Hans Zimmer, Ridley Scott, and the Proper Length of the Gladius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pirates of the Caribbean

Music composed by Klaus Badelt and Hans Zimmer - arranged by Steven Verhaert The Pirates of The Caribbean For Brass Quintet Including the main themes "The Medallion Calls" , "The Black Pearl" and "He's A Pirate" from Walt Disney's "Pirates of the Caribbean" Allegro moderato q= 110 ° j > #3 ∑ ∑ Œ -œ 1st Trumpet in Bb & 4 œ œ œ™ -œ -œ œ œ >- >- >- > > >- >- #3 mf 2nd Trumpet in Bb & 4 ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ 3 Horn in F & 4 œ œœœ œ œ œ œ œœœ œ œ œ œ œœœ œ œ œ œ œœœ œœœ œ œ œœœ œœœ œ > >- > mf > > >-œ™ -œ œ -œ >- >-œ ? 3 -œ -œ J œ Trombone b4 ∑ ∑ Œ mf ? 3 ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ Œ ‰ Œ Tuba ¢ b4 j j j j j j j j j j j œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ mf 6 ° # >- >-™ j j & œ -œ œ -œ™ ‰ œ -œ œ -œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ ‰ j j‰ >- > > >- > > >- >- >- >- -œ >- -œ œ. œ. œ. œ. œ > > > >. # & ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ & œ œœœ œœœ œ j‰ Œ j ‰ j ‰ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œœœ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ œ œ œ œ j - >- -œ . œ. >- >-™ >-™ >- >- > >- > > > > >- >-œ œ œ >- >-œ œ œ œ #-œ œ >-œ >-™ n>-œ >- > ? œ œ J œ J œ œ. œ. œ. j j b ‰ ‰ œ œ ‰ >. ? j‰ Œ ‰ Œ j‰ ‰ ¢ b œ œ œ j œ œœœ œ œ œœœ œœ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ The Medallion Calls (from The Pirates of The Caribbean) Words and Music by Klaus Badelt, Hans Zimmer and Ramin Djawadi © 2004 Walt Disney Music (USA) Co, USA administered by Artemis Muziekuitgeverij B.V., The Netherlands This arrangement © 2014 Walt Disney Music (USA) Co, USA administered by Artemis Muziekuitgeverij B.V., The Netherlands Warner/Chappell Artemis Music Ltd, London W8 5DA Reproduced by permission of Faber Music Ltd All Rights Reserved. -

2Cellos Take Fans to the Movies with New Album Score Accompanied by the London Symphony Orchestra

2CELLOS TAKE FANS TO THE MOVIES WITH NEW ALBUM SCORE ACCOMPANIED BY THE LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALBUM AVAILABLE MARCH 17, 2017 BAND KICKS OFF WORLD TOUR IN SUMMER 2017 2CELLOS, music’s most electric and dynamic instrumental duo, go to the movies for their new Portrait/Sony Music Masterworks album Score, available on March 17, 2017. Bringing 2CELLOS’ game-changing sound and style to the most popular melodies ever written for classic and contemporary movies and television, Score will be supported by a world tour, kicking off with its U.S. leg in July 2017. An international sensation since their unique video version of Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal” rocked YouTube with millions of hits in 2011, the Croatian cellists Luka Šulić and Stjepan Hauser have created three high-energy albums for Sony Music Masterworks. Score finds them exploring a more traditional sound-world. Joining them here – to provide the ideal aural backdrop to their virtuosity – is the London Symphony Orchestra, with conductor/arranger Robin Smith at the helm. Šulić and Hauser also co-produced Score with Nick Patrick (Elvis Presley/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Russell Watson, Il Divo, Plácido Domingo). “We love movie music! This album represents some of our favorite pieces of music by our favorite film composers. Having the opportunity to arrange them for cello whilst working with the world class London Symphony Orchestra has been a dream come true,” says Stjepan. The album opens with an arrangement of Ramin Djawadi’s melodies that score Game of Thrones, culminating in the bold Main Title theme, in which the stirring sound of cellos announces each of what may be the most eagerly awaited episodes in contemporary television. -

Compositori Da Oscar

COMPOSITORI DA OSCAR Proposte di ascolto di compositori che con la loro musica hanno fatto la storia del cinema e consigli di visone di film premi Oscar per la colonna sonora CD AUDIO Anne Dudley, The full monty. Music from the motion picture soundtrack (1997), RCA Victor: FOX searchlight [CD] MUSICA COLONNE-SONORE FUL Max Goberman, West side story (1998), nell'interpretazione di New York Philarmonic, Leonard Bernstein, Sony Classical: Columbia: Legacy [CD] MUSICA COLONNE-SONORE WES Ennio Morricone, Per un pugno di dollari. Colonna sonora originale (1964), BMG [CD] MUSICA COLONNE-SONORE PER Ennio Morricone, Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo. Original motion picture soundtrack (1966), GMD [CD] MUSICHE COLONNE-SONORE BUO Nicola Piovani, Musiche per i film di Nanni Moretti. Caro diario, Palombella rossa, La messa è finita (1999), Emergency Music Italy: Virgin [CD] MUSICA COLONNE-SONORE MUS Steven Price, Gravity. Original motion picture soundtrack (2013), Silva Screen Records [CD] MUSICA COLONNE-SONORE GRA Nino Rota, La strada, Le notti di Cabiria. Original soundtracks (1992), Intermezzo, Biem, Siae, [CD] MUSICA COLONNE-SONORE STR Rota, Nino (et al), The Godfather. Trilogy 1- 2- 3 (1990), Silva Screen Records [CD] MUSICA COLONNE-SONORE GOD Ryuichi Sakamoto, The sheltering sky. Music from the original motion picture soundtrack (1990), Virgin [DVD] MUSICA COLONNE-SONORE SHE Ryuichi Sakamoto, The Last Emperor (1987), Virgin Records [CD] MUSICA COLONNE-SONORE LAS Vangelis, Blade runner (1982), WEA [CD] MUSICA COLONNE-SONORE BLA John Williams, The -

Contemporary Film Music

Edited by LINDSAY COLEMAN & JOAKIM TILLMAN CONTEMPORARY FILM MUSIC INVESTIGATING CINEMA NARRATIVES AND COMPOSITION Contemporary Film Music Lindsay Coleman • Joakim Tillman Editors Contemporary Film Music Investigating Cinema Narratives and Composition Editors Lindsay Coleman Joakim Tillman Melbourne, Australia Stockholm, Sweden ISBN 978-1-137-57374-2 ISBN 978-1-137-57375-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57375-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931555 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

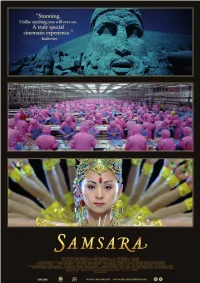

Samsara Persmap

SAMSARA van Ron Fricke & Mark Magidson Release: 19 december 2013 2011 | 100 minuten | Super 70 mm Panavision | Dolby Digital Samsara, een film van Ron Fricke (Koyaanisqatsi) en Mark Magidson die eerder samen de bekroonde films Baraka (1992) en Chronos (1985) maakten, is een ongekend zintuigelijke ervaring. Samsara is Sanskriet voor ‘het eeuwig draaiende rad van het leven’ en is het vertrekpunt van de filmmakers. Gefilmd over een periode van bijna 5 jaar en in 25 landen toont Samsara ons heilige plaatsen, rampgebieden, industriële landschappen en natuurwonderen. Samsara is een film zonder dialoog en beschrijvende teksten en is daardoor niet een traditionele documentaire maar een werk dat de toeschouwer inspireert, geholpen door de sublieme beelden en zinnelijke muziek die het oude en het moderne vermengt. Hierdoor nodigt Samsara ons uit om onze eigen interpretatie te geven aan deze prikkelende reis over de wereld. De film is geheel op 70 mm formaat gefilmd: extra scherpe details en intense kleuren. Samsara is vanaf 19 december te zien in de bioscoop en in een aantal zalen in een 70 mm projectie. SAMSARA wordt in Nederland gedistribueerd door ABC/Cinemien. Beeldmateriaal kan gedownload worden vanaf: www.cinemien.nl/pers of vanaf www.filmdepot.nl Voor meer informatie: ABC/ Cinemien | Anne Kervers | [email protected] | 0616274537 | 020-5776010 (Cinemien) Directed and photographed by Ron Fricke ( links ) Produced by Mark Magidson ( rechts ) Edited by Ron Fricke, Mark Magidson Original Music composed by Michael Stearns Original Music composed by Lisa Gerrard, Marcello De Francisi Concept and treatment written by Ron Fricke, Mark Magidson Musical Direction by Michael Stearns, Mark Magidson Production Coordinator Michelle Peele Ron Fricke Ron Fricke is a meticulous filmmaker who has mastered a wide range of skills. -

Teaching World History with Major Motion Pictures

Social Education 76(1), pp 22–28 ©2012 National Council for the Social Studies The Reel History of the World: Teaching World History with Major Motion Pictures William Benedict Russell III n today’s society, film is a part of popular culture and is relevant to students’ as well as an explanation as to why the everyday lives. Most students spend over 7 hours a day using media (over 50 class will view the film. Ihours a week).1 Nearly 50 percent of students’ media use per day is devoted to Watching the Film. When students videos (film) and television. With the popularity and availability of film, it is natural are watching the film (in its entirety that teachers attempt to engage students with such a relevant medium. In fact, in or selected clips), ensure that they are a recent study of social studies teachers, 100 percent reported using film at least aware of what they should be paying once a month to help teach content.2 In a national study of 327 teachers, 69 percent particular attention to. Pause the film reported that they use some type of film/movie to help teach Holocaust content. to pose a question, provide background, The method of using film and the method of using firsthand accounts were tied for or make a connection with an earlier les- the number one method teachers use to teach Holocaust content.3 Furthermore, a son. Interrupting a showing (at least once) national survey of social studies teachers conducted in 2006, found that 63 percent subtly reminds students that the purpose of eighth-grade teachers reported using some type of video-based activity in the of this classroom activity is not entertain- last social studies class they taught.4 ment, but critical thinking. -

Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films Merle Kenneth Peirce Rhode Island College

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview and Major Papers 4-2009 Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films Merle Kenneth Peirce Rhode Island College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Peirce, Merle Kenneth, "Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films" (2009). Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview. 19. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/etd/19 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRANSGRESSIVE MASCULINITIES IN SELECTED SWORD AND SANDAL FILMS By Merle Kenneth Peirce A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Individualised Masters' Programme In the Departments of Modern Languages, English and Film Studies Rhode Island College 2009 Abstract In the ancient film epic, even in incarnations which were conceived as patriarchal and hetero-normative works, small and sometimes large bits of transgressive gender formations appear. Many overtly hegemonic films still reveal the existence of resistive structures buried within the narrative. Film criticism has generally avoided serious examination of this genre, and left it open to the purview of classical studies professionals, whose view and value systems are significantly different to those of film scholars. -

GLADIATOR by David Franzoni Revisions by John Logan SECOND

GLADIATOR by David Franzoni Revisions by John Logan SECOND DRAFT October 22, 1998 FADE IN: EXT. FOREST - DAY Germania. The far reaches of the Roman Empire. Winter 180 A.D. Incongruously enough, the first sound we hear is a beautiful tenor voice. Singing. A boy's voice. CREDITS as we hear the haunting song float through dense forests. We finally come to a rough, muddy road slashing through the forest. On the road a GERMAN PEASANT FATHER is herding along three sickly looking cows. His two SONS are with him. His youngest son sits on one of the cows and sings a soft, plaintive song. They become aware of another sound behind them on the road -- the creak of wood, the slap of metal on leather. The Father immediately leads his cattle and his sons off the road. They stand-still, eyes down: the familiar posture of subjugated peoples throughout history. A wagon train rumbles past them. Three ornate wagons followed by a mounted cohort of fifty heavily-armed PRAETORIAN GUARDS. The young boy dares to glance up at the passing Romans. His eyes burn with hatred. INT. WAGON - DAY Mist momentarily obscures a man's face. Frozen breath. The man is in his 20's, imperious and handsome. He is swathed in fur, only his face exposed. He is COMMODUS. He glances up. COMMODUS Do you think he's really dying? The woman across from him returns his gaze evenly. She is slightly older, beautiful and patrician. A formidable woman. She is LUCILLA. LUCILLA He's been dying for ten years. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

MADE in HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED by BEIJING the U.S

MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence 1 MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION 1 REPORT METHODOLOGY 5 PART I: HOW (AND WHY) BEIJING IS 6 ABLE TO INFLUENCE HOLLYWOOD PART II: THE WAY THIS INFLUENCE PLAYS OUT 20 PART III: ENTERING THE CHINESE MARKET 33 PART IV: LOOKING TOWARD SOLUTIONS 43 RECOMMENDATIONS 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 53 ENDNOTES 54 Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ade in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing system is inconsistent with international norms of Mdescribes the ways in which the Chinese artistic freedom. government and its ruling Chinese Communist There are countless stories to be told about China, Party successfully influence Hollywood films, and those that are non-controversial from Beijing’s warns how this type of influence has increasingly perspective are no less valid. But there are also become normalized in Hollywood, and explains stories to be told about the ongoing crimes against the implications of this influence on freedom of humanity in Xinjiang, the ongoing struggle of Tibetans expression and on the types of stories that global to maintain their language and culture in the face of audiences are exposed to on the big screen. both societal changes and government policy, the Hollywood is one of the world’s most significant prodemocracy movement in Hong Kong, and honest, storytelling centers, a cinematic powerhouse whose everyday stories about how government policies movies are watched by millions across the globe. -

Aesthetics of the Motion Picture Soundtrack Columbia College, Chicago Spring 2014 – Section 01 – Pantelis N

Aesthetics of the Motion Picture Soundtrack Columbia College, Chicago Spring 2014 – Section 01 – Pantelis N. Vassilakis Ph.D. http://lms.colum.edu Course # / Section 43-2410 / 01 Credits 3 hours Class time / place Thursday 12:30 – 3:20 p.m. 33 E. Congress Ave., Room LL18 (Lower Level – Control Room C) Course Site On MOODLE http://lms.colum.edu Instructor Pantelis N. Vassilakis, Ph.D. Phone Office: 312-369-8821 – Cell: 773-750-4874 e-mail / web [email protected] / http://www.acousticslab.org Office hours By appointment; Preferred mode of Communication: email Pre-requisites 52-1152 “Writing and Rhetoric II” (C or better) AND 43-2420 “Audio for Visual Media I” OR 24-2101 “Post Production Audio I” OR 43-2310 “Psychoacoustics” INTRODUCTION During the filming of Lifeboat, composer David Raksin was told that Hitchcock had decided against using any music. Since the action took place in a boat on the open sea, where would the music come from? Raksin reportedly responded by asking Hitchcock where the cameras came from. This course examines film sound practices, focusing on cross-modal perception and cognition: on ways in which sounds influence what we “see” and images influence what we “hear.” Classes are conducted in a lecture format and involve multimedia demonstrations. We will be tackling the following questions: • How and why does music and sound effects work in films? • How did they come to be paired with the motion picture? • How did film sound conventions develop and what are their theoretical, socio-cultural, and cognitive bases? • How does non-speech sound contribute to a film’s narrative and how can such contribution be creatively explored? Aesthetics of the Motion Picture Soundtrack – Spring 2014 – Section 01 Page 1 of 12 COURSE DESCRIPTION & OBJECTIVES Course examines Classical Hollywood as well as more recent film soundtrack practices, focusing on the interpretation of film sound relative to ‘expectancy’ theories of meaning and emotion. -

Contemporary Film Music

Edited by LINDSAY COLEMAN & JOAKIM TILLMAN CONTEMPORARY FILM MUSIC INVESTIGATING CINEMA NARRATIVES AND COMPOSITION Contemporary Film Music Lindsay Coleman • Joakim Tillman Editors Contemporary Film Music Investigating Cinema Narratives and Composition Editors Lindsay Coleman Joakim Tillman Melbourne, Australia Stockholm, Sweden ISBN 978-1-137-57374-2 ISBN 978-1-137-57375-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57375-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931555 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made.