University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Trends Report Q2 2019

1 VIDEO TRENDS REPORT Q2 2019 © 2019 TiVo Corporation. Introduction 2 Survey Methodology Q2 2019 Survey Size INTRODUCTION 5,340 Geographic Regions U.S., Canada TiVo seeks real consumer opinions to uncover key trends relevant to TV providers, digital publishers, advertisers and consumer electronics manufacturers for our survey, which is administered quarterly and examined biannually in this Age of Respondents published report. We share genuine, unbiased perspectives and feedback from viewers to give video service providers 18+ and industry stakeholders insights for improving and enhancing the overall TV-viewing experience for consumers. TiVo has conducted a quarterly consumer survey since 2012, enabling us to monitor, track and identify key trends in viewing This survey was conducted in Q2 2019 by a leading habits, in addition to compiling opinions about video providers, emerging technologies, connected devices, OTT apps and third-party survey service; TiVo analyzed the results. content discovery features, including personalized recommendations and search. TiVo conducts this survey on a quarterly basis and publishes a biannual report evaluating and analyzing TiVo (NASDAQ: TIVO) brings entertainment together, making it easy to find, watch and enjoy. We serve up the best key trends across the TV industry. movies, shows and videos from across live TV, on-demand, streaming services and countless apps, helping people to watch on their terms. For studios, networks and advertisers, TiVo delivers a passionate group of watchers to increase viewership and engagement across all screens. Go to tivo.com and enjoy watching. For more information about TiVo’s solutions for the media and entertainment industry, visit business.tivo.com or follow us on Twitter @tivoforbusiness. -

Montreal, Québec

st BOOK BY BOOK BY DECEMBER 31 DECEMBER 31st AND SAVE $200 PER COUPLE AND SAVE $200 PER COUPLE RESERVATION FORM: (Please Print) TOUR CODE: 18NAL0629/UArizona Enclosed is my deposit for $ ______________ ($500 per person) to hold __________ place(s) on the Montreal Jazz Fest Excursion departing on June 29, 2018. Cost is $2,595 per person, based on double occupancy. (Currently, subject to change) Final payment due date is March 26, 2018. All final payments are required to be made by check or money order only. I would like to charge my deposit to my credit card: oMasterCard oVisa oDiscover oAmerican Express Name on Card _____________________________________________________________________________ Card Number ______________________________________________ EXP_______________CVN_________ NAME (as it appears on passport): o Mr. o Mrs. o Ms.______________________________________ Date of Birth (M/D/Y) _______/_______/________ NAME (as it appears on passport): o Mr. o Mrs. o Ms.______________________________________ Date of Birth (M/D/Y) _______/_______/________ NAME FOR NAME BADGE IF DIFFERENT FROM ABOVE: 1)____________________________________ 2)_____________________________________ STREET ADDRESS: ____________________________________________________________________ CITY:_______________________________________STATE:_____________ZIP:___________________ PHONE NUMBERS: HOME: ( )______________________ OFFICE: ( )_____________________ 1111 N. Cherry Avenue AZ 85721 Tucson, PHOTO CREDITS: Classic Escapes; © Festival International de Jazz de Montréal; -

The Tennessee -& Magazine

Ansearchin ' News, vol. 47, NO. 4 Winter zooo (( / - THE TENNESSEE -& MAGAZINE THE TENNESSEE GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY 9114 Davies Pfmrauon Road on rhe h~srorkDa vies Pfanrarion Mailng Addess: P. O, BOX247, BrunswrCG, 737 38014-0247 Tefephone: (901) 381-1447 & BOARD MEMBERS President JAMES E. BOBO Vice President BOB DUNAGAN Contributions of all types of Temessee-related genealogical Editor DOROTEíY M. ROBERSON materials, including previously unpublished famiiy Bibles, Librarian LORElTA BAILEY diaries, journals, letters, old maps, church minutes or Treasurer FRANK PAESSLER histories, cemetery information, family histories, and other Business h4anager JOHN WOODS documents are welcome. Contributors shouid send Recording Secretary RUTH REED photocopies of printed materials or duplicates of photos Corresponding Secretary BEmHUGHES since they cannot be returned. Manuscripts are subject Director of Sales DOUG GORDON to editing for style and space requirements, and the con- Director of Certiñcates JANE PAESSLER tributofs narne and address wiU & noted in the publish- Director at Large MARY ANN BELL ed article. Please inciude footnotes in the article submitted Director at Large SANDRA AUSTIN and list additional sources. Check magazine for style to be used. Manuscripts or other editorial contributions should be EDITO-. Charles and Jane Paessler, Estelle typed or printed and sent to Editor Dorothy Roberson, 7 150 McDaniel, Caro1 Mittag, Jeandexander West, Ruth Reed, Belsfield Rd., Memphis, TN 38 119-2600. Kay Dawson Michael Ann Bogle, Kay Dawson, Winnie Calloway, Ann Fain, Jean Fitts, Willie Mae Gary, Jean Giiiespie, Barbara Hookings, Joan Hoyt, Thurman Members can obtain information fiom this file by writing Jackson, Ruth O' Donneii, Ruth Reed, Betty Ross, Jean TGS. -

Industrial Market Turns the Corner Special Coverage on Industrial Sector’S Recovery, Office Market’S Struggles

March 31-April 6, 2012, Vol. 5, Issue 14 SPECIAL EMPHASIS: OFFICE & INDUSTRIAL REAL ESTATE INDUSTRIAL MARKET TURNS THE CORNER Special coverage on industrial sector’s recovery, office market’s struggles PAGE 16 TOWERING QUESTIONS Businesses seek answers as health care reform looms PAGE 26 Bill Courtney and the Manassas football team have the nation cheering. Illustration: Emily Morrow 28 Sports On a nightly basis it’s hard to predict which member of the Memphis Grizzlies will be the hero, but the chameleon approach is working for the team. WEEKLY DIGEST: PAGE 2 FINANCIAL SERVICES: PAGE 8 real EState: PAGES 30-31 artS AND FOOD: PAGES 38-39 EDITORIAL: PAGE 42 A Publication of The Daily News Publishing Co. | www.thememphisnews.com 2 March 31-April 6, 2012 www.thememphisnews.com weekly digest Get news daily from The Daily News, www.memphisdailynews.com. EEOC Accuses AutoZone Prudential’s Ware Receives Of Disability Discrimination Corporate Services Award A federal agency is accusing Memphis- Angie Ware of Prudential Collins-Maury based auto-parts retailer AutoZone Inc. of Inc. Realtors was honored with the 2011 illegally firing an employee because of her North American Corporate Services/Relo- disability. cation Director of the Year Award at Pruden- The U.S. Equal Employment Oppor- tial Real Estate’s recent sales convention. tunity Commission filed a federal lawsuit The honor is awarded for outstand- against AutoZone this week. ing facilitation of new corporate business The EEOC says the company fired a development and consistent service excel- manager in its Cudahy store in 2009. The lence in relocation and referral operations, agency says the woman had just received as well as participation in activities contrib- a doctor’s clearance to return to work with uting to network excellence. -

Rivevideo Distribution-Sample List Urban Hip Hop Video Shows

FEATURED DESTINATIONS & OUTLETS MTV is an American network based in New York City that launched August 1, 1981. MTV has had a profound impact on the music industry and pop culture around the globe. Broadcast to more than 750 college campuses and via top cable distributors in 700 college communities nationwide, mtvU reaches upwards of 9 million U.S. college students – making it the largest, most comprehensive television network just for college students. Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, mtvU can be seen in the dining areas, fitness centers, student lounges and dorm rooms of campuses throughout the U.S., as well as on cable programming. MTV Live (formerly Palladia) is a high definition channel that showcases the biggest music videos, live concerts, performances, festivals, documentaries and more from all the artists you love. MTV LIVE has created a truly enhanced musical experience - the sense that you are there, and can touch and feel the music. Featuring stellar Dolby 5.1 Surround Sound and a high-grade picture, MTV Live is your personal in-home all-access pass to concerts, festivals, performances, music videos, documentaries, and more 24/7. MTV offers broadband Video On Demand which acts an interactive add-on to the network's broadcast content, with music videos, extra scenes, highlights packages, news roundups, movie trailers and more. MTV Tr3s is a cable, satellite and over-the-air network which is broadcasted to over 40 million households spanning the US & South America. It is rooted in the fusion of Latin America and American music, cultures, and languages, bringing the biggest names of Latin artist in pop, urban, and rock music. -

The Tennessee Magazine

Ansearchin ' News, VOI.46, NO.3 Fa11 1999 rT THE TENNESSEE MAGAZINE THE TENNESSEE GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY 91 14 Davies Plantation Road on the histonc Davies Plantation Mailing Address: P. 0.Box 247, Brunswick, W38014-0247 Telephone: (901) 381-1447 5 OFFICER$ & BOARD MEMBES TGS Librarian Nelson Dickey ident JAMES E. BOB0 .or DOROTHY M. ROBERSON Dies After Extended Illness ing Librarian LORETTA BAILEY Nelson Dickey, librarian of the Tennessee Genealogical asurer FRANK PAESSLER Society for the past five years, died 23 June 1999 at a Mem- iness Manager JOHN WOODS phis hospital following an extended illness. He was 67. ording Secretary JO B. SMITH, Born 9 Oct 1931 in Jackson, Tenn., he was the son of responding Secretary SUE McDERMOTT George Hervey Dickey and Mayrne Huber Chumber of Milan. nbership Chairman SANDRA AUSTIN On 19 June 1957, Nelson rnanied Gladys Ann Ross in Milan. %tor of Sales DOUG GORDON They later moved to the Memphis area where he was vice :ctor of Certificates JANE PAESSLER president of Atlas Contractors, Inc. He was a Navy veteran ector at Large MARY ANN BELL of the Korean War, a member of the Germantown United Methodist Church choir, a Mason, Shriner, and member of ector at Large BETTY HUGHES ector of Surname Index JEAN CRAWFORD the Sons of the American Revolution. Nelson is survived by his wife; two daughters, Dara ector of Surname Index MARILYN VAN EYNDE Fields Dickey and Dawne Dickey Davis, both of Leesburg, Va.; and two grandchildren. Graveside rites were held at : Charles and Jane Paessler, Estelle Oakwood Cemetery in Milan on 24 June, and memorial Daniel. -

Sons of the American Revolution. Continental Chapter Records MSS.194

Sons of the American Revolution. Continental Chapter records MSS.194 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 26, 2013 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Ball State University Archives and Special Collections Alexander M. Bracken Library 2000 W. University Avenue Muncie, Indiana, 47306 765-285-5078 [email protected] Sons of the American Revolution. Continental Chapter records MSS.1 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 Series 1: Continental Chapter, 1922-2007............................................................................................. -

NEW FRANCE Forging a Nation

Chapter One NEW FRANCE Forging a Nation This chapter sets the scene for the founding Cabot’s reports of an abundant fishery and development of New France and gives gave rise to fishing by the English commenc- readers an understanding of how early ex- ing in 1498. They were soon joined by the plorers and the first colonists fostered the Portuguese, the French from Normandy and development of our country. A second ob- Brittany, and later the French and Spanish jective is to identify our ancestors who were Basques. The Newfoundland fishery became the first of their generation to immigrate to an important source for home needs and 1 New France, mostly in the 17th century. other European markets. For those who wish to delve further into Whaling in the St. Lawrence Gulf and es- early Quebec history, the bibliography in- tuary and Strait of Belle Isle was also an im- cludes several excellent works. portant source of meat, blubber and oil for In the early 1500s, France was the domi- lamps. Basque whalers were the dominant nant force in Europe. It had the largest pop- group and active there for two centuries, ulation, a strong ruling class and governing catching beluga whales and operating on- structure, the largest army, and a powerful shore settlements for processing at several church with an organized missionary vision. locations on the coasts of Newfoundland Yet, despite its position of strength, France and Labrador and the north shore of the St. was overshadowed by Spain, Portugal, Eng- Lawrence River. land and Holland in the development of in- Cabot’s discovery of Newfoundland led to ternational trade and formation of New further exploration and settlement. -

The African American Experience in the City of Memphis, 1860-1870

THE AFRICAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE IN THE CITY OF MEMPHIS, 1860-1870 by Nicholas Joseph Kovach A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Major: History The University of Memphis May 2012 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Ronald Joseph Kovach, my mother, Linda Marie Ireland, and my niece, Emily Elizabeth Hilkert. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Arwin Smallwood, for his guidance, patience, and support. Without him, this thesis could truly not have been written. I would also like to thank Dr. Aram Goudsouzian and Dr. Charles Crawford for their valuable insight and support. Finally, I would like to give a special thanks to Dr. Richard Rupp for the initial spark that inspired me to become a historian. iii ABSTRACT Kovach, Nicholas Joseph. M.A. The University of Memphis. May 2012. The African American Experience in Memphis, 1860-1870. Major Professor: Dr. Smallwood. This is a study of African Americans in Memphis, Tennessee. The primary focus is on the transition from slavery to freedom, 1860-1870, and how the changing social structure affected and was influenced by African American agency. City, county, federal and state records were used. Specifically, the Memphis Public Library, University of Memphis Special Collections, and Shelby County Archives served as sources of information. Additionally, a comprehensive bibliography of secondary sources was examined and utilized. Unique conditions existed in Memphis. Since its founding, extremely oppressive conditions existed for slaves and free people of color, which created a resonating struggle for the African American community. -

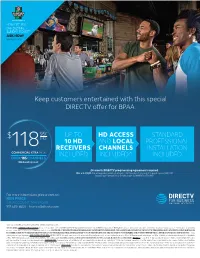

DIRECTV Sell Sheet

NOW GET 35% OFF 2021 NFL SUNDAY TICKET† ASK HOW! WITH SELECT PKGS. Keep customers entertained with this special DIRECTV offer for BPAA. 99* UP TO HD ACCESS STANDARD $ MO. 10 HD AND LOCAL PROFESSIONAL 118 RECEIVERS CHANNELS INSTALLATION COMMERCIAL XTRA PACK INCLUDED INCLUDED^ INCLUDED OVER 185 CHANNELS With 24-month agreement. 24-month DIRECTV programming agreement required. Offer ends 4/30/22. New and upgrading commercial customers only. Pricing based on Estimated Viewing Occupancy (EVO) 1-100. Regional Sports Network Fee of $3.99/mo applies to COMMERCIAL XTRA PACK. For more information, please contact: KEN PRICE SR. ACCOUNT MANAGER 917-689-8600 | [email protected] ^Local channels eligibility based on service address. Not all networks available in all markets. Offer ends 4/30/22. COMMERCIAL XTRA PACK OFFER: Purchase of 24 consecutive months of COMMERCIAL XTRA PACK (regularly $189.99/mo.) required. Upon DIRECTV System activation, DIRECTV will bill the new customer’s account the discounted rate of 32% off the national retail rate, equaling $118.99/mo., with a maximum yearly increase of no more than 5%. TV Access fee of $8/mo. applies to the 3 receiver. IF BY THE END OF THE CONTRACTED PERIOD CUSTOMER DOES NOT CONTACT DIRECTV TO CHANGE SERVICE, THEN ALL SERVICES WILL AUTOMATICALLY CONTINUE AT THE THEN-PREVAILING RATES. IN THE EVENT YOU FAIL TO MAINTAIN YOUR PROGRAMMING AGREEMENT, YOU AGREE THAT DIRECTV MAY CHARGE YOU A PRORATABLE EARLY CANCELLATION FEE EQUIVALENT TO THE MONTHLY SUBSCRIPTION FEE TIMES THE NUMBER OF MONTHS REMAINING IN THE 24-MONTH COMMITMENT PERIOD. LIMIT ONE DISCOUNTED RATE OFFER PER ACCOUNT. -

Archaeology, History and Memory at Fort St Anne, Isle La Motte, Vermont

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2006 Enshrining the Past: Archaeology, History and Memory at Fort St Anne, Isle La Motte, Vermont Jessica Rose Desany College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Desany, Jessica Rose, "Enshrining the Past: Archaeology, History and Memory at Fort St Anne, Isle La Motte, Vermont" (2006). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626510. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-5rdk-4r65 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENSHRINING THE PAST ARCHAEOLOGY, HISTORY AND MEMORY AT FORT ST. ANNE, ISLE LA MOTTE, VERMONT A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Jessica Rose Desany 2006 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Jessica Rose Desany Approved by the Committee, May 2006 -fcmmeiLr 8<(iqd — Dr. Kathleen Bragdon, Chair Dr. Martin Gallivan For my Parents, Without whose love and support I could never have accomplished this And to Dr. Marjory Power. -

Great River Road Tennessee

Great River Road Tennessee Corridor Management Plan Corridor Management Plan Recognitions Mayor AC Wharton Shelby County Byway Consultant Mayor Jeff Huffman Tipton County David L. Dahlquist Mayor Rod Schuh Lauderdale County Governor Phil Bredesen President Mayor Richard Hill Dyer County State of Tennessee David L. Dahlquist Associates, L.L.C. Mayor Macie Roberson Lake County State Capitol 5204 Shriver Avenue Mayor Benny McGuire Obion County Nashville, TN 37243 Des Moines, IA 50312 Commissioner Susan Whitaker Pickering Firm, Inc Department of Tourist Development Byway Planning Team Architecture – Engineering – Planning – Surveying Wm. Snodgrass/Tennessee Tower 312 8th Avenue North, 25th Floor Bob Pitts, PE Nashville, TN 37243 Mississippi River Corridor – Tennessee, Inc. Principal Owner Board of Directors Director, Civil Engineering Services Ms. Marty Marbry 6775 Lenox Center Court – Suite 300 West Tennessee – Tourist Development Memphis, TN 38115 Regional Marketing & Public Relations John Sheahan Chairman/CEO John Threadgill Secretary Historical Consultant Commissioner Gerald Nicely Dr. Carroll Van West Tennessee Department of Transportation Jim Bondurant Chair – Obion - Task Force Committe Director 505 Deaderick St. Rosemary Bridges Chair – Tipton - Task Force Committee Center for Historic Preservation James K. Polk Bldg. – 7th Floor Peter Brown Chair – Dyer - Task Force Committee Middle Tennessee State University Nashville, TN 37243 Laura Holder Tennessee Civil War National Heritage Area P.O. Box 80 – MTSU Pamela Marshall Public Affairs