Animal Research: a Review of Developments, 1950–2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Animal Law Received Generous Support from the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Michigan State University College of Law

JOURNAL OF ANIMAL LAW Michigan State University College of Law APRIL 2009 Volume V J O U R N A L O F A N I M A L L A W Vol. V 2009 EDITORIAL BOARD 2008-2009 Editor-in-Chief ANN A BA UMGR A S Managing Editor JENNIFER BUNKER Articles Editor RA CHEL KRISTOL Executive Editor BRITT A NY PEET Notes & Comments Editor JA NE LI Business Editor MEREDITH SH A R P Associate Editors Tabb Y MCLA IN AKISH A TOWNSEND KA TE KUNK A MA RI A GL A NCY ERIC A ARMSTRONG Faculty Advisor DA VID FA VRE J O U R N A L O F A N I M A L L A W Vol. V 2009 Pee R RE VI E W COMMITT ee 2008-2009 TA IMIE L. BRY A NT DA VID CA SSUTO DA VID FA VRE , CH A IR RE B ECC A J. HUSS PETER SA NKOFF STEVEN M. WISE The Journal of Animal Law received generous support from the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Michigan State University College of Law. Without their generous support, the Journal would not have been able to publish and host its second speaker series. The Journal also is funded by subscription revenues. Subscription requests and article submissions may be sent to: Professor Favre, Journal of Animal Law, Michigan State University College of Law, 368 Law College Building, East Lansing MI 48824. The Journal of Animal Law is published annually by law students at ABA accredited law schools. Membership is open to any law student attending an ABA accredited law college. -

Consumer Power for Animals COVER STORY

A PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN ANTI-VIVISECTION SOCIETY 2010 | Number 2 AVmagazine Consumer Power COVER STORY for Animals PRODUCT TESTING: BEGINNING TO AN END? pg 4 2010 Number 2 Consumer Power for Animals 8 FEATURES PRODUCT TESTING: 4Beginning to an End? Where we’ve been. Where we are. Where we’re going. 16 By Crystal Schaeffer 8 The Leaping Bunny Program While other compassionate shopping lists exist, only the Leaping Bunny can assure certified companies are truly cruelty-free. By Vicki Katrinak 12 What’s Cruelty-Free? Reading labels can be difficult, but looking for the Leaping Bunny Logo is easy. By Vicki Katrinak DEPARTMENTS 14 Tom’s of Maine: A Brush Above the Rest Putting ideals into action, Tom’s challenged FDA, and in a precedent-setting decision, 1 First Word was permitted to use a non-animal alternative to test its fluoride toothpaste. Consumers can and do make a difference for animals. 16 Reducing Animal Testing Alternatives development is making great strides, especially in the areas of skin and eye 2 News safety testing. Update on Great Apes; Congress Acts to By Rodger Curren Crush Cruel Videos; Bias in Animal Studies. 24 AAVS Action 20 Product Testing: The Struggle in Europe Animal testing bans mean progress, but not paradise, in Europe. $30,000 awarded for education alternatives; Humane Student and Educator Awards; and By Michelle Thew Leaping Bunny’s high standards. 22 Laws and Animal Testing 26 Giving PRESIDENT’S REPORT: An interview with Sue Leary points out the influences that For now and into the future, supporting can help—or harm—animals. -

Isa Does It the Vegan Cooking Queen Reigns Again

Living passionate Com CThe Mag of MFA. LWinter 2013 ISA DOES IT THE VEGAN COOKING QUEEN REIGNS AGAIN FOIE GRAS FOES MFA’S UNDERCOVER AGENT EXPOSES THE DELICACY’S DARK SIDE WICKED WALMART + JANE INSIDE LOOK AT THE MEGA RETAILER’S PORK SUPPLIERS VELEZ-MITCHELL MEDIA MAVEN ON A MISSION SIMON SAYS TO PROTECT ANIMALS HOLLYWOOD HEAVYWEIGHT TALKS AG-GAG, VEGANISM, AND THE FUTURE producers have shown time and time again, the answer is “a lot.” From sick animals suffering from NEWS bloody open wounds and infections, to workers WATCH viciously beating animals—every time we point our cameras at a factory farm or slaughterhouse, we find appalling abuses. Compassionate Living For over a decade, the work of MFA’s brave VEGANISM: investigators has led to landmark corporate THE FOUNTAIN OF YOUTH animal welfare policy reforms, new and improved Randyproducers Spronk have is theshown president time and of time the again, the And while Americans shouldn’t hold their ContributorsCL 1 4 Dear Friends, laws to protect farmed animals and the Veganism Nationalanswer isPork “a lot.”Producers From sick Council—a animals suffering front frombreath for people like Mr. Spronk to make environment, felony convictions of animal abusers, Vandhana BalaNEWSWATCH bloody open wounds and infections, to workers Hollywood celebrities, from Portia de Rossi to GOES group for factoryIt’s been farmers said that acrosssocial justice the movementscountry. change,increased they consumer should protectionexpect more and food from safety Amy Bradley VIRAL viciously beating animals—every time we point Alicia Silverstone, credit their plant-based diets Mr. Spronk spendsgo through most four distinctof his stagestime pimpingbefore gaining corporationsinitiatives, and that the have closure the of particularlypower, and corrupt ethical Eddie Garza our cameraswidespread at a factory acceptance: farm or first slaughterhouse, they ignore you, facilities. -

Two Fundamental Problems of Ethics

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford Ox2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York Translation, Note on the Text and Translation, Select Bibliography, Chronology, Explanatory Notes © David E. Cartwright and Edward E. Erdmann 2010 Introduction © Christopher Janaway 2010 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published as an Oxford World’s Classics paperback 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above -

Different Perspectives on Animal Rights Melissa L

DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES ON ANIMAL RIGHTS MELISSA L. LYONS DEPARTMENT OF IDS MADONNA UNIVERSITY Sponsored by EDIE WOODS([email protected]) ABSTRACT This paper will address the issue of animal rights from the perspective of six different disciplines, including biology, ethics, history, law, physiological psychology and religion. Each of these disciplines’ attempts to address questions relating to animal rights will be presented. Then, using an interdisciplinary approach, the information will be integrated in an attempt to generate new answers to questions about animal rights. INTRODUCTION Just as there are millions of animals on our planet, there are millions of views and opinions regarding animal rights. Ask a doctor his feelings regarding this subject and you may get a different answer than if you asked a priest or a lawyer. Ask someone living in America their views on animal rights and you may get a different answer than if you asked someone living in India. Animal rights are a debate that is steeped in controversy because it touches every aspect of society. The implications go beyond most imaginations. Today animals are afforded certain protections under the law. These protections include food, water and a safe environment in which to live free from undue pain and suffering. Many would like to see these animal protections taken further by giving animals their own rights, rights that may include the ability to sue in a court of law, or the right to not undergo medical procedures for animal experimentation. Giving animals rights is controversial because it would require society to stop using and treating animals in certain ways. -

The Growing Disparity in Protection Between Companion Animals and Agricultural Animals Elizabeth Ann Overcash

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 90 | Number 3 Article 7 3-1-2012 Unwarranted Discrepancies in the Advancement of Animal Law:? The Growing Disparity in Protection between Companion Animals and Agricultural Animals Elizabeth Ann Overcash Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth A. Overcash, Unwarranted Discrepancies in the Advancement of Animal Law:? The Growing Disparity in Protection between Companion Animals and Agricultural Animals, 90 N.C. L. Rev. 837 (2012). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol90/iss3/7 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNWARRANTED DISCREPANCIES IN THE ADVANCEMENT OF ANIMAL LAW: THE GROWING DISPARITY IN PROTECTION BETWEEN COMPANION ANIMALS AND AGRICULTURAL ANIMALS* INTRO D U CT IO N ....................................................................................... 837 I. SU SIE'S LA W .................................................................................. 839 II. PROGRESSION OF LAWS OVER TIME ......................................... 841 A . Colonial L aw ......................................................................... 842 B . The B ergh E ra........................................................................ 846 C. Modern Cases........................................................................ -

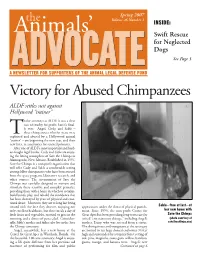

Spring 2007 Volume 26 Number 1 INSIDE: Swift Rescue for Neglected Dogs See Page 3

Spring 2007 Volume 26 Number 1 INSIDE: Swift Rescue for Neglected Dogs See Page 3 A NEWSLETTER FOR SUPPORTERS OF THE ANIMAL LEGAL DEFENSE FUND Victory for Abused Chimpanzees ALDF settles suit against Hollywood “trainer” o the attorneys at ALDF, it was a clear case of cruelty for profit, but it’s final- ly over. Angel, Cody, and Sable – three chimpanzees who for years were Texploited and abused by a Hollywood animal “trainer” – are beginning the new year, and their new lives, in sanctuaries for rescued primates. After one of ALDF’s most important and hard- est-fought legal battles, Cody and Sable are enjoy- ing the loving atmosphere of Save the Chimps in Alamogordo, New Mexico. Established in 1997, Save the Chimps is a non-profit organization that will offer Cody and Sable a comfortable setting among fellow chimpanzees who have been rescued from the space program, laboratory research, and other sources. The environment of Save the Chimps was carefully designed to nurture and stimulate these sensitive and complex primates, providing them with a home in which to socialize, build bonds, play, and rebuild the confidence that has been destroyed by years of physical and emo- tional abuse. Moreover, they are at long last being treated with the love they deserve, enjoying not appearances under the threat of physical punish- Sable—free at last—at only excellent healthcare, but three meals a day of ment. Since 1993, the non-profit Center for her new home with fresh fruits and vegetables, oatmeal or grits in the Great Apes has been providing long-term care for Save the Chimps morning, and a dinner of pasta salad. -

May 4, 2020 Honourable Bill Morneau Honourable Marie

May 4, 2020 Honourable Bill Morneau Honourable Marie-Claude Bibeau Minister of Finance Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food 90 Elgin St. 1341 Baseline Road Tower 7, Floor 9, Room 149 Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0G5 Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C5 Dear Ministers, Re: Animal agriculture industry requests for financial aid On behalf of Animal Justice, Mercy for Animals, and the Canadian Coalition for Farm Animals, we are writing in response to reports that the Canadian Pork Council is seeking approximately $500 million dollars in public funds to compensate for lost revenues in the pig farming industry caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Canadian Cattlemen’s Association is pushing for government programs aimed at helping the cow farming industry with the costs of feeding cows for longer periods of time and compensating producers for financial losses. Canada faces unprecedented public health challenges due to the outbreak of COVID-19. The pandemic is also taking a significant economic toll on individual Canadians, businesses, and not- for-profit groups such as ours. In the animal agriculture industry, challenges due to the COVID- 19 pandemic pose serious risks to animal welfare, including risks of staff layoffs and an inability to maintain animal care practices, confined living conditions that are even more overcrowded than they were previously, inadequate feed and veterinary supplies, animals being transported greater distances to slaughter, and animals being killed through what is known as “mass depopulation” or “culling”. Public funds should not be used to support factory farms, which are known for subjecting animals to cruelty, providing dangerous and precarious working conditions for workers, damaging the natural environment, and causing outbreaks of foodborne illnesses and viral infections. -

A Critique of Moral Vegetarianism

A CRITIQUE OF MORAL VEGETARIANISM Michael Martin Boston University EGETARIANISM is an old and respectable doctrine, and V its popularity seems to be growing.' This would be of little interest to moral philosophers except for one fact, namely that some people advocate vegetarianism on moral grounds. Indeed, two well-known moral and social philoso- phers, Robert Nozick and Peter Singer, have recently advocated not eating meat on moral grounds.2 One job of a moral philosophy should be to evaluate vegetarianism as a moral position, a position P will call moral vegetarianism. Unfortunately, there has been little critical evaluation of moral vegetarianism in the philo- sophicai iiterature. Most morai philosophers have not been concerned with the problem, and those who have, e.g., Nozick, have made little attempt to analyze and evaluate the position. As a result, important problems implicit in the moral vegetarian's position have gone unnoticed, and unsound arguments are still widely accepted. In this paper, I will critically examine moral vegetarian- ism. My examination will not be complete, of course. Some of the arguments I will present are not worked out in detail, and no detailed criticisms of any one provegetarian argument will be given. All the major provegetarian arguments I know will be critically considered, however. My examination will be divided into two parts. First, I will raise some questions that usually are not asked, let alone answered, by moral vegetarians. These questions will have the effect of forcing the moral vegetarian to come to grips with some ambiguities and unclarities in his position. Second, I will consider critically some of the major arguments given for moral vegetarianism. -

The Animals of Fukushima

The Anim als of Fukushima: One Year Later Animals of Fukushima Two Years Later: American Humane Association Impact Report “What brings me hope and peace in the year since that site visit is that American Humane Association continues to bring needed aid to the animals of Japan. ” On the one year anniversary of the stunning devastation in Fukushima, American Humane Association produced a report on our site visit to the disaster scene that included photos, facts and reflections on Japan’s Ground Zero. Thoughts of the companion animals impacted by the disaster living in temporary shelters until their families could bring them home still haunt me today. And as we have since learned, many more animals are still being rescued from the restricted area at Fukushima even today. What brings me hope and peace in the year since that site visit is that American Humane Association continues to bring needed aid to the animals of Japan. Following our site visit last year, American Humane Association committed to $130,000 in grants to the animal shelters on the ground in Fukushima. The grants were over and above the Red Star™ humane relief provisions provided directly following the disaster, demonstrating our “... many more long-term commitment to the lives of the impacted animals. animals are still Not only do we continue funding the vital work of the Fukushima shelters today, we are also working to advance community disaster preparation being rescued throughout Japan. Our Red Star™ Rescue disaster preparation tips were translated in Japanese and sent to the government prefectures throughout from the Japan. -

Compassion Or Renunciation? That Is the Question of Schopenhauer's Ethics

Enrahonar. Quaderns de Filosofia 55, 2015 51-69 Compassion or Renunciation? That is the question of Schopenhauer’s ethics Sandra Shapshay Tristan Ferrell Indiana University-Bloomington [email protected] [email protected] Reception date: 24-9-2014 Acceptance date: 23-11-2014 Abstract The traditional view of Schopenhauer’s ethical thought is to see renunciation from the will-to-life as the truest, most ethical response to a world such as ours in which suffering is tremendous, endemic, and unredeemed. In this view, Schopenhauer’s ethics of compassion, which he encapsulates in On the Basis of Morality in the principle “Harm no one; rather help everyone to the extent that you can” is a second best way of living, valuable only as a step along the path to “salvation” from the will-to-life in complete renunciation. In this paper, we suggest that this traditional picture of the ethics of compassion as ultimately a way station to the normatively preferable option of renunciation masks a fundamental conflict at the heart of Schopenhauer’s ethical thought. Instead, we argue, Schopenhauer should be interpreted as offering two independent, mutually antagonistic ethical ideals: compassion and renunciation. Bracketing Schopenhauer’s resignationism, we then pursue his ideal of compassion and offer a reconstruction of Schopenhauer’s ethics that espouses ‘degrees of inherent value’ among living beings. We aim to show that on this reconstruc- tion, Schopenhauer offers a hybrid Kantian/moral sense theory of ethics that has consider- able novelty and philosophical attractions for contemporary ethical theorizing. Keywords: Schopenhauer; ethics; pessimism; compassion; Kant. Resum. Compassió o renúncia? Aquesta és la qüestió de l’ètica de Schopenhauer La visió tradicional del pensament ètic de Schopenhauer és veure la renúncia de la volun- tat-de-viure com la resposta més vertadera i més ètica a un món com el nostre, en què el patiment és enorme, endèmic i no redimit. -

Animals Now - Strategic Action

ANIMALS NOW - STRATEGIC ACTION Animals Now (formerly Anonymous for Animal Rights) is an Israeli non-profit organization, founded in 1994, with the sole purpose of creating a better world for animals. Here is a recap of Animals Now’s activities and accomplishments in 2018. Our Vision is a world free of animal exploitation, where all living beings are treated with compassion and respect. In order to fulfill this vision, we focus on animals used for food, where the largest numbers of animals suffer. We take a multifaceted approach centered around four main areas, that reflect four different goals: Primary goals: 1. Consumer Behavior: We promote plant-based diet practical guides, such as Challenge 22, with the aim of teaching people how to reduce animal products consumption (chicken and fish in particular). 2. Policy and Welfare: We advocate for pro-animal legislation, such as banning specific cruel practices, and intercept new initiatives that would further reduce animal welfare standards. Secondary goals: 3. Attitudes and Norms: We strive to inform the public and to change prevailing attitudes towards animals in the food industry by exposing cruel practices in mass media and social media. Additionally, we aim to raise awareness of the health benefits of a plant-based diet. 4. Capacity Building and Partnerships: We are continuously expanding our number of supporters and donors, establishing relationships with influencers, collaborating with other organizations, designing training programs and building vegan challenge programs for new audiences, etc. TOOLS USED TO ACHIEVE GOALS The first two goals, Consumer Behavior and Policy and Welfare, we consider to be our primary goals, because they lead to a direct decrease in the number of animals that are harmed by the animal agriculture industries.