Naval Shipbuilding in the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Security & Defence European

a 7.90 D European & Security ES & Defence 4/2016 International Security and Defence Journal Protected Logistic Vehicles ISSN 1617-7983 • www.euro-sd.com • Naval Propulsion South Africa‘s Defence Exports Navies and shipbuilders are shifting to hybrid The South African defence industry has a remarkable breadth of capa- and integrated electric concepts. bilities and an even more remarkable depth in certain technologies. August 2016 Jamie Shea: NATO‘s Warsaw Summit Politics · Armed Forces · Procurement · Technology The backbone of every strong troop. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles. When your mission is clear. When there’s no road for miles around. And when you need to give all you’ve got, your equipment needs to be the best. At times like these, we’re right by your side. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles: armoured, highly capable off-road and logistics vehicles with payloads ranging from 0.5 to 110 t. Mobilising safety and efficiency: www.mercedes-benz.com/defence-vehicles Editorial EU Put to the Test What had long been regarded as inconceiv- The second main argument of the Brexit able became a reality on the morning of 23 campaigners was less about a “democratic June 2016. The British voted to leave the sense of citizenship” than of material self- European Union. The majority that voted for interest. Despite all the exception rulings "Brexit", at just over 52 percent, was slim, granted, the United Kingdom is among and a great deal smaller than the 67 percent the net contribution payers in the EU. This who voted to stay in the then EEC in 1975, money, it was suggested, could be put to but ignoring the majority vote is impossible. -

International Programs Key to Security Cooperation an Interview With

SURFACE SITREP Page 1 P PPPPPPPPP PPPPPPPPPPP PP PPP PPPPPPP PPPP PPPPPPPPPP Volume XXXII, Number 3 October 2016 International Programs Key to Security Cooperation An Interview with RADM Jim Shannon, USN, Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy for International Programs Conducted by CAPT Edward Lundquist, USN (Ret) Tell me about your mission, and what intellectual property of the technology you have — your team —in order to that we developed for our Navy execute that mission? programs – that includes the Marine It’s important to understand what your Corps. These are Department of Navy authorities are in any job you come Programs, for both the Navy and Marine into. You just can’t look at a title and Corps, across all domains – air, surface, determine what your job or authority subsurface, land, cyber, and space, is. In this case, there are Secretary everywhere, where the U.S. Navy or of the Navy (SECNAV) instructions; the Department of the Navy is the lead there’s law; and then there’s federal agent. As the person responsible for government regulations on how to this technology’s security, I obviously do our job. And they all imply certain have a role where I determine “who levels of authority to the military do we share that information with and departments – Army, Navy, and Air how do we disclose that information.” Force. And then the Office of the The way I exercise that is in accordance Secretary of Defense (OSD) has a with the laws, the Arms Export Control separate role, but altogether, we work Act. -

The Human Cost of Fortress Europe

THE HUMAN COST OF FORTRESS EUROPE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AGAINST MIGRANTS AND REFUGEES AT EUROPE’S BORDERS Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. This report is published as part of Amnesty International's campaign, S.0.S. Europe: people before borders. To find out more visit http://www.whenyoudontexist.eu First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: EUR 05/001/2014 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Border policemen patrol the Bulgarian-Turkish border where a 30km fence is being built to prevent migrants and refugees irregularly crossing the border into Europe. -

The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs

Jeremy Stöhs ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Jeremy Stöhs is the Deputy Director of the Austrian Center for Intelligence, Propaganda and Security Studies (ACIPSS) and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Institute for Security Policy, HOW HIGH? Kiel University. His research focuses on U.S. and European defence policy, maritime strategy and security, as well as public THE FUTURE OF security and safety. EUROPEAN NAVAL POWER AND THE HIGH-END CHALLENGE ISBN 978875745035-4 DJØF PUBLISHING IN COOPERATION WITH 9 788757 450354 CENTRE FOR MILITARY STUDIES How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Djøf Publishing In cooperation with Centre for Military Studies 2021 Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge © 2021 by Djøf Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior written permission of the Publisher. This publication is peer reviewed according to the standards set by the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science. Cover: Morten Lehmkuhl Print: Ecograf Printed in Denmark 2021 ISBN 978-87-574-5035-4 Djøf Publishing Gothersgade 137 1123 København K Telefon: 39 13 55 00 e-mail: [email protected] www. djoef-forlag.dk Editors’ preface The publications of this series present new research on defence and se- curity policy of relevance to Danish and international decision-makers. -

Directive to Joint Army-Navy Committee

ooe1~FAl({Qes . ~--~-~ • • July 31' 1940 Declassified and approved for release by NSA on 07-05-2012 pursuantto E .0. 1352a SUBJECT: Directive to Joint Army-Navy Committee TO: 1~ffiERS OF THE COM~'.ITTEE: Lieutenant Earle F. Cook, USA Lieutenijnt Robert E. Schukraft, Lt. Commander E.R. Gardner, USN Lieutenant J. A. Gr.eenwald, USN ... PURPOSE OF THE COMMITTEE: 1. To investigate the practicablility of dividing all intercept traffic of desired types between the Army and Navy by a method suggested by General Mauborgne - i.e., the distribution will be based on the assignment of individual transmitting stations to be intercepted by each serYice and the traffic then intercepted to be worked on by the particular service which intercepted it. For the purpose of this study a preliminary survey will be ma.de. See Paragrpph 4 on "Points to be Considered" below. 2. To investigate the practicability of pooling all taaffic as intercepted by the two services, and a practical method of making an equitable division of this traffic tor translation purposes. J. To investigate any other practical means by which the division of traffic between the .Army and Navy aay be divided in an equitable fashion. 4. To make recommendations on each of the plans considered: Points to be Considered: In connection with the study of tiis committee, the following points should be considered: A Present ~tatus of interception for non-miliaary traffic - German, Japanese, Italian, Russian, Mexican, Chinese stations. SECRET 3984 58 ~ rn the.ivision on transmitter st.Ion or circuit intercept basis, report is specifically desired on the following: For each circuit or transmitting station: (1) Name of intercept stations; (2) Hours covered; (3) Percentage of diplomatic traffic of desired type intercepted; (4) Equipment used for purpose; (5) Number of operators detailed for this purpose; (6) What stations of .A:rmy and Navy are best able to intercept the stations or circuits from the point of view of: (a) Geographical location; (b) Equipment and personnel. -

American Naval Policy, Strategy, Plans and Operations in the Second Decade of the Twenty- First Century Peter M

American Naval Policy, Strategy, Plans and Operations in the Second Decade of the Twenty- first Century Peter M. Swartz January 2017 Select a caveat DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. CNA’s Occasional Paper series is published by CNA, but the opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of CNA or the Department of the Navy. Distribution DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. PUBLIC RELEASE. 1/31/2017 Other requests for this document shall be referred to CNA Document Center at [email protected]. Photography Credit: A SM-6 Dual I fired from USS John Paul Jones (DDG 53) during a Dec. 14, 2016 MDA BMD test. MDA Photo. Approved by: January 2017 Eric V. Thompson, Director Center for Strategic Studies This work was performed under Federal Government Contract No. N00014-16-D-5003. Copyright © 2017 CNA Abstract This paper provides a brief overview of U.S. Navy policy, strategy, plans and operations. It discusses some basic fundamentals and the Navy’s three major operational activities: peacetime engagement, crisis response, and wartime combat. It concludes with a general discussion of U.S. naval forces. It was originally written as a contribution to an international conference on maritime strategy and security, and originally published as a chapter in a Routledge handbook in 2015. The author is a longtime contributor to, advisor on, and observer of US Navy strategy and policy, and the paper represents his personal but well-informed views. The paper was written while the Navy (and Marine Corps and Coast Guard) were revising their tri- service strategy document A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, finally signed and published in March 2015, and includes suggestions made by the author to the drafters during that time. -

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Netherlands Armed Forces a Strategic Survey

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Europe View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. -

Reference Sheet

TACTICALL NAVY REFERENCES Internal Communication External Communication TactiCall gives you complete control and fast access to all net- TactiCall is a perfect match for Task- or coalition force operations, works on board your vessel. Be it Functional Nets including teleph- including other military arms. SOF teams, air force, marine detach- ony, public address, entertainment systems and the like or Fighting ments and even civil and NGO agencies can be important players Nets handling alarms, broadcasts and orders, weapon teams or in the operation. More often than not, this setup includes a multi- mission control. tude of different frequency bands, networks and radio equipment. TactiCall will integrate all these into one simple and easy to use TactiCall is highly flexible and scalable, it is platform independent solution that permits everybody to reach each other regardless of and will integrate seamlessly into your combat management sys- equipment and technology used. tem of choice. In other words TactiCall lets you control all internal communication on board your vessel and with features such as TactiCall will allow key features for modern day operations like red/ record and playback helps you log and later analyze your commu- black separation, multi-level security operations, global public ad- nication flows. dress and allowing government or task force commanders to com- municate directly with whoever needs to be addressed in a given situation - facilitating a much smoother and more rapid “Statement of No Objections” chain. Contact Porten -

The Readiness of Canada's Naval Forces Report of the Standing

The Readiness of Canada's Naval Forces Report of the Standing Committee on National Defence Stephen Fuhr Chair June 2017 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. For greater certainty, this permission does not affect the prohibition against impeaching or questioning the proceedings of the House of Commons in courts or otherwise. The House of Commons retains the right and privilege to find users in contempt of Parliament if a reproduction or use is not in accordance with this permission. -

Enabling Cost-Effective Maritime Security

Coast Guard Focus Day: 29th September - Morning Non-Lethal Weapons Workshop: 29th September - Afternoon Main Conference: 30th September -1st October Location: Rome, Italy CELEBRATING A DECADE OF EXCELLENCE THE 10TH Annual International CONFERENCE HOSTED IN ROME, ITALY ENABLING COST-EFFECTIVE MARITIME SECURITY Admiral José A. Sierra Vice Admiral UO Jibrin Rear Admiral Rear Admiral Rear Admiral Rodríguez Chief of Staff Antonio Natale Geoffrey M Biekro Hasan ÜSTEM/Senior Director General of Naval Nigerian Navy Head of VII Dept., Ships Chief of Naval Staff representative Construction Design & Combat System Ghanaian Navy Commandant Mexican Italian Navy Turkish Coast Guard Secretariat of the Navy General Staff Attend the world’s largest event for the OPV Two pre-conference events: community and: * Half day of presentations focused on • Improve your technical understanding of the latest Coast Guard effectiveness with a particular OPV designs from both public and private sector shipyards to keep innovative and ahead of the market emphasis on Mediterranean Security • Benefit from strategic engagement with Admirals from navies and coastguards; understand their * Workshop examining armament options current mission sets in order to design OPVs for their requirements including non-lethal weaponry • Contribute ideas and solutions directly to senior officers and help shape the debate on delivering cost- More details on Page 6! effective maritime security. • Share industry and public sector lessons from recent capacity building and modernisation programmes -

Mp-Hfm-134-46

Good Practices of End of Deployment Debriefing in the Royal Netherlands Navy Commander RNLN Marten Meijer PhD NATO Research and Technology Organization, Paris, France PO Box 25, F-92201 Neuilly Sur Seine, Cedex 01, France Tel ++ 33 1 55 61 22 60 Fax ++ 33 1 55 61 96 45 [email protected] Lieutenant RNLN Rodney de Vries BA Regional Office of the Defense Social Service, Utrecht, The Netherlands PO Box 90004, 3509 AA Utrecht, The Netherlands Tel ++ 31 30 236 6424 Fax ++ 31 30 293 7224 [email protected] ABSTRACT Practices in early psychological interventions after critical incidents have been the focus of research for several years now. In an article in The Lancet in 2002, it was concluded on the basis of seven international studies that individual single session debriefing does not lead to a decline in the incidence of Post Traumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD) among the victims of accidents or traumatic events. At the international level, it was recommended that the term ‘debriefing’ should be replaced by the term ‘early intervention’, and that a stop should be put to the debriefing of victims of shocking events. The debate about early interventions in the Netherlands Armed Forces continued in 2004 in the memorandum to the State Secretary for Defense from the former Inspector-General of the Armed Forces. The Ombudsman of the Canadian Armed Forces suggested in 2004 a policy on End of Deployment Debriefings in his memorandum on Third Location Decompression, in which redeploying troops stay together on the transit home in a safe place to share experiences and expectations. -

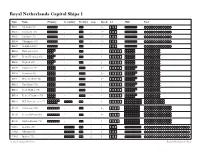

Royal Netherlands Navy Data Sheets

Royal Netherlands Capital Ships 1 Type Name Primary Secondary Tertiary Torp Speed AA Hull Fuel BB01 Oliphant (32) - - 1+ 4 2 1 BB02 Eendracht (32) - - 1+ 4 2 1 BB03 Kijkduin (32) - - 1+ 4 2 1 BB04 Vlissingen (32) - - 1+ 4 2 1 BB05 Gelijkheid (32) - - 1+ 4 2 1 BB06 Wassenaer (62) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB07 B. van Treslong (62) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB08 Vrijheid (62) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB09 Koopman (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB10 Evertsen (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB11 Witte de With (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB12 Van Ghent (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB13 Tjerk Hiddes (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB14 Reiner Claeszen (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB15 D.Z. Provencien (117) - 3 8 5 3 2 1 BC04 Floriszoon (90) - - 3+ 6 4 2 1 BC05 R. van Holland (90) - - 3+ 6 4 2 1 BC06 Gulden Phenix (90) - - 3+ 6 4 2 1 CA01 Aemilia (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 CA02 Alkmaar (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 CA03 Jupiter (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 © 2015 Avalanche Press Royal Netherlands Navy Royal Netherlands Capital Ships 2 Type Name Primary Secondary Tertiary Torp Speed AA Hull Fuel CA04 Vergulde Haan (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 CA05 Jaarsveld (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 CA06 Neptunis (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 CA07 De Kock (20) - 2 3 3 1 CA08 van Heutsz (20) - 2 3 3 1 CA09 J.P.