Big Game Hunting Practices, Meanings, Motivations And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Kate, "Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole" (2012). All Theses. 1345. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SASSAFRAS TEA: USING A TRADITIONAL METHOD OF PREPARATION TO REDUCE THE CARCINOGENIC COMPOUND SAFROLE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Forest Resources by Kate Cummings May 2012 Accepted by: Patricia Layton, Ph.D., Committee Chair Karen C. Hall, Ph.D Feng Chen, Ph. D. Christina Wells, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to quantify the carcinogenic compound safrole in the traditional preparation method of making sassafras tea from the root of Sassafras albidum. The traditional method investigated was typical of preparation by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and other Appalachian peoples. Sassafras is a tree common to the eastern coast of the United States, especially in the mountainous regions. Historically and continuing until today, roots of the tree are used to prepare fragrant teas and syrups. -

A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus Communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine

© 2021 JETIR March 2021, Volume 8, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine. A Review * Dr. Aafiya Nargis 1, Dr. Ansari Bilquees Mohammad Yunus 2, Dr. Sharique Zohaib 3, Dr. Qutbuddin Shaikh 4, Dr. Naeem Ahmed Shaikh 5 *1 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Niswan wa Qabalat, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon 2 Associate professor, Dept. Tashreeh ul Badan, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon. 3 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Saidla, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Manssoora, Malegaon 4 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Tahaffuzi wa Samaji Tibb, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. 5 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Ain, Uzn, Anf, Halaq wa Asnan, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. Abstract:- Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are 훼-pinene, 훽-pinene, apigenin, sabinene, 훽-sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others Juniperus communis L. (Abhal) is an evergreen aromatic shrub with high therapeutic potential in human diseases. This plant is loaded with nutrition and is rich in aromatic oils and their concentration differ in different parts of the plant (berries, leaves, aerial parts, and root). The fruit berries contain essential oil, invert sugars, resin, catechin , organic acid, terpenic acids, leucoanthocyanidin besides bitter compound (Juniperine), flavonoids, tannins, gums, lignins, wax, etc. -

Sacred Heart Game.Pmd

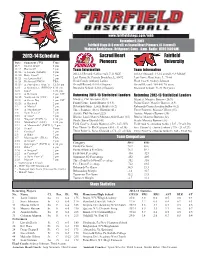

www.fairfieldstags.com/mbb November 9, 2013 Fairfield Stags (0-0 overall) vs Sacred Heart Pioneers. (0-0 overall) Webster Bank Arena - Bridgeport, Conn. - 8 pm - Radio : WICC (600 AM) 2013-14 Schedule Sacred Heart Fairfield Date Opponent (TV) Time Pioneers University 11/9 Sacred Heart! 8 pm 11/13 Hartford# 7 pm Team Information Team Information 11/16 at Loyola (MASN) 8 pm 11/20 Holy Cross# 7 pm 2012-13 Record: 9-20 overall, 7-11 NEC 2012-13 Record: 19-16 overall, 9-9 MAAC 11/23 vs. Louisville#^ 2 pm Last Game: St. Francis Brooklyn, L, 80-92 Last Game: Kent State, L, 73-60 11/24 Richmond/UNC#^ TBA Head Coach: Anthony Latina Head Coach: Sydney Johnson 11/29 at Providence (Fox 1) 12:30 pm Overall Record: 0-0 (1st Season) Overall Record: 105-84 (7th year) 12/6 at Quinnipiac (ESPN3)* 8:30 pm Record at School: 0-0 (1st Season) Record at School: 41-31 (3rd year) 12/8 Iona* 1:30 pm 12/11 at Belmont 7 pm CST Returning 2012-13 Statistical Leaders Returning 2012-13 Statistical Leaders 12/15 Northeastern (SNY) 1 pm 12/21 at Green Bay 1 pm CST Minutes: Phil Gaetano (35.3) Minutes: Maurice Barrow (26.9) 12/28 at Bucknell 2 pm Points/Game: Louis Montes (14.4) Points/Game: Maurice Barrow (8.9) 1/2 at Marist* 7 pm Rebounds/Game: Louis Montes (6.2) Rebounds/Game:Amadou Sidibe (6.2) 1/4 at Manhattan* 7 pm Three Pointers: Steve Glowiak (61) Three Pointers: Marcus Gilbert (35) 1/8 Saint Peter’s* 7 pm Assists: Phil Gaetano (222) Assists: Maruice Barrow (38) 1/10 at Iona* 7 pm Blocks: Louis Montes/Mostafa Abdel Latif (15) Blocks: Maurice Barrow (22) 1/16 Niagara* -

Tips for Cooking with Juniper Hunt Country Marinade

Recipes Tips for Cooking with Juniper • Juniper berries can be used fresh and are commonly sold dried as well. • Add juniper berries to brines and dry rubs for turkey, pork, beef, and wild game. • Berries are typically crushed before added to marinades and sauces. Hunt Country Marinade ¾ cup Cabernet Sauvignon or other dry red wine 3 large garlic cloves, minced ¼ cup balsamic vinegar 3 2x1-inch strips orange peel (orange part only) 3 tablespoons olive oil 3 2x1-inch strips lemon peel (yellow part only) 2 tablespoons unsulfured (light) molasses 8 whole cloves 2 tablespoons chopped fresh thyme or 2 8 whole black peppercorns teaspoons dried 2 bay leaves, broken in half 2 tablespoons chopped fresh rosemary or 2 ¾ teaspoon sa teaspoons dried 1 tablespoon crushed juniper berries or 2 tablespoons gin Mix all ingredients in a medium bowl. (Can be made 2 days ahead. Cover; chill.) Marinate poultry 2 to 4 hours and meat 6 to 12 hours in refrigerator. Drain marinade into saucepan. Boil 1 minute. Pat meat or poultry dry. Grill, basting occasionally with marinade. — Bon Appetit July 1995 via epicurious.com ©2016 by The Herb Society of America www.herbsociety.org 440-256-0514 9019 Kirtland Chardon Road, Kirtland, OH 44094 Recipes Pecan-Crusted Beef Tenderloin with Juniper Jus Two 2 ½ - pound well-trimmed center-cut 1 cup pecans, very finely chopped beef tenderloins, not tied 3 shallots, thinly sliced Salt and freshly ground pepper 1 carrot, thinly sliced 4 tablespoons unsalted butter 1 tablespoon tomato paste 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil 2 teaspoons dried juniper berries, crushed ¼ cup ketchup 1 ½ cups full-bodied red wine, such as Syrah ¼ cup Dijon mustard 1 cup beef demiglace (see Note) 4 large egg yolks Preheat the oven to 425°F. -

Spice Basics

SSpicepice BasicsBasics AAllspicellspice Allspice has a pleasantly warm, fragrant aroma. The name refl ects the pungent taste, which resembles a peppery compound of cloves, cinnamon and nutmeg or mace. Good with eggplant, most fruit, pumpkins and other squashes, sweet potatoes and other root vegetables. Combines well with chili, cloves, coriander, garlic, ginger, mace, mustard, pepper, rosemary and thyme. AAnisenise The aroma and taste of the seeds are sweet, licorice like, warm, and fruity, but Indian anise can have the same fragrant, sweet, licorice notes, with mild peppery undertones. The seeds are more subtly fl avored than fennel or star anise. Good with apples, chestnuts, fi gs, fi sh and seafood, nuts, pumpkin and root vegetables. Combines well with allspice, cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, fennel, garlic, nutmeg, pepper and star anise. BBasilasil Sweet basil has a complex sweet, spicy aroma with notes of clove and anise. The fl avor is warming, peppery and clove-like with underlying mint and anise tones. Essential to pesto and pistou. Good with corn, cream cheese, eggplant, eggs, lemon, mozzarella, cheese, olives, pasta, peas, pizza, potatoes, rice, tomatoes, white beans and zucchini. Combines well with capers, chives, cilantro, garlic, marjoram, oregano, mint, parsley, rosemary and thyme. BBayay LLeafeaf Bay has a sweet, balsamic aroma with notes of nutmeg and camphor and a cooling astringency. Fresh leaves are slightly bitter, but the bitterness fades if you keep them for a day or two. Fully dried leaves have a potent fl avor and are best when dried only recently. Good with beef, chestnuts, chicken, citrus fruits, fi sh, game, lamb, lentils, rice, tomatoes, white beans. -

Non-Timber Forest Products and Their Contribution to Households Income

Suleiman et al. Ecological Processes (2017) 6:23 DOI 10.1186/s13717-017-0090-8 RESEARCH Open Access Non-timber forest products and their contribution to households income around Falgore Game Reserve in Kano, Nigeria Muhammad Sabiu Suleiman1*, Vivian Oliver Wasonga1, Judith Syombua Mbau1, Aminu Suleiman2 and Yazan Ahmed Elhadi1 Abstract Introduction: In the recent decades, there has been growing interest in the contribution of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) to livelihoods, development, and poverty alleviation among the rural populace. This has been prompted by the fact that communities living adjacent to forest reserves rely to a great extent on the NTFPs for their livelihoods, and therefore any effort to conserve such resources should as a prerequisite understand how the host communities interact with them. Methods: Multistage sampling technique was used for the study. A representative sample of 400 households was used to explore the utilization of NTFPs and their contribution to households’ income in communities proximate to Falgore Game Reserve (FGR) in Kano State, Nigeria. Descriptive statistics and logistic regression analysis were used to analyze and summarize the data collected. Results: The findings reveal that communities proximate to FGR mostly rely on the reserve for firewood, medicinal herbs, fodder, and fruit nuts for household use and sales. Income from NTFPs accounts for 20–60% of the total income of most (68%) of the sampled households. The utilization of NTFPs was significantly influenced by age, sex, household size, main occupation, distance to forest and market. Conclusions: The findings suggest that NTFPs play an important role in supporting livelihoods, and therefore provide an important safety net for households throughout the year particularly during periods of hardship occasioned by drought. -

Texas Wildlife Identification Guide: a Guide to Game Animals, Game

texas parks and wildlife TEXAS WILDLIFE IDENTIFICATION GUIDE A guide to game animals, game birds, furbearers and other wildlife of Texas. INTRODUCTION TEXAS game animals, game birds, furbearers and other wildlife are important for many reasons. They provide countless hours of viewing and recreational opportunities.They benefit the Texas economy through hunting and “nature tourism” such as birdwatching. Commercial businesses that provide birdseed, dry corn and native landscaping may be devoted solely to attracting many of the animals found in this book. Local hunting and trapping economies, guiding operations and hunting leases have prospered because of the abun- dance of these animals in Texas.The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department benefits because of hunting license sales, but it uses these funds to research, manage and pro- tect all wildlife populations – not just game animals. Game animals provide humans with cultural, social, aesthetic and spiritual pleasures found in wildlife art, taxi- dermy and historical artifacts. Conservation organizations dedicated to individual species such as quail, turkey and deer, have funded thousands of wildlife projects throughout North America, demonstrating the mystique game animals have on people. Animals referenced in this pocket guide exist because their habitat exists in Texas. Habitat is food, cover, water and space, all suitably arranged.They are part of a vast food chain or web that includes thousands more species of wildlife such as the insects, non-game animals, fish and i rare/endangered species. Active management of wild landscapes is the primary means to continue having abundant populations of wildlife in Texas. Preservation of rare and endangered habitat is one way of saving some species of wildlife such as the migratory whooping crane that makes Texas its home in the winter. -

Bbq Smokehouse Custom and Wild Game Processing Rates

BBQ SMOKEHOUSE CUSTOM AND WILD GAME PROCESSING RATES SUMMER SAUSAGE REGULAR SUMMER SAUSAGE $2.80 # CHEDDAR SUMMER SAUSAGE $3.40 # PEPPERJACK SUMMER SAUSAGE $3.40 # JALAPENO CHEDDAR SUMMER SAUSAGE $3.75 # TANGY SUMMER SAUSAGE $3.25 # GARLIC SUMMER SAUSAGE $3.10 # WILD RICE SUMMER SAUSAGE $3.75 # BLUEBERRY WILD RICE SUMMER SAUSAGE $3.90# SMOKED BRATS SMOKED BRAT REGULAR $3.25 # SMOKED CHEDDAR & WILD RICE BRAT $3.75 # SMOKED CHEDDAR BRAT $3.50 # SMOKED WILD RICE BRAT $3.75 # SMOKED MUSHROOM & SWISS BRAT $3.75 # SMOKED SWISS BRAT $3.60 # SMOKED JALAPENO CHEDDAR BRAT $3.75 # SMOKED CRANBERRY CHEDDAR BRAT $3.75 # SMOKED BUFFALO WILD WING BLEU CHEESE BRAT $4.40 # SMOKED TEX MEX BRAT $3.10# BAHAMA MAMA $3.40 # FRESH BRATS All fresh brats $3.25 # FRESH REGULAR BRAT FRESH CHEDDAR BRAT FRESH WILD RICE BRAT FRESH BLUEBERRY BRAT FRESH BLUEBERRY WILD RICE BRAT FRESH HAWAIIAN BRAT FRESH PHILLY CHEESE BRAT FRESH BACON CHEESEBURGER BRAT FRESH GREEN PEPPER & ONION BRAT FRESH ONION BRAT FRESH CHERRY CAYENNE BRAT FRESH JALAPENO BRAT FRESH BEER BRAT FRESH PIZZA BRAT FRESH TACO BRAT FRESH HONEY BBQ BRAT FRESH STEAK BRAT SMOKED SAUSAGES RING BOLOGNA $2.85 # ANDOUILLE SAUSAGE $3.40 # CHORIZO SAUSAGE $3.40 # POLISH SAUSAGE $2.65 # HOT POLISH SAUSAGE $3.00 # OLD FASHIONED WIENER $4.65 # CHEDDAR WIENER $5.30 # SNACK STIX AWARD WINNNING PEPPERJACK STIX $4.25 # REGULAR STIX $3.50 # PINEAPPLE TERIYAKI STIX $5.25 # TERIYAKI STIX $4.90 # CHEDDAR STIX $4.25 # JALAPENO STIX $3.90 # HABENERO BBQ STIX $4.90 # BBQ STIX $4.90# BREAKFAST SAUSAGES BREAKFAST SAUSAGE LINKS- REGULAR, -

2,000 Trees a Day: Work and Life in the American Naval Stores Industry, 1877 to 1940 by Catherine Kim Gyllerstrom a Dissertatio

2,000 Trees a Day: Work and Life in the American Naval Stores Industry, 1877 to 1940 by Catherine Kim Gyllerstrom A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 13, 2014 Keywords: Naval Stores, Turpentine, African American, Labor, Convict Lease, Debt Peonage Copyright 2014 by Catherine Kim Gyllerstrom Approved by Jennifer Brooks, Chair, Professor of History Ruth Crocker, Professor of History Angela Lakwete, Professor of History Tiffany Sippial, Professor of History Abstract This project explores the lives of nineteenth and early twentieth century naval stores workers in Alabama, Georgia, and Florida. After the Civil War, turpentine operators faced a high demand for their product, limited capital to embark on new operations, and an uncertain labor supply. Therefore, these men resorted to deceitful labor recruitment tactics to entice free workers to their camps. In addition, operators also supplemented their work force with convict labor. The preliminary focus of this dissertation is the experience—nature of work, work culture, and daily life—of turpentine employees. Previous historians, with the exception of Robert Outland, have dismissed turpentine harvesting as a makeshift operation on the periphery of civilization. In turn, this assessment has led to the misconception that turpentine workers were wild and violent frontiersmen, who rarely formed social bonds, idolized outlaws, and ascribed to a rough and tumble way of life. This work seeks to restore the reputation of naval stores laborers and contends that these men—both African American and white, both free and captive—shared a similar work culture to other industrial workers and established and supported families within the camps. -

Fresh Story | Blueberries | Story Fresh Thank You, Bees! Thank You, Means Ripe Blueberries in the Summer

PRIMARY fresh story | blueberries B IS FOR BLUEBERRY AND BRITISH COLUMBIA! The blueberries you are enjoying today were grown by a berry farmer right here in BC and are from a highbush blueberry plant. Blueberry bushes need rich soil, a long growing season, and weather that’s not too cold and not too hot. That’s why the Fraser Valley and Vancouver Island are some of the best blueberry growing areas in the world. Farm-grown blueberries are carefully planted in straight rows, while wild blueberries grow naturally on small bushes, called “lowbush,” that grow close to the ground. You have to kneel down to pick a wild blueberry! First Peoples have been harvesting wild blueberries from Canada’s forests, rocky hills, and boggy areas for thousands of years. Farm-grown or wild, blueberries are a tasty, healthy snack. Big or Small, Eat Them All You can’t tell a blueberry’s ripeness or sweetness based on its size. As long as they’re dark blue or purple, even small ones will be delicious. who’s in the hive? Thousands of honeybees live together in colonies in wooden houses provided by beekeepers. Inside these beehives every bee has a job. QUEEN BEE The queen is the biggest bee in the hive. There's only one queen, and she is the mother of all the bees. Photo credit- Spring Advertising DRONE BEES A drone is a male bee. A drone has no stinger. His only job is to mate Thank You, Bees! with the queen. To grow blueberries for you, farmers need help from WORKER BEES bees. -

• 5 Plants- Skunk Cabbage, Sassafras Tree, Cross Vine, Royal Fern, Trumpet

5 plants- skunk cabbage, sassafras tree, cross vine, royal fern, trumpet vine 5 insects/ arachnids- six-spotted fishing spider, green darner dragon fly, ground beetle, mud dauber, black swallowtail caterpillar 3 reptiles or amphibians- Eastern river cooter, marbled salamander, Fowler’s toad 3 fish- longear sunfish, walleye, smallmouth bass 3 water birds- king fisher, egret, blue heron 2 raptors- red-shouldered hawk, great-horned owl 3 small mammals- muskrat, Elliot’s short-tailed shrew, Eastern cottontail rabbit 2 medium mammals- mink, raccoon 2 large mammals- black bears, white-tailed deer 3 decomposers- fungus, white- nosed fungus syndrome, morel mushroom, pill bug 3 non-living components Skunk cabbage is a perennial wildflower that grows in swampy, wet areas of forest lands. This unusual plant sprouts very early in the spring, and has an odd chemistry that creates its own heat, often melting the snow around itself as it first sprouts in the spring. While the first sprout, a pod-like growth, looks like something out of a science-fiction movie, the skunk cabbage is a plain-looking green plant once the leaves appear. You may find two common types: Eastern skunk cabbage, which is purple, and Western skunk cabbage, which is yellow. Skunk cabbage gets its name from the fact that, when the leaves are crushed or bruised, it gives off a smell of skunk or rotting meat. Skunk cabbage is eaten by wood ducks, honey bees, and the eastern forest snail. The sassafras tree is known for its brilliant display of autumn foliage and aromatic smell. The species are unusual in having three distinct leaf patterns on the same plant: unlobed oval, bilobed (mitten-shaped), and trilobed (three-pronged). -

2021 Hunting and Trapping Regulations

Effective July through2021 June 30, 2022 Updated 9.10.21 MINNESOTA HUNTING & TRAPPING REGULATIONS SHARE THE PASSION mndnr.gov/hunting #huntmn Paid Advertisement FIREWOOD ALERT! You have the power to protect forests and trees! Pests like the invasive Buy locally harvested firewood at emerald ash borer can or near your destination. hitchhike in your firewood. Buy certified heat-treated firewood You can prevent the spread ahead of time, if available. of these damaging insects and diseases by following Gather firewood on site when these firewood tips: permitted. What might be in your firewood? GYPSY MOTH is a devastati ng pest SPOTTED LANTERNFLY sucks sap from of oaks and other trees. Female dozens of tree and plant species. This pest moths lay tan patches of eggs on loves tree-of-heaven but will feed on black fi rewood, campers, vehicles, pati o walnut, white oak, sycamore, and grape. furniture — anything outside! When Like the gypsy moth, this pest lays clusters these items are moved to new areas, of eggs on just about any dry surface, from this pest gets a free ride. landscaping stone to fi rewood! ASIAN LONGHORNED BEETLE will EMERALD ASH BORER — the infamous tunnel through, and destroy, over killer of ash trees — is found in forests 20 species of trees — especially and city trees across much of the eastern maple trees. The larvae of this and central United States. This insect is beetle bore into tree branches and notoriously good at hitching rides in infested trunks, making it an easy pest to fi rewood. Don’t give this tree-killing bug a accidentally transport in fi rewood.