starych kobiet1090, obrazy kobiet zanurzonych w lekturze filozoficznej1091 1083 Bernardo Strozzi, Stara kobieta przed lustrem lub Stara zalotnica (1615), Музей изобразительных искусств им. -

The Dutch Golden Age: a New Aurea Ætas? the Revival of a Myth in the Seventeenth-Century Republic Geneva, 31 May – 2 June 2018

The Dutch Golden Age: a new aurea ætas? The revival of a myth in the seventeenth-century Republic Geneva, 31 May – 2 June 2018 « ’T was in dien tyd de Gulde Eeuw voor de Konst, en de goude appelen (nu door akelige wegen en zweet naauw te vinden) dropen den Konstenaars van zelf in den mond » (‘This time was the Golden Age for Art, and the golden apples (now hardly to be found if by difficult roads and sweat) fell spontaneously in the mouths of Artists.’) Arnold Houbraken, De groote schouburgh der nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen, 1718-1721, vol. II, p. 237.1 In 1719, the painter Arnold Houbraken voiced his regret about the end of the prosperity that had reigned in the Dutch Republic around the middle of the seventeenth century. He indicates this period as especially favorable to artists and speaks of a ‘golden age for art’ (Gulde Eeuw voor de Konst). But what exactly was Houbraken talking about? The word eeuw is ambiguous: it could refer to the length of a century as well as to an undetermined period, relatively long and historically undefined. In fact, since the sixteenth century, the expression gulde(n) eeuw or goude(n) eeuw referred to two separate realities as they can be distinguished today:2 the ‘golden century’, that is to say a period that is part of history; and the ‘golden age’, a mythical epoch under the reign of Saturn, during which men and women lived like gods, were loved by them, and enjoyed peace and happiness and harmony with nature. -

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of Semester

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of semester Rosenberg, Jakob and Slive, Seymour . Chapter 4: Frans Hals . Dutch Art and Architecture: 1600-1800 . Rosenberg, Jakob, Slive, S.and ter Kuile, E.H. p. 30-47 . Middlesex, England; Baltimore, MD . Penguin Books . 1966, 1972 . Call Number: ND636.R6 1966 . ISBN: . The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or electronic reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or electronic reproduction of copyrighted materials that is to be "used for...private study, scholarship, or research." You may download one copy of such material for your own personal, noncommercial use provided you do not alter or remove any copyright, author attribution, and/or other proprietary notice. Use of this material other than stated above may constitute copyright infringement. http://library.umbc.edu/reserves/staff/bibsheet.php?courseID=5869&reserveID=16583[8/18/2016 12:48:14 PM] f t FRANS HALS: EARLY WORKS 1610-1620 '1;i no. l6II, destroyed in the Second World War; Plate 76n) is now generally accepted 1 as one of Hals' earliest known works. 1 Ifit was really painted by Hals - and it is difficult CHAPTER 4 to name another Dutch artist who used sucli juicy paint and fluent brushwork around li this time - it suggests that at the beginning of his career Hals painted pictures related FRANS HALS i to Van Mander's genre scenes (The Kennis, 1600, Leningrad, Hermitage; Plate 4n) ~ and late religious paintings (Dance round the Golden Calf, 1602, Haarlem, Frans Hals ·1 Early Works: 1610-1620 Museum), as well as pictures of the Prodigal Son by David Vinckboons. -

Garland of Flowers by Abraham Mignon

Garland of Flowers by Abraham Mignon Magdalena Kraemer-Noble This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: figs. 1, 14 and 15 By courtesy of Richard Green, London: fig. 9 By courtesy of Magdalena Kraemer-Noble: figs. 4, 10 and 12 By courtesy of Johnny Van Haeften, London: fig. 8 © Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Elke Estel, Hans-Peter Klut: figs. 5 and 6 © Horta Auctioneers, Brussels: fig. 11 © MBA Lyon / Alain Basset: fig. 3 © Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid: fig. 7 © Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis, The Hague: figs. 2 and 13 © Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe: fig. 16 © Tim Koster, ICN, Rijswijk/Amsterdam: fig. 17 Text published in: B’08 : Buletina = Boletín = Bulletin. Bilbao : Bilboko Arte Eder Museoa = Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao = Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 4, 2009, pp. 195-237. efore studying the opulent Garland of Flowers [fig. 1] in the Museum’s collection, it would be of prior in- terest to explore the challenging life of the Baroque painter Abraham Mignon who is unknown in Spain Bexcept this still-life in Bilbao. -

The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

ART AND BUSINESS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES: THE COLLECTING, DEALING AND PATRONAGE PRACTICES OF GASPARE ROOMER by Chantelle Lepine-Cercone A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (November, 2014) Copyright ©Chantelle Lepine-Cercone, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural influence of the seventeenth-century Flemish merchant Gaspare Roomer, who lived in Naples from 1616 until 1674. Specifically, it explores his art dealing, collecting and patronage activities, which exerted a notable influence on Neapolitan society. Using bank documents, letters, artist biographies and guidebooks, Roomer’s practices as an art dealer are studied and his importance as a major figure in the artistic exchange between Northern and Sourthern Europe is elucidated. His collection is primarily reconstructed using inventories, wills and artist biographies. Through this examination, Roomer emerges as one of Naples’ most prominent collectors of landscapes, still lifes and battle scenes, in addition to being a sophisticated collector of history paintings. The merchant’s relationship to the Spanish viceregal government of Naples is also discussed, as are his contributions to charity. Giving paintings to notable individuals and large donations to religious institutions were another way in which Roomer exacted influence. This study of Roomer’s cultural importance is comprehensive, exploring both Northern and Southern European sources. Through extensive use of primary source material, the full extent of Roomer’s art dealing, collecting and patronage practices are thoroughly examined. ii Acknowledgements I am deeply thankful to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sebastian Schütze. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

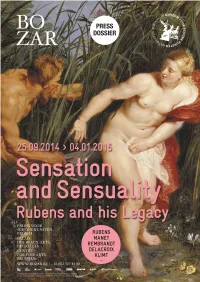

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Wyznawcy Bachusa – O Grupie Bentvueghels

uart ↪Q Nr 3(41)/2016 il. 1 Inicjacja w Bentvueghels (Inauguration of a New Member of the Bentvueghels in Rome) ok. 1660, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (autor nieznany) /40/ Kamil Kościelski / Wyznawcy Bachusa – o grupie Bentvueghels Wyznawcy Bachusa – o grupie Bentvueghels Kamil Kościelski Uniwersytet Wrocławski od koniec XV w. Półwysep Apeniński był istotnym przystankiem � 1 http://www.hadrianus.it/groups/ Pna drodze wielu szlaków handlowych, dzięki czemu region ten bentvueghels (data dostępu: 15 II 2016). przeżywał dynamiczny rozwój gospodarczy. Sprzyjająca koniunktu- 2 Ibidem. ra w pozytywny sposób wpływała na rozkwit życia kulturalnego we 3 Włoszech. Florencja, Rzym, Wenecja i Mediolan stały się ważnymi Ibidem. ośrodkami sztuki. W XVI i XVII w. Włochy stanowiły cel podróży studyjnych wielu holenderskich i flamandzkich artystów (wśród nich m.in. Peter Paul Rubens oraz członkowie rodziny Breughlów), którzy pragnęli zgłębić dzieła oraz tajniki warsztatu uznanych twór- ców. Na tym tle formowała się w Rzymie grupa określana mianem Bentvueghels. Stowarzyszenie to skupiało artystów zagranicznego pochodzenia – głównie holenderskiego i flamandzkiego. Nawiązuje do tego nazwa grupy, tłumaczona na język angielski jako Birds of a Feather (‘ptaki identycznego pióra’). Określenie Bentvueghels wią- że się z idiomem „Birds of a Feather Flock Together”, który oznacza, że ptaki o podobnym upierzeniu trzymają się razem. Stowarzyszenie było również znane pod nazwą Schildersbent, co można przełożyć jako ‘klika malarzy’. Członkami grupy bywali też jednak przedsta- wiciele innych sztuk i cechów rzemieślniczych – wśród nich rysow- nicy, grawerzy, rzeźbiarze, złotnicy, a nawet poeci 1. Szacuje się, że w ciągu całego okresu działalności stowarzyszenia (1620–1720) nale- żało do niego łącznie około 480 osób 2. Żyły one głównie w okolicach czterech rzymskich parafii – Santa Maria del Popolo, Sant’Andrea delle Fratte, San Lorenzo in Lucina oraz Santa Lucia della Tinta. -

"MAN with a BEER KEG" ATTRIBUTED to FRANS HALS TECHNICAL EXAMINATION and SOME ART HISTORICAL COMMENTARIES • by Daniel Fabian

Centre for Conservation and Technical Studies Fogg Art Museum Harvard University 1'1 Ii I "MAN WITH A BEER KEG" ATTRIBUTED TO FRANS HALS TECHNICAL EXAMINATION AND SOME ART HISTORICAL COMMENTARIES • by Daniel Fabian July 1984 ___~.~J INDEX Abst act 3 In oduction 4 ans Hals, his school and circle 6 Writings of Carel van Mander Technical examination: A. visual examination 11 B ultra-violet 14 C infra-red 15 D IR-reflectography 15 E painting materials 16 F interpretatio of the X-radiograph 25 G remarks 28 Painting technique in the 17th c 29 Painting technique of the "Man with a Beer Keg" 30 General Observations 34 Comparison to other paintings by Hals 36 Cone usions 39 Appendix 40 Acknowl ement 41 Notes and References 42 Bibliog aphy 51 ---~ I ABSTRACT The "Man with a Beer Keg" attributed to Frans Hals came to the Centre for Conservation and Technical Studies for technical examination, pigment analysis and restoration. A series of samples was taken and cross-sections were prepared. The pigments and the binding medium were identified and compared to the materials readily available in 17th century Holland. Black and white, infra-red and ultra-violet photographs as well as X-radiographs were taken and are discussed. The results of this study were compared to 17th c. materials and techniques and to the literature. 3 INTRODUCTION The "Man with a Beer Keg" (oil on canvas 83cm x 66cm), painted around 1630 - 1633) appears in the literature in 1932. [1] It was discovered in London in 1930. It had been in private hands and was, at the time, celebrated as an example of an unsuspected and startling find of an old master.