Rathmichael Historical Record 1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Dublin's North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960S'

Edinburgh Research Explorer Dublin’s North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960s Citation for published version: Hanna, E 2010, 'Dublin’s North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960s', Historical Journal, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 1015-1035. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X10000464 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0018246X10000464 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Historical Journal Publisher Rights Statement: © Hanna, E. (2010). Dublin’s North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960s. Historical Journal, 53(4), 1015-1035doi: 10.1017/S0018246X10000464 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 The Historical Journal http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS Additional services for The Historical Journal: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here DUBLIN'S NORTH INNER CITY, PRESERVATIONISM, AND IRISH MODERNITY IN THE 1960S ERIKA HANNA The Historical Journal / Volume 53 / Issue 04 / December 2010, pp 1015 - 1035 DOI: 10.1017/S0018246X10000464, Published online: 03 November 2010 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0018246X10000464 How to cite this article: ERIKA HANNA (2010). -

Social Housing Construction Projects Status Report Q3 2019

Social Housing Construction Projects Status Report Q3 2019 December 2019 Rebuilding Ireland - Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness Quarter 3 of 2019: Social Housing Construction Status Report Rebuilding Ireland: Social Housing Targets Under Rebuilding Ireland, the Government has committed more than €6 billion to support the accelerated delivery of over 138,000 additional social housing homes to be delivered by end 2021. This will include 83,760 HAP homes, 3,800 RAS homes and over 50,000 new homes, broken down as follows: Build: 33,617; Acquisition: 6,830; Leasing: 10,036. It should be noted that, in the context of the review of Rebuilding Ireland and the refocussing of the social housing delivery programme to direct build, the number of newly constructed and built homes to be delivered by 2021 has increased significantly with overall delivery increasing from 47,000 new homes to over 50,000. This has also resulted in the rebalancing of delivery under the construction programme from 26,000 to 33,617 with acquisition targets moving from 11,000 to 6,830. It is positive to see in the latest Construction Status Report that 6,499 social homes are currently onsite. The delivery of these homes along with the additional 8,050 homes in the pipeline will substantially aid the continued reduction in the number of households on social housing waiting lists. These numbers continue to decline with a 5% reduction of households on the waiting lists between 2018 and 2019 and a 25% reduction since 2016. This progress has been possible due to the strong delivery under Rebuilding Ireland with 90,011 households supported up to end of Q3 2019 since Rebuilding Ireland in 2016. -

Minutes of Meeting of Dublin and Dún Laoghaire

MINUTES OF MEETING OF DUBLIN AND DÚN LAOGHAIRE EDUCATION AND TRAINING BOARD HELD ON MONDAY 21st MAY, 2018 IN ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICES, 1 TUANSGATE, BELGARD SQUARE EAST, TALLAGHT, DUBLIN, 24 Present: Cllr Sorcha Nic Cormaic, Cathaoirleach Cllr Roderic O’Gorman Cllr Mick Duff Barry Hempenstall Cllr Pat Hand Cllr Liona O’Toole Cllr Howard Mahony Cllr Eithne Loftus Cllr Ossian Smyth Gerry McGuire Dr. John Walsh Cllr. Ken Farrell Karen Gleeson Claire Markey Gerry McCaul Anne Genockey In Attendance: Paddy Lavelle, Chief Executive Officer Paul McEvoy, Director of Organisation Support & Development Martin Clohessy, Director of Organisation Support & Development Dr Fionnuala Anderson, Director of Further Education & Training Apologies: Cllr Conor McMahon Olive Phelan Cllr Grainne Maguire Paul McNally At the outset votes of sympathy was extended to the following: Deirdre Keogh, ETBI, on the death of her Father. The family of Sean Hanley, Former Principal , Deansrath Community College. Liz Lavery, Director of Schools, Longford Westmeath ETB, on the death of her husband 1. Minutes Minutes of meeting held on 20th March 2018 The minutes were confirmed and signed on the proposal of Cllr Mick Duff, seconded by Gerry McGuire. 2. Matters Arising None 3. Consideration of Reports from Committees Board of Management Minutes 3.1. Adamstown CC BoM Minutes 21st February 2018 3.2. Adamstown CC BoM Minutes 6th March 2018 3.3. Ardgillan CC BoM Minutes 24th January 2018 3.4. Ardgillan CC BoM Minutes 7th March 2018 3.5. Blackrock FEI BoM Minutes 16th January 2018 3.6. Castleknock CC BoM Minutes 30th January 2018 3.7. Castleknock CC BoM Minutes 21st February 2018 3.8. -

PDF (Dun Laoghaire

DUN LAOGHAIRE – RATHDOWN LOCAL DRUG TASK FORCE SECOND REPORT SEPTEMBER 1997 Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. The process of preparing 2nd Task Force Report 4 3. Profile of Dun Laoghaire - Rathdown Task Force Area 5 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Population Profile 3.3 Social Disadvantage 4. The nature and extent of drug problem in the Dun 8 Laoghaire/Rathdown area 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Local Survey Data 4.3 Health Statistics 4.4 Other Health Data 4.5 Probation Service 4.6 Law Enforcement Statistics 5. Outline of Current/Planned Service provision and Service 33 development proposals from the Task Force 5.1 Introduction 5.2 (i) Current Education and Prevention Provision (ii) Service development Proposals 5.3 (i) Current Treatment and Rehabilitation Provision (ii) Service Development Proposals 5.4 Supply and Estate Management 6. The role of the Task Force in implementation and 59 monitoring of the Service Development Proposals. 7. Conclusions 60 Appendices: Members of Task Force 61 Letters Requesting Submissions 62 List of Submissions Received 63 Summary of Funding Proposals 64 Members of Task Force sub-committees 65 2 SECTION 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO DUN LAOGHAIRE-RATHDOWN DRUGS TASK FORCE 2ND REPORT The Task Force was established in March 1997 to prepare a service development plan for the Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown county area including Whitechurch and parts of Rathfarnham. There was an initial expectation that Task Forces would submit plans by early summer but this was not possible for us because of time constraints. The Task Force decided therefore to prepare interim proposals pending the elaboration of a detailed report and project proposals for submission to the National Drug Strategy Team. -

Administration Jobs

Administration Jobs Job Title Location Duties/Job Description Contact Administration Rathfarnham Providing administrative support in a small Linda - Assistant organisation - reception, filing, dealing with clients 087 1364935 and members of the organisation, assisting with accounts Administration Ballyogan Providing administrative support in a small Ciara - Assistant organisation - reception, filing, dealing with clients 087 7370366 and visitors Administrator Blackrock Preparation of Daily team roster ,documenting Seamus - Client Reports and Comment book, Recording daily 087 1155030 attendances, Recording Invoices, Updating Client and Human Resources files and Supporting with requirements of Health Act, audits in data gathering and updating files Administration Cabinteely High level of office experience & admin Dave - Assistant 087 7370327 Receptionist Cabinteely Office duties, greeting visitors to the centre Dave - 087 7370327 Administrative Dun Laoghaire General Admin Work Seamus - Assistant 087 1155030 Box Office Dundrum Assist with the box office, taking bookings over the Gerarda - Assistant / phone and face to face. Also provide some admin 087 9970376 Administration support to the marketing team. Various Dundrum Admin/front office/Horticulture/Maintenance Ciara - 087 7370366 Administration Rathfarnham General Office Duties Ciara - Assistant 087 7370366 Administrator/ Sandyford Assisting with the activities of the network, Linda - Project Worker Attendance records for groups, Shopping for the 087 1364935 Groups, assisting with groups. -

The Story of a House Kevin Casey

The Story of a House Kevin Casey Everything we know about Nathaniel Clements suggests that he was an archetypal Ascendancy man. Eighteenth century Dublin was a good place in which to be young, rich and of the ruling class. The Treaty of Limerick - the event that marked the beginning of the century as definitively as the Act of Union ended it - provided a minority of the population, the Ascendancy, with status, influence and power. Penal Laws, imposed upon Roman Catholics and Dissenters, made it impossible for them to play an active part in Government or to hold an office under the Crown. Deprived of access to education and burdened with rigorous property restrictions, they lived at, or below, subsistence level, alienated from the ruling class and supporting any agitation that held hope of improving their lot. Visitors to the country were appalled by what they saw: "The poverty of the people as I passed through the country has made my heart ache", wrote Mrs. Delaney, the English wife of an Irish Dean. "I never saw greater appearance of misery." Jonathan Swift provided an even more graphic witness: "There is not an acre of land in Ireland turned to half its advantage", he wrote in 1732, "yet it is better improved than the people .... Whoever travels this country and observes the face of nature, or the faces and habits and dwellings of the natives, will hardly think himself in a land where law, religion or common humanity is professed." For someone like Nathaniel Clements, however, the century offered an amalgam of power and pleasure. -

Bulletin-4Th-December-2016

Our Lady of Victories Sallynoggin / Glenageary Phone: (01) 2854667 email: [email protected] Website: www.sallynogginandglenagearyparish.com Second Sunday of Advent, Year A, December 4th, 2016. Bulletin No: 1140. ADVENT MASS TIMES: Sunday Holy Days Celebrant 8.30am, 10am (Irish) 6.30pm (Vigil), 9am (Rejoice in the Lord always) 11.30am, 5.30pm 11.30am, 6.30pm Saturdays Monday In today’s readings we shall hear about the mission of John 9am, 6.30pm (Vigil) 9am, 6.30pm the Baptist who was sent to prepare the way for the coming Tuesday - Friday of Jesus the light of the world. We too, are sent to prepare 9am, No Evening Mass the way. As we light the second candle on the Advent wreath let us pray we may be worthy of our mission to CONFESSIONS: Saturday spread the light of Christ in the world so that all may 10.30 —11.30 a.m. acknowledge Jesus as Lord. 5.30 p.m.—6.15 p.m. BAPTISMS: At the lighting Celebrated on the First Sunday and Third Saturday of the month, arrangements having been made in person at the presbytery giving of the candle three weeks notice. EUCHARISTIC ADORATION: all pray together: Daily Chapel open from 7.30 a.m. to 10.00 p.m. Lord God, you sent your beloved Son into the world as a Divine Mercy: light that shines in the darkness. Grant that our Wednesdays from 2.45 p.m. to 3.45 p.m. Advent wreath, may be, for us, and for all who visit here, a Miraculous Medal Novena is prayed at both sign of faith, as we prepare our hearts for the coming of our Masses on Monday. -

UCD Commuting Guide

University College Dublin An Coláiste Ollscoile, Baile Átha Cliath CAMPUS COMMUTING GUIDE Belfield 2015/16 Commuting Check your by Bus (see overleaf for Belfield bus map) UCD Real Time Passenger Information Displays Route to ArrivED • N11 bus stop • Internal campus bus stops • Outside UCD James Joyce Library Campus • In UCD O’Brien Centre for Science Arriving autumn ‘15 using • Outside UCD Student Centre Increased UCD Services Public ArrivED • UCD now designated a terminus for x route buses (direct buses at peak times) • Increased services on 17, 142 and 145 routes serving the campus Transport • UCD-DART shuttle bus to Sydney Parade during term time Arriving autumn ‘15 • UCD-LUAS shuttle bus to Windy Arbour on the LUAS Green Line during Transport for Ireland term time Transport for Ireland (www.transportforireland.ie) Dublin Bus Commuter App helps you plan journeys, door-to-door, anywhere in ArrivED Ireland, using public transport and/or walking. • Download Dublin Bus Live app for updates on arriving buses Hit the Road Don’t forget UCD operates a Taxsaver Travel Pass Scheme for staff commuting by Bus, Dart, LUAS and Rail. Hit the Road (www.hittheroad.ie) shows you how to get between any two points in Dublin City, using a smart Visit www.ucd.ie/hr for details. combination of Dublin Bus, LUAS and DART routes. Commuting Commuting by Bike/on Foot by Car Improvements to UCD Cycling & Walking Facilities Parking is limited on campus and available on a first come first served basis exclusively for persons with business in UCD. Arrived All car parks are designated either permit parking or hourly paid. -

Representative Church Body Library, Dublin Ms

1 REPRESENTATIVE CHURCH BODY LIBRARY, DUBLIN MS 624 The records of the Young Women's Christian Association in Ireland (YWCA) including minute books and correspondence of the executive council, standing committee, several divisional councils and specific committees. 1885-2007 As well as general administrative material such as minutes, accounts and correspondence, the collection also includes memorabilia including leaflets, tracts, prayer cards and orders of service for special events giving colour to the organisation’s history. Topics covered include its early training home for missionaries; the national annual conference and annual sale; the development of the Dublin Bible College in the 1940s and early 1950s; and the development of camps activities for young people, boarding hostels and homes for workers throughout the island under both central and local branch control. Extensive materials also record the history of specific branches, hostels, houses and holiday homes, including Queen Mary Home, Belfast, the Baggot Street Hostel and the Radcliff Hall, Dublin, as well as the business and share- holding records of the YWCA Trust Corporation which managed YWCA properties. The collection is organised into 13 record groups, listed on pages 2 and 3 below. All of the material is open to the public with the exception of those items marked [CLOSED] for which the permission of the Board of the YWCA in Ireland, must first be obtained in writing, before access will be granted. From YWCA, Bray, deposited by Mrs Daphne Murphy, 1998; and YWCA headquarters, Dublin, 2012. 2 Arrangement 1. Minutes of the central administrative organisation (including the Executive Council, the General Council, the Irish Divisional Council, and the Standing Committee). -

A Short History of Dundrum and Gordonville

Gordonville: A Short History of Dundrum and Gordonville MICHAEL VAN TURNHOUT Introduction My wife grew up in a beautiful old house in Dundrum called Gordonville, at Sydenham Villas. It is still in the hands of her family. I wanted to know a bit more about the house and I discovered it was a symbol of a very important period in the development of Dundrum. This is its story. Note: in the article, it will also be referred to as ‘1 Sydenham Terrace’, as this was its original designation. Dundrum in the early days The name Dundrum goes back to the time of the Anglo-Norman conquest. Originally it was part of a larger estate, but one of its many owners gave part of it to the Priory of the Holy Trinity. This is now Taney. The remainder became Dundrum. An interesting footnote in history is that a later owner exchanged his Dundrum lands for land in Limerick! Dundrum was often raided by native Irish people, who would come down from Wicklow. This was something that was happening all over the southern edge of the Pale. To improve the situation, land was often given to families, who in exchange would build and maintain fortifications. Thus, the Fitzwilliam family appears in Dundrum, who erected Dundrum Castle. Ruins of this castle can still be seen today. In 1816 the vast Fitzwilliam Estate was inherited by the 11th Earl of Pembroke. The estate - although reduced in size - still exists. One of its many possessions was land on which Gordonville would later be built, as we will see below. -

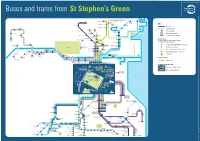

Buses and Trams from St Stephen's Green

142 Buses and trams from St Stephen’s Green 142 continues to Waterside, Seabury, Malahide, 32x continues to 41x Broomfield, Hazelbrook, Sainthelens and 15 Portmarnock, Swords Manor Portmarnock Sand’s Hotel Baldoyle Malahide and 142 Poppintree 140 Clongriffin Seabury Barrysparks Finglas IKEA KEY Charlestown SWORDS Main Street Ellenfield Park Darndale Beaumont Bus route Fosterstown (Boroimhe) Collinstown 14 Coolock North Blakestown (Intel) 11 44 Whitehall Bull Tram (Luas) line Wadelai Park Larkhill Island Finglas Road Collins Avenue Principal stop Donnycarney St Anne’s Park 7b Bus route terminus Maynooth Ballymun and Gardens (DCU) Easton Glasnevin Cemetery Whitehall Marino Tram (Luas) line terminus Glasnevin Dublin (Mobhi) Harbour Maynooth St Patrick’s Fairview Transfer Points (Kingsbury) Prussia Street 66x Phibsboro Locations where it is possible to change Drumcondra North Strand to a different form of transport Leixlip Mountjoy Square Rail (DART, COMMUTER or Intercity) Salesian College 7b 7d 46e Mater Connolly/ 67x Phoenix Park Busáras (Infirmary Road Tram (Luas Red line) Phoenix Park and Zoo) 46a Parnell Square 116 Lucan Road Gardiner Bus coach (regional or intercity) (Liffey Valley) Palmerstown Street Backweston O’Connell Street Lucan Village Esker Hill Abbey Street Park & Ride (larger car parks) Lower Ballyoulster North Wall/Beckett Bridge Ferry Port Lucan Chapelizod (142 Outbound stop only) Dodsboro Bypass Dublin Port Aghards 25x Islandbridge Heuston Celbridge Points of Interest Grand Canal Dock 15a 15b 145 Public Park Heuston Arran/Usher’s -

Irish Marriages, Being an Index to the Marriages in Walker's Hibernian

— .3-rfeb Marriages _ BBING AN' INDEX TO THE MARRIAGES IN Walker's Hibernian Magazine 1771 to 1812 WITH AN APPENDIX From the Notes cf Sir Arthur Vicars, f.s.a., Ulster King of Arms, of the Births, Marriages, and Deaths in the Anthologia Hibernica, 1793 and 1794 HENRY FARRAR VOL. II, K 7, and Appendix. ISSUED TO SUBSCRIBERS BY PHILLIMORE & CO., 36, ESSEX STREET, LONDON, [897. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1729519 3nK* ^ 3 n0# (Tfiarriages 177.1—1812. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com Seventy-five Copies only of this work printed, of u Inch this No. liS O&CLA^CV www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1 INDEX TO THE IRISH MARRIAGES Walker's Hibernian Magazine, 1 771 —-1812. Kane, Lt.-col., Waterford Militia = Morgan, Miss, s. of Col., of Bircligrove, Glamorganshire Dec. 181 636 ,, Clair, Jiggmont, co.Cavan = Scott, Mrs., r. of Capt., d. of Mr, Sampson, of co. Fermanagh Aug. 17S5 448 ,, Mary = McKee, Francis 1S04 192 ,, Lt.-col. Nathan, late of 14th Foot = Nesbit, Miss, s. of Matt., of Derrycarr, co. Leitrim Dec. 1802 764 Kathcrens, Miss=He\vison, Henry 1772 112 Kavanagh, Miss = Archbold, Jas. 17S2 504 „ Miss = Cloney, Mr. 1772 336 ,, Catherine = Lannegan, Jas. 1777 704 ,, Catherine = Kavanagh, Edm. 1782 16S ,, Edmund, BalIincolon = Kavanagh, Cath., both of co. Carlow Alar. 1782 168 ,, Patrick = Nowlan, Miss May 1791 480 ,, Rhd., Mountjoy Sq. = Archbold, Miss, Usher's Quay Jan. 1S05 62 Kavenagh, Miss = Kavena"gh, Arthur 17S6 616 ,, Arthur, Coolnamarra, co. Carlow = Kavenagh, Miss, d. of Felix Nov. 17S6 616 Kaye, John Lyster, of Grange = Grey, Lady Amelia, y.