Cultural Resources Inventory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inland Empire Family Resource Center Coalition (Iefrcc)

2012 INLAND EMPIRE Update June 1 Inland Empire Directory of FAMILY RESOURCE CENTERS J ~A{ /ilL I mily Re ourc C nt r FAMILY Hearts&Lives RESOURCE CENTER Resource Directory is provided by the Inland Empire Family Resource Center Coalition (ieFRCC) 2012 The Directory of Family Resource Centers in the Inland Empire is a compilation of known Family Resource Centers operating in the Inland Empire. The purpose is to improve the delivery of client services in San Bernardino County and Riverside County. The following Family Resource Centers are provided as a resource and not a referral. It is a collaborative process and every effort is made to represent each Family Resource Center with their most current services and contact information. However funding, staff transitions, and changes in client services in the Inland Empire can make it challenging for the Directory to be current at time of printing and online updates. Family Resource Centers that do not contain complete contact information & description of services have not been confirmed prior to printing of this Directory. Updates to the Directory are quarterly during the following months: January, April, July, and October. To download the most recent copy visit www.ieFRC.org Your help in keeping the Directory most current is appreciated and can help service providers that are using the Directory link clients more effectively and efficiently. To edit or add information please email [email protected] Family Resource Centers that are presented in the directory in bold and underlined are current members of the Inland Empire Family Resource Center Coalition (ieFRCC); creator and administer of the Directory. -

Resource Directory

Superior Court of California County of San Bernardino RESOURCE DIRECTORY Directory includes services for: Anger Management Co-Parenting Domestic Violence Shelters Domestic Violence/Emergency Numbers Emergency Services Children & Family Services Victim/Witness Services Individual, Couple, Family & Child Counselors Parenting Classes Substance Abuse Treatment/Services 730 Child Custody Evaluations DISCLAIMER: The programs listed have identified themselves to the San Bernardino County Superior Court as providers in the County of San Bernardino. These programs are not affiliated with the court, and each program is independently responsible for compliance with any and all applicable legal requirements. The court does not endorse, evaluate, supervise, or monitor these programs. ADVERTENCIA: Los programas mencionados han indicado al Tribunal Superior de San Bernardino que son proveedores en esta area. Estos programas no están afiliados al Tribunal y cada programa es independientemente responsable por el cumplimiento de todos los requisites legales. El Tribunal no promociona, ni evalúa, ni supervisa, ni monitorea estos programas. Revi sed 1-31-19 1 Superior Court of California County of San Bernardino FAMILY COURT SERVICES DIVISION RESOURCE DIRECTORY - TABLE OF CONTENTS Anger Management 3-7 Co-Parenting Classes 8-11 Domestic Violence Shelters 12-13 Domestic Violence / Emergency Phone Numbers 14 Emergency Services 15-17 Children & Family Services 18 Victim / Witness Services 19 Individual, Couple, Family & Child Counselors 20-25 Parenting Classes 26-32 Substance Abuse Treatment / Services 33-41 730 Child Custody Evaluations 42-43 2 Superior Court of California County of San Bernardino Anger Management DISCLAIMER: The programs listed have identified themselves to the San Bernardino County Superior Court as providers in the Co u n t y of San Bernardino. -

Bear Valley Water Sustainability Study Final

Bear Valley Water Sustainability Study • December 2016• Recycled Water Facilities Planning Study for the Bear Valley Water Sustainability Project Prepared for Big Bear Area Regional Wastewater Agency Big Bear City Community Services District Big Bear Lake Department of Water and Power Big Bear Municipal Water District Prepared Under the Responsible Charge of: Laine Carlson 12/21/2016 Bear Valley Water Sustainability Project Acknowledgements Recycled Water Facilities Planning Study 12/21/2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The project team for this Recycled Water Facilities Planning Study (Study) for the Bear Valley Water Sustainability Project would like to acknowledge the valuable input and guidance received from the Board of Directors of the Big Bear Area Regional Wastewater Agency: David Caretto, Chairman representing the City of Big Bear Lake John Green, Vice Chairman representing Big Bear Area Community Services District Elizabeth Harris, Secretary representing San Bernardino County Service Area 53B Richard Herrick, Jr., Director representing City of Big Bear Lake Paul Terry, Director representing Big Bear Area Community Services District The Study was funded in part by a Water Recycling Facilities Planning Grant from the California State Water Resources Control Board Water Recycling Funding Program. The Study for the Bear Valley Water Sustainability Project was prepared by Water Systems Consulting, Inc. The primary authors are: Laine Carlson, P.E. Joshua Reynolds, M.S., P.E. Kaylie Ashton, E.I.T. Matt Rodrigues, M.S., P.E. Emily Iskin, M.S., E.I.T. Water Systems Consulting, Inc. would like to acknowledge the significant contributions of the Project Team. Steve Schindler Fred Uhler Scott Heule, C.H.G. -

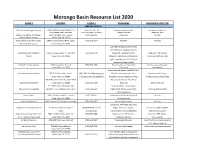

Morongo Basin Resource List 2020

Morongo Basin Resource List 2020 AGENCY ADDRESS PHONE # PROGRAMS INSURANCE ACCEPTED MENTAL HEALTH Affiliated Psychological Services 7293 Dumosa Avenue, Suite 8 - YV (760)369-7166 - YV Therapy, Psychiatric Svcs. Private ins., Medi-Cal, 6274 Adobe Road - 29 Palms (760) 367-3290 - 29 Palms Medical Support Medicare, IEHP Joshua Tree Center for Change - 61607 29 Palms Hwy., Suite D (760) 366-8641 Drug Court No Cost Mental Health Systems Joshua Tree, CA 92252 Yucca Valley Center for Change - 58945 Business Center Drive, Suite J (760) 369-1074 Recovery No Cost Mental Health Systems Yucca Valley, CA 92284 Early Identification & Intervention Svcs (EIIS), Screening Assessment Desert/Mountain Children's 58967 Business Center Dr., Ste C & D (760) 369-3130 Referral & Treatment (SART) Medi-Cal, IEHP, Private Center Yucca Valley, CA 92284 Children's Intensive Svcs (CIS) School Insurances, SAP (no cost) Aged Treatment Svcs (SATS) School Assistance Program (SAP) Family Service Association 7245 Joshua Lane, Suite A (760) 820-1430 Parenting Classes, Supervised No Cost, age and location Yucca Valley, CA 92284 Visitations requirements General Mental Health, CalWORKs MH, Hi Desert Behavioral Health 57407 29 Palms Hwy., Suite F (760) 366-1541 (DBH programs) FSP, MH Court, Psychiatric Svcs., Medicare, Dual Choice, Yucca Valley, CA 92284 (760) 366-1542 (IOP programs) Medicare intensive Outpatient Prog. Private insurance, Medi-Medi 58923 Business Center Dr., Suite D & E Wraparound, Success First/Early Lutheran Social Service Yucca Valley, CA 92284 (760) 365-7209 Wrap TBS Medi-Cal & IEHP YV - 56970 Yucca Trail, Suite 304 Domestic Violence Class, Anger New Horizons Counseling 29 Palms - 6455 Mesquite Ave., Ste. -

Homeless Resource Guide

Board of Supervisors Robert Lovingood Janice Rutherford James Ramos Curt Hagman Josie Gonzales First District Second District Third District Fourth District Fifth District Supervisor Supervisor Supervisor Supervisor Supervisor BEHAVIORAL HEALTH SHERIFF-CORONER DIRECTOR John McMahon 2 CaSonya Thomas Homeless Outreach Support Team (HOST) The mission of H.O.P.E. is to balance proactive outreach with enforcement of the law, while connecting members of the homeless population with resources that may help them transition from homelessness. The ultimate goal is to reduce the rate of recidivism, incarceration, and reduce the current costs associated to homeless related crime. For more information or assistance contact H.O.P.E. at: Phone: 909-387-0623 Toll Free 1-844-811-HOPE (4673) Or by email: [email protected] http://cms.sbcounty.gov/sheriff/GeneralInfo/HOPE.aspx Homeless Outreach Proactive Team (HOPE) HOST is an outreach based program providing services in the field to engage those chronically homeless individuals with mental illness into permanent supportive housing. HOST collaborates with the Sheriff’s Homeless Outreach Proactive Enforcement (HOPE) team to conduct outreach events, go out into the field, and engage the most difficult and hard to reach clients. HOST staff works with qualified individuals to complete the necessary applications and assessments in the field and, upon receipt of housing voucher, will assist the individual to locate and move into housing. HOST continues to offer recovery-based wrap around case management services to the individual to assist them to recover, gain wellness, and reintegrate into the community with the ultimate goal of independence and self-sufficiency. -

Clinic Names

List of grant recipients Agency City County Southern CA Jenesse Center, Inc. Los Angeles Los Angeles Center for the Pacific-Asian Family Los Angeles Los Angeles Southern CA Alcohol & Drug Program (Angel Step Downey Los Angeles Inn) 1736 Family Crisis Center Redondo Beach Los Angeles Sojourn Services Santa Monica Los Angeles Women's & Children's Crisis Center Whittier Los Angeles Su Casa Family Crisis & Support Center Artesia Los Angeles Rainbow Services, Ltd. San Pedro Los Angeles Peace & Joy Care Center Carson Los Angeles WomenShelter of Long Beach Long Beach Los Angeles Haven House Pasadena Los Angeles YWCA of Glendale, Domestic Violence Project Glendale Los Angeles Haven Hills Canoga Park Los Angeles Domestic Violence Center of the Santa Clarita Valley Nehall Los Angeles Family Violence Project of Jewish Family Services Sherman Oaks Los Angeles House of Ruth Claremont Los Angeles YWCA Wings West Covina Los Angeles South Bay Community Services Chula Vista San Diego Valley Oasis Shelter (Antelope Valley DV Council) Lancaster Los Angeles Community Resource Center Encinitas San Diego Women's Resource Center Oceanside San Diego YWCA of San Diego County San Diego San Diego Center for Community Solutions San Diego San Diego Interval House Seal Beach Orange Human Options, Inc Irvine Orange Laura's House San Clemente Orange Women's Transitional Living Center (WTLC) Orange Orange Interface Children Family Services Camarillo Ventura Coalition to End Domestic & Sexual Violence Oxnard Ventura Totals (29) Inland Empire Center for Family Solutions/Women Haven El Centro Imperial Shelter From the Storm, Inc. Palm Desert Riverside Alternatives to Domestic Violence Riverside Riverside Morongo Basin Unity Home Joshua Tree San Bernardino Desert Sanctuary, Inc. -

Morongobasinatp FINA

City of Indio FEBRUARY 2019 The following Morongo Basin Active Transportation Plan was funded by the Southern California Association of Governments’ (SCAG) Sustainable Planning Grant Program. Acknowledgments Project Management Team (PMT) Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) County of San Bernardino City of Twentynine Palms Town of Yucca Valley Consultant Team: KOA Corporation Leslie Scott Consulting (LSC) Elwood & Associates Arts Connection of San Bernardino ii MORONGO BASIN ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 3 CHAPTER 4: TOOLBOXES 81 1.1. About Morongo Basin 4 4.1. Engineering Tools 83 1.2. Morongo Basin Communities 6 4.2. School Zone Signage & Markings Guide 93 1.3. Placemaking & Public Art in the Morongo Basin* 12 4.3. SRTS Programming Tools 97 1.4. Goals & Objectives 14 4.4. Creative Placemaking & Programming* 103 CHAPTER 2: PLANNING PROCESS 19 CHAPTER 5: RECOMMENDATIONS 113 2.1 Project Management Team 20 5.1. Regional Active Transportation Network 114 2.2 Technical Advisory Committee 21 5.2. Regional Active Transportation Corridors 122 2.3. Community & Public Involvement 22 5.3. Local Focus Areas 124 2.4. Public Art-Related Outreach & Engagement* 34 5.4. Public Art-Related Strategies & Recommendations* 128 CHAPTER 3: EXISTING CONDITIONS 41 CHAPTER 6: IMPLEMENTATION PLAN 130 3.1. Existing Plans & Policies* 42 6.1. Cost Summary 132 3.2. Land Use 48 6.2. Project Prioritization 134 3.3. Activity Centers & Destinations 52 6.3. Funding Opportunities* 143 3.4. Transit Connectivity 54 6.4. Project Phasing 151 3.5. Health & Environment 57 6.5. Performance Measures 152 3.6. -

San Bernardino Associated Governments

San Bernardino County Maglev to Las Vegas Los Angeles County San Bernardino County KENDALL RIVERSIDE Long Range Transit Plan 40TH RANCHO CUCAMONGA 15 215 Final ReportSIERRA TC STATE 20TH HIGHLAND 210 210 19TH DEL ROSA EUCLID ETIWANDA FONTANA E AYALA MILLIKEN HIGHLAND BASELINE PALM CARNELIAN BASELINE WATERMAN STERLING BOULDER UPLAND ARCHIBALD 9TH MEDICAL CENT ER CITRUS GREENSPOT CHURCH HAVEN SIERRA RIALTO 5TH 3RD Metro Gold FOOTHILL 2ND Line to RIALTO TC ARROW Pasadena G CHERRY 210 ARROWHEAD SAN BERNARDINO JERSEY ALDER MT MT VERNON MILL 2 SIERRA TC 2 TC MERRILL 2 RANCHO 6TH ORANGE VINEYARD MONTEVISTA STATE 38 4TH SAN BERNARDINO TIPPECANOE MOUNTAIN 10 MILL CREEK To Pomona RIVERSIDE CLEVELAND TC LUGONIA MONTCLAIR INLAND EMPIRE ONTARIO MILLS VALLEY G ALABAMA Transcenter PEPPER HOSPITALITY REDLAND S HOLT SP AIRPORT CALIFORNIA TC TC LA CADENA STATE ANDERSON CITRUS SANTA ANA TC 9TH CRAFTON CACTUS CAJON WABASH SAND CANYON MISSION 15 BARTON JURUPA LOCUST ONTARIO CEDAR COLTON WASHINGTON TC YUCAIPA BRYANT FRANCIS MT VERNON LOMA LINDA 2 MILLIKEN CYPRESS YUCAIPA CENTRAL PHILADELPHIA 2 MU LBERRY 10 60 215 AVENUE E WALNUT REDLANDS HAVEN GROVE GRAND TERRACE RAMONA RIVERSIDE ARCHIBALD CHINO TC Riverside County GRAND Replace RTA EDISON SANANTONIO Route 36 PEYTON CHINO HILLS CHINO In Association with KIMBALL GROVE Hexagon Transportation Consultants, Inc. To Cal Poly To LimonitePatti Post & Associates Pomona Shopping Center Vision BRT Routes San Bernardino Avenue Vision Maglev TC Transit Center CHINO HILLS M.I.G. E Street Grand/Edison Avenues Vision Rail -

City of Big Bear Lake CITY COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA JANUARY 11

City of Big Bear Lake City of Big Bear Lake CITY COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA JANUARY 11, 2010 COUNCILMEMBERS Mayor Elizabeth Harris Mayor Pro Tern Bill Jahn Councilmember Rick Herrick Councilmember Michael Karp Councilmember Darrell Mulvihill CITY STAFF City Manager Jeff Mathieu City Attorney Steve Deitsch Chief Operations Officer Kathleen Smith City Clerk Katherine Jefferies ORDER OF BUSINESS Open Session 6:30 p.m. 39707 BIG BEAR BOULEVARD Big Bear Lake, California City of Big Bear Lake INFORMATION FOR THE PUBLIC The City Council meets regularly on the second and fourth Monday of the month at 6:30 p.m. in the Council Chambers located at 39707 Big Bear Blvd. Members of the City Council also sit as the Fire Protection District Board and the Improvement Agency PROCEDURE TO ADDRESS THE CITY COUNCIL, FIRE BOARD OR IMPROVEMENT AGENCY The Council, Fire Board and improvement Agency encourage free expression of all points of view. To allow all persons to speak, given the length of the Agenda, please keep your remarks brief. If others have already expressed your position, you may simply indicate that you agree with a previous speaker. If appropriate, a spokesperson may present the views of your entire group. To encourage all views and promote courtesy to others, the audience should refrain from clapping, booing or shouts of approval or disagreement. PUBLIC COMMUNICATIONS The public may address the Council, Fire Board or Agency by completing a speaker card and submitting it to the City Clerk. The speaker cards are located on the table in the back of the 'Chambers. During "Public Communications," your name will be called. -

$7,935,000 Morongo Unified School District 2012 General Obligation Refunding Bonds Final Opinion ______

NEW ISSUE -- FULL BOOK-ENTRY RATING: Moody’s: “Aa3” See “RATING” herein In the opinion of Bowie, Arneson, Wiles & Giannone, Newport Beach, California, Bond Counsel, subject, however, to certain qualifications described herein, under existing laws, rulings and court decisions, and assuming, among other matters, the accuracy of certain representations and compliance with certain covenants, interest on the Refunding Bonds is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes under Section 103 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (“Code”). In the further opinion of Bond Counsel, interest on the Refunding Bonds is not an item of tax preference for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax imposed on individuals and corporations; however, Bond Counsel observes that such interest is included as an adjustment in the calculation of federal corporate alternative minimum taxable income and may therefore affect a corporation’s alternative minimum tax liabilities. In the further opinion of Bond Counsel, interest on the Refunding Bonds is exempt from State of California personal income taxation. Bond Counsel expresses no opinion regarding or concerning any other tax consequences related to the ownership or disposition of, or the accrual or receipt of interest on, the Refunding Bonds. See “TAX MATTERS.” $7,935,000 MORONGO UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT (San Bernardino County, California) 2012 General Obligation Refunding Bonds Dated: Date of Delivery Due: August 1, as shown on inside front cover Issuance. The Morongo Unified School -

Hdwd Wastewater Pipeline Project (Phases Ii and Iii)

IDENTIFICATION AND EVALUATION OF HISTORIC PROPERTIES HDWD WASTEWATER PIPELINE PROJECT (PHASES II AND III) In and near the Town of Yucca Valley San Bernardino County, California For Submittal to: Hi-Desert Water District 55439 29 Palms Highway Yucca Valley, California 92284 and State Water Resources Control Board 1001 I Street/P.O. Box 944212 Sacramento, CA 94244 Prepared for: Jericho Systems, Inc. 47 N 1st Street Redlands, CA 92373 Prepared by: CRM TECH 1016 E. Cooley Drive, Suite A/B Colton, CA 92324 Bai “Tom” Tang, Principal Investigator Michael Hogan, Principal Investigator August 5, 2019 CRM TECH Contract No. 3446 Title: Identification and Evaluation of Historic Properties: HDWD Wastewater Pipeline Project (Phases II and III), in and near Town of Yucca Valley, San Bernardino County, California Author(s): Bai “Tom” Tang, Principal Investigator/Historian Deirdre Encarnación, Archaeologist/Report Writer Daniel Ballester, Archaeologist/Field Director Nina Gallardo, Archaeologist/Native American Liaison Consulting Firm: CRM TECH 1016 E. Cooley Drive, Suite A/B Colton, CA 92324 (909) 824-6400 Date: August 5, 2018 For Submittal to: Hi-Desert Water District 55439 29 Palms Highway Yucca Valley, California 92284 (760) 365-8333 and State Water Resources Control Board 1001 I Street/P.O. Box 944212 Sacramento, CA 94244 (916) 341-5057 Prepared for: Julie Gilbert, Environmental Project Manager Jericho Systems, Inc. 47 N 1st Street Redlands, CA 92373 (919) 307-5633 USGS Quadrangle: Joshua Tree North, Joshua Tree South, Yucca Valley North, and Yucca -

Joshua Tree Community Plan

Joshua Tree Community Plan Adopted March 13, 2007 Effective April 12, 2007 Acknowledgements The following persons contributed to the preparation of the Joshua Tree Community Plan Board of Supervisors Brad Mitzelfelt, First District Paul Biane, Second District, Chairman Dennis Hansberger, Third District Gary Ovitt, Fourth District, Vice Chairman Josie Gonzales, Fifth District Planning Commissioners Ken Anderson, First District Michael Cramer, Second District Bill Collazo, Third District Mark Dowling, Vice Chairman, Fourth District Audrey Mathews, Chair, Fifth District General Plan Advisory Committee Mark Bulot, Redlands Ted Dutton, Lake Arrowhead Scott Frier, Helendale Matt Jordan, Redlands Michael Kreeger, Chino Hills Jornal K. Miller, Muscoy Ken Morrison, Yucca Valley Kathy Murphy, Fawnskin Mark Nuaimi, Fontana Marvin Shaw, Lake Arrowhead Doug Shumway, Apple Valley Jean Stanton, Bloomington Eric Swanson, Hesperia Joshua Tree Community Plan Committee Mindy Kaufman Iona Chelette Celeste Doyle Julian Gonzalez Nancy Karl 2 April 12, 2007 Additional Contributors Joshua Tree Municipal Advisory Committee Joshua Tree Chamber of Commerce Local Homeowners Associations Joshua Tree Community Advocates Joshua Tree National Park and Joshua Tree National Park Association Joshua Basin Water District Morongo Basin Transportation Authority The Citizens of Joshua Tree County Staff Julie Rynerson Rock, AICP, Director, Land Use Services Department Randy Scott, AICP, Deputy Director, Advance Planning Jim Squire, AICP, Supervising Planner Carrie Hyke, AICP,