Non-Timber Forest Products and Their Contribution to Households Income

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Kate, "Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole" (2012). All Theses. 1345. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SASSAFRAS TEA: USING A TRADITIONAL METHOD OF PREPARATION TO REDUCE THE CARCINOGENIC COMPOUND SAFROLE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Forest Resources by Kate Cummings May 2012 Accepted by: Patricia Layton, Ph.D., Committee Chair Karen C. Hall, Ph.D Feng Chen, Ph. D. Christina Wells, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to quantify the carcinogenic compound safrole in the traditional preparation method of making sassafras tea from the root of Sassafras albidum. The traditional method investigated was typical of preparation by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and other Appalachian peoples. Sassafras is a tree common to the eastern coast of the United States, especially in the mountainous regions. Historically and continuing until today, roots of the tree are used to prepare fragrant teas and syrups. -

A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus Communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine

© 2021 JETIR March 2021, Volume 8, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine. A Review * Dr. Aafiya Nargis 1, Dr. Ansari Bilquees Mohammad Yunus 2, Dr. Sharique Zohaib 3, Dr. Qutbuddin Shaikh 4, Dr. Naeem Ahmed Shaikh 5 *1 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Niswan wa Qabalat, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon 2 Associate professor, Dept. Tashreeh ul Badan, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon. 3 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Saidla, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Manssoora, Malegaon 4 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Tahaffuzi wa Samaji Tibb, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. 5 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Ain, Uzn, Anf, Halaq wa Asnan, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. Abstract:- Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are 훼-pinene, 훽-pinene, apigenin, sabinene, 훽-sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others Juniperus communis L. (Abhal) is an evergreen aromatic shrub with high therapeutic potential in human diseases. This plant is loaded with nutrition and is rich in aromatic oils and their concentration differ in different parts of the plant (berries, leaves, aerial parts, and root). The fruit berries contain essential oil, invert sugars, resin, catechin , organic acid, terpenic acids, leucoanthocyanidin besides bitter compound (Juniperine), flavonoids, tannins, gums, lignins, wax, etc. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Human Activities

4 Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Human Activities CO-CHAIRS D. Kupfer (Germany, Fed. Rep.) R. Karimanzira (Zimbabwe) CONTENTS AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY, AND OTHER HUMAN ACTIVITIES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 77 4.1 INTRODUCTION 85 4.2 FOREST RESPONSE STRATEGIES 87 4.2.1 Special Issues on Boreal Forests 90 4.2.1.1 Introduction 90 4.2.1.2 Carbon Sinks of the Boreal Region 90 4.2.1.3 Consequences of Climate Change on Emissions 90 4.2.1.4 Possibilities to Refix Carbon Dioxide: A Case Study 91 4.2.1.5 Measures and Policy Options 91 4.2.1.5.1 Forest Protection 92 4.2.1.5.2 Forest Management 92 4.2.1.5.3 End Uses and Biomass Conversion 92 4.2.2 Special Issues on Temperate Forests 92 4.2.2.1 Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Temperate Forests 92 4.2.2.2 Global Warming: Impacts and Effects on Temperate Forests 93 4.2.2.3 Costs of Forestry Countermeasures 93 4.2.2.4 Constraints on Forestry Measures 94 4.2.3 Special Issues on Tropical Forests 94 4.2.3.1 Introduction to Tropical Deforestation and Climatic Concerns 94 4.2.3.2 Forest Carbon Pools and Forest Cover Statistics 94 4.2.3.3 Estimates of Current Rates of Forest Loss 94 4.2.3.4 Patterns and Causes of Deforestation 95 4.2.3.5 Estimates of Current Emissions from Forest Land Clearing 97 4.2.3.6 Estimates of Future Forest Loss and Emissions 98 4.2.3.7 Strategies to Reduce Emissions: Types of Response Options 99 4.2.3.8 Policy Options 103 75 76 IPCC RESPONSE STRATEGIES WORKING GROUP REPORTS 4.3 AGRICULTURE RESPONSE STRATEGIES 105 4.3.1 Summary of Agricultural Emissions of Greenhouse Gases 105 4.3.2 Measures and -

{L' 7 3-,\O Tfmeat Novem Ber 2002 [,:.R'nroini.;Tion

AFRICAN PROGRAMME, FOR ONCHOCE,RCIASIS CONTROL (APOC) Forth Year Technical RePort for Community Directed Treatment with Ivermectin (cDrI) Dambatta Bichi Lbasawa Begwei Shanono Ajingi Gwarzo Kabo Gaya Wudil Kiru Bebcii Rano Karaye Takai Sumaila Doguwa Lp L For Acu-,,, I r.. ..4+ Caoa5 C5D Kano State clE' . l.r Nigeria p il, /{l' 7 3-,\o tfmeat Novem ber 2002 [,:.r'nroini.;tion Tr-r,_ I pr_ A'"' EXECUTTVE SUMMARY Kano State is situated in the northern part of Nigeria. The State has 44local govemment areas out of which 18 are Meso endemic with few hyper-endemic foci. The State falls in the Sudan Savannah and Sahel zones. Howeyer, the endemic areas are generally located in the Sudan savannah. The Ivermectin Distribution Programme (IDP) is in the 7th treatment round in some of the LGAs while in the 6th treatment round in others. However, CDTI strategy started in 1999. The CDTI project is therefore implemented in 779 communities of the 18 APOC approved local governments. Mobilization of the community members was conducted in all the targeted communities. In addition to mobilization, the state officials conducted advocacy visits to all the endemic local government Areas. The Launching of the commencement of 2002 prograrnme, which was performed by His Excellency, the Deputy Governor of Kano State increased awareness and acceptance of Mectizan by the people in the State. Electronic media, town criers and CDDs were among the mobilization strategies adopted for community mobilization. Targeted Training and re-training of CDTI programme personnel was conducted at state, LGA, and community levels, for those that are new in the programme as well as those with training dfficulties. -

Sacred Heart Game.Pmd

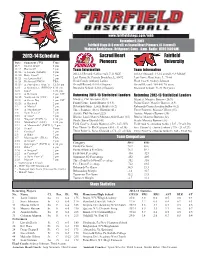

www.fairfieldstags.com/mbb November 9, 2013 Fairfield Stags (0-0 overall) vs Sacred Heart Pioneers. (0-0 overall) Webster Bank Arena - Bridgeport, Conn. - 8 pm - Radio : WICC (600 AM) 2013-14 Schedule Sacred Heart Fairfield Date Opponent (TV) Time Pioneers University 11/9 Sacred Heart! 8 pm 11/13 Hartford# 7 pm Team Information Team Information 11/16 at Loyola (MASN) 8 pm 11/20 Holy Cross# 7 pm 2012-13 Record: 9-20 overall, 7-11 NEC 2012-13 Record: 19-16 overall, 9-9 MAAC 11/23 vs. Louisville#^ 2 pm Last Game: St. Francis Brooklyn, L, 80-92 Last Game: Kent State, L, 73-60 11/24 Richmond/UNC#^ TBA Head Coach: Anthony Latina Head Coach: Sydney Johnson 11/29 at Providence (Fox 1) 12:30 pm Overall Record: 0-0 (1st Season) Overall Record: 105-84 (7th year) 12/6 at Quinnipiac (ESPN3)* 8:30 pm Record at School: 0-0 (1st Season) Record at School: 41-31 (3rd year) 12/8 Iona* 1:30 pm 12/11 at Belmont 7 pm CST Returning 2012-13 Statistical Leaders Returning 2012-13 Statistical Leaders 12/15 Northeastern (SNY) 1 pm 12/21 at Green Bay 1 pm CST Minutes: Phil Gaetano (35.3) Minutes: Maurice Barrow (26.9) 12/28 at Bucknell 2 pm Points/Game: Louis Montes (14.4) Points/Game: Maurice Barrow (8.9) 1/2 at Marist* 7 pm Rebounds/Game: Louis Montes (6.2) Rebounds/Game:Amadou Sidibe (6.2) 1/4 at Manhattan* 7 pm Three Pointers: Steve Glowiak (61) Three Pointers: Marcus Gilbert (35) 1/8 Saint Peter’s* 7 pm Assists: Phil Gaetano (222) Assists: Maruice Barrow (38) 1/10 at Iona* 7 pm Blocks: Louis Montes/Mostafa Abdel Latif (15) Blocks: Maurice Barrow (22) 1/16 Niagara* -

Tips for Cooking with Juniper Hunt Country Marinade

Recipes Tips for Cooking with Juniper • Juniper berries can be used fresh and are commonly sold dried as well. • Add juniper berries to brines and dry rubs for turkey, pork, beef, and wild game. • Berries are typically crushed before added to marinades and sauces. Hunt Country Marinade ¾ cup Cabernet Sauvignon or other dry red wine 3 large garlic cloves, minced ¼ cup balsamic vinegar 3 2x1-inch strips orange peel (orange part only) 3 tablespoons olive oil 3 2x1-inch strips lemon peel (yellow part only) 2 tablespoons unsulfured (light) molasses 8 whole cloves 2 tablespoons chopped fresh thyme or 2 8 whole black peppercorns teaspoons dried 2 bay leaves, broken in half 2 tablespoons chopped fresh rosemary or 2 ¾ teaspoon sa teaspoons dried 1 tablespoon crushed juniper berries or 2 tablespoons gin Mix all ingredients in a medium bowl. (Can be made 2 days ahead. Cover; chill.) Marinate poultry 2 to 4 hours and meat 6 to 12 hours in refrigerator. Drain marinade into saucepan. Boil 1 minute. Pat meat or poultry dry. Grill, basting occasionally with marinade. — Bon Appetit July 1995 via epicurious.com ©2016 by The Herb Society of America www.herbsociety.org 440-256-0514 9019 Kirtland Chardon Road, Kirtland, OH 44094 Recipes Pecan-Crusted Beef Tenderloin with Juniper Jus Two 2 ½ - pound well-trimmed center-cut 1 cup pecans, very finely chopped beef tenderloins, not tied 3 shallots, thinly sliced Salt and freshly ground pepper 1 carrot, thinly sliced 4 tablespoons unsalted butter 1 tablespoon tomato paste 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil 2 teaspoons dried juniper berries, crushed ¼ cup ketchup 1 ½ cups full-bodied red wine, such as Syrah ¼ cup Dijon mustard 1 cup beef demiglace (see Note) 4 large egg yolks Preheat the oven to 425°F. -

ESCMID Online Lecture Library @ by Author Outline

Completing The Endgame Global Polio Eradication ECCMID, April 27, 2015 ESCMID Online Lecture Library @ by author Outline • Progress toward wild poliovirus eradication • Withdrawal of type 2 Oral Polio Vaccine • Managing the long-term risks • Global program priorities in 2015 ESCMID Online Lecture Library @ by author Wild Poliovirus Eradication, 1988-2012 125 Polio Endemic countries 125 Polioto Endemic 3 endemiccountries countries 400 300 19882012 200 Polio cases (thousands) 100 Last type 2 polio in Last Polio Case in the world India 0 ESCMID Online Lecture Library 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 @ by author Beginning of the Endgame Success in India established strategic & scientific feasibility of poliovirus eradication Poliovirus Type 2 eradication raised concerns about continued use of tOPV ESCMID Online Lecture Library @ by author Endgame Plan Objectives , 2013-18 1. Poliovirus detection & interruption 2. OPV2 withdrawal, IPV introduction, immunization system strengthening 3. Facility Containment & Global Certification ESCMID Online Lecture Library 4. Legacy Planning @ by author Vaccine-derived polio outbreaks (cVDPVs) 2000-2014 >90% VDPV cases are type 2 (40% of Vaccine-associated polio is also type 2) Type 1 ESCMID Online LectureType 2Library Type 3 @ by author Justification for new endgame Polio eradication not feasible without removal of all poliovirus strains from populations ESCMID Online Lecture Library @ by author Interrupting Poliovirus Transmission ESCMID Online Lecture Library @ by author Not detected since Nov 2012 ESCMID Online Lecture Library @ by author Wild Poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) Cases, 2013 Country 2013 2014 Pakistan 93 174 Afghanistan 14 10 Nigeria 53 6 Somalia 194 5 Cameroon 4 5 Equatorial Guinea 0 5 Iraq 0 2 Syria 35 1 Endemic countries Infected countries Ethiopia 9 1 Kenya 14 0 ESCMID Online Lecture TotalLibrary 416 209 Israel = Env. -

Transcript of Hajiya Binta Abdulhamid Interviewer: Elisha Renne

GLOBAL FEMINISMS COMPARATIVE CASE STUDIES OF WOMEN’S ACTIVISM AND SCHOLARSHIP SITE: NIGERIA Transcript of Hajiya Binta Abdulhamid Interviewer: Elisha Renne Location: Kano, Nigeria Date: 31st January, 2020 University of Michigan Institute for Research on Women and Gender 1136 Lane Hall Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1290 Tel: (734) 764-9537 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.umich.edu/~glblfem © Regents of the University of Michigan, 2017 Hajiya Binta Abdulhamid was born on March 20, 1965, in Kano, the capital of Kano State, in northern Nigeria. She attended primary school and girls’ secondary school in Kano and Kaduna State. Thereafter she attended classes at Bayero University in Kano, where she received a degree in Islamic Studies. While she initially wanted to be a journalist, in 1983 she was encouraged to take education courses at the tertiary level in order to serve as a principal in girls’ secondary schools in Kano State. While other women had served in this position, there has been no women from Kano State who had done so. She has subsequently worked under the Kano State Ministry of Education, serving as school principal in several girls’ secondary schools in Kano State. Her experiences as a principal and teacher in these schools has enabled her to support girl child education in the state and she has encouraged women students to complete their secondary school education and to continue on to postgraduate education. She sees herself as a woman-activist in her advocacy of women’s education and has been gratified to see many of her former students working as medical doctors, lawyers, and politicians. -

Societal Responses to the State of Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) in Kano

Societal Responses to the State of Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) in Kano Metropolis- Nigeria A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Mustapha Hashim Kurfi June 2010 © 2010 Mustapha Hashim Kurfi. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Societal Responses to the State of Orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) in Kano Metropolis- Nigeria by MUSTAPHA HASHIM KURFI has been approved for the Center for International Studies by Steve Howard Professor of African Studies Steve Howard Director, African Studies Daniel Weiner Executive Director, Center for International Studies 3 ABSTRACT KURFI, MUSTAPHA HASHIM, M.A., June 2010, African Studies Societal Responses to the State of Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) in Kano Metropolis- Nigeria (131 pp.) Director of Thesis: Steve Howard This study uses qualitative methodology to examine the contributions of Non- Governmental Organizations in response to the conditions of Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) in Kano metropolis. The study investigates what these organizations do, what methods, techniques, and strategies they employ to identify the causes of OVC’s conditions for intervention. The study acknowledges colonization, globalization, poverty, illiteracy, and individualism as contributing factors to OVC’s conditions. However, essentially, the study identifies gross misunderstanding between paternal and maternal relatives of children to be the main factor responsible for the OVC’s conditions. This social disorganization puts the children in difficult conditions including exposure to health, educational, moral, emotional, psychological, and social problems. The thesis concludes that through “collective efficacy” the studied organizations are a perfect means for solving-problem. -

Big Game Hunting Practices, Meanings, Motivations And

BIG GAME HUNTING PRACTICES, MEANINGS, MOTIVATIONS, AND CONSTRAINTS: A SURVEY OF OREGON BIG GAME HUNTERS Suresh K. Shrestha, Ph.D. (Brown 2009, Brown et al. 2000) and many wildlife Recreation, Parks and Tourism Resources conservation programs are funded through the sales of West Virginia University hunting licenses (Anderson et al. 1985, Floyd and Lee [email protected] 2002). Robert C. Burns The trend data, however, indicate that the participation West Virginia University of Americans in hunting has been declining over the past decade (USDI and USDC 2006). Similar downward trends have been noted in the number of Abstract.—We conducted a self-administered mail days spent in general hunting and big game hunting, survey in September 2009 with randomly selected and in hunters’ expenditures. Considering the Oregon hunters who had purchased big game hunting dependence of wildlife managers on regulated hunting licenses/tags for the 2008 hunting season. Survey to manage populations of game species as well as pest questions explored hunting practices, the meanings wildlife species, a decline in the number of hunters of and motivations for big game hunting, the will have tremendous direct and indirect managerial, constraints to big game hunting participation, and the social, economic, and environmental implications effects of age, years of hunting experience, hunting (Anderson et al. 1985, Floyd and Lee 2002, Lauber motivations, hunting meanings, and hunting success and Brown 2000, Sun et al. 2005). on overall quality of experience. The study found that although hunters gave high scores to the emotional The situation in the Pacific Northwest, including the and traditional meanings of hunting, their quality of state of Oregon, is even worse with respect to hunting experience depended largely on hunting success. -

Status and Development of Old-Growth Elements and Biodiversity During Secondary Succession of Unmanaged Temperate Forests

Status and development of old-growth elementsand biodiversity of old-growth and development Status during secondary succession of unmanaged temperate forests temperate unmanaged of succession secondary during Status and development of old-growth elements and biodiversity during secondary succession of unmanaged temperate forests Kris Vandekerkhove RESEARCH INSTITUTE NATURE AND FOREST Herman Teirlinckgebouw Havenlaan 88 bus 73 1000 Brussel RESEARCH INSTITUTE INBO.be NATURE AND FOREST Doctoraat KrisVDK.indd 1 29/08/2019 13:59 Auteurs: Vandekerkhove Kris Promotor: Prof. dr. ir. Kris Verheyen, Universiteit Gent, Faculteit Bio-ingenieurswetenschappen, Vakgroep Omgeving, Labo voor Bos en Natuur (ForNaLab) Uitgever: Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek Herman Teirlinckgebouw Havenlaan 88 bus 73 1000 Brussel Het INBO is het onafhankelijk onderzoeksinstituut van de Vlaamse overheid dat via toegepast wetenschappelijk onderzoek, data- en kennisontsluiting het biodiversiteits-beleid en -beheer onderbouwt en evalueert. e-mail: [email protected] Wijze van citeren: Vandekerkhove, K. (2019). Status and development of old-growth elements and biodiversity during secondary succession of unmanaged temperate forests. Doctoraatsscriptie 2019(1). Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek, Brussel. D/2019/3241/257 Doctoraatsscriptie 2019(1). ISBN: 978-90-403-0407-1 DOI: doi.org/10.21436/inbot.16854921 Verantwoordelijke uitgever: Maurice Hoffmann Foto cover: Grote hoeveelheden zwaar dood hout en monumentale bomen in het bosreservaat Joseph Zwaenepoel