Mp-Hfm-134-46

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Editor

EDITORIAL STAFF From the Editor ELIZABETH SKINNER Editor Happy New Year, everyone. As I write this, we’re a few weeks into 2021 and there ELIZABETH ROBINSON Copy Editor are sparkles of hope here and there that this year may be an improvement over SALLY BAHO Copy Editor the seemingly endless disasters of the last one. Vaccines are finally being deployed against the coronavirus, although how fast and for whom remain big sticky questions. The United States seems to have survived a political crisis that brought EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD its system of democratic government to the edge of chaos. The endless conflicts VICTOR ASAL in Syria, Libya, Yemen, Iraq, and Afghanistan aren’t over by any means, but they have evolved—devolved?—once again into chronic civil agony instead of multi- University of Albany, SUNY national warfare. CHRISTOPHER C. HARMON 2021 is also the tenth anniversary of the Arab Spring, a moment when the world Marine Corps University held its breath while citizens of countries across North Africa and the Arab Middle East rose up against corrupt authoritarian governments in a bid to end TROELS HENNINGSEN chronic poverty, oppression, and inequality. However, despite the initial burst of Royal Danish Defence College change and hope that swept so many countries, we still see entrenched strong-arm rule, calcified political structures, and stagnant stratified economies. PETER MCCABE And where have all the terrorists gone? Not far, that’s for sure, even if the pan- Joint Special Operations University demic has kept many of them off the streets lately. Closed borders and city-wide curfews may have helped limit the operational scope of ISIS, Lashkar-e-Taiba, IAN RICE al-Qaeda, and the like for the time being, but we know the teeming refugee camps US Army (Ret.) of Syria are busy producing the next generation of violent ideological extremists. -

Federal Court Between

Court File No. T-735-20 FEDERAL COURT BETWEEN: CHRISTINE GENEROUX JOHN PEROCCHIO, and VINCENT R. R. PEROCCHIO Applicants and ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA Respondent AFFIDAVIT OF MURRAY SMITH Table of Contents A. Background 3 B. The Firearms Reference Table 5 The Canadian Firearms Program (CFP): 5 The Specialized Firearms Support Services (SFSS): 5 The Firearms Reference Table (FRT): 5 Updates to the FRT in light of the Regulation 6 Notice to the public about the Regulation 7 C. Variants 8 The Nine Families 8 Variants 9 D. Bore diameter and muzzle energy limit 12 Measurement of bore diameter: 12 The parts of a firearm 13 The measurement of bore diameter for shotguns 15 The measurement of bore diameter for rifles 19 Muzzle Energy 21 E. Non-prohibited firearms currently available for hunting and shooting 25 Hunting 25 Sport shooting 27 F. Examples of firearms used in mass shooting events in Canada that are prohibited by the Regulation 29 2 I, Murray Smith, of Ottawa, Ontario, do affirm THAT: A. Background 1. I am a forensic scientist with 42 years of experience in relation to firearms. 2. I was employed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (“RCMP”) during the period of 1977 to 2020. I held many positions during that time, including the following: a. from 1989 to 2002,1 held the position of Chief Scientist responsible for the technical policy and quality assurance of the RCMP forensic firearms service, and the provision of technical advice to the government and police policy centres on firearms and other weapons; and b. -

Fm 3-90.12/Mcwp 3-17.1 (Fm 90-13) Combined Arms Gap

FM 3-90.12/MCWP 3-17.1 (FM 90-13) COMBINED ARMS GAP-CROSSING OPERATIONS July 2008 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION. Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online <www.us.army.mil> and the General Dennis J. Reimer Training and Doctrine Digital Library at <www.train.army.mil>. *FM 3-90.12/MCWP 3-17.1 (FM 90-13) Field Manual No. Headquarters 3-90.12/MCWP 3-17.1 (FM 90-13) Department of the Army Washington, DC, 1 July 2008 COMBINED ARMS GAP-CROSSING OPERATIONS Contents Page PREFACE ............................................................................................................vii INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................x Chapter 1 OPERATIONS IN SUPPORT OF GAP CROSSING ......................................... 1-1 Challenge to Maneuver ...................................................................................... 1-1 Integrating Assured Mobility ............................................................................... 1-2 Gap-Crossing Operations................................................................................... 1-4 Chapter 2 OVERVIEW OF GAP-CROSSING OPERATIONS............................................ 2-1 Gap Crossing as a Functional Area of Mobility Operations ............................... 2-1 Gap-Crossing Means ......................................................................................... 2-4 Gap-Crossing Fundamentals ............................................................................ -

The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs

Jeremy Stöhs ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Jeremy Stöhs is the Deputy Director of the Austrian Center for Intelligence, Propaganda and Security Studies (ACIPSS) and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Institute for Security Policy, HOW HIGH? Kiel University. His research focuses on U.S. and European defence policy, maritime strategy and security, as well as public THE FUTURE OF security and safety. EUROPEAN NAVAL POWER AND THE HIGH-END CHALLENGE ISBN 978875745035-4 DJØF PUBLISHING IN COOPERATION WITH 9 788757 450354 CENTRE FOR MILITARY STUDIES How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Djøf Publishing In cooperation with Centre for Military Studies 2021 Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge © 2021 by Djøf Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior written permission of the Publisher. This publication is peer reviewed according to the standards set by the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science. Cover: Morten Lehmkuhl Print: Ecograf Printed in Denmark 2021 ISBN 978-87-574-5035-4 Djøf Publishing Gothersgade 137 1123 København K Telefon: 39 13 55 00 e-mail: [email protected] www. djoef-forlag.dk Editors’ preface The publications of this series present new research on defence and se- curity policy of relevance to Danish and international decision-makers. -

American Naval Policy, Strategy, Plans and Operations in the Second Decade of the Twenty- First Century Peter M

American Naval Policy, Strategy, Plans and Operations in the Second Decade of the Twenty- first Century Peter M. Swartz January 2017 Select a caveat DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. CNA’s Occasional Paper series is published by CNA, but the opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of CNA or the Department of the Navy. Distribution DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. PUBLIC RELEASE. 1/31/2017 Other requests for this document shall be referred to CNA Document Center at [email protected]. Photography Credit: A SM-6 Dual I fired from USS John Paul Jones (DDG 53) during a Dec. 14, 2016 MDA BMD test. MDA Photo. Approved by: January 2017 Eric V. Thompson, Director Center for Strategic Studies This work was performed under Federal Government Contract No. N00014-16-D-5003. Copyright © 2017 CNA Abstract This paper provides a brief overview of U.S. Navy policy, strategy, plans and operations. It discusses some basic fundamentals and the Navy’s three major operational activities: peacetime engagement, crisis response, and wartime combat. It concludes with a general discussion of U.S. naval forces. It was originally written as a contribution to an international conference on maritime strategy and security, and originally published as a chapter in a Routledge handbook in 2015. The author is a longtime contributor to, advisor on, and observer of US Navy strategy and policy, and the paper represents his personal but well-informed views. The paper was written while the Navy (and Marine Corps and Coast Guard) were revising their tri- service strategy document A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, finally signed and published in March 2015, and includes suggestions made by the author to the drafters during that time. -

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Netherlands Armed Forces a Strategic Survey

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Europe View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. -

Reference Sheet

TACTICALL NAVY REFERENCES Internal Communication External Communication TactiCall gives you complete control and fast access to all net- TactiCall is a perfect match for Task- or coalition force operations, works on board your vessel. Be it Functional Nets including teleph- including other military arms. SOF teams, air force, marine detach- ony, public address, entertainment systems and the like or Fighting ments and even civil and NGO agencies can be important players Nets handling alarms, broadcasts and orders, weapon teams or in the operation. More often than not, this setup includes a multi- mission control. tude of different frequency bands, networks and radio equipment. TactiCall will integrate all these into one simple and easy to use TactiCall is highly flexible and scalable, it is platform independent solution that permits everybody to reach each other regardless of and will integrate seamlessly into your combat management sys- equipment and technology used. tem of choice. In other words TactiCall lets you control all internal communication on board your vessel and with features such as TactiCall will allow key features for modern day operations like red/ record and playback helps you log and later analyze your commu- black separation, multi-level security operations, global public ad- nication flows. dress and allowing government or task force commanders to com- municate directly with whoever needs to be addressed in a given situation - facilitating a much smoother and more rapid “Statement of No Objections” chain. Contact Porten -

The Readiness of Canada's Naval Forces Report of the Standing

The Readiness of Canada's Naval Forces Report of the Standing Committee on National Defence Stephen Fuhr Chair June 2017 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. For greater certainty, this permission does not affect the prohibition against impeaching or questioning the proceedings of the House of Commons in courts or otherwise. The House of Commons retains the right and privilege to find users in contempt of Parliament if a reproduction or use is not in accordance with this permission. -

Enabling Cost-Effective Maritime Security

Coast Guard Focus Day: 29th September - Morning Non-Lethal Weapons Workshop: 29th September - Afternoon Main Conference: 30th September -1st October Location: Rome, Italy CELEBRATING A DECADE OF EXCELLENCE THE 10TH Annual International CONFERENCE HOSTED IN ROME, ITALY ENABLING COST-EFFECTIVE MARITIME SECURITY Admiral José A. Sierra Vice Admiral UO Jibrin Rear Admiral Rear Admiral Rear Admiral Rodríguez Chief of Staff Antonio Natale Geoffrey M Biekro Hasan ÜSTEM/Senior Director General of Naval Nigerian Navy Head of VII Dept., Ships Chief of Naval Staff representative Construction Design & Combat System Ghanaian Navy Commandant Mexican Italian Navy Turkish Coast Guard Secretariat of the Navy General Staff Attend the world’s largest event for the OPV Two pre-conference events: community and: * Half day of presentations focused on • Improve your technical understanding of the latest Coast Guard effectiveness with a particular OPV designs from both public and private sector shipyards to keep innovative and ahead of the market emphasis on Mediterranean Security • Benefit from strategic engagement with Admirals from navies and coastguards; understand their * Workshop examining armament options current mission sets in order to design OPVs for their requirements including non-lethal weaponry • Contribute ideas and solutions directly to senior officers and help shape the debate on delivering cost- More details on Page 6! effective maritime security. • Share industry and public sector lessons from recent capacity building and modernisation programmes -

The Royal Netherlands Navy's Perspective on Cooperation

The Royal Netherlands Navy’s perspective on cooperation Address by Lieutenant General Rob Verkerk, Commander of the Royal Netherlands Navy Galle Dialogue 2016 Abstract The fairy tale of the Bremen Town Musicians by the Brothers Grimm teaches us that change and seeking new paths may bring you an unexpected and better future. Furthermore it teaches us that cooperation is more than the sum of all parts and will enable you to achieve things that are out of reach as an individual. For those reasons, the Royal Netherlands Navy advocates cooperation with international partners. The Netherlands government has defined three strategic security interests: defence of the Netherlands and Allied territory, the international rule of law and economic security. All three imply international cooperation and indeed the Royal Netherlands Navy hardly operates anymore without cooperating with a variety of (international) partners. To enable these international operations and maintaining the required operational readiness, the Royal Netherlands Navy seeks participation in international exercises, preferably with an integrated international staff; train as you fight, fight as you train. Also technological developments, increasing costs, and international developments have led to close cooperation with industry and knowledge centres. The Royal Netherlands Navy has ample experience in this cooperation, leading to delivering more effect for less money. Some two decades ago further steps were taken by integrating large parts of the Belgian and Netherlands navies, thus reducing overhead and generate a larger scale of forces under unified command while retaining sovereignty. This integration includes command, maintenance, education and training and sharing infrastructure. Scientific research has derived criteria that are useful to balance ambition and realism in international cooperation. -

Royal Netherlands Navy Data Sheets

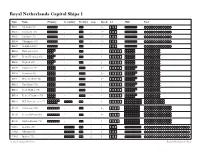

Royal Netherlands Capital Ships 1 Type Name Primary Secondary Tertiary Torp Speed AA Hull Fuel BB01 Oliphant (32) - - 1+ 4 2 1 BB02 Eendracht (32) - - 1+ 4 2 1 BB03 Kijkduin (32) - - 1+ 4 2 1 BB04 Vlissingen (32) - - 1+ 4 2 1 BB05 Gelijkheid (32) - - 1+ 4 2 1 BB06 Wassenaer (62) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB07 B. van Treslong (62) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB08 Vrijheid (62) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB09 Koopman (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB10 Evertsen (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB11 Witte de With (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB12 Van Ghent (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB13 Tjerk Hiddes (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB14 Reiner Claeszen (70) - - 2+ 8 5 3 2 1 BB15 D.Z. Provencien (117) - 3 8 5 3 2 1 BC04 Floriszoon (90) - - 3+ 6 4 2 1 BC05 R. van Holland (90) - - 3+ 6 4 2 1 BC06 Gulden Phenix (90) - - 3+ 6 4 2 1 CA01 Aemilia (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 CA02 Alkmaar (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 CA03 Jupiter (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 © 2015 Avalanche Press Royal Netherlands Navy Royal Netherlands Capital Ships 2 Type Name Primary Secondary Tertiary Torp Speed AA Hull Fuel CA04 Vergulde Haan (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 CA05 Jaarsveld (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 CA06 Neptunis (33) - 2 3 4 2 1 CA07 De Kock (20) - 2 3 3 1 CA08 van Heutsz (20) - 2 3 3 1 CA09 J.P. -

NAVAL FORCES USING THORDON SEAWATER LUBRICATED PROPELLER SHAFT BEARINGS September 7, 2021

NAVAL AND COAST GUARD REFERENCES NAVAL FORCES USING THORDON SEAWATER LUBRICATED PROPELLER SHAFT BEARINGS September 7, 2021 ZERO POLLUTION | HIGH PERFORMANCE | BEARING & SEAL SYSTEMS RECENT ORDERS Algerian National Navy 4 Patrol Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 Argentine Navy 3 Gowind Class Offshore Patrol Ships Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2022-2027 Royal Australian Navy 12 Arafura Class Offshore Patrol Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2027 Royal Australian Navy 2 Supply Class Auxiliary Oiler Replenishment (AOR) Ships Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 Government of Australia 1 Research Survey Icebreaker Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 COMPAC SXL Seawater lubricated propeller Seawater lubricated propeller shaft shaft bearings for blue water bearings & grease free rudder bearings LEGEND 2 | THORDON Seawater Lubricated Propeller Shaft Bearings RECENT ORDERS Canadian Coast Guard 1 Fishery Research Ship Thordon SXL Bearings 2020 Canadian Navy 6 Harry DeWolf Class Arctic/Offshore Patrol Ships (AOPS) Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020-2022 Egyptian Navy 4 MEKO A-200 Frigates Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2024 French Navy 4 Bâtiments Ravitailleurs de Force (BRF) – Replenishment Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2027 French Navy 1 Classe La Confiance Offshore Patrol Vessel (OPV) Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 French Navy 1 Socarenam 53 Custom Patrol Vessel Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2019 THORDON Seawater Lubricated Propeller Shaft Bearings | 3 RECENT ORDERS German Navy 4 F125 Baden-Württemberg Class Frigates Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2019-2021 German Navy 5 K130