Cultural Dimensions of Nontimber Forest Products

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Black Huckleberry Case Study in the Kootenay Region of British Columbia

Extension Note HOBBY AND KEEFER BC Journal of Ecosystems and Management A black huckleberry case study in the Kootenay region of British Columbia Tom Hobby1 and Michael E. Keefer2 Abstract This case study explores the commercial development of black huckleberries (Vaccinium membranaceum Dougl.) in the Kootenay region of British Columbia. Black huckleberries have a long history of human and wildlife use, and there are increasing demands on the resource in the region. Conflicts between commercial, traditional, and recreational users have emerged over expanding the harvest of this non-timber forest product (NTFP). This case study explores the potential for expanding huckleberry commercialization by examining the potential management and policy options that would support a sustainable commercial harvest. The article also reviews trends and issues within the huckleberry sector and ecological research currently conducted within the region. keywords: British Columbia; forest ecology; forest economic development; forest management; huckleberries; non-timber forest products; wildlife. Contact Information 1 Consultant, SCR Management Inc., PO Box 341, Malahat, BC V0R 2L0. Email: [email protected] 2 Principal, Keefer Ecological Services Ltd., 3816 Highland Road, Cranbrook, BC V1C 6X7. Email: [email protected] Editor’s Note: Please refer to Mitchell and Hobby (2010; see page 27) in this special issue for a description of the overall non-timber forest product project and details of the methodology employed in the case studies. JEM — VOLU me 11, NU M B E RS 1 AND 2 Published by FORREX Forum for Research and Extension in Natural Resources Hobby,52 T. and M.E. Keefer. 2010. A blackJEM huckleberry — VOLU me case 11, study NU M inB E RSthe 1 Kootenay AND 2 region of British Columbia. -

Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Kate, "Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole" (2012). All Theses. 1345. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SASSAFRAS TEA: USING A TRADITIONAL METHOD OF PREPARATION TO REDUCE THE CARCINOGENIC COMPOUND SAFROLE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Forest Resources by Kate Cummings May 2012 Accepted by: Patricia Layton, Ph.D., Committee Chair Karen C. Hall, Ph.D Feng Chen, Ph. D. Christina Wells, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to quantify the carcinogenic compound safrole in the traditional preparation method of making sassafras tea from the root of Sassafras albidum. The traditional method investigated was typical of preparation by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and other Appalachian peoples. Sassafras is a tree common to the eastern coast of the United States, especially in the mountainous regions. Historically and continuing until today, roots of the tree are used to prepare fragrant teas and syrups. -

Huckleberry Picking at Priest Lake

HUCKLEBERRY (Vaccinium Membranaceum) USDA Forest Service Other Common Names Northern Region Blueberry, Big Whortleberry, Black Idaho Panhandle Huckleberry, Bilberry. National Forests Description: The huckleberry is a low erect shrub, ranging from 1-5' tall. The flowers are shaped like tiny pink or white urns, which blossom in June and July, depending on elevation. The leaves are short, elliptical and alter- native on the stems. The bush turns brilliant red and sheds its leaves in the fall. The stem bark is reddish (often yellowish-green in shaded sites). The shape of the berry varies The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) from round to oval and the color var- prohibits discrimination in its programs on the basis ies from purplish black to wine- of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disa- colored red. Some species have a bility, political beliefs, and marital or familial status. dusky blue covering called bloom. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Per- The berries taste sweet and tart, in sons with disabilities who require alternative means the same proportions. of communication of program information (braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's Ripening Season: July-August TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). Early in the season, by mid-July, the berries on sunny southern facing To file a complaint, write the Secretary of Agriculture, Huckleberry slopes and lower elevations are first U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC to ripen. They are most succulent in 20250, or call 1-800-795-3272 (voice) or 202-720- mid-summer. However, good pick- 6382 (TDD). -

A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus Communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine

© 2021 JETIR March 2021, Volume 8, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine. A Review * Dr. Aafiya Nargis 1, Dr. Ansari Bilquees Mohammad Yunus 2, Dr. Sharique Zohaib 3, Dr. Qutbuddin Shaikh 4, Dr. Naeem Ahmed Shaikh 5 *1 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Niswan wa Qabalat, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon 2 Associate professor, Dept. Tashreeh ul Badan, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon. 3 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Saidla, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Manssoora, Malegaon 4 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Tahaffuzi wa Samaji Tibb, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. 5 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Ain, Uzn, Anf, Halaq wa Asnan, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. Abstract:- Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are 훼-pinene, 훽-pinene, apigenin, sabinene, 훽-sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others Juniperus communis L. (Abhal) is an evergreen aromatic shrub with high therapeutic potential in human diseases. This plant is loaded with nutrition and is rich in aromatic oils and their concentration differ in different parts of the plant (berries, leaves, aerial parts, and root). The fruit berries contain essential oil, invert sugars, resin, catechin , organic acid, terpenic acids, leucoanthocyanidin besides bitter compound (Juniperine), flavonoids, tannins, gums, lignins, wax, etc. -

Sacred Heart Game.Pmd

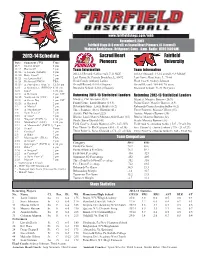

www.fairfieldstags.com/mbb November 9, 2013 Fairfield Stags (0-0 overall) vs Sacred Heart Pioneers. (0-0 overall) Webster Bank Arena - Bridgeport, Conn. - 8 pm - Radio : WICC (600 AM) 2013-14 Schedule Sacred Heart Fairfield Date Opponent (TV) Time Pioneers University 11/9 Sacred Heart! 8 pm 11/13 Hartford# 7 pm Team Information Team Information 11/16 at Loyola (MASN) 8 pm 11/20 Holy Cross# 7 pm 2012-13 Record: 9-20 overall, 7-11 NEC 2012-13 Record: 19-16 overall, 9-9 MAAC 11/23 vs. Louisville#^ 2 pm Last Game: St. Francis Brooklyn, L, 80-92 Last Game: Kent State, L, 73-60 11/24 Richmond/UNC#^ TBA Head Coach: Anthony Latina Head Coach: Sydney Johnson 11/29 at Providence (Fox 1) 12:30 pm Overall Record: 0-0 (1st Season) Overall Record: 105-84 (7th year) 12/6 at Quinnipiac (ESPN3)* 8:30 pm Record at School: 0-0 (1st Season) Record at School: 41-31 (3rd year) 12/8 Iona* 1:30 pm 12/11 at Belmont 7 pm CST Returning 2012-13 Statistical Leaders Returning 2012-13 Statistical Leaders 12/15 Northeastern (SNY) 1 pm 12/21 at Green Bay 1 pm CST Minutes: Phil Gaetano (35.3) Minutes: Maurice Barrow (26.9) 12/28 at Bucknell 2 pm Points/Game: Louis Montes (14.4) Points/Game: Maurice Barrow (8.9) 1/2 at Marist* 7 pm Rebounds/Game: Louis Montes (6.2) Rebounds/Game:Amadou Sidibe (6.2) 1/4 at Manhattan* 7 pm Three Pointers: Steve Glowiak (61) Three Pointers: Marcus Gilbert (35) 1/8 Saint Peter’s* 7 pm Assists: Phil Gaetano (222) Assists: Maruice Barrow (38) 1/10 at Iona* 7 pm Blocks: Louis Montes/Mostafa Abdel Latif (15) Blocks: Maurice Barrow (22) 1/16 Niagara* -

CASCADE BILBERRY Decorated with Bear Grass and Bitter Cherry Bark

Plant Guide baskets include "Klikitat baskets" of cedar root CASCADE BILBERRY decorated with bear grass and bitter cherry bark. Each family would harvest and store approximately Vaccinium deliciosum Piper four or five pecks (ca. four to five gallons) of dried Plant Symbol = VADE berries for winter use (Perkins n.d. (1838-43), Book 1:10). Hunn (1990) estimates that there were 28-42 Contributed by: USDA NRCS National Plant Data huckleberry harvest days in a year. This resulted in a Center & Oregon Plant Materials Center total annual harvest of 63.9-80.2 kg/woman/year from the Tenino-Wishram area, and 90 kg/woman/year from the Umatilla area. The net result was a huckleberry harvest yield of 31 kcal/person/day in the Tenino-Wishram area and 42 kcal/person/day for the Umatilla area (Hunn 1981: 130-131). Vaccinium species contain 622 Kcal per 100 gm huckleberries, with 15.3 gm carbohydrate, 0.5 gm fat, 0.7 gm protein and 83.2 gm water (Hunn 1981:130-131). In the fall, after the harvest, it was common for the Sahaptin to burn these areas to create favorable habitat (Henry Lewis 1973, 1977). Fire creates sunny openings in the forest and edges that foster the rapid spread of nutritious herbs and shrubs that favors the huckleberries (Minore 1972:68). The leaves and berries are high in vitamin C. The Jeanne Russell Janish leaves and finely chopped stems contain quinic acid, Used with permission of the publishers © Stanford University a former therapeutic for gout said to inhibit uric acid Abrams & Ferris (1960) formation but never widely used because of mixed clinical results. -

Tips for Cooking with Juniper Hunt Country Marinade

Recipes Tips for Cooking with Juniper • Juniper berries can be used fresh and are commonly sold dried as well. • Add juniper berries to brines and dry rubs for turkey, pork, beef, and wild game. • Berries are typically crushed before added to marinades and sauces. Hunt Country Marinade ¾ cup Cabernet Sauvignon or other dry red wine 3 large garlic cloves, minced ¼ cup balsamic vinegar 3 2x1-inch strips orange peel (orange part only) 3 tablespoons olive oil 3 2x1-inch strips lemon peel (yellow part only) 2 tablespoons unsulfured (light) molasses 8 whole cloves 2 tablespoons chopped fresh thyme or 2 8 whole black peppercorns teaspoons dried 2 bay leaves, broken in half 2 tablespoons chopped fresh rosemary or 2 ¾ teaspoon sa teaspoons dried 1 tablespoon crushed juniper berries or 2 tablespoons gin Mix all ingredients in a medium bowl. (Can be made 2 days ahead. Cover; chill.) Marinate poultry 2 to 4 hours and meat 6 to 12 hours in refrigerator. Drain marinade into saucepan. Boil 1 minute. Pat meat or poultry dry. Grill, basting occasionally with marinade. — Bon Appetit July 1995 via epicurious.com ©2016 by The Herb Society of America www.herbsociety.org 440-256-0514 9019 Kirtland Chardon Road, Kirtland, OH 44094 Recipes Pecan-Crusted Beef Tenderloin with Juniper Jus Two 2 ½ - pound well-trimmed center-cut 1 cup pecans, very finely chopped beef tenderloins, not tied 3 shallots, thinly sliced Salt and freshly ground pepper 1 carrot, thinly sliced 4 tablespoons unsalted butter 1 tablespoon tomato paste 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil 2 teaspoons dried juniper berries, crushed ¼ cup ketchup 1 ½ cups full-bodied red wine, such as Syrah ¼ cup Dijon mustard 1 cup beef demiglace (see Note) 4 large egg yolks Preheat the oven to 425°F. -

Porcelain Berry Are Aggressive , Growing Quickly to PORCELAIN Form Large Mats Over Existing Vegetation

The vines of porcelain berry are aggressive , growing quickly to PORCELAIN form large mats over existing vegetation. It easily climbs up and around BERRY trees, shading out shrubs and seedlings of native plants . (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata) CHARACTERISTICS WHERE FROM WHERE FOUND Y Porcelain berry is a woody, Native to Japan and China, Porcelain berry can be F perennial vine which can this plant was brought to found in southern New I grow up to 20 feet or more, North America in 1870 as England, the Mid-Atlantic T and closely resembles native an ornamental and land - and parts of the South and grapevine. The center, or scaping plant. Midwest. It can be found N pith, is white. Its bark has in varying conditions, from lenticels (light colored dots) dry to moist areas, along E and will not peel, unlike forest edges and streams, grape bark which does not as well as areas receiving PORCELAIN BERRY FOLIAGE D Karan A. Rawlins, University of Georgia, have lenticels and will full sunlight to partial shade. Bugwood.org I y peel or shred. It uses non- c Porcelain berry is not n a adhesive tendrils to climb. v tolerant of fully shaded sites r e s n Leaves are alternate and or wet soils. o C broadly ovate with a heart- e n i w shaped base. Leaves have y d n 3–5 lobes and toothed a r B PORCELAIN BERRY FRUITS margins. Porcelain berry | James H. Miller, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org Y produces small, hard berries R R E varying in color from pale B N I violet to green, to a bright A L E blue. -

Porcelain Berry

FACT SHEET: PORCELAIN-BERRY Porcelain-berry Ampelopsis brevipedunculata (Maxim.) Trautv. Grape family (Vitaceae) NATIVE RANGE Northeast Asia - China, Korea, Japan, and Russian Far East DESCRIPTION Porcelain-berry is a deciduous, woody, perennial vine. It twines with the help of non-adhesive tendrils that occur opposite the leaves and closely resembles native grapes in the genus Vitis. The stem pith of porcelain-berry is white (grape is brown) and continuous across the nodes (grape is not), the bark has lenticels (grape does not), and the bark does not peel (grape bark peels or shreds). The Ieaves are alternate, broadly ovate with a heart-shaped base, palmately 3-5 lobed or more deeply dissected, and have coarsely toothed margins. The inconspicuous, greenish-white flowers with "free" petals occur in cymes opposite the leaves from June through August (in contrast to grape species that have flowers with petals that touch at tips and occur in panicles. The fruits appear in September-October and are colorful, changing from pale lilac, to green, to a bright blue. Porcelain-berry is often confused with species of grape (Vitis) and may be confused with several native species of Ampelopsis -- Ampelopsis arborea and Ampelopsis cordata. ECOLOGICAL THREAT Porcelain-berry is a vigorous invader of open and wooded habitats. It grows and spreads quickly in areas with high to moderate light. As it spreads, it climbs over shrubs and other vegetation, shading out native plants and consuming habitat. DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES Porcelain-berry is found from New England to North Carolina and west to Michigan (USDA Plants) and is reported to be invasive in twelve states in the Northeast: Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, Washington D.C., West Virginia, and Wisconsin. -

Chapter 1 Definitions and Classifications for Fruit and Vegetables

Chapter 1 Definitions and classifications for fruit and vegetables In the broadest sense, the botani- Botanical and culinary cal term vegetable refers to any plant, definitions edible or not, including trees, bushes, vines and vascular plants, and Botanical definitions distinguishes plant material from ani- Broadly, the botanical term fruit refers mal material and from inorganic to the mature ovary of a plant, matter. There are two slightly different including its seeds, covering and botanical definitions for the term any closely connected tissue, without vegetable as it relates to food. any consideration of whether these According to one, a vegetable is a are edible. As related to food, the plant cultivated for its edible part(s); IT botanical term fruit refers to the edible M according to the other, a vegetable is part of a plant that consists of the the edible part(s) of a plant, such as seeds and surrounding tissues. This the stems and stalk (celery), root includes fleshy fruits (such as blue- (carrot), tuber (potato), bulb (onion), berries, cantaloupe, poach, pumpkin, leaves (spinach, lettuce), flower (globe tomato) and dry fruits, where the artichoke), fruit (apple, cucumber, ripened ovary wall becomes papery, pumpkin, strawberries, tomato) or leathery, or woody as with cereal seeds (beans, peas). The latter grains, pulses (mature beans and definition includes fruits as a subset of peas) and nuts. vegetables. Definition of fruit and vegetables applicable in epidemiological studies, Fruit and vegetables Edible plant foods excluding -

Alaska Non-Timber Forest Products Harvest Manual for Commercial Harvest on State-Owned Lands

Alaska Non-Timber Forest Products Harvest Manual For Commercial Harvest on State-Owned Lands State of Alaska Department of Natural Resources Division of Mining, Land and Water April 2, 2008 - 1 - State of Alaska Non-Timber Forest Product Commercial Harvest Manual, April 2, 2008 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Special notices, clarifications, and general rules 4 Procedure for revision 5 Products and species descriptions 6 Bark birch 7 cedar 8 various species 9 Berries and berry-like fruits 10 Branches and stems of deciduous woody species 11 Buds and tips 12 Burls and galls 13 Cones 14 Conks 15 Cuttings – willow, dogwood & poplar 16 Diamond willow 17 Evergreen boughs 18 Floral greenery 19 Leaves and flowers of woody plants 20 Lichens ground-growing 21 tree-growing 22 Mosses and liverworts 23 Mushrooms 24 Non-woody perennial plants tender edible shoots, stems, leaves, and/or flowers 25 mature stems, leaves and flowers 26 Roots edible or medicinal 27 for fiber 28 Seed heads 29 Seeds 30 Transplants plugs 31 shrubby perennial with root ball 32 sprigs 33 tree sapling with root ball 34 Appendix I: Plants never allowed for harvest 35 Appendix II: Guidelines for non over-the-counter permit products 36 Glossary 38 Selected references 39 - 2 - State of Alaska Non-Timber Forest Product Commercial Harvest Manual, April 2, 2008 Introduction Non-timber forest products are generally defined as products derived from biological resources. Examples of non-timber forest products may include mushrooms, conks, boughs, cones, leaves, burls, landscaping transplants, roots, flowers, fruits, and berries. Not included are minerals, rocks, soil, water, animals, and animal parts. -

Applying Landscape Ecology to Improve Strawberry Sap Beetle

Applying Landscape The lack of effective con- trol measures for straw- Ecology to Improve berry sap beetle is a problem at many farms. Strawberry Sap Beetle The beetles appear in strawberry fi elds as the Management berries ripen. The adult beetle feeds on the un- Rebecca Loughner and Gregory Loeb derside of berries creat- Department of Entomology ing holes, and the larvae Cornell University, NYSAES, Geneva, NY contaminate harvestable he strawberry sap beetle (SSB), fi eld sanitation, and renovating promptly fruit leading to consumer Stelidota geminata, is a significant after harvest. Keeping fi elds suffi ciently complaints and the need T insect pest in strawberry in much of clean of ripe and overripe fruit is nearly the Northeast. The small, brown adults impossible, especially for U-pick op- to prematurely close (Figure 1) are approximately 1/16 inch in erations, and the effectiveness of the two length and appear in strawberry fi elds as labeled pyrethroids in the fi eld is highly fi elds at great cost to the the berries ripen. The adult beetle feeds variable. Both Brigade [bifenthrin] and grower. Our research has on the underside of berries creating holes. Danitol [fenpropathrin] have not provided Beetles prefer to feed on over-ripe fruit but suffi cient control in New York and since shown that the beetles do will also damage marketable berries. Of they are broad spectrum insecticides they not overwinter in straw- more signifi cant concern, larvae contami- can potentially disrupt predatory mite nate harvestable fruit leading to consumer populations that provide spider mite con- berry fi elds.