910300 Journal Insides#3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tennis Courts, One Large Multi‐Purpose Indoor Facility, and Over 9,000 Acres of Open Space Will Also Be Needed

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The contribution of the following individuals in preparing this document is gratefully acknowledged: City Council Robert Cashell, Mayor Pierre Hascheff, At‐Large Dan Gustin, Ward One Sharon Zadra, Ward Two Jessica Sferrazza, Ward Three Dwight Dortch, Ward Four David Aiazzi, Ward Five City of Reno Charles McNeely, City Manager Susan Schlerf, Assistant City Manager Julee Conway, Director of Parks, Recreation & Community Services John MacIntyre, Project Manager Jaime Schroeder, Senior Management Analyst Mary Beth Anderson, Interim Community Services Manager Nick Anthony, Legislative Relations Program Manager John Aramini, Recreation & Park Commissioner Angel Bachand, Program Assistant Liz Boen, Senior Management Analyst Tait Ecklund, Management Analyst James Graham, Economic Development Program Manager Napoleon Haney, Special Assistant to the City Manager Jessica Jones, Economic Development Program Manager Sven Leff, Recreation Supervisor Mark Lewis, Redevelopment Administrator Jeff Mann, Park Maintenance Manager Cadence Matijevich, Special Events Program Manager Billy Sibley, Open Space & Trails Coordinator Johnathan Skinner, Recreation Manager Suzanna Stigar, Recreation Supervisor Joe Wilson, Recreation Supervisor Terry Zeller, Park Development Planner University of Nevada, Reno Cary Groth, Athletics Director Keith Hackett, Associate Athletics Director Scott Turek, Development Director Washoe County School District Rick Harris, Deputy Superintendent 2 “The most livable of Nevada cities; City Manager’s Office the focus of culture, commerce and Charles McNeely tourism in Northern Nevada.” August 1, 2008 Dear Community Park & Recreation Advocate; Great Cities are characterized by their parks, trails and natural areas. These areas help define the public spaces; the commons where all can gather to seek solace, find adventure, experience harmony and re’create their souls. The City of Reno has actively led the community in enhancing the livability of the City over the past several years. -

Happy Tuesday and Happy New Hampshire Primary Day! the Second Test of the Presidential Race Begins This Morning and Tonight We'll See Who the Granite State Favors

February 10, 2016 Happy Tuesday And happy New Hampshire primary day! The second test of the presidential race begins this morning and tonight we'll see who the Granite State favors. Political insiders say they believe Sen. Bernie Sanders will top Hillary Clinton -- the polls favor him strongly -- while Donald Trump will get his first win after his Iowa loss. [Politico] Topping the news: Senate President Wayne Niederhauser weighed in on the LDS Church's opposition to Sen. Mark Madsen's medical marijuana bill. [Trib] [DNews][Fox13] [APviaKUTV] -> Carolyn Tuft, a victim of the Trolley Square shooting, pleaded with Utah Lawmakers to expand Medicaid. [Trib] [DNews] -> Some 65 percent of Utahns like the job that Sen. Mike Lee is doing while 59 percent say the same thing about Sen. Orrin Hatch. [UtahPolicy] Tweets of the day: From @JPFrenie: "Hey guys isn't it pretty cool that for once a Republican had a gaffe and it wasn't a sexist, corrupt or terrible thing to say. " From @RyanLizza: "Best detail I've heard from the Sanders campaign trail : one of his two press buses is nut-free" Happy Birthday: To Dave Hultgren. Tune in: On Tuesday at 12:15 p.m., Rep. Mike Noel joins Jennifer Napier-Pearce to discuss his plan to manage federal lands and other developments in the public lands debate. Watch Trib Talk on sltrib.com. You can also join the discussion by sending questions and comments to the hashtag #TribTalk on Twitter or texting 801-609-8059. From Capitol Hill : The Senate passed a proposal to ship $40 million to charter schools, despite objections that it would cut too much out of the public education fund. -

Mass Murder and Spree Murder

Two Mass Murder and Spree Murder Two Types of Multicides A convicted killer recently paroled from prison in Tennessee has been charged with the murder of six people, including his brother, Cecil Dotson, three other adults, and two children. The police have arrested Jessie Dotson, age 33. The killings, which occurred in Memphis, Tennessee, occurred in February 2008. There is no reason known at this time for the murders. (Courier-Journal, March 9, 2008, p. A-3) A young teenager’s boyfriend killed her mother and two brothers, ages 8 and 13. Arraigned on murder charges in Texas were the girl, a juvenile, her 19-year-old boyfriend, Charlie James Wilkinson, and two others on three charges of capital murder. The girl’s father was shot five times but survived. The reason for the murders? The parents did not want their daughter dating Wilkinson. (Wolfson, 2008) Introduction There is a great deal of misunderstanding about the three types of multi- cide: serial murder, mass murder, and spree murder. This chapter will list the traits and characteristics of these three types of killers, as well as the traits and characteristics of the killings themselves. 15 16 SERIAL MURDER Recently, a school shooting occurred in Colorado. Various news outlets erroneously reported the shooting as a spree killing. Last year in Nevada, a man entered a courtroom and killed three people. This, too, was erro- neously reported as a spree killing. Both should have been labeled instead as mass murder. The assigned labels by the media have little to do with motivations and anticipated gains in the original effort to label it some type of multicide. -

Mother Jones Mass Shootings Database

Mother Jones - Mass Shootings Database, 1982 - 2019 - Sheet1 case location date summary fatalities injured total_victims location age_of_shooter Dayton entertainment district shooting Dayton, OH 8/4/19 Connor Betts, 24, died during the attack, following a swift police response. He wore tactical gear including body armor and hearing protection, and had an ammunition device capable of holding 100 rounds. Betts had a history of threatening9 behavior27 dating 36backOther to high school, including reportedly24 having hit lists targeting classmates for rape and murder. El Paso Walmart mass shooting El Paso, TX 8/3/19 Patrick Crusius, 21, who was apprehended by police, posted a so-called manifesto online shortly before the attack espousing ideas of violent white nationalism and hatred of immigrants. "This attack is a response to the Hispanic invasion22 of Texas,"26 he allegedly48 Workplacewrote in the document. 21 Gilroy garlic festival shooting Gilroy, CA 7/28/19 Santino William LeGan, 19, fired indiscriminately into the crowd near a concert stage at the festival. He used an AK-47-style rifle, purchased legally in Nevada three weeks earlier. After apparently pausing to reload, he fired additional multiple3 rounds12 before police15 Other shot him and then he killed19 himself. A witness described overhearing someone shout at LeGan, "Why are you doing this?" LeGan, who wore camouflage and tactical gear, replied: “Because I'm really angry." The murdered victims included a 13-year-old girl, a man in his 20s, and six-year-old Stephen Romero. Virginia Beach municipal building shooting Virginia Beach, VA 5/31/19 DeWayne Craddock, 40, a municipal city worker wielding handguns, a suppressor and high-capacity magazines, killed en masse inside a Virginia Beach muncipal building late in the day on a Friday, before dying in a prolonged gun battle12 with police.4 Craddock16 reportedlyWorkplace had submitted his40 resignation from his job that morning. -

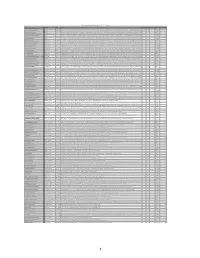

Media Mentions 12/20/2010 December 20, 2010

Media Mentions 12/20/2010 December 20, 2010 Media Mentions 12/20/2010 Project # of Articles Print Online Soc. Media B'cast Newswires 2010 Hits 40 10 25 2 0 3 Project: 2010 Hits Type Date Headline City State Prominence Tone Publication / Journalist 12/20/2010 Shooting survivor fulfills his non-mission LDS â??missionâ?? Salt Lake Tribune Salt Lake City UT 1 12/20/2010 Loss of uncle inspired, motivated Boise StateÂ?s Jeron Johnson Idaho Statesman Boise ID 1 CHADD CRIPE 12/20/2010 Box Elder commissioners endorse USU-Brigham City expansion Cache Valley Daily n/a n/a 2 12/20/2010 Joint vet program at USU approved Deseret Morning News Salt Lake City UT 3 Amy Joi O'Donoghue, Deseret News 12/20/2010 Utah universities hang on as nationwide contributions decline Deseret Morning News Salt Lake City UT 2 Michael De Groote, Deseret News 12/20/2010 Cycling The Spirit Of Giving Herald Journal n/a UT 2 n/a 12/20/2010 Logan Woman Decks The Halls Year-Round Herald Journal n/a UT 1 n/a 12/19/2010 Trolley Square survivor brings hope to children of Africa Salt Lake Tribune Salt Lake City UT 1 12/19/2010 Men’s basketball pulls out win in final minute of play Western Herald n/a n/a 1 kmurphy 12/19/2010 Teacher departs in her favorite season ; Family remembers upbeat approach Concord Monitor (NH) Concord NH 1 Ray Duckler; Monitor staff 12/19/2010 Lifting Africa, one swing set at a time Salt Lake Tribune Salt Lake City UT 1 Jeremiah Stettler 12/19/2010 The Care of a Blue Spruce Tree EHow.com National n/a 1 12/19/2010 No headline - Local_briefs San Angelo Standard-Times San Angelo TX 1 12/19/2010 Peace Corps Welcomes 26 New University Partners to its Masterâ??s International Program Peace Corps n/a n/a 1 12/19/2010 SUU embarks on goals St. -

'Don't Ask, Don't Tell' Repealed

UTAH’S INDEPENDENT VOICE SINCE 1871 DEC. 19, 2010010 « SUNSUNDAYDAY » SLTRIB.COM New Mexico Bowl • Cougs roar > S11 UTES NEXT BYU WINS Las Vegas Bowl • Special section > C1 ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell’ repealed Senate • Vote ends ban on gay military members forced thousandS of AmericanS from the military and caused The U.S. Senate on Saturday: serving openly; Dream Act fails to make it to floor. others to keep secret their sex- ual orientation. Struck down the ban on openly gay men and By CARL HULSE military and also blocked the By a vote of 65-31, with eight lesbians from serving in the military. Utahns’ re- and JULIA PRESTON Dream Act, which would have RepublicanS joining Democrats, actions > A16 The New York Times granted legal status to hundredS the Senate approved and sent Blocked efforts to pass the Dream Act, which of thousandS of undocumented to President Barack Obama a would grant legal status to undocumented im- Washington • The Senate immigrant students. repeal of the Clinton-era law migrant students. Utahns’ reactions > A16 on Saturday struck down the The vote on gay service mem- known as “don’t ask, don’t tell,” Sen. Bob Sen. Orrin Pentagon ban on gay men and bers brings to a close a 17-year- a policy criticS said amounted to Bennett • Hatch • R-Utah Beat back a Republican effort to block approval lesbians serving openly in the old struggle over a policy that Please see SENATE, A16 R-Utah of a new arms control treaty with Russia. > A3 Heavy snow halts travel across Europe World • Blizzards ’ and freezing tem- A.J. -

Curriculum Vitae Name: Mary Debernard Burbank Rank: Professor, Career Line Appointed: August, 1994

Curriculum Vitae Name: Mary DeBernard Burbank Rank: Professor, Career Line Appointed: August, 1994 I. Educational History M.Ed. Washington State University- Educational Psychology, 1994 - Assessment and Special Populations B.S. University of Utah - Special Education - Behavior Disorders, 1987 B.S. University of Utah, Psychology, 1986 Credentials Washington State Teaching Certificate, 1991 North Carolina State Teaching Certificate, 1989 Utah State Teaching Certificate, 1987 Academic Honors Phi Beta Kappa Magna Cum Laude Phi Kappa Phi Phi Eta Sigma Psi Chi Golden Key National Honor Society Professional Affiliations American Educational Research Association Division K of the American Educational Research Association American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Phi Delta Kappa II. Professional Experience Assistant Dean for Teacher Education, College of Education, 2014-present Professor, Career Line, University of Utah, 2013 - present Professor, Clinical, University of Utah, 2012-present Associate Professor, Clinical University of Utah, 2007-2012 Director of the Urban Institute for Teacher Education, University of Utah, 2009-present Director of Secondary Education, University of Utah, 2007-2009. Clinical Instructor, University of Utah, Department of Teaching and Learning, 1994-2007. Coordinator of Secondary Education, University of Utah Department of Teaching and Learning 2002-2006. NCATE/USOE Program Evaluation Co-Director, University of Utah, Department of Teaching and Learning, 2001-2005. Program Evaluator, MSP Grants – Salt Lake City School District – 2006-2009. Program Evaluator, Salt Lake City School District, Utah State Office of Education, EAST-WEST science education grant, 2007-2008. Program Evaluator, MSP Grant – Jordan School District – Department of Mathematics 2009-2010. Director of Program Evaluation, University of Utah, Department of Teaching and Learning 1996-2006. -

Tactical Emergency Medical Service in Salt Lake City As Provided by the Salt Lake City Fire Department

Tactical Emergency Medical Service 1 Tactical Emergency Medical Service in Salt Lake City as Provided by the Salt Lake City Fire Department Karl Lieb Salt Lake City Fire Department Salt Lake City, Utah Tactical Emergency Medical Service 2 CERTIFICATION STATEMENT I hereby certify that this paper constitutes my own product, that where the language of others is set forth, quotation marks so indicate, and that appropriate credit is given where I have used the language, ideas, expressions, or writings of another. Signed: Tactical Emergency Medical Service 3 ABSTRACT The integration of Tactical Emergency Medical Services into law enforcement special operations is becoming more common throughout this country. These personnel are often drawn from fire department ranks given their common public safety responsibility, their training in emergency medicine, and their experience in providing emergency care in various environments. Such programs allow emergency medical responders prompt access to patients who may be in need of immediate medical intervention. The Salt Lake City Fire Department currently has no established program to provide tactically trained emergency medical personnel (EMS) to SWAT members, patrol officers, or members of the public in SWAT or active shooting incidents. In the interest of public safety, Salt Lake City Fire Department needs to provide trained tactical medical personnel as an integral element to any Salt Lake City Police Department tactical operation. The purpose of the following research was to identify and provide both Salt Lake City Police and Salt Lake City Fire with a practical means to provide tactical EMS service to police department operations during these types of responses. -

Vol. 08 No. 3 Religious Educator

Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel Volume 8 Number 3 Article 34 9-1-2007 Vol. 08 No. 3 Religious Educator Religious Educator Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Educator, Religious. "Vol. 08 No. 3 Religious Educator." Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 8, no. 3 (2007). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol8/iss3/34 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THe Re Thoughts on the Trolley L Square Shootings igi iNside THis ISSUE: O us The Power of Student Discovery and Sharing e duca The Dead Sea Scrolls in a Latter-day Context a Historian by Yearning: a conversation with elder Marlin K. Jensen TOR Elder Marlin K. Jensen and David F. Boone • Pe VOL 8 NO 3 • 2007 R The creation: an introduction to Our Relationship to god s P Michael A. Goodman ec T i V es Night of Blood and Horror: Thoughts on the Trolley square shootings Elder Alexander B. Morrison ON TH A Historian by Yearning e Res Old Testament Relevancy Reaffirmed by Restoration scripture Scott C. Esplin TOR Conversation with Elder Marlin K. Jensen ed Teaching Old Testament Laws gO Lauren Ellison s P e L Promoting Peculiarity: different editions of For the Strength of Youth RELIGIOUS STUDIES CENTER • BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY Brent D. -

Mass Shootings in the United States: an Exploratory Study of the Trends

Mass Shootings in the United States: An Exploratory Study of the Trends from 1982- 2012 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Luke Dillon Bachelor of Science Kutztown University, 2010 Chairman: Christopher Koper, Associate Professor Department of Criminology, Law and Society Fall Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2013 Luke J. Dillon ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my loving fiancé Abby, my two amazingly supportive parents Jim and Sandy, and my dogs Moxie and Griffin who are always helpful distractions. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express gratitude to my thesis chair, Dr. Christopher Koper, for serving as a helpful mentor and providing me with his wealth of experience towards this topic. I am also deeply grateful to my thesis committee members, Dr. Cynthia Lum and Dr. James Willis who provided keen insights into turning a rough work into a finely tuned project. Their assistance through being a committee member, but even more significantly, a teacher has helped me grow as a scholar. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables .................................................................................................................... vii List of Figures .................................................................................................................. viii Abstract .............................................................................................................................. ix Introduction -

On February 12, 2007, Salt Lake City Experienced One of the Worst Murder Incidents in the History of the City. Eighteen Year Ol

On February 12, 2007, Salt Lake City experienced one of the worst murder incidents in the history of the City. Eighteen year old Sulejmen Talovic fatally shot five victims and seriously wounded four others in a shooting spree at the Trolley Square Mall. Sulejmen Talovic was shot and killed by responding police officers. The nature of this crime and the apparent lack of motive or pre-existing connection between the victims and Talovic evoked fear, outrage, grief and anger throughout not only the City of Salt Lake, but throughout our entire nation. Law enforcement officials both locally and nationally obtained a great deal of investigative evidence through extensive interviews with victims, witnesses and family members. Surprisingly law enforcement was able to learn relatively little about Sulejmen Talovic and his motive for committing these atrocities. The information that follows is a compilation of these investigative leads. It is presented to supply information as to the events of that day and the days leading up to it and to describe the scope of the investigation in an attempt to bring about a conclusion and closure for all involved. We ask all readers of this document to respect the privacy of all those involved, especially the victims of this horrible crime, their families and the family of Sulejmen Talovic. During the immediate response to Trolley Square, numerous agencies from throughout Salt Lake County responded and played an active role in searching and securing the massive crime scene. Those agencies included the Sandy City Police Department, West Valley City Police Department, Salt Lake County Sheriff’s Office, Taylorsville Police Department, Utah Highway Patrol and US Marshall’s Office. -

Salt Lake City, Utah/November 1980

--~------ --------~. If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. NC:itional Criminal Justice Reference Service , . I,>., 1 i. I This microfiche was produced from documents received for ANT.O<II.I TEAM " • - I • I' '.' -c. 1 " ,\;., v. .. inclusion in the NCJRS data base. Since NCJRS cannot exercise control over the physical condition of the documents submitted, the individual frame quality will vary. The resolution chart on this frame may b(C! used to evaluate the document quality. ;;;1 ' 1.0 =IIIII~ "I"~ (1 w ~~~ 122. W 13.6 ::iW I~~- "I~ .......... u ""I~ 1111,1.4 '"" 1.6 \ ! MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAL DUREAU OF STANDARDS-1963-A Microfilming procedures used to create this fiche comply with .;·1 i , .. the standards set forth in 41CFR 101-11.504. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the author(s) and do not represent the official position or policies of the U. S. Department of Justice. W 4-20-81 National Institute of Justice United States Department of Justicte Washington, D. C. 20531 ---- ,_. - - ..... """~-=~,.,...::::;.;;:;:;~~ .,b,-" ,_"L_ ,"","-,~--"-~~.-,--.'-":""'~~J:....::J.,,"o-~-_==.t. .:...c.'...- ........ ,. """~ rA u. s. OEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE CATEGORICAL GRANT '"WU•• ENfORCEMEHT ASSISTANCE ADMINISTRATION PROGRESS REPORT OATE 0,. REPORT REPORT NO. G"ANTEE LEA A GRANT NO. Salt Lake City~ Utah 79-Df-AX-000.5 Jui.u· 198'!...!1"----L. __ ._11____ ._ ~1-W-P-L-E-W-E-N·-T-,NGiSUBG"ANTEII!: TYP£ OF REPORT C]REGUl.A" o SP£CIAL REQUEST 00 FINAL REPORT GRANT ,AMOUNT SHORT TITLE OF PROJECT i.84~9 -.---:----------i / THROUGH -:;;0' REPORTAnti-Crime IS SUBMIT_TEO Team FOR THE PERlor.