Use of Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal

John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal Ágnes Juhász-Ormsby The Episcopal Library of St. John’s is among the few nineteenth- century libraries that survive in their original setting in the Atlantic provinces, and the only one in Newfoundland and Labrador.1 It was established by John Thomas Mullock (1807–69), Roman Catholic bishop of Newfoundland and later of St. John’s, who in 1859 offered his own personal collection of “over 2500 volumes as the nucleus of a Public Library.” The Episcopal Library in many ways differs from the theological libraries assembled by Mullock’s contemporaries.2 When compared, for example, to the extant collection of the Catholic bishop of Victoria, Charles John Seghers (1839–86), whose life followed a similar pattern to Mullock’s, the division in the founding collection of the Episcopal Library between the books used for “private” as opposed to “public” theological study becomes even starker. Seghers’s books showcase the customary stock of a theological library with its bulky series of manuals of canon law, collections of conciliar and papal acts and bullae, and practical, dogmatic, moral theological, and exegetical works by all the major authors of the Catholic tradition.3 In contrast to Seghers, Mullock’s library, although containing the constitutive elements of a seminary library, is a testimony to its found- er’s much broader collecting habits. Mullock’s books are not restricted to his philosophical and theological studies or to his interest in univer- sal church history. They include literary and secular historical works, biographies, travel books, and a broad range of journals in different languages that he obtained, along with other necessary professional 494 newfoundland and labrador studies, 32, 2 (2017) 1719-1726 John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal tools, throughout his career. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Catholic Archives 2002 to Completion - Hence 'Introductory Notes'

Catholic Archives i 2002 Number 22 THE JOURNAL OF The Catholic Archives Society CATHOLIC ARCHIVES NO 22 CONTENTS 2002 Introductory Notes New CAS Patrons 3 Birmingham Archdiocesan Archives J. SHARP 6 From Sight to Sound: Archival Evidence for English Catholic Music T.E. MUIR 10 The Archives of the Catholic Lay Societies II R. GARD 26 Dominican Congregation of St Catherine of Siena of Newcastle Natal S Africa Sr. E MURPHY O.P. 35 Oakford Domincans in England Sr. C. BROKAMP O.P. 40 The Congregation of the Sisters of St Anne Sr E. HUDSON S.S.A. 47 Archives of Holy Cross Abbey, Whitland, SA34 OGX, Wales, Cistercian Nuns Sr J. MOOR OSCO 52 Homily Idelivered at Hornby, July 15th 2001, on the occasion of the 150 Anniversary of the death of John Lingard P. PHILIPPS 54 Book Reviews 57 The Catholic Archives Society Conference, 2001 64 1 Introductory Notes Traditionally this page has been entitled 'Editorial notes'. Un fortunately the Editor has been unable to see Catholic Archives 2002 to completion - hence 'Introductory Notes'. Last year, Father Foster pointed out that he was presenting the first part of Father Joseph Fleming's study on archival theory and standards and promised the second part this year. This has been held over once again, this time not for reasons of space but for reasons of time. With the Editor unavailable, it was not possible for others to edit in such a way as to synchronise with the first part before sending the draft journal to the printers. Catholic Archives 2002 offers T. -

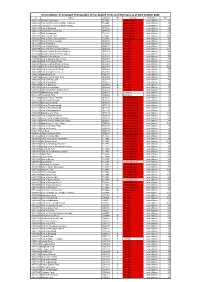

English Fords Statistics

Reconciliation of Geograph Photographs versus English Fords and Wetroads as at 03rd October 2020 Id Name Grid Ref WR County Submitter Hits 3020116 Radwell Causeway TL0056 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 37 3069286 Ford and Packhorse Bridge at Sutton TL2247 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 82 3264116 Gated former Ford at North Crawley SP9344 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 56 3020108 Ford at Farndish SP9364 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 52 3020123 Felmersham Causeway SP9957 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 37 3020133 Ford at Clapham TL0352 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 81 3020073 Upper Dean Ford TL0467 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 143 5206262 Ford at Priory Country ParK TL0748 B Bedfordshire John Walton 71 3515781 Border Ford at Headley SU5263 ü Berkshire John Walton 88 3515770 Ford at Bagnor SU5469 ü Berkshire John Walton 45 3515707 Ford at Bucklebury SU5471 ü Berkshire John Walton 75 3515679 Ford and Riders at Bucklebury SU5470 ü Berkshire John Walton 114 3515650 Byway Ford at Stanford Dingley SU5671 ü Berkshire John Walton 46 3515644 Byway Ford at Stanford Dingley SU5671 ü Berkshire John Walton 49 3492617 Byway Ford at Hurst SU7874 ü Berkshire John Walton 70 3492594 Ford ar Burghfield Common SU6567 ü Berkshire John Walton 83 3492543 Ford at Jouldings Farm SU7563 ü Berkshire John Walton 67 3492407 Byway Ford at Arborfield Cross SU7667 ü Berkshire John Walton 142 3492425 Byway Ford at Arborfield Cross SU7667 ü Berkshire John Walton 163 3492446 Ford at Carter's Hill Farm SU7668 ü Berkshire John Walton 75 3492349 Ford at Gardners Green SU8266 ü Berkshire John Walton -

Sakry I Sukcesja Święceń Biskupich Pasterzy Diecezji Mińskiej, Pińskiej I Drohiczyńskiej

Studia TeoloGiczne Białystok, Drohiczyn, Łomża 27(2009) Krzysztof R. Prokop SAKRY I SUKCESJA świĘceń BISKUPICH PASTERZY DIECEZJI mińSKIEJ, PińSKIEJ I DROHIczyńSKIEJ W opublikowanym w roku 2006 przez piszącego te słowa książkowym zbiorze życiorysów biskupów Mińska, Pińska oraz Drohiczyna nie poświę- cono z osobna uwagi problematyce sakr i sukcesji apostolskiej tychże hie- rarchów, jakkolwiek w każdym spośród szkiców biograficznych zamiesz- czono informacje na temat konsekracji danego członka katolickiego epi- skopatu, zaś w aneksie na końcu książki znalazły się stosowne schematy sukcesji1. Powyższy wzgląd, a nie mniej okoliczność, iż post factum uda- ło się dotrzeć do pewnych jeszcze świadectw źródłowych, pozwalających na uszczegółowienie dotychczas poczynionych w owym względzie usta- leń, skłania do pochylenia się nad tytułową tematyką i zaprezentowania jej w formie odrębnego artykułu, dzięki czemu na przyszłość nie będzie zachodziła konieczność poszukiwania rozproszonych informacji w rzeczo- nej materii w literaturze przedmiotu (w tym we wspomnianej wyżej edy- cji). Tak też w pierwszej kolejności dokonamy poniżej zebrania podstawo- wych informacji odnośnie do sakry każdego spośród interesujących nas hierarchów (data, miejsce, główny konsekrator, współkonsekratorzy), by następnie przyporządkować wszystkich tych biskupów do wyróżnianych w literaturze przedmiotu linii („rodzin”) sukcesji święceń. Całość wywo- dów zaopatrzona zostanie w zawarte w przypisach stosowne wskazania bi- bliograficzne, informujące o podstawie źródłowej tudzież o istniejących opracowaniach, w których mowa jest o danym fakcie, czego we wspo- minanej publikacji z roku 2006 zasadniczo brakowało (znalazły się tam 1 K.R. Prokop, Pasterze i rządcy diecezji mińskiej, pińskiej i drohiczyńskiej, Drohiczyn 2006 (wspomniane schematy sukcesji znajdują się tamże na s. 299–300). 361 Krzysztof R. Prokop jedynie zbiorcze zestawienia wydawnictw źródłowych i opracowań – w for- mie zamieszczonej na końcu bibliografii)2. -

MDA027 Gautrot Josephine Hymn

Australian Music Series – MDA027 A Josephine Hymn Teach Me Dearest Lord to Pray For Soprano and Organ Hobart - 1844 Joseph Gautrot France, c. 1783 – Sydney, 1854 Edited by Richard Divall Music Archive Monash University Melbourne 2 ! Information about the MUSIC ARCHIVE series Australian Music And other available works in the free digital series is available at http://artsonline.monash.edu.au/music-archive This edition may be used free of charge for private performance and study. It may be freely transmitted and copied in electronic or printed form. All rights are reserved for performance, recording, broadcast and publication in any audio format. © 2014 Richard Divall Published by MUSIC ARCHIVE OF MONASH UNIVERSITY Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music Monash University, Victoria, 3800, Australia ISBN 978-0-9925672-6-2 ISMN 979-0-9009642-6-7 The edition has been produced with generous assistance from the Australian Research Theology Foundation Marshall-Hall Trust ! 3 Introduction Joseph Gautrot is a fascinating and yet enigmatic figure. According to sources he led an adventurous life, and spent time in out of the way colonial outposts. He composed music seemingly of substance, and for ensembles normally associated with higher class music, yet despite this, we have only one work surviving by this active musician and prolific composer. Much of his life and professional activity has been thoroughly explored in Graeme Skinner’s important thesis on early Australian composition.1 More is found in his website of Australian composers, and the accompanying chronology of Australian composition.2 Both sources are important documents.3 The birth date of Joseph Gautrot is unknown, but there are various mentions of his early life and career in an obituary in Bell’s Life of 4 February 1854.4 In the obituary he was cited as being a member of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, probably as a musician, and was present during the Russian Campaign of 1812. -

North York Moors Local Plan

North York Moors Local Plan Infrastructure Assessment This document includes an assessment of the capacity of existing infrastructure serving the North York Moors National Park and any possible need for new or improved infrastructure to meet the needs of planned new development. It has been prepared as part of the evidence base for the North York Moors Local Plan 2016-35. January 2019 2 North York Moors Local Plan – Infrastructure Assessment, February 2019. Contents Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 6 2. Spatial Portrait ............................................................................................................................ 8 3. Current Infrastructure .................................................................................................................. 9 Roads and Car Parking ........................................................................................................... 9 Buses .................................................................................................................................... 13 Rail ....................................................................................................................................... 14 Rights of Way....................................................................................................................... -

Father Therry-100 Years On

Father Therry-100 years On Imprimatur: ✠ JUSTIN D. SIMONDS, Archiepiscopus Melburnensis. 5th June, 1964. Nihil Obstat: BERNARD O'CONNOR, Diocesan Censor. July 10, 1964 The Convict Cart Through the streets of Cork in 1818 there rumbled a wagon load of convicts. Bound for Botany Bay, the twenty or thirty prisoners were in irons on their way to the docks. A young priest stopped the driver and learnt of their destination. On the spur of the moment he ran into a neighbouring bookshop, bought a bundle of prayer books and threw them into the cart, vowing to follow his countrymen to the ends of the earth, if needed, to save their souls. In retrospect, that handful of books was the scattering of his first seeds of Catholicism in Australia, for the young priest was John Joseph Therry, secretary to Bishop Murphy of Cork. Such an act was typical of the warm-hearted and impulsive young man ordained only three years earlier. Born in the City of Cork in 1790, he was able to enjoy the luxury of a private tutor with his brothers, James and Stephen and his sister, Jane Anne, during his early years. As a seminarian at St. Patrick's College, Carlow, he seems to have been a thorough if not brilliant student. His family was hit by financial losses in those years. "The course of my college studies was interrupted at an early stage by family embarrassment," he wrote in 1819. At his own request he was ordained prematurely by the Archbishop of Dublin in 1815. Even before Father O'Flynn had sailed on his ill-fated mission to New South Wales, Father Therry had seriously considered volunteering for that mission field. -

Carlow College

- . - · 1 ~. .. { ~l natp C u l,•< J 1 Journal of the Old Carlow Society 1992/1993 lrisleabhar Chumann Seanda Chatharlocha £1 ' ! SERVING THE CHURCH FOR 200 YEARS ! £'~,~~~~::~ai:~:,~ ---~~'-~:~~~ic~~~"'- -· =-~ : -_- _ ~--~~~- _-=:-- ·.. ~. SPONSORS ROYAL HOTEL- 9-13 DUBLIN STREET ~ P,•«•11.il H,,rd ,,,- Qua/in- O'NEILL & CO. ACCOUNTANTS _;, R-.. -~ ~ 'I?!~ I.-: _,;,r.',". ~ h,i14 t. t'r" rhr,•c Con(crcncc Roonts. TRAYNOR HOUSE, COLLEGE STREET, CARLOW U • • i.h,r,;:, F:..n~ r;,,n_,. f)lfmt·r DL1nccs. PT'i,·atc Parties. Phone:0503/41260 F."-.l S,:r.cJ .-\II Da,. Phone 0503/31621. t:D. HAUGHNEY & SON, LTD. Jewellers, ·n~I, Fashion Boutique, Fuel Merchant. Authorised Ergas Stockist ·~ff 62-63 DUBLIN ST., CARLOW POLLERTON ROAD, CARLOW. Phone 0503/31367 OF CARLOW Phone:0503/31346 CIGAR DIVAN TULL Y'S TRAVEL AGENCY Newsagent, Confectioner, Tobacconist, etc. TULLOW STREET, CARLOW DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW Phone:0503/31257 Bring your friends to a musical evening in Carlow's unique GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA Music Lounge each Saturday and Sunday. Phone: 0503/27159. ST. MARY'S ACADEMY, SMYTHS of NEWTOWN CARLOW SINCE 1815 DEERPARK SERVICE STATION MICHAEL DOYLE Builders Providers, General Hardware Tyre Service and Accessories 'THE SHAMROCK", 71 TULLOW STREET, CARLOW DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. Phone 0503/31414 Phone:0503/31847 THOMAS F. KEHOE SEVEN OAKS HOTEL Specialist Livestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Far, Sales and Lettings,. Property and Est e Agent. Dinner Dances * Wedding Receptions * Private Parties Agent for the Irish Civil Ser- ce Building Society. Conferences * Luxury Lounge 57 DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW. Telephone 0503/31678, 31963. -

The Irish Catholic Episcopal Corps, 1657 – 1829: a Prosopographical Analysis

THE IRISH CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPS, 1657 – 1829: A PROSOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS VOLUME 1 OF 2 BY ERIC A. DERR THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR. THOMAS O’CONNOR NOVEMBER 2013 Abstract This study explores, reconstructs and evaluates the social, political, educational and economic worlds of the Irish Catholic episcopal corps appointed between 1657 and 1829 by creating a prosopographical profile of this episcopal cohort. The central aim of this study is to reconstruct the profile of this episcopate to serve as a context to evaluate the ‘achievements’ of the four episcopal generations that emerged: 1657-1684; 1685- 1766; 1767-1800 and 1801-1829. The first generation of Irish bishops were largely influenced by the complex political and religious situation of Ireland following the Cromwellian wars and Interregnum. This episcopal cohort sought greater engagement with the restored Stuart Court while at the same time solidified their links with continental agencies. With the accession of James II (1685), a new generation of bishops emerged characterised by their loyalty to the Stuart Court and, following his exile and the enactment of new penal legislation, their ability to endure political and economic marginalisation. Through the creation of a prosopographical database, this study has nuanced and reconstructed the historical profile of the Jacobite episcopal corps and has shown that the Irish episcopate under the penal regime was not only relatively well-organised but was well-engaged in reforming the Irish church, albeit with limited resources. By the mid-eighteenth century, the post-Jacobite generation (1767-1800) emerged and were characterised by their re-organisation of the Irish Church, most notably the establishment of a domestic seminary system and the setting up and manning of a national parochial system. -

C:\Users\User\Documents\Aaadocs

Vatican Archives of the Sacred Congregation "de Propaganda Fide" 1622-1846 vol. 6 CONGRESSI 1622-1836 PART 2 1800-30 [entries nos. 001-456] 219 220 Table of Contents of Part 2 225 Congressi, America Settentrionale (nos. 001-242) 325 Congressi, America Centrale (nos. 243-346) 365 Congressi, America Centrale, Miscellanee (nos. 347-348) 366 Congressi, America Antille (nos. 349-361) 371 Congressi, Anglia (nos. 362-395) 384 Congressi, Francia (nos. 396-398) 385 Congressi, Irlanda (nos. 399-411) 389 Congressi, Belgio Olanda (nos. 412-413) 390 Congressi, Missioni (nos. 414-425) 395 Congressi, Missioni, Miscellanee (nos. 426-437) 399 Congressi, Ministri (nos. 438-445) 402 Congressi, Sacra Congregazione (nos. 446-456) 221 222 ENTRIES 1800-31 (nos. 001-456) 223 224 ENTRIES ENTRY NUMBER: 001 SERIES: Congressi, America Settentrionale VOLUME: 2 (1792-1830) FOLIOS: 10rv-11rv. B: ff. 10v-11r LANGUAGE: Latin LOCATION: [Rome] DATE: [00 000 1801] AUTHOR: [Sacred Congregation "de Propaganda Fide"] RECIPIENT: [Sacred Congregation "de Propaganda Fide"] TYPE OF DOCUMENT: Memorandum DESCRIPTION: A report [probably a summary] on the bishopric of Québec. The diocese is said to be very large, extending "for 300 leagues and more past Québec." Its bishop is Pierre Denaut, his coadjutor Joseph-Octave Plessis. The seminary [Séminaire de Québec], formerly attached to the Foreign Missions [Séminaire des Missions-Étrangères], is now under the English regime and has Canadian [Lower Canadian] directors. The Sulpician Seminary of Montréal owns the island. Notes of the Sacred Congregation "de Propaganda Fide." REMARKS: Cross-references: Cal. 1800-30 IV 001 018-020 022, V 002 005, VI 001-002 005-012.