Notes the Fixed Easter Cycle in the Ethiopian Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Easter Around the World with Kate & Mack

Easter Around the World with Kate & Mack Hi kids! It’s me, Kate, and my friend, Mack. Easter is couple days, everyone mourned (that means just five weeks away, and we’ve been traveling they were super sad) that Jesus was dead. to learn some of the different ways people But then, three days later, Jesus rose from celebrate this holiday. We’re going to make the dead! And that’s why we can celebrate — quick stops in all parts of the world — Africa, because Jesus loved us so much that he died Americas, Asia, Europe and the Pacific. We and rose again so that one day we can live know you’re busy with school and all the with him in heaven! How amazing is that? learning you have to do every day, so this But you’ll be able to read all about that over should be a fun break for you. the next few weeks with your family. After all, When you think of Easter, what’s the first it’s really important that we understand why thing that comes to mind? Maybe it’s the Jesus died for us, and what he went through Easter bunny, because you get baskets full of so that we can be forgiven of our sins. And yummy candy. Or maybe it’s dyeing Easter there’s no better time to talk about it a lot eggs with your family. than around Easter, right? Hopefully you also think of the true reason So are you ready to travel the world with us? that we celebrate Easter! After all, it doesn’t Let’s get started! really have anything to do with bunnies or candy. -

The Seven Major Fasts in the Orthodox Tewahedo Church

The Seven Major Fasts In The Orthodox Tewahedo Church By: Tigist Lakew 1. The Fast Of Nativity/ Advent ( Tsome Nebiyat) The fast that precedes Christmas. Christmas is celebrated on January 7th. This fast is to commemorate the fast that Moses fasted in the Mount of Sinai. He fasted for 40 days before receiving the Ten Commandments which hosted the word of God in it. As a lesson from Moses, he fasted prior to Christmas for 40 days before receiving the word of God, so we do the same and fast for 40 days before receiving the word of God. 2. The Fast Of Nineveh ( Tsome Nineveh) Precedes the great lent by 2 weeks. This Fast is held on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday. This Fast commemorates the fast the people living in the city of Nineveh did because the city was full of sins . God sent the prophet Jonah to the city of Nineveh , to repent and pray because their city was about to get destroyed. The King and the whole city began fasting and God heard their prayers and he forgave them. And taking that as a lesson we fast the three day fast so we can repent and be forgiven by God. 3. The Fast Of Great Lent ( Abiy Tsom) Proceeds the Fast of Nineveh. It begins on a Monday and ends on Easter ( Faskia, Abiy Tsom) Within this Fast each week is broken down into specific themes. 3. The Fast Of Great Lent First Week: Zewerede To come, mission of Christ when he came here. To give us salvation. -

Resurrection, Became Apparent Which They Escaped

anyone who would not be conquered by the Kings 13:20-21). All these people, nonetheless, did Creator and anyone whom God’s authority not abrogate our death; they did not get rid of would not defeat, the Word Incarnate Jesus death’s power. When they were raised from the Christ won victory over death and resurrected dead with the prophets’ and apostles’ prayers and on the third day. The mystery that the flesh will God’s kindness, it was to live for themselves. In be raised after death and that it will live eter- fact, they have returned to death’s bondage from nally, the hope of resurrection, became apparent which they escaped. However, our Lord and Sav- through Christ’s resurrection. Being the first to ior Jesus Christ, through His Deity and Divine be risen from the dead, He granted resurrection authority, defeated death for eternity and rose. In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, to all of us. (1 Corinthians 15:20). What cannot He made us cross over from death to life. and of the Holy Spirit, One God, Amen. be done by man was done by the One Who was manifested in the flesh. The power of death is Christ Our Passover Lamb abrogated forever by His Divine power. Saint The Israelites (also known as Israelites in the Resurrection Day Cyril says this in Haimanote Abew (a book flesh) used to observe Passover ever since their (Tinsa’e) whose title translates to Faith of the Fathers), exodus from Egypt to reminisce the bitterness of “He abolished death’s victory. -

The Liturgy of the Ethiopian Church

THE LITURGY OF THE ETHIOPIAN CHURCH Translated by the Rev. MARCOS DAOUD Revised by H. E. Blatta MARSIE HAZEN from the English/Arabic translation of Marcos Daoud & H.E. Blatta Marsie Hazen Published in March, 1959 Reprinted June 1991 by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church Kingston, Jamaica with introduction by Abuna Yesehaq Reponsability for errors in this edition is on Priest-monk Thomas Please, forward all comments, questions, suggestions, corrections, criticisms, to [email protected] Re-edited March 22, 2006 www.ethiopianorthodox.org 1 CONTENTS paragraphs total page Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 3 Consecration of New Vessels......................(CHAPTER I)......................................... 13 11 Preparatory Service..................................(CHAPTER II)........................................... 72 12 “ “ ....................................(CHAPTER III)..................................... 219 19 “ “ ...................................... (CHAPTER IV)................................... 62 38 In practice, the logical extension : “ CHAPTER V” would be one of the following anaphoras A. The Anaphora of the Apostles.................................................................................170...... 43 B. The Anaphora of the Lord ................................................................................... 84........58 C. The Anaphora of John, Son of Thunder............................................................. -

The Shade of the Divine Approaching the Sacred in an Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Community

London School of Economics and Political Science The Shade of the Divine Approaching the Sacred in an Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Community Tom Boylston A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, March 2012 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 85956 words. 2 Abstract The dissertation is a study of the religious lives of Orthodox Christians in a semi‐ rural, coffee‐producing community on the shores of Lake Tana in northwest Ethiopia. Its thesis is that mediation in Ethiopian Orthodoxy – how things, substances, and people act as go‐betweens and enable connections between people and other people, the lived environment, saints, angels, and God – is characterised by an animating tension between commensality or shared substance, on the one hand, and hierarchical principles on the other. This tension pertains to long‐standing debates in the study of Christianity about the divide between the created world and the Kingdom of Heaven. -

Oral and Written Transmission in Ethiopian Christian Chant

Oral and Written Transmission in Ethiopian Christian Chant The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Shelemay, Kay Kaufman, Peter Jeffery, and Ingrid Monson. 1993. Oral and written transmission in Ethiopian Christian chant. Early Music History 12: 55-117. Published Version http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0261127900000140 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3292407 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Oral and Written Transmission in Ethiopian Christian Chant Author(s): Kay Kaufman Shelemay, Peter Jeffery, Ingrid Monson Source: Early Music History, Vol. 12 (1993), pp. 55-117 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/853869 Accessed: 24/08/2009 21:27 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cup. -

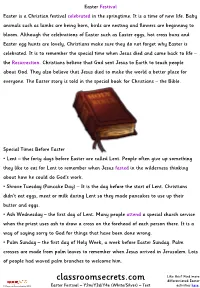

Classroomsecrets.Com Differentiated Easter © Classroom Secrets Limited 2016 Easter Festival – Y2m/Y3d/Y4e (White/Silver) – Text Activities Here

Easter Festival Easter is a Christian festival celebrated in the springtime. It is a time of new life. Baby animals such as lambs are being born, birds are nesting and flowers are beginning to bloom. Although the celebrations of Easter such as Easter eggs, hot cross buns and Easter egg hunts are lovely, Christians make sure they do not forget why Easter is celebrated. It is to remember the special time when Jesus died and came back to life – the Resurrection. Christians believe that God sent Jesus to Earth to teach people about God. They also believe that Jesus died to make the world a better place for everyone. The Easter story is told in the special book for Christians – the Bible. Special Times Before Easter • Lent – the forty days before Easter are called Lent. People often give up something they like to eat for Lent to remember when Jesus fasted in the wilderness thinking about how he could do God’s work. • Shrove Tuesday (Pancake Day) – It is the day before the start of Lent. Christians didn’t eat eggs, meat or milk during Lent so they made pancakes to use up their butter and eggs. • Ash Wednesday – the first day of Lent. Many people attend a special church service when the priest uses ash to draw a cross on the forehead of each person there. It is a way of saying sorry to God for things that have been done wrong. • Palm Sunday – the first day of Holy Week, a week before Easter Sunday. Palm crosses are made from palm leaves to remember when Jesus arrived in Jerusalem. -

Paschal Troparion

Paschal troparion From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search "Christ anesti" redirects here. For the greeting, see Paschal greeting. The Paschal troparion or Christos anesti (Greek: Χριστὸς ἀνέστη) is the characteristic hymn for the celebration of Pascha (Easter) in the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite. Like most troparia it is a brief stanza often used as a refrain between the verses of a Psalm, but is also used on its own. Its authorship is unknown. It is nominally sung in Tone Five, but often is sung in special melodies not connected with the Octoechos. It is often chanted thrice (three times in succession). [edit] Usage The troparion is first sung during the Paschal Vigil at the end of the procession around the church which takes place at the beginning of Matins. When all are gathered before the church's closed front door, the clergy and faithful take turns chanting the troparion, and then it is used as a refrain to a selection of verses from Psalms 67 and 117 (this is the Septuagint numbering; the KJV numbering is 68 and 118): Let God arise, let His enemies be scattered; let those who hate Him flee from before His face (Ps. 67:1) As smoke vanishes, so let them vanish; as wax melts before the fire (Ps. 67:2a) So the sinners will perish before the face of God; but let the righteous be glad (Ps. 67:2b) This is the day which the Lord hath made, let us rejoice and be glad in it. -

Religion, Ethnicity, and Charges of Extremism: the Dynamics of Inter -Communal Violence in Ethiopia 1

Header 01 Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nullam elementum nec ipsum et iaculis. Nunc convallis velit vel urna aliquet vehicula. Nunc eu arcu vestibulum, dignissim dui ut, convallis nibh. Integer ultricies nisl quam, quis vehicula ligula fringilla ut. Fusce blandit mattis augue vel dapibus. Aliquam magna odio, suscipit vel accumsan ut, dapibus at ipsum. Duis id metus commodo, bibendum lacus luctus, sagittis lectus. Morbi dapibus, dolor quis aliquam eleifend, diam massa finibus ex, mattis tincidunt nisi elit eu leo. Ut ornare massa dui, sit amet pharetra erat tincidunt sed. Proin consequat viverra est ac venenatis. Interdum et malesuada fames ac ante ipsum primis in faucibus. Aenean id posuere eros, eu auctor ligula. Suspendisse massa lacus, scelerisque sollicitudin dignissim mollis, tristique et arcu. Vivamus dapibus hendrerit lectus a semper. Mauris ut neque bibendum, egestas diam et, pretium orci. Phasellus a liberoRELIGION, placerat, accumsan nibh nec, ETHNICITY,pellentesque risus. Duis tempus felis AND arcu, at tincidunt urna dignissim sit amet leo. Quisque non tortor urna. Vivamus tortor orci, malesuada vel massa a, maximus vestibulumCHARGES lectus. OF EXTREMISM: THE PellentesqueDYNAMICS habitant morbi tristique senectusOF etINTER netus et malesuada-COMMUNAL fames ac turpis egestas. Sed nec lorem id dolor posuere congue. Nam sapien sapien, ullamcorper pretium blandit sed, lobortis a risus. Morbi ut sapien diam. Vivamus justo neque, suscipit non suscipit at, commodo id neque. Pellentesque nec condimentum urna. Mauris eu vestibulumVIOLENCE augue. Morbi faucibus nibh ac INmalesuada ETHIOPIA posuere. Nunc varius, sem a tincidunt ultricies, sem lectus commodo est, eget lobortis augue ex quis tellus. Vivamus at gravida tellus. Cras metus urna, feugiat ac malesuada nec, suscipit ut metus. -

Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church English Lessons for Level II

Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church English Lessons for Level II (Grades 1 ‐3) Prepared to young families of EOTC members attending their lessons at Bole Debre Salem Medhanealem Church Every Sunday between 10:00AM – 12:00 Noon Compiled by: Kesis Solomon Mulugeta Contact: +251‐911‐236767 or E‐mail: [email protected] II September: 2nd Week Creation Objective: God’s care and love for us in creation References: Genesis 1 Introduction: This is the story of God's creation. In this lesson, you are going to learn what God created in six days, and what He prepared for Adam before He made him with His own hands. The Lesson 1. In the beginning God made heaven and earth. The earth was void and there was nothing on it. There were no trees, no houses, no animals and no people. There was darkness only. And God said, “I will make a man and call him Adam. I will make him happy. He will love me and speak with me at anytime”. Then the Lord said, “I will arrange everything in the world and make the earth a good place for Adam. I will create light so that Adam can see”. 2. And then God said, “Let there be light and there was light, a bright light. Adam could see everything. He could read, play and eat. 3. When the light disappeared at night, the Lord said, “I will not leave Adam in the dark and God made the moon and the stars”. 4. Then the Lord said: “When Adam comes, what will he eat?” The Lord ordered the earth to bring out good vegetables so that when Adam comes he can eat good food. -

English Translation Of

CultureTalk Ethiopia Video Transcripts: http://langmedia.fivecolleges.edu Easter English translation: N: Nafkote M: Woman on the left M: Fasika 1 has a very special meaning to me, of all the holidays. N: Because you wake up in the middle of the night to eat? M: Not only that but also the period of fasting before it. Many Christians fast at that time, including me. You fast for two months, then Good Friday is the day for sigdet 2– the day is spent fasting and then bowing at Church. Then Saturday, at my house, is usually spent with family. N: To prepare for the holiday on Sunday. M: Yes for the holiday on Sunday. So, Saturday is spent like that, and at night, my mother usually spends the night cooking for nine hours. Even if we do not help directly, we support her by talking to her and being around her. Then we go to church at night. N: Overnight. M: Overnight. Then at 3 a.m. we get woken up and we eat chicken. N: And then the day begins. Oh, in many ways, Fasika – in Christianity, or even in the Bible – it’s a very major holiday. The resurrection of Jesus Christ is an important day. About CultureTalk: CultureTalk is produced by the Five College Center for the Study of World Languages and housed on the LangMedia Website. The project provides students of language and culture with samples of people talking about their lives in the languages they use everyday. The participants in CultureTalk interviews and discussions are of many different ages and walks of life. -

Notes the Fixed Easter Cycle in the Ethiopian Church

_full_journalsubtitle: Journal of Patrology and Critical Hagiography _full_abbrevjournaltitle: SCRI _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 1817-7530 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1817-7565 (online version) _full_issue: 1 _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (change var. to _alt_author_rh): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (change var. to _alt_arttitle_rh): The Fixed Easter Cycle in the Ethiopian Church _full_alt_articletitle_toc: 0 _full_is_advance_article: 0 The Fixed Easter Cycle InScrinium The Ethiopian 14 (2018) 463-466Church 463 www.brill.com/scri Notes ∵ The Fixed Easter Cycle in the Ethiopian Church Ekaterina V. Gusarova Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences; Manuscript Department of the National Library of Russia; National Research University Higher School of Economics (St. Petersburg) [email protected] Abstract This article deals with the fixed Christian Easter and the feasts, which depend on it. Both moveable and fixed feasts are recorded in Christian calendars and synaxaria. Following the decisions of the First Oecumenical Council of Nicaea (AD 325) the Ethiopians cele- brated mostly the moveable Easter and its cycle. At the same time in the Ethiopian Royal Chronicles is also recorded that the Ethiopian Kings and their armies celebrated the fixed Easter and its festivals, especially the Good Friday. Keywords Ethiopian Church – Alexandrian Church – Computus – Christian moveable and fixed feasts – Ethiopic calendar – fixed Easter – fixed Good Friday – Ethiopian Royal Chronicles The tradition narrates that initially the Ethiopian clergy was not capable to calculate the Easter (ፋሲካ፡fasika) because this responsibility layed within the duties of Coptic Patriarchs of Alexandria. They annually idetified the dates of the Easter Festival and announced it to other Christian churches. As a result, ©Scrinium Ekaterina 14 V.(2018) Gusarova, 463-466 2018 | doi 10.1163/18177565-00141P30 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 02:27:40PM This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC License.