Senate Banking Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 Employment Report Career Management Center Visit the Career Management Center Online At

2010 Employment Report Career ManageMent Center Visit the Career Management Center online at www.gsb.columbia.edu/recruiters. Post positions online at www.gsb.columbia.edu/jobpost. reCruItIng at CoLumbia Business schooL Columbia Business School students continue to distinguish themselves with their ability to be nimble and flexible during a shifting economic and hiring landscape. employers report that Columbia MBas have the right mix of tangible business skills and social intelligence—enduring assets for any organization. the School’s focus on educating versatile business leaders who can excel in any environment is proven by a curriculum that bridges academic theory and real-world practice through initiatives like Columbia CaseWorks and the Master Class Program. the School’s cluster system and learning teams, as well as the Program on Social Intelligence, foster a team-oriented work ethic and an entrepreneurial mindset that makes creating and capturing opportunity instinctual. Students are able to add value to a wide range of organizations on day one, and the School’s extraordinary network of alumni, global business partners, and faculty members, along with its seamless integration with new York City, makes Columbia Business School stand out among its peers. the Career Management Center (CMC) works with hiring organizations across the public, private, and nonprofit sectors to develop effective and efficient recruiting strategies. recruiters can get to know the School’s talented students in a variety of ways, such as on-campus job fairs, prerecruiting functions, drop-in sessions, interviews, and educational presentations with student clubs, among other opportunities. Companies can also collaborate with the CMC to interview students closer to the time of hiring on an as-needed basis. -

Julian Robertson: a Tiger in the Land of Bulls and Bears

STRACHMAN_FM_pages 6/29/04 11:35 AM Page i Julian Robertson A Tiger in the Land of Bulls and Bears Daniel A. Strachman John Wiley & Sons, Inc. STRACHMAN_FM_pages 6/29/04 11:35 AM Page i Julian Robertson A Tiger in the Land of Bulls and Bears Daniel A. Strachman John Wiley & Sons, Inc. STRACHMAN_FM_pages 6/29/04 11:35 AM Page ii Copyright © 2004 by Daniel A. Strachman. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permis- sion of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per- copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the web at www. copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fit- ness for a particular purpose. -

Top 100 Hedge Funds

P2BW14403B-0-P01100-1--------XA P22 BARRON'S May24,2010 May24,2010 BARRON'S P11 BLACK Top 100 Hedge Funds The market’s horrors of 2008 gave way to the pleasures of 2009. John Paulson’s Paulson Credit Opportunities fund has gained a phenomenal 123% annually over the past three years. The worst-performing member of Barron’s Top 100 has returned roughly five times what the average hedge fund has risen. Currencies (USD, GBP and Euro) refer to specific currency classes of a fund. Fund 3-Year RANKING Assets Compound 2009 Total Firm 05/24/2010 2009 ’08 Name (mil) Fund Strategy Annual Return Return Company Name / Location Assets (mil) 1. nr Paulson Credit Opportunities a $4,000 Credit 122.92% 35.02% Paulson / New York $32,000 2. 2. Balestra Capital Partners 1,050 Global Macro 65.63 4.22 Balestra Capital / New York 1,225 3. nr Medallion 9,000 Quantitative Trading 62.80 38.00 Renaissance Tech / East Setauket, NY 15,000 4. 13. Element Capital 1,214 Macro/Relative Value 45.02 78.82 Element Capital / New York 1,214 IF THERE WERE EE,EU,MW,NL,SW,WE 5. nr Providence MBS Offshore 333 Mortgage-Backed Securities 44.29 85.67 Providence Investment Mgmt / Providence, RI 400 6. nr OEI Mac (USD) 355 Equity Long/Short 41.78 18.56 Odey Asset Mgmt / London 2,834 7. 1. Paulson Advantage b 4,750 Event Arbitrage 41.31 13.60 Paulson / New York 32,000 EVERATIMETOASK 8. nr SPM Structured Servicing 1,049 Mortgage-Backed Securities 39.80 134.60 Structured Portfolio Mgmt / Stamford, CT 2,725 9. -

BLUE RIDGE BANKSHARES, INC. Form S-4/A Filed 2020-12-09

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM S-4/A Registration of securities issued in business combination transactions [amend] Filing Date: 2020-12-09 SEC Accession No. 0001193125-20-313857 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER BLUE RIDGE BANKSHARES, INC. Mailing Address Business Address 17 WEST MAIN STREET 17 WEST MAIN STREET CIK:842717| IRS No.: 541470908 | State of Incorp.:VA | Fiscal Year End: 1231 LURAY VA 22835 LURAY VA 22835 Type: S-4/A | Act: 33 | File No.: 333-249438 | Film No.: 201378263 540-843-5207 SIC: 6022 State commercial banks Copyright © 2020 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Table of Contents As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on December 9, 2020 Registration No. 333-249438 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 PRE-EFFECTIVE AMENDMENT NO. 1 TO FORM S-4 REGISTRATION STATEMENT UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 BLUE RIDGE BANKSHARES, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 6021 54-1470908 (State or other jurisdiction of (Primary Standard Industrial (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or organization) Classification Code Number) Identification Number) 1807 Seminole Trail Charlottesville, Virginia 22901 Telephone: (540) 743-6521 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of registrants principal executive offices) Brian K. Plum President and Chief Executive Officer 17 West Main Street Luray, Virginia 22835 Telephone: (540) 743-6521 (Name, address, including -

BLUE RIDGE BANKSHARES, INC. Form S-4 Filed 2019-08-08

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM S-4 Registration of securities issued in business combination transactions Filing Date: 2019-08-08 SEC Accession No. 0001193125-19-216988 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER BLUE RIDGE BANKSHARES, INC. Mailing Address Business Address 17 WEST MAIN STREET 17 WEST MAIN STREET CIK:842717| IRS No.: 541470908 | State of Incorp.:VA | Fiscal Year End: 1231 LURAY VA 22835 LURAY VA 22835 Type: S-4 | Act: 33 | File No.: 333-233148 | Film No.: 191010487 540-843-5207 SIC: 6022 State commercial banks Copyright © 2019 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Table of Contents As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on August 8, 2019 Registration No. 333- UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM S-4 REGISTRATION STATEMENT UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 BLUE RIDGE BANKSHARES, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 6022 54-1470908 (State or other jurisdiction of (Primary Standard Industrial (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or organization) Classification Code Number) Identification Number) 17 West Main Street Luray, Virginia 22835 Telephone: (540) 743-6521 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of registrants principal executive offices) Brian K. Plum President and Chief Executive Officer 17 West Main Street Luray, Virginia 22835 Telephone: (540) 743-6521 (Name, address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of agent for service) Copies to: Scott H. Richter Brian L. Hager Benjamin A. McCall Lawton B. Way Williams Mullen Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP 200 South 10th Street, Suite 1600 Riverfront Plaza, East Tower Richmond, Virginia 23219 951 East Byrd Street (804) 420-6000 Richmond, Virginia 23219 (804) 788-8200 Approximate date of commencement of proposed sale of the securities to the public: As soon as practicable after this registration statement becomes effective and upon completion of the merger described herein. -

Hedge Fund Reading List "The Man Who Does Not Read Good Books Has No Advantage Over the Man Who Can't Read Them." - Mark Twain

Hedge Fund Reading List "The man who does not read good books has no advantage over the man who can't read them." - Mark Twain Behavioral Finance, Psychology Historical and Biographical Philosophy/”Ideas” Cialdini, Robert Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion Baruch, Bernard Baruch: My Own Story Bevelin, Peter Seeking Wisdom Claxton, Guy Hare Brain, Tortoise Mind Bernstein, Peter Capital Ideas, A History of Wall Street Cameron, Julia The Artist's Way Gilovich & Belsky Why Smart People Make Big Money Mistakes Brooks, John Go-Go Years: Drama & Crashing Finale Csikszentmihalyi, M. Creativity or Flow Gilovich, Thomas How We Know What Isn’t So Byrne, John Chainsaw: Notorious Career of Al Dunlap Frankl, Victor Man’s Search for Meaning Hill, Napoleon Think and Grow Rich Cunningham, L Essays of Warren Buffet Gardner, Howard The Disciplined Mind Hougen, Robert The Inefficient Stock Market Dunbar, Nicholas Inventing Money Gelb, Michael How To Think Like Leonardo DaVinci Mauboussin, M. More Than You Know Ellis & Vertin Classic II: Another Investor’s Anthology Gonzales, Laurence Everyday Survival & Deep Survival Plous, Scott The Psychology and Judgment of Decision Making Fischer, David The Great Wave Haidt, Jonathan Happiness Hypothesis Pring, Martin Investment Psychology Explained Garber, Peter Famous First Bubbles Lewis, Michael Moneyball Rosenzweig, Phil The Halo Effect Giesst, Charles Wall Street: A History Neill, Humphrey The Art of Contrary Thinking Russo, J. Decision Traps: 10 Barriers to Brilliant Decision Making Gordon, John S. The Great -

Series 2019 B Official Statement

NEW ISSUE – FULL BOOK ENTRY Ratings: Moody’s: Aaa S&P: AAA Fitch Ratings: AAA (See “RATINGS” herein) In the opinion of Bond Counsel, under current law and subject to the conditions described in “TAX MATTERS” herein, interest on the Series 2019B Bonds (a) is excludable from gross income for federal income tax purposes under Section 103 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”), and (b) is not treated as a preference item in calculating the alternative minimum tax. Bond Counsel is further of the opinion that interest on the Series 2019B Bonds is exempt from Virginia income taxation. See “TAX MATTERS” herein regarding certain other tax considerations. $150,000,000 THE RECTOR AND VISITORS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA General Revenue Pledge Bonds Series 2019B Dated: Date of Delivery Due: See Inside Cover The offered bonds identified above (the “Series 2019B Bonds”) will be issued as fully registered bonds and will be registered in the name of Cede & Co., as nominee for The Depository Trust Company (“DTC”), New York, New York, which will act as securities depository for the Series 2019B Bonds under a book-entry only system. Accordingly, Beneficial Owners of the Series 2019B Bonds will not receive physical delivery of bond certificates. See Appendix D attached hereto. The Series 2019B Bonds are payable solely from Pledged Revenues (as hereinafter defined) available to The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia (the “University”). The Series 2019B Bonds will bear interest at fixed rates and will be offered at the prices or yields set forth on the inside of this cover page. -

Hedge Fund Wisdom a Quarterly Publication by Marketfolly.Com

Q2 2014 hedge fund wisdom a quarterly publication by marketfolly.com Background: table of contents Each quarter, hedge funds are required to disclose their portfolios to the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) via 13F consensus buy/sell lists: filing. p.02 Most popular trades These filings disclose long U.S. equity positions, American hedge fund portfolios: Depositary Receipts (ADRs), stock options (puts/calls), warrants, as p.06 Baupost Group well as convertible notes. They do not disclose positions in other p.08 Berkshire Hathaway asset classes (such as commodities, currencies, or debt). They also do not reveal foreign market holdings, short sales or cash positions. p.10 Greenlight Capital p.12 Lone Pine Capital Hedge Fund Wisdom, a quarterly publication by p.15 Appaloosa Management MarketFolly.com, aggregates, updates, and analyzes the latest p.18 Pershing Square Capital portfolios of top hedge funds. This issue reveals second quarter p.20 Maverick Capital holdings as of June 30th, 2014. p.23 Third Point p.26 Blue Ridge Capital In This Issue: p.29 Paulson & Co - Consensus buy & sell lists revealing which stocks were most p.32 Tiger Management frequently traded by these managers p.35 Soros Fund p.38 Bridger Capital - Portfolio updates on 25 prominent hedge funds: data tables, p.40 Omega Advisors expert commentary & historical context on each fund’s moves p.43 Coatue Management - Equity analysis section examining 2 stocks hedge funds were p.46 Fairholme Capital buying p.49 Tiger Global p.52 Passport Capital - To navigate the newsletter, simply click on a page number in p.60 Perry Capital the Table of Contents column on the right to go to that page p.62 Glenview Capital p.65 Viking Global Quote of the Quarter: p.68 Farallon Capital p.72 Icahn Capital “Despite strong recent data on jobs and manufacturing, it remains p.74 JANA Partners unclear whether growth will be robust enough to merit tightening action by the Fed this year. -

The Road to Reform

ECONOMIC & CONSUMER CREDIT ANALYTICS ANALYSIS �� Road to Reform September 2013 The Road to Reform ebate is heating up over the future of the nation’s housing finance system. Prepared by Mark Zandi Much of the back and forth has focused on the system’s end state—whether [email protected] housing finance should be privatized, retain some form of government back- Chief Economist D stop, or even remain effectively nationalized as it is today. No matter which goal is Cristian deRitis chosen, however, reform will not succeed without an effective transition. A clearly [email protected] Senior Director - Consumer Credit articulated plan for getting from here to there is vital; otherwise policymakers will be Analytics appropriately reluctant to move down the reform path. This paper presents a clear road map to the new housing finance system.1 Contact Us Email For this paper, it is assumed that the future housing finance system will be a hybrid system. That is, pri- [email protected] vate capital will be responsible for losses related to mortgage defaults, but in times of financial crisis, when U.S./Canada private capital is insufficient to absorb those losses, the government will step in. Mortgage borrowers who +1.866.275.3266 benefit from the government backstop will pay a fee to compensate the government for potential losses. Under most proposals, between a third and half of all mortgage loans will be covered by this catastrophic EMEA (London) +44.20.7772.5454 government backstop. (Prague) While there are advantages and disadvantages to any housing finance system, a hybrid system is the +420.224.222.929 most likely to be implemented. -

Value Investor Insight Sept 30

September 29, 2016 ValuThe Leading Authority on Value Investing eInvestor INSIGHT Inside this Issue Network Effect FEATURES Some investors have a penchant for high-quality compounders and some for Investor Insight: Mark Meulenberg somewhat-hairy special situations. Mark Meulenberg has an affinity for both. Spanning the risk spectrum to find current upside in Liberty Global, INVESTOR INSIGHT aving graduated from Cornell Liberty LiLAC, Liberty SiriusXM with a degree in business, Mark and Eastman Kodak. HMeulenberg got a crash course in value investing upon joining research firm Investor Insight: Jason Karp Sanford C. Bernstein in 1996. “They fed us Seeking large “expectations gaps” in potential investments and find- breakfast, lunch and dinner at the office,” ing them today in Dish Network, he says. “We were completely immersed.” SunOpta and Leidos. Now Chief Investment Officer at VNB Wealth Management, Meulenberg has put Uncovering Value: Emerson that early education to good use. His En- Industrial-equipment suppliers are hanced Core Strategy since the beginning of boring the market to tears. Is malaise 2008 has returned 13.8% net of fees, com- unwarranted here? Mark Meulenberg pared to 7.8% for the S&P 500. Uncovering Value: Sensata VNB Wealth Management Owning both franchise businesses and Auto-supply firms can repel quality- Investment Focus: Seeks companies an eclectic mix of quirky special situations, conscious investors. This one may be with “sticky” customers and highly recurring he’s finding opportunity today in such areas worth a closer look. revenues at rare moments when short-term market sentiment turns against them. as global cable services, satellite radio and Editor’s Letter printing solutions. -

Copyrighted Material

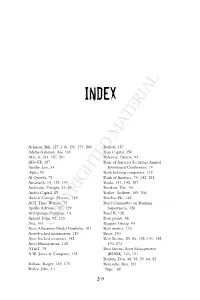

Index Ackman, Bill, 127, 146, 150, 174, 200 Bailout, 187 Adidas-Salomon AG, 101 Bain Capital, 150 AIG, 6, 181, 187, 201 Balyasny, Dmitry, 93 AIG-FP, 187 Banc of America Securities Annual Ainslie, Lee, 33 Investment Conference, 74 Alpha, 90 Bank holding companies, 142 Al Quaeda, 78 Bank of America, 74, 142, 181 Amaranth, 14, 132–133 Banks, 141, 142, 187 Anderson, Dwight, 33, 85 Barakett, Tim, 93 Andor Capital, 85 Barber, Andrew, 169, 204 Andrew Carnegie (Nasaw), 149 Barclays Plc, 142 AOL Time Warner, 75 Basel Committee on Banking Apollo Advisors, 127, 129 Supervision, 128 Archipelago Holdings, 14 Basel II, 128 Arnold, John, 92, 133 Basis points, 88 Asia, 161 Baupost Group, 93 Asset AllocationCOPYRIGHTED Model Portfolio, 194 Bear market, MATERIAL 173 Asset-backed instruments, 119 Bears, 190 Asset-backed securities, 142 Bear Stearns, 85, 86, 128, 141, 142, Asset Management, 142 170, 173 AT&T, 75 Bear Stearns Asset Management A.W. Jones & Company, 132 (BSAM), 143, 151 Benton, Dan, 48, 58, 59, 64, 85 Babson, Roger, 149, 175 Bernanke, Ben, 181 Bailey, John, 14 “Bips,” 88 209 bbindex.inddindex.indd 220909 111/17/091/17/09 99:36:04:36:04 AAMM index Black, Leon, 127 Chess King, 32 BlackRock, 145 China, 86, 95, 109 Blackstone Group, 13, 127, 144, 145, 151 Chuck E. Cheese, 204 Black Week, 182, 188 Citadel Investment Group, 11, 92, Blake, Rich, 5 102, 119 Blogging, 159–164, 180, 181, 189–190 Clarium Capital Management, 92, 190 Blue Ridge Capital, 33 Clark, Tanya, 148 Blue Wave, 1, 144, 155, 177 Client letters, 202 Blum, Michael, 26, 76, 106, 111, -

General Motors Company; Rule 14-8 No-Action Letter

March 7, 2017 Marc S. Gerber Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP [email protected] Re: General Motors Company Incoming letter dated February 28, 2017 Dear Mr. Gerber: This is in response to your letter dated February 28, 2017 concerning the shareholder proposal submitted to GM by John Chevedden. We also have received letters from the proponent dated March 3, 2017, March 5, 2017 and March 7, 2017. Copies of all of the correspondence on which this response is based will be made available on our website at http://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/cf-noaction/14a-8.shtml. For your reference, a brief discussion of the Division’s informal procedures regarding shareholder proposals is also available at the same website address. Sincerely, Matt S. McNair Senior Special Counsel Enclosure cc: John Chevedden ***FISMA & OMB Memorandum M-07-16*** March 7, 2017 Response of the Office of Chief Counsel Division of Corporation Finance Re: General Motors Company Incoming letter dated February 28, 2017 The proposal requests that the board take the steps necessary to enable at least 50 shareholders to aggregate their shares for purposes of proxy access. There appears to be some basis for your view that GM may exclude the proposal under rule 14a-8(i)(10). Based on the information you have presented, it appears that GM’s policies, practices and procedures compare favorably with the guidelines of the proposal and that GM has, therefore, substantially implemented the proposal. Accordingly, we will not recommend enforcement action to the Commission if GM omits the proposal from its proxy materials in reliance on rule 14a-8(i)(10).