Hooded Crane (Grus Monachus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goldman Et Al. (2016) Monitoring of the Ecological Security in the North-Western Region of the Republic …

ISSN 2056-9386 Volume 3 (2016) issue 3, article 2 Monitoring of the ecological security in the north- western region of the Republic of Sakha, Russian Federation 俄罗斯联邦萨哈共和国西北地区的生态安全监测 Albina A. Goldman, Elena V. Sleptsova, Raissa P. Ivanova Mirny Polytechnic Institute (branch) of Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University (NEFU), Mirny, Tikhonova street 5, build.1, Russian Federation [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Accepted for publication on 3rd September 2016 Abstract – The paper is devoted to the environmental diamonds and hydrocarbon crude are located in western and impact of industrial sector in Western Yakutia and the south-western parts of the republic. The largest diamond, oil role of the Mirny Polytechnic Institute (branch) of the and gas fields are situated in Western Yakutia. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University in training specialists for oil and gas and diamond mining industries II. INDUSTRIAL SECTORS OF THE REGION and the research carried out at the educational and scientific laboratory of complex analysis of The area of disturbed lands in Mirny district ranks second anthropogenic disturbances of the Institute on in the Republic after the Neryungrinsky district (about 9 compliance with the requirements. thousand hectares). Key words – environment, industry, oil and gas, diamond The history of diamond mining in Yakutia dates back to mining, ecological monitoring, East Siberia. 1954, when prospectors discovered the first diamond pipe, Zarnitsa (‘Summer Lightning’). In 1957 the Soviet I. INTRODUCTION government established Yakutalmaz Group of enterprises, and diamond mining operations commenced. Two years later The Mirny Polytechnic Institute (branch) of the the USSR sold the first parcel of Yakutian diamonds on the Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University is located in the world market. -

Climate Change and Human Mobility in Indigenous Communities of the Russian North

Climate Change and Human Mobility in Indigenous Communities of the Russian North January 30, 2013 Susan A. Crate George Mason University Cover image: Winifried K. Dallmann, Norwegian Polar Institute. http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/about/maps. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ ii 1. Introduction and Purpose ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Focus of paper and author’s approach................................................................................... 2 1.2 Human mobility in the Russian North: Physical and Cultural Forces .................................. 3 1.2.1 Mobility as the Historical Rule in the Circumpolar North ............................................. 3 1.2.2. Changing the Rules: Mobility and Migration in the Russian and Soviet North ............ 4 1.2.3 Peoples of the Russian North .......................................................................................... 7 1.2.4 The contemporary state: changes affecting livelihoods ................................................. 8 2. Overview of the physical science: actual and potential effects of climate change in the Russian North .............................................................................................................................................. -

Characterization of Gizzards and Grits of Wild Cranes Found Dead at Izumi Plain in Japan

FULL PAPER Wildlife Science Characterization of gizzards and grits of wild cranes found dead at Izumi Plain in Japan Mima UEGOMORI1), Yuko HARAGUCHI2), Takeshi OBI3) and Kozo TAKASE3)* 1)Laboratory of Veterinary Microbiology, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Agriculture, Kagoshima University, 1-21-24 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan 2)Izumi City Crane Museum, Crane Park Izumi, Izumi, Kagoshima 899-0208, Japan 3)Department of Veterinary Medicine, Joint Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kagoshima University, 1-21-24 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan ABSTRACT. We analyzed the gizzards, and grits retained in the gizzards of 41 cranes that migrated to the Izumi Plain during the winter of 2015/2016 and died there, either due to accident or disease. These included 31 Hooded Cranes (Grus monacha) and 10 White-naped Cranes (G. vipio). We determined body weight, gizzard weight, total grit weight and number per gizzard, and size, shape, and surface roundness of the grits. Average gizzard weights were 92.4 g for Hooded Cranes and 97.1 g for White-naped Cranes, and gizzard weight positively correlated with J. Vet. Med. Sci. body weight in both species. Average total grit weights per gizzard were 19.7 g in Hooded Cranes 80(4): 642–647, 2018 and 25.7 g in White-naped Cranes, and were significantly higher in the latter. Average percentages of body weight to grit weight were 0.8% in Hooded Cranes and 0.5% in White-naped Cranes. doi: 10.1292/jvms.17-0407 Average grit number per gizzard was 693.5 in Hooded Cranes and 924.2 in White-naped Cranes, and were significantly higher in the latter. -

Hooded Crane

Hooded Crane VERTEBRATA Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Panthera Category: 1 – critically endangered species at the territory of Russia The hooded crane (Grus monacha) is a small, dark crane, categorized as ‘vulnerable’ by IUCN. Distribution and Population: Distribution of Hooded Crane The estimated population of the species is approximately 9,200. The breeding grounds of this species are in south- eastern Siberia, Russian Federation, and northern China. More than 80 per cent of hooded cranes spend the winter at Izumi Feeding Station on the Japanese island of Kyushu. Small numbers are found at Yashiro in southern Japan (8,000 for wintering), in the Republic of Korea (100 for wintering) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (100 for wintering), and at several sites along the middle Yangtze River in China (1,000 for Source: BirdLife International Species Factsheet (2013): Crus breeding and wintering). Monacha Hooded cranes nest and feed in isolated sphagnum bogs scattered through the taiga in the southeastern Russian Federation, and in China, in forested wetlands in mountain valleys. Non- breeding birds are found in shallow open wetlands, natural grasslands, and agricultural fields in southern Siberia and north-eastern Mongolia. During migration, hooded cranes often associate with Eurasian and white-naped cranes. Physical features and habitats: Adult crowns are un-feathered, red, and covered with black hair-like bristles. The head and neck are snow white, which extends down the neck. The body plumage is otherwise slaty gray. The primaries, secondaries, tail, and tail coverts are black. Juvenile crown are covered with black and white feathers during the first year, and exhibit some brownish or grayish wash on their body feathers. -

Hooded Crane Nabe-Zuru (Jpn) Grus Monacha

Bird Research News Vol.4 No.1 2007.1.12. Hooded Crane Nabe-zuru (Jpn) Grus monacha Morphology and classification Life history Classification: Gruiformes Gruidae 123456789101112 wintering Total length: About 100cm Wing length: 480-530mm period migration breeding migration Tail length: 160-190mm Culmen length: 93-107mm Tarsus length: 200-230mm Breeding system: Weight: ♂ 3280-4870g ♀ 3400-3740g Hooded Cranes are monogamous. It is assumed that once they have paired, they usually maintain the pair-bond. When a partner Total length after del Hoyo (1996) and the others after Kiyosu (1978). died, however, the bereaved one sometimes mates with another bird again. Appearance: Male and female are simi- Age of the first breeding: lar in plumage coloration. Males and females are sexually mature at the age of about three They have an area of bare and five years, respectively, but unpaired females do not lay eggs, skin on the forehead. The even if they are mature (Ellis et al. 1996). skin exposed above the eye is red, but the other is Nest: black. They are charcoal There is no detailed information about the nest, but the size is as- gray all over except for sumed to vary greatly from one bird to another. There seems to be the area from the head to a nest with a diameter of several meters and a height of one meter. the nape, which is white. The study of Fujimaki et al. (1989) showed that they built a nest at They have tan bills and a height of 15-20cm above the water. The diameter of a nest was black legs. -

Passage Through Siberia a River Cruise Along the Mighty River Lena to the Arctic Aboard the MS Mikhail Svetlov 18Th August to 2Nd SEPTEMBER 2015 Scottintsy

PASSAGE THROUGH SIBERIA A river cruise along the mighty River Lena to the Arctic aboard the MS Mikhail Svetlov 18TH AUGUST TO 2ND SEPTEMBER 2015 Scottintsy he vast untouched regions of Siberia offer a unique travel experience for the genuine traveller. The scarcity of roads and railways means thatT the most common method of transportation is by river. The Lena, one of the mightiest rivers in the Russian Federation, flows through the Yakutia-Sakha Republic in north-east Siberia into the Arctic Ocean. During this unique river cruise we will sail through unspoiled natural scenery, taking a short detour to the Lena Pillars National Park before continuing downstream to where the river meets the Arctic Ocean at the polar harbour of Tiksi before heading back to Yakutsk. From the comfort of your floating hotel, the MS Mikhail Svetlov, you will see the landscape slowly change from verdant taiga to polar tundra and enjoy the magical “white nights” in a place where the sun barely sets in summer. One of the most fascinating aspects of the cruise will be the opportunity to visit the people in riverside settlements along the way. Their culture, lifestyle and language will be a constant source of wonder especially their ability to thrive in the most hostile of environments. During the cruise there will be a series of fascinating onboard lectures on the former USSR, icon painting, relations between Russia and her neighbours and Russia’s great rivers. Itinerary Highlights • “White nights” in the Arctic Circle • The legendary Lena Pillars • Unspoiled tundra and taiga scenery • The Lena River Delta and the Arctic Ocean • Ethnographical open-air museum in Sottintsy • Authentic folklore performances Yakutian Children Tundra Wildflowers www.noble-caledonia.co.uk Day 9 Tiksi. -

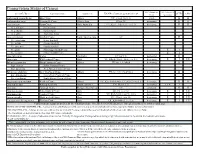

Conservation Status of Cranes

Conservation Status of Cranes IUCN Population ESA Endangered Scientific Name Common name Continent IUCN Red List Category & Criteria* CITES CMS Trend Species Act Anthropoides paradiseus Blue Crane Africa VU A2acde (ver 3.1) stable II II Anthropoides virgo Demoiselle Crane Africa, Asia LC(ver 3.1) increasing II II Grus antigone Sarus Crane Asia, Australia VU A2cde+3cde+4cde (ver 3.1) decreasing II II G. a. antigone Indian Sarus G. a. sharpii Eastern Sarus G. a. gillae Australian Sarus Grus canadensis Sandhill Crane North America, Asia LC II G. c. canadensis Lesser Sandhill G. c. tabida Greater Sandhill G. c. pratensis Florida Sandhill G. c. pulla Mississippi Sandhill Crane E I G. c. nesiotes Cuban Sandhill Crane E I Grus rubicunda Brolga Australia LC (ver 3.1) decreasing II Grus vipio White-naped Crane Asia VU A2bcde+3bcde+4bcde (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Balearica pavonina Black Crowned Crane Africa VU (ver 3.1) A4bcd decreasing II B. p. ceciliae Sudan Crowned Crane B. p. pavonina West African Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum Grey Crowned Crane Africa EN (ver. 3.1) A2acd+4acd decreasing II B. r. gibbericeps East African Crowned Crane B. r. regulorum South African Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled Crane Africa VU A2acde+3cde+4acde; C1+2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing II II Grus americana Whooping Crane North America EN, D (ver 3.1) increasing E, EX I Grus grus Eurasian Crane Europe/Asia/Africa LC unknown II II Grus japonensis Red-crowned Crane Asia EN, C1 (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Grus monacha Hooded Crane Asia VU B2ab(I,ii,iii,iv,v); C1+2a(ii) decreasing E I I,II Grus nigricollis Black-necked Crane Asia VU C2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Leucogeranus leucogeranus Siberian Crane Asia CR A3bcd+4bcd (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Conservation status of species in the wild based on: The 2015 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, www.redlist.org CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) - A taxon is Critically Endangered when it is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future. -

Co-Option in Siberia: the Case of Diamonds and the Vilyuy Sakha1,2

CO-OPTION IN SIBERIA: THE CASE OF DIAMONDS AND THE VILYUY SAKHA1,2 Susan A. Crate Institute of Environmental Sciences, Geography, and Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio 45056 Abstract: A specialist on the Vilyuy Sakha, a native non-Russian people of north- eastern Siberia, Russia, examines the public health and environmental challenges threat- ening the livelihood of the group. The paper presents a case study of political activism among the Vilyuy Sakha in the immediate post-Soviet period, as regional citizens were able to gain access to information on the pollution caused by diamond mining and other forms of industrial development. The demand for public health and environmental infor- mation, and mobilization against proposals for new mine development, emerged rapidly during the post-Soviet period, but disappeared almost as suddenly in the late 1990s. This paper explores the reasons for the disappearance of this evolving citizens’ environmental movement, arguing that a major cause was co-option by elite diamond interests. 1The following case study is based on the author’s last 12 years of work and research in the Vilyuy River regions of the western Sakha Republic, Russia. In 1991 and 1992, the author performed a contempo- rary analysis of the Sakha traditional summer festival, yhyakh, which comprised the field work for her mas- ter’s degree in folklore from UNC-Chapel Hill. In 1993, she studied the indigenous Sakha language with support from an IREX on-site language training grant. In 1994, the author received a two-year grant (1994– 1995 inclusive) from the John D. -

Detailed Species Accounts from the Threatened Birds Of

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

Testing the Utility of Mitochondrial Cytochrome Oxidase Subunit 1 Sequences for Phylogenetic Estimates of Relationships Between Crane (Grus) Species

Testing the utility of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 sequences for phylogenetic estimates of relationships between crane (Grus) species D.B. Yu*, R. Chen*, H.A. Kaleri, B.C. Jiang, H.X. Xu and W.-X. Du Department of Animal Science and Technology, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China *These authors contributed equally to this study. Corresponding author: W.-X. Du E-mail: [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 10 (4): 4048-4062 (2011) Received November 1, 2011 Accepted December 19, 2011 Published December 21, 2011 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/2011.December.21.7 ABSTRACT. Morphology and biogeography are widely used in animal taxonomy. Recent study has suggested that a DNA-based identification system, using a 648-bp portion of the mitochondrial gene cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (CO1), also known as the barcoding gene, can aid in the resolution of inferences concerning phylogenetic relationships and for identification of species. However, the effectiveness of DNA barcoding for identifying crane species is unknown. We amplified and sequenced 894-bp DNA fragments of CO1 from Grus japonensis (Japanese crane), G. grus (Eurasian crane), G. monacha (hooded crane), G. canadensis (sandhill crane), G. leucogeranus (Siberian crane), and Balearica pavonina (crowned crane), along with those of 15 species obtained from GenBank and DNA barcoding, to construct four algorithms using Tringa stagnatilis, Scolopax rusticola, and T. erythropus as outgroups. The four phylum profiles showed good resolution of the major taxonomic groups. We concluded that reconstruction of the molecular phylogenetic tree can be helpful for classification and that Genetics and Molecular Research 10 (4): 4048-4062 (2011) ©FUNPEC-RP www.funpecrp.com.br mtDNA CO1 sequences for phylogenetic estimates in Grus species 4049 CO1 sequences are suitable for studying the molecular evolution of cranes. -

The Cranes Compiled by Curt D

Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan The Cranes Compiled by Curt D. Meine and George W. Archibald IUCN/SSC Crane Specialist Group IUCN The World Conservation Union IUCN/Species Survival Commission Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Fund and The Cranes: Status Survey & Conservation Action Plan The IUCN/Species Survival Commission Conservation Communications Fund was established in 1992 to assist SSC in its efforts to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, deci- sion-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC's Action Plans, occasional papers, news magazine (Species), Membership Directory and other publi- cations are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation; to date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to Specialist Groups. As a result, the Action Plan Programme has progressed at an accelerated level and the network has grown and matured significantly. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and sup- port for species conservation worldwide. The Chicago Zoological Society (CZS) provides significant in-kind and cash support to the SSC, including grants for special projects, editorial and design services, staff secondments and related support services. The President of CZS and Director of Brookfield Zoo, George B. Rabb, serves as the volunteer Chair of the SSC. The mis- sion of CZS is to help people develop a sustainable and harmonious relationship with nature. The Zoo carries out its mis- sion by informing and inspiring 2,000,000 annual visitors, serving as a refuge for species threatened with extinction, developing scientific approaches to manage species successfully in zoos and the wild, and working with other zoos, agencies, and protected areas around the world to conserve habitats and wildlife. -

Birds of Indiana

Birds of Indiana This list of Indiana's bird species was compiled by the state's Ornithologist based on accepted taxonomic standards and other relevant data. It is periodically reviewed and updated. References used for scientific names are included at the bottom of this list. ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* Anseriformes Anatidae Dendrocygna autumnalis Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Waterfowl: Swans, Geese, and Ducks Dendrocygna bicolor Fulvous Whistling-Duck Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose Anser caerulescens Snow Goose Anser rossii Ross's Goose Branta bernicla Brant Branta leucopsis Barnacle Goose Branta hutchinsii Cackling Goose Branta canadensis Canada Goose Cygnus olor Mute Swan X Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan SE Cygnus columbianus Tundra Swan Aix sponsa Wood Duck Spatula discors Blue-winged Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cinnamon Teal Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mareca strepera Gadwall Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mareca americana American Wigeon Anas platyrhynchos Mallard Anas rubripes American Black Duck Anas fulvigula Mottled Duck Anas acuta Northern Pintail Anas crecca Green-winged Teal Aythya valisineria Canvasback Aythya americana Redhead Aythya collaris Ring-necked Duck Aythya marila Greater Scaup Aythya affinis Lesser Scaup Somateria spectabilis King Eider Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Melanitta perspicillata Surf Scoter Melanitta deglandi White-winged Scoter ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* Melanitta americana Black Scoter Clangula hyemalis Long-tailed Duck Bucephala