SURVIVALS of TEE 3HGLISH and SCOTTISH POPULAR BALLADS Lu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Issues in Ballads and Songs, Edited by Matilda Burden

SOCIAL ISSUES IN BALLADS AND SONGS Edited by MATILDA BURDEN Kommission für Volksdichtung Special Publications SOCIAL ISSUES IN BALLADS AND SONGS Social Issues in Ballads and Songs Edited by MATILDA BURDEN STELLENBOSCH KOMMISSION FÜR VOLKSDICHTUNG 2020 Kommission für Volksdichtung Special Publications Copyright © Matilda Burden and contributors, 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. Peer-review statement All papers have been subject to double-blind review by two referees. Editorial Board for this volume Ingrid Åkesson (Sweden) David Atkinson (England) Cozette Griffin-Kremer (France) Éva Guillorel (France) Sabina Ispas (Romania) Christine James (Wales) Thomas A. McKean (Scotland) Gerald Porter (Finland) Andy Rouse (Hungary) Evelyn Birge Vitz (USA) Online citations accessed and verified 25 September 2020. Contents xxx Introduction 1 Matilda Burden Beaten or Burned at the Stake: Structural, Gendered, and 4 Honour-Related Violence in Ballads Ingrid Åkesson The Social Dilemmas of ‘Daantjie Okso’: Texture, Text, and 21 Context Matilda Burden ‘Tlačanova voliča’ (‘The Peasant’s Oxen’): A Social and 34 Speciesist Ballad Marjetka Golež Kaučič From Textual to Cultural Meaning: ‘Tjanne’/‘Barbel’ in 51 Contextual Perspective Isabelle Peere Sin, Slaughter, and Sexuality: Clamour against Women Child- 87 Murderers by Irish Singers of ‘The Cruel Mother’ Gerald Porter Separation and Loss: An Attachment Theory Approach to 100 Emotions in Three Traditional French Chansons Evelyn Birge Vitz ‘Nobody loves me but my mother, and she could be jivin’ too’: 116 The Blues-Like Sentiment of Hip Hop Ballads Salim Washington Introduction Matilda Burden As the 43rd International Ballad Conference of the Kommission für Volksdichtung was the very first one ever to be held in the Southern Hemisphere, an opportunity arose to play with the letter ‘S’ in the conference theme. -

Ancient Ballads and Songs of the North of Scotland, Hitherto

1 ifl ANCIENT OF THE NOETH OF SCOTLAND, HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED. explanatory notes, By peter BUCHAN, COKRESFONDING ME3IBER OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND. " The ancient spirit is not dead,— " Old times, wc trust, are living here.' VOL. ir. EDINBURGH: PRINTED 1011 W. & D. LAING, ANI> J, STEVENSON ; A. BllOWN & CO. ABERDEEN ; J. WYLIE, AND ROBERTSON AND ATKINSON, GLASGOW; D. MORISON & CO. PERTH ; AND J. DARLING, LONDON. MDCCCXXVIII. j^^nterct! in -Stationers i^all*] TK CONTENTS V.'Z OF THK SECOND VOLUME. Ballads. N'olcs. The Birth of Robin Hood Page 1 305 /King Malcolm and Sir Colvin 6 30G Young Allan - - - - 11 ib. Sir Niel and Mac Van 16 307 Lord John's Murder 20 ib. The Duke of Athole's Nurse 23 ib. The Laird of Southland's Courtship 27 308 Burd Helen ... 30 ib. Lord Livingston ... 39 ib. Fause Sir John and IMay Colvin 45 309 Willie's Lyke Wake 61 310 JSTathaniel Gordon - - 54 ib. Lord Lundy ... 57 312 Jock and Tarn Gordon 61 ib. The Bonny Lass o' Englessie's Dance 63 313 Geordie Downie . - 65 314 Lord Aboyne . 66 ib. Young Hastings ... 67 315 Reedisdale and Wise William 70 ib. Young Bearwell ... 75 316 Kemp Owyne . 78 ib. Earl Richard, the Queen's Brother 81 318 Earl Lithgow .... 91 ib. Bonny Lizie Lindsay ... 102 ib. The Baron turned Ploughman 109 319 Donald M'Queen's Flight wi' Lizie Menzie 117 ib. The Millar's Son - - - - 120 320 The Last Guid-night ... 127 ib. The Bonny Bows o' London 128 ib. The Abashed Knight 131 321 Lord Salton and Auchanachie 133 ib. -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

The Ballad/Alan Bold Methuen & Co

In the same series Tragedy Clifford Leech Romanticism Lilian R Furst Aestheticism R. V. Johnson The Conceit K. K Ruthven The Ballad/Alan Bold The Absurd Arnold P. Hinchliffe Fancy and Imagination R. L. Brett Satire Arthur Pollard Metre, Rhyme and Free Verse G. S. Fraser Realism Damian Grant The Romance Gillian Beer Drama and the Dramatic S W. Dawson Plot Elizabeth Dipple Irony D. C Muecke Allegory John MacQueen Pastoral P. V. Marinelli Symbolism Charles Chadwick The Epic Paul Merchant Naturalism Lilian R. Furst and Peter N. Skrine Rhetoric Peter Dixon Primitivism Michael Bell Comedy Moelwyn Merchant Burlesque John D- Jump Dada and Surrealism C. W. E. Bigsby The Grotesque Philip Thomson Metaphor Terence Hawkes The Sonnet John Fuller Classicism Dominique Secretan Melodrama James Smith Expressionism R. S. Furness The Ode John D. Jump Myth R K. Ruthven Modernism Peter Faulkner The Picaresque Harry Sieber Biography Alan Shelston Dramatic Monologue Alan Sinfield Modern Verse Drama Arnold P- Hinchliffe The Short Story Ian Reid The Stanza Ernst Haublein Farce Jessica Milner Davis Comedy of Manners David L. Hirst Methuen & Co Ltd 19-+9 xaverslty. Librasü Style of the ballads 21 is the result not of a literary progression of innovators and their acolytes but of the evolution of a form that could be men- 2 tally absorbed by practitioners of an oral idiom made for the memory. To survive, the ballad had to have a repertoire of mnemonic devices. Ballad singers knew not one but a whole Style of the ballads host of ballads (Mrs Brown of Falkland knew thirty-three separate ballads). -

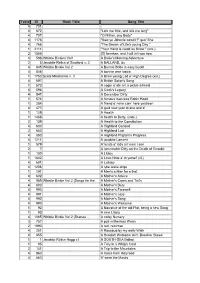

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4 701 - 4 672 "Lo'e me little, and lo'e me lang" 4 707 "O Mither, ony Body" 4 1176 "Saw ye Johnnie comin'?" quo' She 4 766 "The Dream of Life's young Day " 1 2111 "Your Hand is cauld as Snaw " (xxx.) 2 1555 [O] hearken, and I will tell you how 4 596 Whistle Binkies Vol1 A Bailie's Morning Adventure 2 5 Jacobite Relics of Scotland v. 2 A BALLAND, &c 4 845 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 A Bonnie Bride is easy buskit 4 846 A bonnie wee lassie 1 1753 Scots Minstrelsie v. 3 A Braw young Lad o' High Degree (xxi.) 4 597 A British Sailor's Song 1 573 A cogie o' ale an' a pickle aitmeal 4 598 A Cook's Legacy 4 847 A December Dirty 1 574 A famous man was Robin Hood 1 284 A friend o' mine cam' here yestreen 4 477 A guid new year to ane and a' 1 129 A Health 1 1468 A health to Betty, (note,) 2 139 A Health to the Constitution 4 600 A Highland Garland 2 653 A Highland Lad 4 850 A Highland Pilgram's Progress 4 1211 A jacobite Lament 1 579 A' kinds o' lads an' men I see 2 7 A lamentable Ditty on the Death of Geordie 1 130 A Litany 1 1842 A Love-Note a' to yersel' (xi.) 4 601 A Lullaby 4 1206 A lyke wake dirge 1 291 A Man's a Man for a that 4 602 A Mother's Advice 4 989 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Songs for the A Mother's Cares and Toil's 4 603 Nursery) A Mother's Duty 4 990 A Mother's Farewell 4 991 A Mother's Joys 4 992 A Mother's Song 4 993 A Mother's Welcome 1 92 A Narrative of the old Plot; being a new Song 1 93 A new Litany 4 1065 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Scenes … A noisy Nursery 3 757 Nursery) A puir mitherless Wean 2 1990 A red, red rose 4 251 A Rosebud by my early Walk 4 855 A Scottish Welcome to H. -

Zur Chronologie Der Englisschen Balladen

ZUR CHRONOLOGIE DER ENGLISSCHEN BALLADEN. Mit dem erscheinen ekles zehnten teiles der English and Scottish Popular Ballads lhat das grosse lebenswerk von pro- fessor Francis J. Child seeinen abschluss gefunden und kann nun die Wissenschaft der eBnglischen philologie in Amerika mit stolz die Vollendung ihresr bisherigen grössten leistung ver- zeichnen. Der zehnte teil von Child's werk bringt keine neuen balladen,* sondern als schllussteil wertvolle nachtrage, Indices, 1 Child sagte bereits im ^Advertisement to Part IX: "This ninth part completes the Collection of Enaglish and Scottish ballads to the extent of my knowledge of sources" — rmit ausnahme einer einzigen ballade ' Yowng Betrice', vgl. Kittredge 10, **TTY Der titel des Werkes scbhliesst (zum glück) unzählige 'Broadsides' aus, und selbst solche balladena wie "The Lady Isabella's Tragedy" (Percy Eel. 3, Book 2, No. 14), welchhe Child treffend nennt "perhaps absolutely the silliest ballad that was ewer made", wird man gern vermissen, aber andere nicht (wieder) abgedruckte möchte man doch gern sehen, wenngleich diese neugier bestraft werden würde, z. b. The Dainty Dowriby aus Herd's Mss (Child Einleitung zu 290; ' 9, 153); The Dragoon and Bessy (Maidment Sc. Ballads 1859 "from a Glasggow copy of 1800"; erwähnt in der einleitung zu 299; 9, 172). Warum mag wohl die .Nutbrown Maid ausgeschlossen sein? Die gründe, warum solche bänkelsäängerware wie The Tournament of Tottenham, der Mylner of Abyngton (die i masse von 'Mery Jests* und 'Mery baladesM), Whenas King Edgar did goveern this land etc. und ein ganzes heer von Elisabethanischen und spätereen broadsides ausgeschlossen wurde, kann man leicht verstehen: sie sind kunnstprodukte, wenngleich sie für das volk und den volksgeschmack geschriebben wurden (und in dieser hinsieht für die geschiente des volksgeschmacfckes von bedeutung sind). -

The Songs of Scotland Adapted to Their Appropriate Melodies

/-n^i/' /2<£ .;' JF ; 9& * Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/songsofscotlanv21849ingl THE SONGS OF SCOTLAND ADAPTED TO THEIR APPROPRIATE MELODIES ARRANGED WITH PIANOFORTE ACCOMPANIMENTS BY G. F. GRAHAM, T. M. MUDIE, J. T. SURENNE, H. E. DIBDIN, FINLAY DUN, &c. 3llu§trnteb roitf) historical, SSiograpfjical, anb Critical SftottceS BY GEOEGE FAEQUHAE GEAHAM, AUTHOR OP THE ARTICLE "MUSIO" IN THE SEVENTH EDITION OP THE ENCYCLOPEDIA BRITANNICA. ETC. ETT. VOL. II. WOOD AND CO., 12, WATERLOO PLACE, EDINBURGH; J. MUIR WOOD AND CO., 42, BUCHANAN STREET, GLASGOW ; OLIVER BOYD, EDINBURGH; & CRAMER, BEALE, & CHAPPELL, REGENT STREET; CHAPPELL, NEW BOND STREET; ADDISON & HODSON, REGENT STREET; J. ALFRED NOVELLO, DEAN STREET; AND SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, & CO., LONDON. MDCCCXLIX. EDINHURGIi: HUNTED BY T. CONSTABLE, PHIHTBH TO TOE MAJESTY. 1 INDEX TO THE FIRST LINES OF THE SONGS IN THE SECOND VOLUME FA08 PAr.a Adieu, Dundee ! from Mary parted, . 02 O lay thy loof in mine, lass, 116 And are ye sure the news is true \ {-A pp. 159,) 64 O, lassie, art thou sleepin' yet ? 22 And O, for ane-and-twenty, Tam ! {A pp. 167,) 144 O, Mary, at thy window be, 8 And ye shall walk in silk attire, (App. 158,) . 18 O my love is like a red red ruse, (App. 158,) . 28 Argyle is my name, and you may think it strange, 1 14 Oh ! thou art all so tender, 34 At AA'ilHe's wedding on the green, (App. 163,) 1 18 O, wae's my heart ! O, wae's my heart ! (App. -

Robert Burns, by Auguste Angellier 1

Robert Burns, by Auguste Angellier 1 Robert Burns, by Auguste Angellier The Project Gutenberg EBook of Robert Burns, by Auguste Angellier This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Robert Burns Vol. II., Les Oeuvres Author: Auguste Angellier Release Date: December 8, 2008 [EBook #27451] Language: French Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ROBERT BURNS *** Produced by Robert Connal, Christine P. Travers and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF/Gallica) at http://gallica.bnf.fr) [Note au lecteur de ce fichier digital: Seules les erreurs clairement introduites par le typographe ont été corrigées.] AUGUSTE ANGELLIER DOCTEUR ÈS LETTRES, PROFESSEUR À L'UNIVERSITÉ DE LILLE. Robert Burns, by Auguste Angellier 2 ROBERT BURNS II LES OEUVRES PARIS, HACHETTE & Cie. 1893. INTRODUCTION. On s'étonnera peut-être de ne trouver, dans les pages qui suivent, aucun aperçu sur la formation du génie de Burns, aucun essai pour montrer de quels éléments il se compose, quelle part en revient à la race, au climat, aux habitudes de vie. C'est de parti-pris que nous nous sommes interdit toute tentative de ce genre. Nous concevons une étude aussi précise et aussi poussée qu'il est possible de la faire des caractères, des limites, de la force d'un génie, ou, pour mieux dire, de ses manifestations extérieures. -

Incest in Ballads: the Availability of Cultural Meaning EBEOGU, AFAM N

Lore and Language The Journal of the Centre for English Cultural Tradition and Language Editor J.D.A. Widdowson Centre for English Cultural Tradition and Language, University of Sheffield Editorial Board N .F . Blake, University of Sheffield D.O. Buchan, Memorial University of Newfoundland G . Cox, University of Reading D .G. Hey, University of Sheffield J.M. Kirk, The Queen ·s University of Belfast R . L e ith, Leamington Spa C. Neilands, The Queen's University of Belfast P .S. Smith, Memorial University of Newfoundland © 1993 Hisarlik Press. Apart fro1n any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticis1n or review, as pennitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, or where reproduction is required for classroon1 use or coursework by students, this publication 1nay only be reproduced, stored or trans1nitted, in any fonn or by any tneans, with the prior pennission in writing of the publishers. US copyright law applicable to users in the USA. Lore and Language is published twice annually, in January and July. Volutne 11 is a single vol mne ( cotnprising two issues) covering two years, 1992-1993; Volutne 12 will cover 1994. Subscription rates for Volutne 11 are: Institutional, £50.00; Personal, £12 (all prices in Sterling). Send pay1nent to Hisarlik Press, 4 Catisfield Road, Enfield Lock, Middlesex EN3 6BD, UK, or credit card details to Vine House Distribution, Waldenbury, North Cointnon, Chailey, East Sussex BNg 4DR, UK. All other business correspondence concerning Volutne 11 and later volutnes should be addressed to Hisarlik Press, 4 Catisfield Road, Enfield Lock, Middlesex EN3 6BD, UK; tel. -

Round People: Bob Dylan and the Street Ballad

Come gather ‘round people Bob Dylan and the Street Ballad Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von David SAMITSCH Am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: Ao. Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. phil. Hugo Keiper Graz, 2018 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen nicht benützt und die den benutzten Quellen wört- lich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Ich habe diese Dip- lomarbeit bisher weder im In- noch im Ausland in irgendeiner Form als Prüfungsarbeit vorge- legt. Graz, Mai 2018 ………….………………….. David Samitsch “The times, they are a-changin’” – nach sechs Jahren des Studiums steht nun eine Zeitenwende in meinem Leben bevor. Es ist an der Zeit, inne zu halten und mich bei den Menschen zu bedan- ken, die mich auf diesem Stück des Weges unterstützt haben. Besonderer Dank gilt meiner Familie, die mich in allen erdenklichen Formen unterstützt hat und ohne die dies papierne Zeugnis meiner erfolgreichen Laufbahn wohl nie zustande gekom- men wäre. Ein herzliches Danke dafür! Des Weiteren möchte ich mich auch bei meinem Betreuer Ao. Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. phil. Hugo Keiper für seine gewissenhafte Betreuung, zahlreiche früchtebringende Anreize, sein Vertrauen und seine außerordentliche Unterstützung bedanken. “How many times can a comma be put In a space where it’s counter-intuitive? The answer, my friend, is luckily not in print The answer is luckily not in print!” Last but not least, ein herzliches Dankeschön an Mag.Veronika Zeppetzauer für das großartige Lektorat meiner Arbeit auch bzw. -

Of Child Ballads

Alphabetical index to the Child Ballads While working on folk songs in manuscript I wanted to have in front of me a list of the Child ballads with their numbers. Child himself does not supply such a list and the index of my edition of Kittredge* was too small to scan. Steve Roud kindly scanned his for me. I then found that what I really wanted was an alphabetical list - so here it is: Adam Bell, Clim Of The Clough And William Of Cloudesly Child 116 Alison And Willie Child 256 Allison Gross Child 35 Andrew Lammie Child 233 Archie o Cawfield Child 188 Auld Matrons Child 249 Babylon (or The Bonnie Banks of Fordie) Child 14 Baffled Knight, The Child 112 Bailiff's Daughter Of Islington , The Child 105 Baron o Leys, The Child 241 Baron Of Brackley, The Child 203 Battle Of Harlaw, The Child 163 Battle Of Otterburn, The Child 161 Battle Of Philiphaugh, The Child 202 Beggar-Laddie, The Child 280 Bent Sae Brown, The Child 71 Bessy Bell And Mary Gray Child 201 Bewick And Graham Child 211 Blancheflour And Jellyflorice Child 300 Bold Pedlar And Robin Hood, The Child 132 Bonnie Annie Child 24 Bonnie House o Airlie, The Child 199 Bonnie James Campbell Child 210 Bonnie Lizie Baillie Child 227 Bonny Baby Livingston Child 222 Bonny Barbara Allan Child 84 Bonny Bee Hom Child 92 Bonny Birdy, The Child 82 Bonny Earl Of Murray, The Child 181 Bonny Hind, The Child 50 Bonny John Seton Child 198 Bonny Lass Of Anglesey, The Child 220 Bothwell Bridge Child 206 Boy And The Mantle, The Child 29 Braes o Yarrow, The Child 214 Broom Of Cowdenknows, The Child 217 Broomfield -

The Ophelia Versions: Representations of a Dramatic Type, 1600-1633

THE OPHELIA VERSIONS : REPRESENTATIONS OFA DRAMATIC TYPE, 1600-1633 Fiona Benson A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 2008 Full metadata for this item is available in the St Andrews Digital Research Repository at: https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/478 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons License The Ophelia Versions: Representations of a Dramatic Type, 1600-1633 Fiona Benson A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of St Andrews School of English August 2007 ii ABSTRACT ‘The Ophelia Versions: Representations of a Dramatic Type from 1600-1633’ interrogates early modern drama’s use of the Ophelia type, which is defined in reference to Hamlet’s Ophelia and the behavioural patterns she exhibits: abandonment, derangement and suicide. Chapter one investigates Shakespeare’s Ophelia in Hamlet, finding that Ophelia is strongly identified with the ballad corpus. I argue that the popular ballad medium that Shakespeare imports into the play via Ophelia is a subversive force that contends with and destabilizes the linear trajectory of Hamlet’s revenge tragedy narrative. The alternative space of Ophelia’s ballad narrative is, however, shut down by her suicide which, I argue, is influenced by the models of classical theatre. This ending conspires with the repressive legal and social restrictions placed upon early modern unmarried women and sets up a dangerous precedent by killing off the unassimilated abandoned woman.