Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, SJ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Life and Literature of the Southwest REVISED and ENLARGED in BOTH KNOWLEDGE and WISDOM J. FRANK DOBIE DALLAS . 1952

Guide to Life and Literature of the Southwest REVISED AND ENLARGED IN BOTH KNOWLEDGE AND WISDOM J. FRANK DOBIE DALLAS . 1952 SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY PRESS _Not copyright in 1942 Again not copyright in 1952_ Anybody is welcome to help himself to any of it in any way LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 52-11834 S.M.U. PRESS Contents A Preface with Some Revised Ideas 1. A Declaration 2. Interpreters of the Land 3. General Helps 4. Indian Culture; Pueblos and Navajos 5. Apaches, Comanches, and Other Plains Indians 6. Spanish-Mexican Strains 7. Flavor of France 8. Backwoods Life and Humor 9. How the Early Settlers Lived 10. Fighting Texians 11. Texas Rangers 12. Women Pioneers 13. Circuit Riders and Missionaries 14. Lawyers, Politicians, J.P.'s 15. Pioneer Doctors 16. Mountain Men 17. Santa Fe and the Santa Fe Trail 18. Stagecoaches, Freighting 19. Pony Express 20. Surge of Life in the West 21. Range Life: Cowboys, Cattle, Sheep 22. Cowboy Songs and Other Ballads 23. Horses: Mustangs and Cow Ponies 24. The Bad Man Tradition 25. Mining and Oil 26. Nature; Wild Life; Naturalists 27. Buffaloes and Buffalo Hunters 28. Bears and Bear Hunters 29. Coyotes, Lobos, and Panthers 30. Birds and Wild Flowers 31. Negro Folk Songs and Tales 32. Fiction-Including Folk Tales 33. Poetry and Drama 34. Miscellaneous Interpreters and Institutions 35. Subjects for Themes Index to Authors and Titles Illustrations Indian Head by Tom Lea, from _A Texas Cowboy_ by Charles A. Siringo (1950 edition) Comanche Horsemen by George Catlin, from _North American Indians_ Vaquero by Tom Lea, from _A Texas Cowboy_ by Charles A. -

Densmore Hotel, Kansas City, Missouri, February 3, 1933. Mr

Densmore Hotel, Kansas City, Missouri, February 3, 1933. Mr. Stanley Vestal, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma. My dear Mr. Vestal:- In the morning Kansas City Star (Times) I read with interest an excerpt from your biography of Sitting Bull. I should like to have the book but the publisher was not indicated. My interest in Sitting Bull---in any authentic account of him---arises from the fact that I have spent a good deal of time in The Sioux country and last swamer painted some portraits of the survivors of the Custer battle among which were some relatives and members of the Sitting Bull faction. I talked at length with some of these Sioux, through the official interpreter at Fort Yates, about the Custer 'massacre' and about Sitting Bull and other leaders. There is and likely always will be controversy about some details of the Custer battle, since no active participant survived; but I found a remarkable unanimity regarding, the status of Sitting Bull and his part in the battle. He was not--- it is agreed---an active participant in the battle of the Little Big Horn or in any other battle of any note.* Gall, Two Moons and Crazy Horse were the real leaders and Gall was the greatest tactician of them all. Sitting Bull, so far as I could learn, was an agitatorfand a seer, and a leader in those fields. I was, by the way, on the spot where his cabin stood and where he was killed by Indian police under the direction of Red Tomahawk who is said to have fired the fatal shot. -

The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative Written by Shirley E

THE EMIGRANT MÉTIS OF KANSAS: RETHINKING THE PIONEER NARRATIVE by SHIRLEY E. KASPER B.A., Marshall University, 1971 M.S., University of Kansas, 1984 M.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1998 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2012 This dissertation entitled: The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative written by Shirley E. Kasper has been approved for the Department of History _______________________________________ Dr. Ralph Mann _______________________________________ Dr. Virginia DeJohn Anderson Date: April 13, 2012 The final copy of this dissertation has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii ABSTRACT Kasper, Shirley E. (Ph.D., History) The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Ralph Mann Under the U.S. government’s nineteenth century Indian removal policies, more than ten thousand Eastern Indians, mostly Algonquians from the Great Lakes region, relocated in the 1830s and 1840s beyond the western border of Missouri to what today is the state of Kansas. With them went a number of mixed-race people – the métis, who were born of the fur trade and the interracial unions that it spawned. This dissertation focuses on métis among one emigrant group, the Potawatomi, who removed to a reservation in Kansas that sat directly in the path of the great overland migration to Oregon and California. -

Michigan, Watersmeet

Guide to Catholic-Related Records in the Midwest about Native Americans See User Guide for help on interpreting entries Archdiocese of St. Louis pub.1984/rev.2003-2017 MISSOURI, ST. LOUIS Jesuits, Society of Jesus, Central Jesuit Archives M-113 4511 West Pine Boulevard St. Louis, Missouri 63108 Phone 314-361-7765 http://jesuitarchives.org/ Hours: By appointment only, Monday-Friday, 8:30-11:45, 12:45-4:30 Access: No restrictions Copying facilities: Yes History: In 1997, to better serve the Chicago, Detroit, Missouri, and Wisconsin Provinces, these four provinces of the Society of Jesus combined their archival holdings and established the Central Jesuit Archives in St. Louis (initially known as the Midwest Jesuit Archives). However, per previously established agreements, most records pertaining to the Native American ministries of the Wisconsin Province remained at, and continue to be transferred to, Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. History of the Chicago Province The Chicago Jesuit Province was established in 1928. From St. Isaac Jogues Church, Sault Sainte Marie, Jesuits from the Chicago Province evangelized Ojibwa Indians of the eastern portion of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, 1947- 1955. History of the Detroit Province The Detroit Jesuit Province was established in 1955 from portions of the Chicago Province. From St. Isaac Jogues Church, Sault Sainte Marie, Jesuits from the Detroit Province evangelized Ojibwa Indians of the eastern portion of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, 1955-ca. 1995. History of the Missouri Province and the Missouri and Rocky Mountain Missions The Jesuit Missouri Province was established in 1863. It succeeded the Missouri Mission (established, 1823), which along with the Rocky Mountain Mission, were administered by the Maryland Province. -

The Potawatomi Mission of Council Bluffs

CHAPTER XIII THE POTAWATOMI MISSION OF COUNCIL BLUFFS § I THE POTAWATOMI The earliest known habitat of the Potawatomi was the lower Michigan peninsula Driven thence by Iroquois invaders, they settled on and about the islands at the mouth of Green Bay, Lake Michigan, where they were met in 1634 by Jean Nicolet, reputed the first white man to reach Wisconsin. Later they moved south, displacing the Miami and occupying both shores of Lake Michigan from between about Manitowoc on the west and Grand River on the east and settling southward as far as the Wabash Their lands comprised territory in Wisconsin, Illinois and Michigan, with some fifty villages, including those on the sites of Milwaukee, Chicago, and Grand Rapids 1 Of Algonkin stock, the Potawatomi were blood-relations of the Ottawa and Ojibway or Chippewa, with whom they appear to have formed at one time a single tribe - The Potawatomi ("fire-makers," "people of the fire-place"), may thus owe their name to the circum stance that they separated from the other two tribes and built a new "fire," which in Indian parlance is to set up as an independent tribe They were in the main hunters and fishers, tilling the ground but sparingly and this only for a meagre harvest of maize They were, moreover, a fighting race and as a consequence frequently in conflict with the whites and with the other tribes They supported the French against the British in the great struggle between the two powers for 1 James Mooney in Catholic Encyclofedia, 12 320 The spelling of Indnn tribal names, except in cited -

Books on West and Southwest Suggested for High School Libraries of the Area

BOOKS ON WEST AND SOUTHWEST SUGGESTED FOR HIGH SCHOOL LIBRARIES OF THE AREA Compiled by J. Frank Dobie A few of the titles that follow will not be interesting to the average pupil. That does not prevent their being important books, usuable by the best pupils and their teachers. My idea is to steer teaching and reading on the plus side rather than on the minus side. Intellect is never stimulated by mediocrity. If education does not elevate taste, what is the point of pretending at it? I know from experience that most of these books have been read by people of high school age. Many good books are out of print and are procurable only through dealers in out-of-print books, often at advanced prices. It does not seem advisable to list such here. Unless otherwise indicated, the publisher of each book listed can be found by using the Index in my Guide To Life and Literature of the South west and then referring to the page indicated. Any book dealer of consequence knows how to find any book kept in print by an established publisher. Andy Adams, The Log of a Cowboy (Houghton, Boston); Why the Chisholm Trail Forks (edited by Wilson Hudson, Univ. of Texas Press, Austin) Mary Austin, One Smoke Stories; The Land of Little Rain (Houghton, Boston) Mody C. Boatright, The Sky Is My Tipi. This is one of numerous publications of the Texas Folklore Society edited by Boatright and others. It contains vari ous Indian folk tales. Recent among these publications is Mesquite and Willow, which includes a number of Mexican folk tales, notably a collection by Riley Aiken. -

The Kickapoo Mission

CHAPTER XII THE KICKAPOO MISSION § I THE INDIAN MISSION "It was the Indian mission above everything else that brought us to Missouri and it is the principal point in the Concordat " x The words are those of Father Van Quickenborne and express the idea that was uppermost in his mind during the fourteen years of his strenuous activity on the frontier With a singleness of purpose that never wavered he sought to inaugurate resident missionary enterprise among the Indians as the real objective of the Jesuits of the trans-Mississippi West In a document presently to be cited, which bears the caption "Reasons for giving a preference to the Indian Mission before any other," he detailed the weighty considerations that made it imperative for the Society of Jesus to put its hand to this apostolic work It was primarily for the conversion of the Indians that the Society had been established in Missouri, it was with a view to realizing this noble pur pose that pecuniary aid had been solicited and obtained from benefac tors in Europe, and the tacit obligation thus incurred, to say nothing of the duty explicitly assumed in the Concordat, could be discharged only by setting up a mission in behalf of one or more of the native American tribes Even the new college in St Louis commended itself to the eager Van Quickenborne chiefly as a preparatory step to what was to him the more important enterprise of a missionary center among the Indians "All these things come by reason of the Indian mission," he wrote in November, 1828, to the Maryland superior, Dzierozynski, -

The Jesuits of the Middle United States

The Jesuits of the Middle United States by GILBERT J. GARRAGHAN, S.J., Ph.D. RESEARCH PROFESSOR OF HISTORY INSTITUTE OF JESUIT HISTORY LOYOLA UNIVERSITY, CHICAGO IN THREE VOLUMES VOLUME II CHICAGO LOYOLA UNIVERSITY PRESS 1984 Smpntm Potegf WILLIAM M MAGFE, SJ / Provincial, Chicago Provinie Jfttljil &b&tat ARTHUR J SCANLAN, STD Censor Librorum imprimatur ^PATRICK CARDINAL HAYES Archbishop of New York lugust I 1938 © 1984 Loyola University Press ISBN 0-8294-0445-7 ORIGINALLY PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY J J LITTLE AND IVES COMPANY, NEW YORK CONTENTS PART THREE {continued) JESUIT GROWTH IN THE MIDDLE WEST THE FIFTIES AND SIXTIES CHAPTER XIX THE RESIDENCES § i Piiochi il residences and their scope, I § 2 Washington m Missouri, 8 § 3 St Joseph's residence, St Louis, 25 § 4 Chilhcothe in Ohio, 35 § 5 Teirc Haute in Indiana, 37 § 6 Minor residences, 41 CHAPTER XX THE MINISTRY OF THE EXERCISES § I The Spiritual Fxercises and retreats, 4 8 § 2 F lanus Xavicr Wcnmgci, 53 § 3 German rural missions, 65 §4 English pirochnl missions, 69 § 5 Arnold Damen and his associates, 77 CHAPTER XXI LITERARY WORK RELATIONS WII H HIERARCHY AND SISTERHOODS § I The ministry of the pen, 103 § 2 Relations with the hierarchy, 112 § 3 Jesuit nominations to the episcopacy, 117 §4 Bishop Van de Veldc, 129 § 5 Bishop Carrell, 138 § 6 Relations with sisterhoods, 141 CHAPTER XXII THE JESUITS AND THE CIVIL WAR § i Viewpoints and reactions, 147 § 2 The draft, 159 § 3 Incidents and misadventures, 164 § 4 Aftermath of the war, 167 PART FOUR THE INDIAN MISSIONS CHAPTER -

The Centennial of “The Trail of Death” Irvingmckm on September 4, 1838, the Last Considerable Body of Indians in Indiana Was Forcibly Removed

The Centennial of “The Trail of Death” IRVINGMcKm On September 4, 1838, the last considerable body of Indians in Indiana was forcibly removed. The subsequent emigration of these Indians to the valley of the Osage River in Kansas has been appropriately named “The Trail of Death” by Jacob P. Dunn.l An article by Benjamin F. Stuart deal- ing with the removal of Menominee and his tribe, and Judge William Polke’s journal^' tell a vital part of the story.* In addition there are two monuments at Twin Lakes, Marshall County, that mark the scene of this removal. One is a statue of a conventional Indian upon a lofty pedestal with the following inscription : In Memory of Chief Menominee And His Band of 859 Pottawattomie Indians Removed From This Reservation Sept. 4, 1838 By A Company of Soldiers Under Command of General John Tipton Authon’zed By Governor David Wallace. Immediately below the above historical matter, the fol- lowing 2s inscribed: Governor of Indiana J. Frank Hanly Author of Law Representative Daniel McDonald, Plymouth Trustees Colonel A. F. Fleet, Culver Colonel William Hoynes, Notre Dame Charles T. Mattingly, Plymouth Site Donated By John A. McFarlin 1909 The second memorial is a tableted rock a quarter of a mile away from the first, at the northern end of the larger of the Twin Lakes, which marks the location of an old In- dian chapel. The inscription reads : Site of Menominee Chapel Pottawattomie Indian Church at 1 True Zndian Stories (Indianapolis, 1909). 237. ’ Stuart, “The Deportation of Menominee and His Tribe of Pottawattomie Indians.” Indiana Mawine of History (Septemher, 1922). -

Missions Among the Kickapoo and Osage in Kansas, 1820-1860

MISSIONS AMONG THE KICKAPOO AND OSAGE IN KANSAS, 1820-1860 by Willis Glenn Jackson A. B., Transylvania College, 1953 B. D,, The College of the Bible, 1956 1^^ A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OT ARTS Department of History KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1965 Ti -^'"^ TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE i CHAPTER I PERIOD BEFORE MISSIONS 1 CHAPTER II PRELUDES FOR MISSION ESTABLISHMENT 27 CHAPTER III PERIOD OF OPTIMISM 46 CHAPTER IV PERIOD OF DOUBT 65 CHAPTER V PERIOD OF WHHDRAWAL 92 CHAPTER VI CONCLUSIONS 103 BIBLIOGRAPHY 116 PREFACE To compare missions among the Kickapoo and the Osage presented two major problems. The first was finding adequate source material. Fortunately, the Kansas State Historical Society in Topeka had microfilm copies of the Kickapoo Missionary Papers originally collected by the Presbyterian Historical Society at Philadelphia, complete sets of the Missionary Herald , Annual Reports of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, and the Annual Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, A microfilm copy of the Christian Advocate and Zion's Herald was also available at the Kansas State Historical Library. At St. Mary's College, I found microfilm copies of many of the letters and writings of Father Paul Mary Ponziglione, a Catholic Osage missionary. The originals can be found in the Jesuit Archives In St. Louis. Besides these sources, the Kansas State Historical Society Collec- tions printed numerous articles about Indians and missions in Kansas. Three of these articles (a history of Methodist missions by J. J. Lutz, a personal testimony by a Methodist Kickapoo missionary, and collected letters of Methodist missionaries) were especially helpful. -

Potawatomi Indians of the West: Origins of the Citizen Band

This dissertation has been 61-3062 microfilmed exactly as received MURPHY, Joseph Francis, 1910— POTAWATOMI INDIANS OF THE WEST: ORIGINS OF THE CITIZEN BAND. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1961 History, archaeology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Joseph Francis Murphy 1961 THE UNIVERSITY OF OKIAHOMA. GRADUATE COLLEGE POTAWATOMI INDIANS OF THE WEST ORIGINS OF THE CITIZEN BAND A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY JOSEPH FRANCIS MURPHY Norman, Oklahoma 1961 POTAWATOMI INDIANS OF THE WEST: ORIGINS OF THE CITIZEN BAND APPROVED BY DISSERTATION COMMITTEE ACKNOWLEDGMENT It is with the deepest sense of gratitude that the àüthdr'"âcknowledges the assistance of Dr. Donald J. Berthrong, Department of History, University of Oklahoma, who gave so unsparingly of his time in directing all phases of the prep aration of this dissertation. The other members of the Dissertation Committee, Dr. Gilbert C. Fite, Dr. W. Eugene Hollon, Dr. Arrell M. Gibson, and Dr. Robert E. Bell were also most kind in performing their services during a very busy season of the year. Many praiseworthy persons contributed to the success of the period of research. Deserving of special mention are: Miss Gladys Opal Carr, Library of the University of Oklahoma; Mrs. 0. C. Cook, Mrs. Relia Looney, and Mrs, Dorothy Williams, all of the Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma Çity; Mrs. Lela Barnes and M r . Robert W. Richmond of the Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka; and Father Augustin Wand, S. J., St. Mary's College, St. Marys, Kansas. -

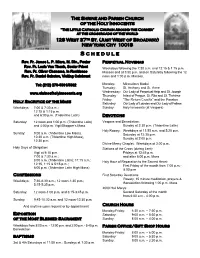

Schedule Rev

The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents “The Little Catholic Church Around the Corner” at the crossroads of the world 128 West 37th St. (Just West of Broadway) New York City 10018 Founded 1866 Schedule Rev. Fr. James L. P. Miara, M. Div., Pastor Perpetual Novenas Rev. Fr. Louis Van Thanh, Senior Priest Weekdays following the 7:30 a.m. and 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. Rev. Fr. Oliver Chanama, In Residence Masses and at 5:50 p.m. and on Saturday following the 12 Rev. Fr. Daniel Sabatos, Visiting Celebrant noon and 1:00 p.m. Masses. Tel: (212) 279-5861/5862 Monday: Miraculous Medal Tuesday: St. Anthony and St. Anne www.shrineofholyinnocents.org Wednesday: Our Lady of Perpetual Help and St. Joseph Thursday: Infant of Prague, St. Rita and St. Thérèse Friday: “The Return Crucifix” and the Passion Holy Sacrifice of the Mass Saturday: Our Lady of Lourdes and Our Lady of Fatima Weekdays: 7:00 & 7:30 a.m.; Sunday: Holy Innocents (at Vespers) 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Devotions Saturday: 12 noon and 1:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Vespers and Benediction: and 4:00 p.m. Vigil/Shopper’s Mass Sunday at 2:30 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Holy Rosary: Weekdays at 11:55 a.m. and 5:20 p.m. Sunday: 9:00 a.m. (Tridentine Low Mass), Saturday at 12:35 p.m. 10:30 a.m. (Tridentine High Mass), Sunday at 2:00 p.m. 12:30 p.m. Divine Mercy Chaplet: Weekdays at 3:00 p.m.