University Student Strategies to Cope with Anxiety in Learning English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Seventh-Day Adventist Colleges and Universities

DIRECTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ADVENTIST ACCREDITING ASSOCIATION Accrediting Association of Seventh-day Adventist Schools, Colleges, and Universities 12501 Old Columbia Pike, Silver Spring, Maryland 20904 USA 2018-2019 CONTENTS Preface 5 Board of Directors 6 Adventist Colleges and Universities Listed by Country 7 Adventist Education World Statistics 9 Adriatic Union College 10 AdventHealth University 11 Adventist College of Nursing and Health Sciences 13 Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies 14 Adventist University Cosendai 16 Adventist University Institute of Venezuela 17 Adventist University of Africa 18 Adventist University of Central Africa 20 Adventist University of Congo 22 Adventist University of France 23 Adventist University of Goma 25 Adventist University of Haiti 27 Adventist University of Lukanga 29 Adventist University of the Philippines 31 Adventist University of West Africa 34 Adventist University Zurcher 36 Adventus University Cernica 38 Amazonia Adventist College 40 Andrews University 41 Angola Adventist Universitya 45 Antillean Adventist University 46 Asia-Pacific International University 48 Avondale University College 50 Babcock University 52 Bahia Adventist College 55 Bangladesh Adventist Seminary and College 56 Belgrade Theological Seminary 58 Bogenhofen Seminary 59 Bolivia Adventist University 61 Brazil Adventist University (Campus 1, 2 and 3) 63 Bugema University 66 Burman University 68 Central American Adventist University 70 Central Philippine Adventist College 73 Chile -

SKOLASTIK Study Was to Determine the Relationship Between Burnout and Complaints of KEPERAWATAN Musculoskeletal Pain in Nurses at the Klabat University

HUBUNGAN BURNOUT DAN KELUHAN NYERI MUSKULOSKELETAL PADA MAHASISWA PROFESI NERS DI UNIVERSITAS KLABAT RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BURNOUT AND MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN ON NERS STUDENT AT UNIVERSITAS KLABAT James Richard Maramis1 Claudia Priscilla Kandowangko2 Fakultas Ilmu Keperawatan, Universitas Klabat, Manado, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRAK Pendahuluan: Mahasiswa keperawatan rentan mengalami keadaan lelah baik emosional, psikologi dan fisik yang dirasakan akibat melakukan aktivitas ataupun tuntutan praktik yang dilakukan secara berulang-ulang dan dalam waktu yang lama. Keluhan nyeri muskuloskeletal merupakan salah satu gejala yang terjadi pada gangguan musculoskeletal (MSDs). Tujuan: Tujuan penelitian adalah mengetahui hubungan antara burnout dan keluhan nyeri musculoskeletal pada mahasiswa profesi ners di Universitas Klabat. Metode: Metode penelitian yang digunakan ialah deskriptif correlation dengan menggunakan pendekatan cross sectional study dan pengambilan sampel dalam penelitan ini adalah menggunakan teknik purposive sampling. Pengumpulan data menggunakan kuesioner burnout dengan kuesioner Nordic Body Map yang diberikan kepada 127 mahasiswa profesi ners di Universitas Klabat dan data dianalisis dengan menggunakan uji Spearman's rho. Hasil: Didapati pada umumnya mahasiswa sebanyak 109 orang (85,8%) memiliki tingkat burnout sedang, dan 100 mahasiswa (78,7%) merasakan keluhan musculoskeletal ringan. Daerah tubuh yang paling banyak dikeluhkan ialah di punggung dengan jumlah nilai sebanyak 273 Sedangkan hasil uji statistic antara burnout dengan keluhan nyeri musculoskeletal menunjukkan nilai p=0,000<0,05, dengan demikian ada hubungan antara burnout dengan keluhan nyeri musculoskeletal. Nilai r=0,337 yang menunjukkan arah korelasi positif antara dua variabel atau searah. Diskusi: Peneliti selanjutnya dapat meneliti pengaruh rutinitas kegiatan tertentu dan postur tubuh yang dilakukan oleh perawat ketika bekerja terhadap keluhan MSD-nya, dan juga agar mencari tahu hubungannya dengan keluhan-keluhan MSD yang dirasakan responden lebih dari tujuh hari. -

World Higher Education Database Whed Iau Unesco

WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO Página 1 de 438 WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO Education Worldwide // Published by UNESCO "UNION NACIONAL DE EDUCACION SUPERIOR CONTINUA ORGANIZADA" "NATIONAL UNION OF CONTINUOUS ORGANIZED HIGHER EDUCATION" IAU International Alliance of Universities // International Handbook of Universities © UNESCO UNION NACIONAL DE EDUCACION SUPERIOR CONTINUA ORGANIZADA 2017 www.unesco.vg No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted without written permission. While every care has been taken in compiling the information contained in this publication, neither the publishers nor the editor can accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions therein. Edited by the UNESCO Information Centre on Higher Education, International Alliance of Universities Division [email protected] Director: Prof. Daniel Odin (Ph.D.) Manager, Reference Publications: Jeremié Anotoine 90 Main Street, P.O. Box 3099 Road Town, Tortola // British Virgin Islands Published 2017 by UNESCO CENTRE and Companies and representatives throughout the world. Contains the names of all Universities and University level institutions, as provided to IAU (International Alliance of Universities Division [email protected] ) by National authorities and competent bodies from 196 countries around the world. The list contains over 18.000 University level institutions from 196 countries and territories. Página 2 de 438 WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO World Higher Education Database Division [email protected] -

World Report 2019 Adventist Education Around the World

World Report 2019 Adventist Education Around the World General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists Department of Education December 31, 2019 Table of Contents World Reports ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 List of Acronyms and Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 List of Basic School Type Definitions ...................................................................................................................................................................... 7 World Summary of Schools, Teachers, and Students ............................................................................................................................................. 8 World Summary of School Statistics....................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Division Reports ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 10 East-Central Africa Division (ECD) ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Servant Leadership, Sacrificial Service

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE FOR COLLEGE & UNIVERSITY PRESIDENTS Servant Leadership, Sacrificial Service March 24-27, 2014 Washington DC General Conference Department of Education AEO-PresidentsConferenceProgram.indd 1 3/19/14 2:24 PM Monday March 24, 2014 Time Presentation/Activity Presenter/Responsible Venue 16:30-18:00 Arrival, Registration Education Department GC Lobby 18:00-19:00 Welcome Reception Education Department GC Atrium 19:00-20:00 Showcase Divisions Auditorium Those requiring translation to Spanish, Portuguese or Russian may check out a radio at registration. Tuesday March 25, 2014 Time Presentation/Activity Presenter/Responsible Venue Dick Barron 08:00 – 09:00 Week of Prayer Auditorium Prayer: Stephen Currow 09:00 – 09:30 Welcome and Introductions Lisa Beardsley-Hardy Auditorium George R. Knight 09:30 – 10:30 Philosophy of Adventist Education Auditorium Coordinator: Lisa Beardsley-Hardy 10:30 – 10:45 Break Auditorium Ted Wilson 10:45 – 11:45 Role of Education in Church Mission Auditorium Coordinator: Ella Simmons 11:45 – 13:00 Lunch All GC Cafeteria Humberto Rasi 13:00 – 14:00 Trends in Adventist Education Auditorium Coordinator: John Fowler Gordon Bietz 14:00 – 15:15 Biblical Foundations of Servant Leadership Auditorium Coordinator: John Wesley Taylor V Panel: Susana Schulz, Norman Knight *14:00 – 15:15 Role of President’s Spouse 2 I-18 Demetra Andreasen, & Yetunde Makinde 15:15 – 15:30 Break Auditorium Panel, Discussion: Niels-Erik Andreasen, 15:30 – 16:30 Experiences and Expectations Juan Choque, Sang Lae Kim, Stephen Guptill, -

The Effectiveness of Information Technology As a Learning Media Towards Teaching Role (Case Study for Student Due to Pandemic Covid-19)

The Effectiveness of Information Technology as a Learning Media towards Teaching Role (Case Study for Student due to Pandemic Covid-19) 1st Zaharah 2nd Indrayanto 3rd Cut Dhien Nourwahidah Department of Social Sciences Department of Social Sciences Department of Social Sciences Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic State Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic State Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic State University University University Jakarta, Indonesia Jakarta, Indonesia Jakarta, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 6th Kamarusdiana 4th Akhmad Saehudin 5th Hamka Hasan Departement of Family Law Departement of Translation Departement of Islamic Studies Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic State Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic State Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic State University University University Jakarta, Indonesia Jakarta, Indonesia Jakarta, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract— Learning system Electronic or online learning is selection, transformation, and distribution of all types of a policy implemented by the government during this pandemic. information. The Ministry of Education of the Republic of Indonesia has issued a Circular of the Minister of Education and Culture More simply, [2] summarizes the nature of information Number: 36962 / MPK.A / HK / 2020 regarding Online Learning and communication technology as technology related to and Working from Home in the Context of Preventing the information retrieval, collection, processing, storage, Spread of Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19). The emergence of dissemination, and presentation. This term appears after a distance or online learning can anticipate the role of teachers as combination of computer technology (including hardware and teachers and educators. This research was conducted on software) and communication technology. -

Laporan Tahunan

2012 annual report PT BANK INDEX SELINDO Daftar Isi Visi, Misi dan Nilai Perusahaan Content Vision, Mission and Company Values i Visi & Misi Vision & Mision 01 Ikhtisar Keuangan VisiVision Financial Highlights Menjadi Bank Retail Yang Sehat, Kuat dan Terpercaya Untuk 02 Sambutan Presiden Komisaris Memberikan Dukungan Terbaik Dalam Membangun Perekonomian Message from the President Commissioner Bangsa. 06 Sambutan Presiden Direktur To be a financially sound, strong and reliable retail bank committed to Message from the President Director developing the national economy. 10 Ikhtisar Peristiwa 2012 Events and Activities Highlights in 2012 12 Kinerja Keuangan Financial Performance 18 Tata Kelola Perusahaan Corporate Governance MisiMission 26 Pengelolaan Risiko Memberikan Dukungan Terbaik Bagi Usaha Anda. Risk Management To provide the best support for your business. 40 Kebijakan Manajemen dan Strategi Management’s Policy and Strategy Dukungan yang diberikan kepada nasabah diimplementasikan melalui 3 (tiga) panduan dasar operasional yang meliputi: 44 Laporan Manajemen Management Report • Selalu mengutamakan kualitas layanan kepada nasabah. • Selalu menjunjung nilai-nilai kejujuran, etika dan integritas. 57 Informasi Perusahaan • Selalu mengedepankan pendekatan yang lebih personal dan tulus. Corporate Information The support for customers is implemented through 3 (three) basic 74 Tanggung Jawab Pelaporan Keuangan operating guidelines, covering: Responsibility for Financial Reporting • Always prioritize quality when providing services to customers. -

List of English and Native Language Names

LIST OF ENGLISH AND NATIVE LANGUAGE NAMES ALBANIA ALGERIA (continued) Name in English Native language name Name in English Native language name University of Arts Universiteti i Arteve Abdelhamid Mehri University Université Abdelhamid Mehri University of New York at Universiteti i New York-ut në of Constantine 2 Constantine 2 Tirana Tiranë Abdellah Arbaoui National Ecole nationale supérieure Aldent University Universiteti Aldent School of Hydraulic d’Hydraulique Abdellah Arbaoui Aleksandër Moisiu University Universiteti Aleksandër Moisiu i Engineering of Durres Durrësit Abderahmane Mira University Université Abderrahmane Mira de Aleksandër Xhuvani University Universiteti i Elbasanit of Béjaïa Béjaïa of Elbasan Aleksandër Xhuvani Abou Elkacem Sa^adallah Université Abou Elkacem ^ ’ Agricultural University of Universiteti Bujqësor i Tiranës University of Algiers 2 Saadallah d Alger 2 Tirana Advanced School of Commerce Ecole supérieure de Commerce Epoka University Universiteti Epoka Ahmed Ben Bella University of Université Ahmed Ben Bella ’ European University in Tirana Universiteti Europian i Tiranës Oran 1 d Oran 1 “Luigj Gurakuqi” University of Universiteti i Shkodrës ‘Luigj Ahmed Ben Yahia El Centre Universitaire Ahmed Ben Shkodra Gurakuqi’ Wancharissi University Centre Yahia El Wancharissi de of Tissemsilt Tissemsilt Tirana University of Sport Universiteti i Sporteve të Tiranës Ahmed Draya University of Université Ahmed Draïa d’Adrar University of Tirana Universiteti i Tiranës Adrar University of Vlora ‘Ismail Universiteti i Vlorës ‘Ismail -

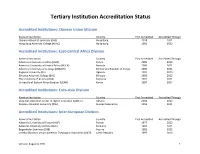

Tertiary Institution Accreditation Status

Tertiary Institution Accreditation Status Accredited Institutions: Chinese Union Mission Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Chinese Adventist Seminary (CAS) Hong Kong 2018 2021 Hong Kong Adventist College (HKAC) Hong Kong 1982 2022 Accredited Institutions: East-Central Africa Division Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Adventist University of Africa (AUA) Kenya 2005 2022 Adventist University of Central Africa (AUCA) Rwanda 2006 2021 Adventist University of Lukanga (UNILUK) Democratic Republic of Congo 2005 2021 Bugema University (BU) Uganda 1992 2023 Ethiopia Adventist College (EAC) Ethiopia 1993 2022 The University of Arusha (UOA) Tanzania 1992 2021 University of Eastern Africa Baraton (UEAB) Kenya 1987 2024 Accredited Institutions: Euro-Asia Division Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Ukrainian Adventist Center of Higher Education (UACHE) Ukraine 2004 2024 Zaoksky Adventist University (ZAU) Russian Federation 1994 2021 Accredited Institutions: Inter-European Division Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Adventist University of France (AUF) France 1977 2022 Adventus University Cernica (AUC) Romania 1997 2021 Bogenhofen Seminary (SSB) Austria 1983 2022 Czecho-Slovakian Union Adventist Theological Institute (CSUATI) Czech Republic 1997 2024 Version: August 4, 2021 1 Listing of Seventh-day Adventist Colleges and Universities, continued Friedensau Adventist University (FAU) Germany 1984 2021 Italian Adventist University Villa -

Easychair Preprint Risk Factors of Pulmonary Tuberculosis Incidence in DOTS Polyclinics of Prof. R. D. Kandou Manado Hospital

EasyChair Preprint № 3973 Risk Factors of Pulmonary Tuberculosis Incidence in DOTS Polyclinics of Prof. R. D. Kandou Manado Hospital Rivaldo Misa and Metty Wuisang EasyChair preprints are intended for rapid dissemination of research results and are integrated with the rest of EasyChair. July 30, 2020 Nutrix Journal 1 RISK FACTORS OF PULMONARY TUBERCULOSIS INCIDENCE IN DOTS POLYCLINIC OF PROF DR. R. D. KANDOU MANADO HOSPITAL Rivaldo Dave Misa1, Metty Wuisang2 1.Departement of Nursing Fundamental, Faculty of Nursing, Klabat University, JL Arnold Mononutu , Airmadidi, 95371, Indonesia 2. Lecture in the Faculty of Nursing, Klabat University JL Arnold Mononutu, Airmadidi, 95371, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. These germs infect the lungs more often but can also attack other organs of the body. The purpose of the study was to determine the description of risk factors for pulmonary TB patients in the DOTS Polyclinic Prof. R. D. Kandou Manado. This type of research is quantitative descriptive through a cross sectional approach with 32 respondents. The results obtained are pulmonary TB sufferers who have a contact history of 6 respondents (18.8%) and pulmonary TB sufferers who do not have a contact history of 26 respondents (81.3%), who have completed elementary school totaling 2 respondents (6.3%), graduated junior high numbered 5 respondents (15.6%), graduated high school totaling 22 respondents (68.8%), and those who graduated from college totaled 3 respondents (9.4%), male totaled 21 respondents (65%) and female totaling 11 respondents (34%), those who have enough knowledge amounted to 16 respondents (50%) and good knowledge amounted to 16 respondents (50%), who were smoking amounted to 17 respondents (53.1%), did not smoke amounted to 13 respondents (40.6%), and who ever smoked amounted to 2 respondents (6.3%). -

Post-Secondary Institutions

AAA Accreditation Status for Colleges and Universities The following list identifies by Division and Country all post-secondary institutions recognized and accredited by the Accrediting Association of Seventh-day Adventist Schools, Colleges, and Universities (AAA) along with the year each institution was first accredited and when current accreditation expires. Expiration is always on December 31 of the year identified, and during that same year an accreditation visit will be scheduled. The following definitions apply: ▪ Accredited: An institution with full accreditation. ▪ Mid-Level Training Institutions: Institutions that offer education which goes beyond secondary level education but is less than a bachelor’s degree. These include diploma teacher training, technical training in building and construction or other professional trades, and non-collegiate hospital-based schools of nursing (c.f. FE 30 15). ▪ In Candidacy: An institution in the process of application for full accreditation. Programs are still recommended for transfer to other accredited institutions. The maximum candidacy term is two years. ▪ In Pre-candidacy: An institution that has met basic criteria for operation and is working towards candidacy status. Programs are not yet recognized for transfer to other accredited institutions. The maximum pre-candidacy term is 5 years. ▪ On Probation: An institution that has held full accreditation but is not presently meeting accreditation expectations in certain critical areas. After a set period, accreditation will either be revoked -

TOSU-Intl-Grad-Processing-Manual

The Ohio State University Graduate, International Admissions Office Argentina Minimum requirement for admission into an OSU master’s degree program (Completion of 16 years of study) • Licenciado – awarded after completion of 5 years of post-secondary study. • Odontologo (Dentist) – awarded after completion of 5 years of post-secondary study. First professional degree in dentistry. • Ingeniero (Engineer), Veterinario (Veterinarian), Abogado (Lawyer) – awarded after completion of 5 to 6 years of post-secondary study. First professional degree in respective field. • Arquitecto (Architect) – awarded after completion of 6 years of post-secondary study. First professional degree in architecture. • Medico (Doctor) – awarded after completion of 6 to 7 years of post-secondary study. First professional degree in medicine. Minimum requirement for admission into an OSU graduate program with eligibility to receive 45 hours of transfer credit Official credentials are issued in the original language. for master’s degree Certified, word-for-word English translations must accompany (Completion of 18 years of study) each credential not issued in English. • Magister, Maestría, Magister Scientiae – awarded after completion of 2 years of post-graduate study Common Grading Systems following a first degree. This scale is used as a default when a grade scale is not provided on the transcript. If a grade scale is provided on a OSU Benchmark of an equivalent of a U.S. Ph.D. transcript, that scale is used in determining the GPA. • Doctorado – awarded after completion of – awarded after completion of 2 to 6 years of post-graduate study Grade 10 pt scale Description OSU Equiv. following a first degree. Sobresaliente 9.0 – 10 Excellent A Distinguido 7.0 – 8.9 Very Good B+ Additional Information Bueno 5.0 – 6.9 Good B Higher education is provided by national and private universities, teacher Aprobado 4.0 – 4.9 Passing C training institutes and institutions devoted to fine arts, technical and Insuficiente 2.0 – 3.0 Insufficient D professional studies.