The Human Cost of Fortress Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Security & Defence European

a 7.90 D European & Security ES & Defence 4/2016 International Security and Defence Journal Protected Logistic Vehicles ISSN 1617-7983 • www.euro-sd.com • Naval Propulsion South Africa‘s Defence Exports Navies and shipbuilders are shifting to hybrid The South African defence industry has a remarkable breadth of capa- and integrated electric concepts. bilities and an even more remarkable depth in certain technologies. August 2016 Jamie Shea: NATO‘s Warsaw Summit Politics · Armed Forces · Procurement · Technology The backbone of every strong troop. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles. When your mission is clear. When there’s no road for miles around. And when you need to give all you’ve got, your equipment needs to be the best. At times like these, we’re right by your side. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles: armoured, highly capable off-road and logistics vehicles with payloads ranging from 0.5 to 110 t. Mobilising safety and efficiency: www.mercedes-benz.com/defence-vehicles Editorial EU Put to the Test What had long been regarded as inconceiv- The second main argument of the Brexit able became a reality on the morning of 23 campaigners was less about a “democratic June 2016. The British voted to leave the sense of citizenship” than of material self- European Union. The majority that voted for interest. Despite all the exception rulings "Brexit", at just over 52 percent, was slim, granted, the United Kingdom is among and a great deal smaller than the 67 percent the net contribution payers in the EU. This who voted to stay in the then EEC in 1975, money, it was suggested, could be put to but ignoring the majority vote is impossible. -

Symposium on Covid-19, Global Mobility and International Law

doi:10.1017/aju.2020.64 SYMPOSIUM ON COVID-19, GLOBAL MOBILITY AND INTERNATIONAL LAW FORTRESS EUROPE, GLOBAL MIGRATION & THE GLOBAL PANDEMIC John Reynolds* The European Union’s external border regime is a manifestation of continuing imperialism. It reinforces par- ticular imaginaries of Europe’s wealth as somehow innate (rather than plundered and extorted1) and of Europeanness itself as whiteness—euphemistically packaged as a “European Way of Life” to be protected.2 This exposes international law’s structural limitations—if not designs—as bound up with racial borders in the global context. In the wake of COVID-19 and with a climate apocalypse already underway, these realities need to be urgently ruptured and reimagined. Liberalism with Borders: Fortress Europe and International Law In the EU institutional worldview, Europe must be “shielded” from the threats of human mobility. The physical and administrative externalization of the EU border is designed to limit the scope for non-Europeans to legally access refuge in Europe. Those seeking to enter the EU from the Global South are cast in pejorative terms as presumed “economic migrants”—a loose category without mobility rights under international law—and rendered “illegal.” Europe’s access barriers for such communities contrast with both historical experiences of European colonial economic migrants who benefitted from an international legal regime “that facilitated, encouraged, and celebrated white economic migration,” and contemporary entitlements of First World passport holders whose global movement is expedited by a “robust web” of international visa agreements.3 People from the Third World—most of the world—are denied such arbitrary passport privilege. -

International Programs Key to Security Cooperation an Interview With

SURFACE SITREP Page 1 P PPPPPPPPP PPPPPPPPPPP PP PPP PPPPPPP PPPP PPPPPPPPPP Volume XXXII, Number 3 October 2016 International Programs Key to Security Cooperation An Interview with RADM Jim Shannon, USN, Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy for International Programs Conducted by CAPT Edward Lundquist, USN (Ret) Tell me about your mission, and what intellectual property of the technology you have — your team —in order to that we developed for our Navy execute that mission? programs – that includes the Marine It’s important to understand what your Corps. These are Department of Navy authorities are in any job you come Programs, for both the Navy and Marine into. You just can’t look at a title and Corps, across all domains – air, surface, determine what your job or authority subsurface, land, cyber, and space, is. In this case, there are Secretary everywhere, where the U.S. Navy or of the Navy (SECNAV) instructions; the Department of the Navy is the lead there’s law; and then there’s federal agent. As the person responsible for government regulations on how to this technology’s security, I obviously do our job. And they all imply certain have a role where I determine “who levels of authority to the military do we share that information with and departments – Army, Navy, and Air how do we disclose that information.” Force. And then the Office of the The way I exercise that is in accordance Secretary of Defense (OSD) has a with the laws, the Arms Export Control separate role, but altogether, we work Act. -

The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs

Jeremy Stöhs ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Jeremy Stöhs is the Deputy Director of the Austrian Center for Intelligence, Propaganda and Security Studies (ACIPSS) and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Institute for Security Policy, HOW HIGH? Kiel University. His research focuses on U.S. and European defence policy, maritime strategy and security, as well as public THE FUTURE OF security and safety. EUROPEAN NAVAL POWER AND THE HIGH-END CHALLENGE ISBN 978875745035-4 DJØF PUBLISHING IN COOPERATION WITH 9 788757 450354 CENTRE FOR MILITARY STUDIES How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Djøf Publishing In cooperation with Centre for Military Studies 2021 Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge © 2021 by Djøf Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior written permission of the Publisher. This publication is peer reviewed according to the standards set by the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science. Cover: Morten Lehmkuhl Print: Ecograf Printed in Denmark 2021 ISBN 978-87-574-5035-4 Djøf Publishing Gothersgade 137 1123 København K Telefon: 39 13 55 00 e-mail: [email protected] www. djoef-forlag.dk Editors’ preface The publications of this series present new research on defence and se- curity policy of relevance to Danish and international decision-makers. -

Directive to Joint Army-Navy Committee

ooe1~FAl({Qes . ~--~-~ • • July 31' 1940 Declassified and approved for release by NSA on 07-05-2012 pursuantto E .0. 1352a SUBJECT: Directive to Joint Army-Navy Committee TO: 1~ffiERS OF THE COM~'.ITTEE: Lieutenant Earle F. Cook, USA Lieutenijnt Robert E. Schukraft, Lt. Commander E.R. Gardner, USN Lieutenant J. A. Gr.eenwald, USN ... PURPOSE OF THE COMMITTEE: 1. To investigate the practicablility of dividing all intercept traffic of desired types between the Army and Navy by a method suggested by General Mauborgne - i.e., the distribution will be based on the assignment of individual transmitting stations to be intercepted by each serYice and the traffic then intercepted to be worked on by the particular service which intercepted it. For the purpose of this study a preliminary survey will be ma.de. See Paragrpph 4 on "Points to be Considered" below. 2. To investigate the practicability of pooling all taaffic as intercepted by the two services, and a practical method of making an equitable division of this traffic tor translation purposes. J. To investigate any other practical means by which the division of traffic between the .Army and Navy aay be divided in an equitable fashion. 4. To make recommendations on each of the plans considered: Points to be Considered: In connection with the study of tiis committee, the following points should be considered: A Present ~tatus of interception for non-miliaary traffic - German, Japanese, Italian, Russian, Mexican, Chinese stations. SECRET 3984 58 ~ rn the.ivision on transmitter st.Ion or circuit intercept basis, report is specifically desired on the following: For each circuit or transmitting station: (1) Name of intercept stations; (2) Hours covered; (3) Percentage of diplomatic traffic of desired type intercepted; (4) Equipment used for purpose; (5) Number of operators detailed for this purpose; (6) What stations of .A:rmy and Navy are best able to intercept the stations or circuits from the point of view of: (a) Geographical location; (b) Equipment and personnel. -

Building Walls: Fear and Securitization in the European Union

CENTRE DELÀS REPORT 35 Fear and securitization in the European Union Authors: Ainhoa Ruiz Benedicto · Pere Brunet Published by: Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau Carrer Erasme de Janer 8, entresol, despatx 9 08001 Barcelona T. 93 441 19 47 www.centredelas.org [email protected] This research is part of Ainhoa Ruiz Benedicto’s doctoral thesis for the “Peace, Conflict and Development” programme at Jaume I University. Researchers: Ainhoa Ruiz Benedicto, Pere Brunet Acknowledgements: Guillem Mases, Edgar Vega, Julia Mestres, Teresa de Fortuny, Cinta Bolet, Gabriela Serra, Brian Rusell, Niamh Eastwood, Mark Akkerman. Translator: María José Oliva Parada Editors: Jordi Calvo Rufanges, Nick Buxton Barcelona, September 2018 Design and layout: Esteva&Estêvão Cover photo: Stockvault; p. 11: Ashley Gilbertson/VII/Redux; p. 5: blublu.org p. 9: www.iamawake.co; p. 21: Georgi Licovski/EPA D.L.: B-19744-2010 ISSN: 2013-8032 INDEX Executive summary . 5 Foreword . 9 1 . Building walls . 12 1.1 New security policies in the border area.........................12 1.2 European border policy: towards securitization and militarisation...............................................13 1.3 The European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex).........14 2 . Mental walls . 16. 2.1 Concept and practice of fortress europe.........................16 2.2 Mental walls in Europe: the rise of racism and xenophobia ......17 3 . Physical walls . 23 3.1 Walls surrounding Europe ..................................... 23 3.2 Land walls .....................................................25 3.3 Maritime walls ................................................ 30 4 . Virtual walls . 34 4.1 Virtual walls and surveillance systems ........................ 34 4.2 Systems for the control and storage of data on movements across borders................................. 34 4.3 Surveillance system for border areas: EUROSUR............... -

The Development of the European Union in the Areas of Migration, Visa and Asylum After 2015. Priorities, Effects, Perspectives

Migration Studies – Review of Polish Diaspora nr 1 (175)/2020, http://www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Migracyjne/ DOI: 10.4467/25444972SMPP.20.004.11795 The development of the European Union in the areas of migration, visa and asylum after 2015. Priorities, effects, perspectives KATARZYNA CYMBRANOWICZ1 Department of European Studies and Economic Integration, Cracow University of Economics The article entitled ‘The development of the European Union in the areas of migration, visa and asylum after 2015. Priorities, effects, perspectives’ is a contribution to the public discourse on one of the biggest problems and challenges facing the European Union in the 21st century from a po- litical, economic and social perspective. The (un)controlled influx of refugees to Europe after 2015, which is the result of political destabilization and the unstable socio-economic situation in the re- gion of North Africa and the Middle East, clearly indicates that during the ‘test’, the existing refugee protection system in the European Union did not pass the ‘exam’. In connection with the above, attempts to modify it have been made at the EU level. This article is a presentation of individual so- lutions (‘Fortress Europe’, ‘Open Door Policy’, ‘Sluice’), as well as an analysis and evaluation of the possibilities of their implementation in the current difficult crisis conditions. Keywords: migrant, refugee, migration crisis, the European Union 1. Introduction Recent years have seen the largest wave of migration from North Africa and the Mid- dle East towards Europe2 since the end of World War II. The massive and uncontrolled influx of migrants to Europe has resulted in a crisis which became the greatest chal- lenge faced by the European Union (EU) in the second decade of the 21st century. -

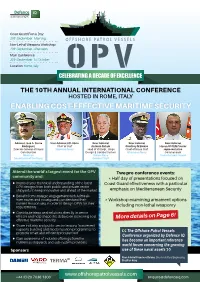

Enabling Cost-Effective Maritime Security

Coast Guard Focus Day: 29th September - Morning Non-Lethal Weapons Workshop: 29th September - Afternoon Main Conference: 30th September -1st October Location: Rome, Italy CELEBRATING A DECADE OF EXCELLENCE THE 10TH Annual International CONFERENCE HOSTED IN ROME, ITALY ENABLING COST-EFFECTIVE MARITIME SECURITY Admiral José A. Sierra Vice Admiral UO Jibrin Rear Admiral Rear Admiral Rear Admiral Rodríguez Chief of Staff Antonio Natale Geoffrey M Biekro Hasan ÜSTEM/Senior Director General of Naval Nigerian Navy Head of VII Dept., Ships Chief of Naval Staff representative Construction Design & Combat System Ghanaian Navy Commandant Mexican Italian Navy Turkish Coast Guard Secretariat of the Navy General Staff Attend the world’s largest event for the OPV Two pre-conference events: community and: * Half day of presentations focused on • Improve your technical understanding of the latest Coast Guard effectiveness with a particular OPV designs from both public and private sector shipyards to keep innovative and ahead of the market emphasis on Mediterranean Security • Benefit from strategic engagement with Admirals from navies and coastguards; understand their * Workshop examining armament options current mission sets in order to design OPVs for their requirements including non-lethal weaponry • Contribute ideas and solutions directly to senior officers and help shape the debate on delivering cost- More details on Page 6! effective maritime security. • Share industry and public sector lessons from recent capacity building and modernisation programmes -

Building Fortress Europe: the Polish-Ukrainian Frontier | Pol-Int

Pol-Int MONOGRAPH Building Fortress Europe: The Polish-Ukrainian Frontier Published: 24.10.2016 Reviewed by M.A. Johann Zajaczkowski Edited by Dr. Andriy Tyushka In the past two years, the so-called "refugee crisis" ranked high on the European political agenda. To be more precise, the very surge and scope of maritime migration flows from the turbulent terrains in the Middle East profiled domestic and EU-level politics across the European Union member states. The mere geopolitical logic of the refugees' escape routes put a worrying spotlight on the Mediterranean Sea as a natural border at the EU's southern flank. No less worrying should appear, however, the scant presence of critical voices calling to assume the responsibility 'at the EU border regime' for over 10 000 refugees, who, reportedly, had died since 2014 in their failed attempts to cross the Sea. The human facets of the tragedy either vanish under the EU-led hegemonic discourse on rational-bureaucratic models of border management or – being ipso facto part of the same discursive process – are used for delegitimizing speech acts such as the demonization of the human traffickers. [1] As a result, the policy issue as such is being incrementally dehumanized, with nasty consequences to be seen unfolding: It facilitates populist parties' attempts throughout Europe to paralyze the "rule of law-reflex" of liberal democrats, who came to form the mainstream of society. Should one succeed in coining the entirety of refugees and their movement as a sort of "fateful", "faceless mass", the tradition of inalienable human rights and enlightened individualism could be neglected much easier. -

Eftihia Voutira* Realising “Fortress Europe”: “Managing” Migrants

Eπιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών, 140-141 B´– Γ´, 2013, 57-69 Eftihia Voutira* rEaliSiNG “fortrESS EuroPE”: “MaNaGiNG” MiGraNtS aND rEfuGEES at thE BorDErS of GrEECE aBStraCt This paper considers the emergence of a migration regime in the making at the South-eastern borders of Europe with special reference to Greece and the role of FRONTEX as the new European border guard often acting in lieu of the state. Using a bio-political approach, we consider practices of human rights violations at the Greek reception centres in Evros and identify the actors involved in policing the borders. The key question is that of accountability: who guards the guards guarding Europe’s borders? Keywords: FRONTEX, migration regime, migration management, asylum seekers, refugees iNtroDuCtioN outside the village of Sidero, not far from the town of Soufli, there is a burial ground for migrants who die trying to cross the Greek-turkish bor- ders. approximately 40 people lost their lives trying to cross the borders during the first 7 months of 2010.1 the normal procedure is to transfer the bodies to the university hospital of alexandroupolis for the coroner’s ex- amination. recently, a DNa test has also been introduced so that the bodies can be identified, numbered and classified and eventual identification may be possible in the future by relatives. the international network “Welco- me2Europe” has launched a campaign accusing the Greek authorities of * Professor, Department of Balkan, Slavic and oriental Studies, university of Makedonia, thessaloniki. 1. http://w2eu.net/2010/08/09/mass-grave-of-refugees-in-evros-uncovered/ 58 ΕfΤΙηΙΑ Voutira creating mass graves to dispose of the bodies. -

Transforming Eurodac from 2016 to the New Pact

Transforming Eurodac from 2016 to the New Pact From the Dublin System’s Sidekick to a Database in Support of EU Policies on Asylum, Resettlement and Irregular Migration Author Dr Niovi Vavoula Lecturer in Migration and Security at the School of Law of Queen Mary University of London ECRE WORKING PAPER 13 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. Eurodac: The Digital Sidekick of the Dublin System 4 2.1 The Asylum-Related Functions of Eurodac 4 2.2 Law Enforcement Access to Eurodac Data 7 3. The Legal Landscape of Europe-Wide Information Systems in the area of freedom, security and justice (AFSJ) 8 3.1 Schengen Information System (SIS) 8 3.2 Visa Information System (VIS) 8 3.3 Entry/Exit System (EES) 9 3.4 European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS) 9 3.5 European Criminal Records Information System for Third-Country Nationals (ECRIS-TCN) 9 3.6 From Independent Systems to Interoperability 10 4. The 2016 Recast Eurodac Proposal 10 4.1 The Transformation of Eurodac into a Tool for Migration Purposes 11 4.2 The Interinstitutional Negotiations 13 4.3 Fundamental Rights Assessment 15 4.3.1 Widening of Purposes Without Clarity and Demonstrated Necessity 15 4.3.2 Undifferentiated Treatment Disregards the Potential Vulnerability 16 4.3.3 Concerns regarding the capturing of biometric data of children 16 4.3.4 Capturing of Data of Third-Country Nationals who have not yet entered the EU 17 4.3.5 Rationale for Including Additional Categories of Personal Data Unclear and Unsatisfying 17 4.3.6 Disproportionate Retention Period of Personal Data 18 4.3.7 Potential of International Transfers of Stored Data to Third Parties 19 4.3.8 Right to Information Improved 19 4.3.9 Removal of Important Safeguards as Regards Law Enforcement Access 20 5. -

Italy: the Deadliest Route to Fortress Europe

Italy: the Deadliest Route to Fortress Europe This report has been drawn up by the advocacy area of the Spanish Refugee Aid Commission (CEAR in Spanish) in the context of the “Observatory on the right to asylum, forced migrations and borders” project funded by the Extremadura Agency for International Development Cooperation (AEXCID). In the context of this investigation and in an aim to diagnose the current situation in Italy and the EU, the CEAR team held interviews with UNHCR, ASGI, Baobab Experience, Centro Astalli, CIR, CPR Roma, EASO, Emergency, Instituto Pedro Arrupe de Palermo, LasciateCIEntrare, Mediterranean Hope, MSF, OXFAM Italia, Save the Children, SJR, Terre des Hommes, UNICEF, Doctor Juan Federico Jiménez Carrascosa and migrant people, asylum applicants and refugees who have given a voice to their experience and real situation. Front page image: “è il cimitero dell’indifferenza”. By: Francesco Piobbichi Year and place published: 2017, Madrid The Spanish Refugee Aid Commission (CEAR) is a non-profit organisation founded in 1979 that is engaged in voluntary, humanitarian, independent and joint action. Our objective is to work with citizens to defend the right to asylum. Our mission is also to defend and promote human rights and comprehensive development for asylum applicants, refugees, stateless people and migrants in vulnerable situations or at risk of social exclusion. Our work has a comprehensive approach based on temporary accommodation; legal, psychological and social assistance; training and employment; and social advocacy