The Regulation of Commodity Options

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kicking the Bucket Shop: the Model State Commodity Code As the Latest Weapon in the State Administrator's Anti-Fraud Arsenal, 42 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 42 | Issue 3 Article 6 Summer 6-1-1985 Kicking the Bucket Shop: The oM del State Commodity Code as the Latest Weapon in the State Administrator's Anti-Fraud Arsenal Julie M. Allen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation Julie M. Allen, Kicking the Bucket Shop: The Model State Commodity Code as the Latest Weapon in the State Administrator's Anti-Fraud Arsenal, 42 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 889 (1985), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol42/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KICKING THE BUCKET SHOP: THE MODEL STATE COMMODITY CODE AS THE LATEST WEAPON IN THE STATE ADMINISTRATOR'S ANTI-FRAUD ARSENAL JuIE M. ALLEN* In April 1985, the North American Securities Administrators Association adopted the Model State Commodity Code. The Model Code is designed to regulate off-exchange futures and options contracts, forward contracts, and other contracts for the sale of physical commodities but not exchange-traded commodity futures contracts or exchange-traded commodity options. Specif- ically, the Model Code addresses the problem of boiler-rooms and bucket shops-that is, the fraudulent sale of commodities to the investing public. -

Commodities Litigation: the Impact of RICO

DePaul Law Review Volume 34 Issue 1 Fall 1984 Article 3 Commodities Litigation: The Impact of RICO Michael S. Sackheim Francis J. Leto Steven A. Friedman Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Michael S. Sackheim, Francis J. Leto & Steven A. Friedman, Commodities Litigation: The Impact of RICO , 34 DePaul L. Rev. 23 (1984) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol34/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMODITIES LITIGATION: THE IMPACT OF RICO Michael S. Sackheim* Francis J. Leto** Steven A. Friedman*** INTRODUCTION The number of private actions commenced against commodities brokers and other professionals in the futures area has increased dramatically in the last few years. Although these lawsuits primarily have been based on viola- tions of the Commodities Exchange Act (CEAct),' the complaints have fre- quently included allegations that the federal Racketeering Influenced and Cor- rupt Organization Act (RICO)2 was also violated by the subject defendents. In invoking the racketeering laws, the plaintiff often seeks to take advantage of the treble damage provision of RICO.3 This article will analyze the application of the racketeering laws to com- mon, garden-variety commodities fraud cases. Specifically, this article addresses those cases where a brokerage firm is sued because of the illegal acts of its agents. It is the authors' contention that the treble damages pro- vision of RICO should not be applied to legitimate brokerage firms who are innocently involved in instances of commodities fraud through the acts of their agents. -

The Political Dynamics of Derivative Securities Regulation

The Political Dynamics of Derivative Securities Regulation Roberta Romanot The U.S. regulation of derivative securities--financial instruments whose value is derived from an underlying security or index of securities-is distinctive from that (~f other nations because it has multiple regulators for .financial derivatives and securities. Commentators have debated whether shifting to the unitary regulator approach taken by other nations would be more desirable and legislation to effect such a ~:hange has been repeatedly introduced in Congress. But it has not gotten very far. This article analyzes the political history of the regulation of derivative securities in the United States, in order to explain the institutional difference between the U.S. regime and other nations' and its staying power. It examines the j;JUr principal federal regulatory initiatives regarding derivative securities (the Future Trading Act of 1921, the Commodity Exchange Act of 1936, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission Act of 1974, and the Futures Trading Practices Act (if 1992), by a narrative account of the legislative process and a quantitative analysis (~f roll-call votes, committee-hearing witnesses, and issue salience. The multiple regulator status quo has persisted, despite dramatic changes in derivative markets, repeated efforts to alter it (by the securities industry in particular) and sh(fting political majorities, because of its support by the committee organization of Congress and by a tripartite winning coalition (if interest groups created by the 1974 legislation (farmers, futures exchanges, and banks). In what can best be ascribed to historical j;Jrtuity, different .financial market regulators are subject to the oversight (~f different congressional committees, and, consequently, the establishment (~f a unitary regulator would diminish the jurisdiction, and hence influence, ()f one (if the congressional committees. -

January 19,2006 Rule 10A-1

SIDLEY AUSTIN LLP BElJlNG GENEVA SAN FRANCISCO 787 SEVENTH AVENUE BRUSSELS HONG KONG SHANGHAI NEW YORK. NY 10018 CHICAGO LONDON SINGAPORE 2128395300 DALLAS LOS ANGELES fOKYO 212 839 5599 FAX NEW YORK WASHINGTON. DC I FOUNDED 1866 January 19,2006 Rule 10a-1; Rule 200(g) of Regulation SHO; Rule 10 1 and James A. Brigagliano, Esq. 102 of Regulation M; Section Assistant Director, Trading Practices ll(d)(l) and Rule lldl-2 ofthe Office of Trading Practices and Processing Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Division of Market Regulation Securities and Exchange Commission 100 F Street, N.E. Washington, DC 20549 Re: Request of DB Commodity Index Tracking Fund and DB Commodity Services LLC for Exemptive, Interpretative or No-Action Relief from Rule 10a-1 under, Rule 200(g) of Regulation SHO under, Rules 101 and 102 of Regulation M under, Section ll(d)(l) of and Rule lldl-2 under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended Dear Mr. Brigagliano: We are writing on behalf of DB Commodity Index Tracking Fund (the "Fund"), a ~elawkestatutory trust and a public commodity pool, and DB Commodity Services LLC ("DBCS"), which will be the registered commodity pool operator ("CPO) and managing owner (the "Managing Owner") of the Fund. The Fund and the Managing Owner (a) on their own behalf and (b) on behalf of (1) the DB Commodity Index Tracking Master Fund (the "Master Fund"); (2) ALPS Distributors, Inc. (the "Distributor"), which provides certain distribution-related administrative services for the Fund; (3) the American Stock Exchange ("'AMEX") and any -

IC 23-2-6 Chapter 6. Indiana Commodity Code IC 23-2-6-1

IC 23-2-6 Chapter 6. Indiana Commodity Code IC 23-2-6-1 "Board of trade" defined Sec. 1. As used in this chapter, "board of trade" refers to a person or group of persons engaged in: (1) buying or selling a commodity; or (2) receiving a commodity for sale on consignment; whether the person or group of persons is characterized as a board of trade, an exchange, or any other type of marketplace. As added by P.L.177-1991, SEC.10. IC 23-2-6-2 "Commissioner" defined Sec. 2. As used in this chapter, "commissioner" refers to the securities commissioner appointed under IC 23-19-6-1(a). As added by P.L.177-1991, SEC.10. Amended by P.L.27-2007, SEC.20. IC 23-2-6-3 "CFTC Rule" defined Sec. 3. As used in this chapter, "CFTC Rule" means a rule, regulation, or order of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission that is in effect on July 1, 1991, and any subsequent amendment, addition, or revision to the rule, regulation, or order unless the commissioner disallows the application to this chapter of the amendment, addition, or revision not later than ten (10) days after the effective date of the amendment, addition, or revision. As added by P.L.177-1991, SEC.10. IC 23-2-6-4 "Commodity" defined Sec. 4. As used in this chapter, "commodity" means, except as otherwise specified by a rule, regulation, or order of the commissioner, any of the following: (1) An agricultural, a grain, or a livestock product or byproduct. -

Corporate and Financial Weekly Digest)

June 4, 2010 SEC/CORPORATE SEC Chairman Issues Statement on GAAP-IFRS Convergence Project On June 2, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) announced modifications to their timetable for, and prioritization of, standards being developed by these boards in connection with improving U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and achieving convergence of GAAP and IFRS. According to the joint statement issued by the FASB and IASB, these boards had previously set June 2011 as the target date for completing all major convergence projects. During the past few months, stakeholders voiced concerns about their ability to provide input on the large number of exposure drafts of standards planned for publication in the second quarter of this year. In response, the FASB and IASB are developing a modified strategy to take account of these concerns that would prioritize certain major projects and stagger publication of exposure drafts, resulting in the extension of the target completion dates for some convergence projects to the second half of 2011. The Securities and Exchange Commission’s Chairman, Mary Schapiro, issued a statement on June 2 in which she indicated that the modification by the FASB and IASB to the timing for completion of certain convergence projects should not impact the SEC staff’s analyses under the Work Plan issued by the SEC in February 2010, the results of which will aid the SEC in its evaluation of the impact that the use of IFRS by U.S. issuers would have on the U.S. -

Comment Cftc V. Gibraltar Monetary Corp. and Vicarious Liability Under

COMMENT CFTC V. GIBRALTAR MONETARY CORP. AND VICARIOUS LIABILITY UNDER THE COMMODITY EXCHANGE ACT Jason E. Friedman* This Comment analyzes CFTC v. Gibraltar Monetary Corp., a 2009 decision in which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit introduced a control requirement into the Commodity Exchange Act’s vicarious liability provision. In so doing, the court rejected the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s long-held totality of the circumstances approach, in which any one factor, including control, is not dispositive of an agency relationship. This decision has created an undesirable situation in which retail foreign exchange dealers and futures commission merchants need not investigate the character of their introducing entities before retaining them, allowing them to easily avoid liability for frauds committed in furtherance of mutual profit. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 738 I. CLIMBING UP GIBRALTAR: COMMODITIES REGULATION, THE COMMODITY EXCHANGE ACT’S VICARIOUS LIABILITY PROVISION, AND CHEVRON DEFERENCE ........................................ 740 A. Overview of the Commodity Futures and Options Markets . 7 4 0 1. Commodities: More Than Just the Bacon in Your BLT ... 742 2. Commodities Derivatives Contracts: Futures, Forwards, and Options ....................................................................... 744 3. Categories of CFTC Registrants ........................................ 745 4. CFTC Enforcement Actions and -

Federal Regulation of Agricultural Trade Options

FEDERAL REGULATION OF AGRICULTURAL TRADE OPTIONS Michael S. Sackheim* I. Introduction .............................................................................................. 443 II. Regulation of Deferred Delivery Commodity Transactions .................... 445 III. Economic Characteristics of Commodity Options ................................... 446 IV. Regulation of Commodity Options .......................................................... 448 V. Pilot Program for Agricultural Trade Options ......................................... 451 A. Registration of Agricultural Trade Option Merchants ...................... 452 B. Disclosure .......................................................................................... 452 C. Financial Safeguards .......................................................................... 453 D. Recordkeeping and Reporting............................................................ 454 E. Physical Delivery Requirement ......................................................... 454 F. Persons Exempt from ATOM Registration ....................................... 457 VI. Conclusion ................................................................................................ 457 I. INTRODUCTION To manage the risks of fluctuations in commodity prices, various forms of hedging devices have been developed, including deliverable forward contracts, risk- shifting exchange-traded futures contracts and commodity options. Agricultural prices are often subject to greater volatility and uncertainty than prices -

INVESCO DB AGRICULTURE FUND (A Series of Invesco DB Multi-Sector Commodity Trust) (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2019 or ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-33238 INVESCO DB AGRICULTURE FUND (A Series of Invesco DB Multi-Sector Commodity Trust) (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 87-0778078 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) c/o Invesco Capital Management LLC 3500 Lacey Road, Suite 700 Downers Grove, Illinois 60515 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (800) 983-0903 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Units of Beneficial DBA NYSE Arca, Inc. Interest Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

![Federal Register]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9343/federal-register-2169343.webp)

Federal Register]

6351-01-P COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING COMMISSION 17 CFR Parts 1, 4, 41, and 190 RIN 3038-AE67 Bankruptcy Regulations AGENCY: Commodity Futures Trading Commission. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (the “Commission”) is amending its regulations governing bankruptcy proceedings of commodity brokers. The amendments are meant to comprehensively update those regulations to reflect current market practices and lessons learned from past commodity broker bankruptcies. DATES: Effective date: The effective date for this final rule is [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. The compliance date for § 1.43 is [INSERT DATE 1 YEAR AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER], for all letters of credit accepted, and customer agreements entered into, by a futures commission merchant prior to [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Robert B. Wasserman, Chief Counsel and Senior Advisor, 202-418-5092, [email protected], Ward P. Griffin, Senior Special Counsel, 202-418-5425, [email protected], Jocelyn Partridge, 202-418- 5926, [email protected], Abigail S. Knauff, 202-418-5123, [email protected], Division 1 of Clearing and Risk; Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Three Lafayette Centre, 1155 21st Street, NW, Washington, DC 20581. Table of Contents I. Background A. Background of the NPRM B. Major Themes in the Revisions to Part 190 II. Finalized Regulations A. Subpart A—General Provisions 1. Regulation 190.00: Statutory Authority, Organization, Core Concepts, Scope, and Construction 2. Regulation 190.01: Definitions 3. Regulation 190.02: General B. Subpart B—Futures Commission Merchant as Debtor 1. -

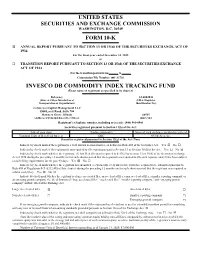

INVESCO DB COMMODITY INDEX TRACKING FUND (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2019 or ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-32726 INVESCO DB COMMODITY INDEX TRACKING FUND (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 32-6042243 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) c/o Invesco Capital Management LLC 3500 Lacey Road, Suite 700 Downers Grove, Illinois 60515 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (800) 983-0903 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Units of Beneficial Interest DBC NYSE Arca, Inc. Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Manipulation of Commodity Futures Prices-The Unprosecutable Crime

Manipulation of Commodity Futures Prices-The Unprosecutable Crime Jerry W. Markhamt The commodity futures market has been beset by large-scale market manipulations since its beginning. This article chronicles these manipulations to show that they threaten the economy and to demonstrate that all attempts to stop these manipulations have failed. Many commentators suggest that a redefinition of "manipulation" is the solution. Markham argues that enforcement of a redefined notion of manipulation would be inefficient and costly, and would ultimately be no more successful than earlierefforts. Instead, Markham arguesfor a more active Commodity Futures Trading Commission empowered not only to prohibit certain activities which, broadly construed, constitute manipulation, but also to adopt affirmative regulations which will help maintain a 'fair and orderly market." This more powerful Commission would require more resources than the current CFTC, but Markham argues that the additionalcost would be more than offset by the increasedefficiencies of reduced market manipulation. Introduction ......................................... 282 I. Historical Manipulation in the Commodity Futures Markets ..... 285 A. The Growth of Commodity Futures Trading and Its Role ..... 285 B. Early Manipulations .............................. 288 C. The FTC Study Reviews the Issue of Manipulation ......... 292 D. Early Legislation Fails to Prevent Manipulations .......... 298 II. The Commodity Exchange Act Proves to Be Ineffective in Dealing with M anipulation .................................. 313 A. The Commodity Exchange Authority Unsuccessfully Struggles with M anipulation ................................ 313 B. The 1968 Amendments Seek to Address the Manipulation Issue. 323 C. The 1968 Amendments Prove to be Ineffective ............ 328 tPartner, Rogers & Wells, Washington, D.C.; Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University Law Center; B.S. 1969, Western Kentucky University; J.D.