Fund for a Free South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOLOMON MAHLANGU FREEDOM COLLEGE: a Unique South African Educational Experience in Tanzania

ARTICLE SOLOMON MAHLANGU FREEDOM COLLEGE: A Unique South African Educational Experience In Tanzania Pethu Serote Introduction On the 9th July 1992, the African National Congress (ANC) handed over its educational institutions in Tanzania to the Tanzanian goverment in a ceremony officiated over by OR Tambo for the ANC and President Hassan Mwinyi for the Tanzanian government. In this article, I'd like to look briefly at these ANC educa- tional projects in Morogoro, Tanzania. My focus will be broadly their nature and the problems that impacted on their development in the ten years between 1979-1989. I would like to acknowledge the limitations of a study of this nature in such a short presentation. These events were taking place in Tanzania and most of the documen- tation needed to make the study complete is in the process of being transferred to South Africa and this has in some way limited it to whatever documents are available to the author in South Africa and to her personal experiences as a secondary school teacher and later head of adult education division in SOMAFCO from 1983 and 1990. Although this article is about two educational project of the ANC in Tanzania, Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College (SOMAFCO), and the ANC Development Centre, I have chosen SOMAFCO for the title because that was the original project and the name has also become famous in South Africa and abroad. The Establishment of SOMAFCO and the ANC Development Centre SOMAFCO was the ANC school in Morogoro, Tanzania. It was built on a 250ha piece of land in Mazimbu, an old sisal farm which the Tanzanian government gave to the ANC for this purpose. -

Part 1 Envisioning

part 1 Envisioning ∵ Danai S. Mupotsa - 9789004356368 Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 04:01:29AM via free access <UN> Danai S. Mupotsa - 9789004356368 Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 04:01:29AM via free access chapter 2 A Question of Power Danai S. Mupotsa Introduction In this essay, I reflect on the 2015 and early 2016 student activism at the Uni- versity of the Witwatersrand, in the context of a national movement in South Africa. I am particularly interested in questions of form, narrative and aesthet- ics. Many of the acts of protest have been circulated through digital technolo- gies offering a wide audience access to the events through spectacular images. These events have also been assembled and articulated through specific kinds of form, such as the autobiographical – where students invoke the category ‘I’ to articulate aspects of private life that animate their moves against structural injustices. I read these various animations of ‘the political’ in the same register that I read the novel, A Question of Power by Bessie Head (1974). While I do not offer a close textual reading of the novel, I propose that we read the various scenes of refusal animated by these students through an autobiographical lens that, like Head’s novel, offers us a splintered category of ‘I’ that both demands a politics of recognition while simultaneously refusing and disrupting the pos- sibilities of that very wish. Bessie Head’s (1974) partly autobiographical account stays with me be- cause of the ways a range of spectacular structural injustices are narrativized through a powerful dialogue between the public and the private. -

Download This Report

Military bases and camps of the liberation movement, 1961- 1990 Report Gregory F. Houston Democracy, Governance, and Service Delivery (DGSD) Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) 1 August 2013 Military bases and camps of the liberation movements, 1961-1990 PREPARED FOR AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY: FUNDED BY: NATIONAL HERITAGE COUNCI Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... iii Chapter 1: Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: Literature review ........................................................................................................4 Chapter 3: ANC and PAC internal camps/bases, 1960-1963 ........................................................7 Chapter 4: Freedom routes during the 1960s.............................................................................. 12 Chapter 5: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1960s ............................................ 21 Chapter 6: Freedom routes during the 1970s and 1980s ............................................................. 45 Chapter 7: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1970s and 1980s ........................... 57 Chapter 8: The ANC’s prison camps ........................................................................................ -

1 Pointing to the Dead: Victims, Martyrs and Public Memory In

Pointing to the Dead: Victims, Martyrs and Public Memory in South Africa Sabine Marschall Introduction Memorials are never erected for the sake of the dead, who demand our respect. Rather, they are set up by the living for the sake of the living. A memorial constitutes a ‘transitional object’ that facilitates the process of mourning for those immediately affected by the death of their loved ones and allows them to attain a sense of closure. For those in society not directly bereaved, notably later generations, the erection of a memorial in tribute to a departed leader or a select group of deceased establishes and publicly advertises a lasting, visible link with the dead they have chosen to honour. In times of political transition, the public commemoration, especially through lasting memorials, of selected dead heroes, shooting victims or fallen comrades can be a strategic move to legitimate the emergence of a new socio-political order. The recognition of the use value of specific ‘dead bodies’ is part of a larger process of appropriating the past for the political, social, cultural or economic purposes of the present, which many scholars see as a key characteristic of ‘heritage’.1 This political and functionalist perspective is not meant to invalidate the sense of duty to pay tribute to the dead that many individuals and organizations may genuinely experience. It does not discount the emotional contentment that the establishment of a dignified public memorial may evoke especially in those individuals who knew the deceased or were directly affected by their death. It also does not intent to question the role of such memorials in teaching the younger generation and instilling a sense of respect and gratitude for those who lost their lives for the attainment of a better life for all. -

Education for Liberation: the Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College: 10 Years, 1979–1989

Education for Liberation: The Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College: 10 Years, 1979–1989 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nizap1065 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Education for Liberation: The Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College: 10 Years, 1979–1989 Publisher ANC Department of Education Date 1989-00-00 Resource type Pamphlets Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, Tanzania, United Republic of, Netherlands Coverage (temporal) 1979 - 1989 Source NIZA Description Illustrated ANC publication, made with the -

Time Travel on Solomon Mahlangu

Time Travel on Solomon Mahlangu Goals • Create awareness of the life of Solomon Mahlangu and his contribution to the struggle • Reflect on the importance of human rights, in the 70s and today • Promote the Time Travel method Facts, Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu was born on 10 July 1956 in Doornkoop, Middelburg which was then known as Eastern Transvaal. He was the last born son of Martha Mahlangu’s six children of three girls and three boys. His middle name Kalushi, given by his uncle means ”one who leads boys into manhood’. Solomon Mahlangu attended Mamelodi High School up to Standard 08, but his education was interrupted in 1976 by the Soweto uprisings that resulted in school closure. This fuelled him to join and pursue the struggle. In 1976 he fled to Mozambique and spent six months in a refugee camp near XaiXai. From there he was taken to an ANC training camp called “Engineering” in Angola, where he received training in sabotage, military combat, scouting and politics . After their training at Funda Camp; Solomon Mahlangu and his comrades George Lucky Mahlangu and Mondy Motloung went to Swaziland where they crossed the border into South Africa heavily armed. They made their way to Johannesburg to assist in the student protests. On the 13 June 1977, Solomon Mahlangu and his companions Mondy Motloung and George Lucky Mahlangu, were accosted by police in Goch Street, Joburg. In the gun battle that followed, Lucky Mahlangu escaped, resulting in two civilian men being killed and two wounded. Solomon Mahlangu and Mondy Motloung were incarcerated. -

THE QUEST for FREE EDUCATION in SOUTH AFRICA How Close Is the Dream to the Reality?

Centre for Education Policy Development THE QUEST FOR FREE EDUCATION IN SOUTH AFRICA How close is the dream to the reality? R. Cassius Lubisi, PhD Solomon Mahlangu Education Lecture 2008 Constitution Hill, 17 June 2008 1 Centre for Education Policy Development THE QUEST FOR FREE EDUCATION IN SOUTH AFRICA How close is the dream to the reality? R. Cassius Lubisi, PhD 1 Solomon Mahlangu Education Lecture 2008 Constitution Hill, Johannesburg 17 June 2008 1 Dr Lubisi is the Superintendent General of Education in KwaZulu-Natal. 2 Published by the Centre for Education Policy Development PO Box 31892 Braamfontein 2017 Johannesburg South Africa Tel: +27 11 403-6131 Fax: +27 11 403-1130 CEPD Website: http://www.cepd.org.za Copyright © CEPD 2008 ISBN: 978-0-9814095-4-2 Design: Mad Cow Studio All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without prior written permission of both the copyright holder and the publishers of the book. 3 Foreword Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu was a young liberation movement activist who left South Africa in the wake of the June 1976 Soweto Uprising. On re-entering South Africa as a militant of Umkhonto we Sizwe, he and a colleague, Mondy Motloung, were captured after a skirmish with the police and several white civilians who were assisting them. Two of the civilians were killed. Although the judge found that Solomon had personally played no direct part in killing them (either by shooting or throwing a hand grenade), he was found guilty of murder through ‘common purpose’ and sentenced to death. -

Journal of African Elections Special Issue South Africa’S 2014 Elections

remember to change running heads VOLUME 14 NO 1 i Journal of African Elections Special Issue South Africa’s 2014 Elections GUEST EDITORS Mcebisi Ndletyana and Mashupye H Maserumule This issue is published by the Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa (EISA) in collaboration with the Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection (MISTRA) and the Tshwane University of Technology ARTICLES BY Susan Booysen Sithembile Mbete Ivor Sarakinsky Ebrahim Fakir Mashupye H Maserumule, Ricky Munyaradzi Mukonza, Nyawo Gumede and Livhuwani L Ndou Shauna Mottiar Cherrel Africa Sarah Chiumbu Antonio Ciaglia Mcebisi Ndletyana Volume 14 Number 1 June 2015 i ii JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS Published by EISA 14 Park Road, Richmond Johannesburg South Africa P O Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa Tel: +27 (0) 11 381 6000 Fax: +27 (0) 11 482 6163 e-mail: [email protected] ©EISA 2015 ISSN: 1609-4700 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher Printed by: Corpnet, Johannesburg Cover photograph: Reproduced with the permission of the HAMILL GALLERY OF AFRICAN ART, BOSTON, MA, USA www.eisa.org.za remember to change running heads VOLUME 14 NO 1 iii EDITOR Denis Kadima, EISA, Johannesburg MANAGING AND COPY EDITOR Pat Tucker EDITORIAL BOARD Chair: Denis Kadima, EISA, Johannesburg Jørgen Elklit, Department of Political Science, University -

REPRODUCING TOXIC ELECTION CAMPAIGNS Negative Campaigning and Race-Based Politics in the Western Cape

124 JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS REPRODUCING TOXIC ELECTION CAMPAIGNS Negative Campaigning and Race-Based Politics in the Western Cape Cherrel Africa Dr Cherrel Africa is Head of the Department of Political Studies at the University of the Western Cape e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The 2014 election in the Western Cape was once again a high-stakes, fiercely-contested affair. Political parties saw the Western Cape as an ‘open race’ and the province became the centre of vigorous campaign efforts in the lead-up to the election. The African National Congress (ANC), which had lost control of the province because its vote share dropped from 45% in 2004 to 32% in 2009, hoped to unseat the Democratic Alliance (DA), which had won in 2009 by a very narrow margin (51%). The ANC felt that it had done enough to regain control of the province, especially in light of deep-seated disillusionment in many communities and the violent protests that took place prior to the election.While the ANC maintained its support base, winning votes from 33% of the provincial electorate, the type of identity-based campaign it pursued combined with other factors to work to the DA’s advantage. Despite the fact that the DA also engaged in race- based campaigning it won 59% of the provincial vote. This was obtained at the expense of small parties, who received negligible support in the 2014 election. Only the Economic Freedom Fighters and the African Christian Democratic Party won enough votes to obtain a seat each in the provincial legislature. -

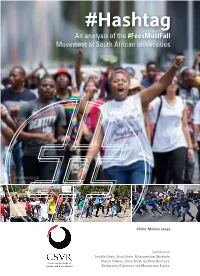

Hashtag: an Analysis of the #Feesmustfall Movement at South African Universities

#Hashtag An analysis of the #FeesMustFall Movement at South African universities Editor: Malose Langa Contributors: Sandile Ndelu, Yingi Edwin, Musawenkosi Malabela, Marcia Vilakazi, Oliver Meth, Godfrey Maringira, Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation Simbarashe Gukurume and Muneinazvo Kujeke. Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation Johannesburg Office: 33 Hoofd Street, Braampark Forum 5, 3rd Floor Johannesburg, 2001, South Africa P O Box 30778, Braamfontein, Johannesburg, 2017, South Africa Tel: +27 (11) 403-5650 Fax: +27 (11) 339-6785 e-mail: [email protected] Cape Town Office: 501 Premier Centre, 451 Main Road, Observatory, 7925 Tel: +27 (21) 447-2470 e-mail: [email protected] #Hashtag: An analysis of the #FeesMustFall Movement at South African universities Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Acronyms and abbreviations 3 Notes of contributors: 4 Researching the #FeesMustFall movement. 6 ‘A Rebellion of the Poor’: Fallism at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology 13 ‘Being Black’ in #FeesMustFall and #FreeDecolonisedEducation: Student Protests at the University of the Western Cape 33 Tshwane University of Technology: Soshanguve Campus Protests Cannot Be Reduced to #FeesMustFall 49 ‘Liberation Is a Falsehood’: Fallism at the University of Cape Town 58 Violence and the #FeesMustFall Movement at the University of KwaZulu-Natal 83 #FeesMustFall at Rhodes University: Exploring the dynamics of student protests and manifestations of violence 97 We are already enjoying free education: Protests at the University of Limpopo (Turfloop) 108 South African higher education at a crossroads: The Unizulu case study 121 We are not violent but just demanding free decolonized education: University of the Witwatersrand 132 1 # #Hashtag: An analysis of the #FeesMustFall Movement at South African universities Acknowledgements This research was undertaken following students’ protests in 2015 and 2016 in various universities in South Africa. -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Annual Report Annual Report 1985 / The flame of resistance to apartheid burned brightly in 1985. Hundreds of thousands of people-young and old, workers, teachers, priests and students-took to the streets, organized strikes and boycotts, and defied state violence and repression by using the funerals of protesters killed by the security forces to rally yet greater opposition. The South African government, mouthing empty promises of reform, struck back viciously. Over 200 children and many more hundreds of adult protesters were killed by police and soldiers; thousands of men, women and children were detained without trial; and the toll of mysterious deaths of popular leaders rose ominously. The Botha government's determination to maintain domination throughout southern Africa carried violence into neighboring countries, wreaking terrible damage in Angola, Mozambique, Namibia and Lesotho, among others. While the people on the ground in southern Africa continue to bear the brunt of the struggle for freedom, they have also called on the US to impose sanctions on apartheid in support of their demand for liberation. To bring this urgent appeal to the people of America, The Africa Fund greatly expanded its public education campaign in the US. hool for Namibia refugees in Angola. Empowering Americans to Act Against Apartheid The Africa Fund is the prime source of information on southern Africa and US policy. As Americans became aware of the evils of apartheid it was natural that they turn to The Africa Fund for the information they needed to build effective actions throughout the country: We provided the information that enabled the divestment movement to make 1985 a record year. -

Landscape of Memory

Landscape of Memory. Commemorative monuments, memorials and public statuary in post-apartheid South-Africa Marschall, S. Citation Marschall, S. (2010). Landscape of Memory. Commemorative monuments, memorials and public statuary in post-apartheid South-Africa. Brill, Leiden [etc.]. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18536 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18536 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Landscape of Memory ASC Series in collaboration with SAVUSA (South Africa – VU University Amsterdam – Strategic Alliances) Series editor Dr. Harry Wels (VU University Amsterdam, the Netherlands) Editorial board Prof. Bill Freund (University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa) Dr. Lungisile Ntsebeza (University of Cape Town, South Africa) Prof. John Sender (School for Oriental and African Studies, U.K.) Prof. Bram van de Beek (VU University Amsterdam, the Netherlands) Dr. Marja Spierenburg (VU University Amsterdam, the Netherlands) Volume 15 Landscape of Memory: Commemorative Monuments, Memorials and Public Statuary in Post-Apartheid South Africa Sabine Marschall Brill 2009 Cataloguing data ISSN ISBN © Brill Contents List of Photographs v Acknowledgements vii Abbreviations and Acronyms ix Introduction 1 Interdisciplinary perspectives on monuments 4 Monument and memorial 10 Structure of this book 12 1 Cultural Heritage Conservation and Policy 19 Introduction 19 Biased heritage landscape 20 Monuments and the ‘Soft Revolution’ 22 Developing