Changes in Airline Service Differ Significantly for Smaller Communities, but Limited Data on Ancillary Fees Hinders Further Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master Plan Update Chattanooga Metropolitan Airport

MASTER PLAN UPDATE CHATTANOOGA METROPOLITAN AIRPORT VOLUME 1 OF 2: Technical Report Prepared For CHATTANOOGA METROPOLITAN AIRPORT AUTHORITY Chattanooga, Tennessee July 2010 FINAL REPORT Chattanooga Metropolitan Airport Authority Master Plan Update TABLE OF CONTENTS (Volume 1 of 2) INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. i CHAPTER 1 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM ...................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Committees ....................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 Public Information Workshops ..........................................................................................1-1 1.4 Timing ............................................................................................................................... 1-2 1.5 Issues ................................................................................................................................ 1-2 1.6 Public Meetings of May 11, 2009 ......................................................................................1-3 1.6.1 User’s Group Comments on the Airport Development Concepts .............................. 1-3 1.6.2 The Technical Advisory Group Comments on the Airport Development Concepts ... 1-3 1.6.3 Public -

APR 2009 Stats Rpts

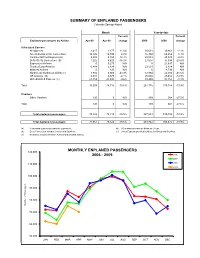

SUMMARY OF ENPLANED PASSENGERS Colorado Springs Airport Month Year-to-date Percent Percent Enplaned passengers by Airline Apr-09 Apr-08 change 2009 2008 change Scheduled Carriers Allegiant Air 2,417 2,177 11.0% 10,631 10,861 -2.1% American/American Connection 14,126 14,749 -4.2% 55,394 60,259 -8.1% Continental/Cont Express (a) 5,808 5,165 12.4% 22,544 23,049 -2.2% Delta /Delta Connection (b) 7,222 8,620 -16.2% 27,007 37,838 -28.6% ExpressJet Airlines 0 5,275 N/A 0 21,647 N/A Frontier/Lynx Aviation 6,888 2,874 N/A 23,531 2,874 N/A Midwest Airlines 0 120 N/A 0 4,793 N/A Northwest/ Northwest Airlink (c) 3,882 6,920 -43.9% 12,864 22,030 -41.6% US Airways (d) 6,301 6,570 -4.1% 25,665 29,462 -12.9% United/United Express (e) 23,359 25,845 -9.6% 89,499 97,355 -8.1% Total 70,003 78,315 -10.6% 267,135 310,168 -13.9% Charters Other Charters 120 0 N/A 409 564 -27.5% Total 120 0 N/A 409 564 -27.5% Total enplaned passengers 70,123 78,315 -10.5% 267,544 310,732 -13.9% Total deplaned passengers 71,061 79,522 -10.6% 263,922 306,475 -13.9% (a) Continental Express provided by ExpressJet. (d) US Airways provided by Mesa Air Group. (b) Delta Connection includes Comair and SkyWest . (e) United Express provided by Mesa Air Group and SkyWest. -

MAR 2009 Stats Rpts

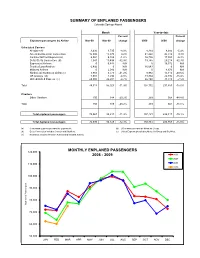

SUMMARY OF ENPLANED PASSENGERS Colorado Springs Airport Month Year-to-date Percent Percent Enplaned passengers by Airline Mar-09 Mar-08 change 2009 2008 change Scheduled Carriers Allegiant Air 3,436 3,735 -8.0% 8,214 8,684 -5.4% American/American Connection 15,900 15,873 0.2% 41,268 45,510 -9.3% Continental/Cont Express (a) 6,084 6,159 -1.2% 16,736 17,884 -6.4% Delta /Delta Connection (b) 7,041 10,498 -32.9% 19,785 29,218 -32.3% ExpressJet Airlines 0 6,444 N/A 0 16,372 N/A Frontier/Lynx Aviation 6,492 0 N/A 16,643 0 N/A Midwest Airlines 0 2,046 N/A 0 4,673 N/A Northwest/ Northwest Airlink (c) 3,983 6,773 -41.2% 8,982 15,110 -40.6% US Airways (d) 7,001 7,294 -4.0% 19,364 22,892 -15.4% United/United Express (e) 24,980 26,201 -4.7% 66,140 71,510 -7.5% Total 74,917 85,023 -11.9% 197,132 231,853 -15.0% Charters Other Charters 150 188 -20.2% 289 564 -48.8% Total 150 188 -20.2% 289 564 -48.8% Total enplaned passengers 75,067 85,211 -11.9% 197,421 232,417 -15.1% Total deplaned passengers 72,030 82,129 -12.3% 192,861 226,953 -15.0% (a) Continental Express provided by ExpressJet. (d) US Airways provided by Mesa Air Group. (b) Delta Connection includes Comair and SkyWest . (e) United Express provided by Mesa Air Group and SkyWest. -

REJECTED CONTRACTS Non-Debtor Party Contract

REJECTED CONTRACTS Non-Debtor Party Contract Description ACG 1030 Higgins LLC Office Lease Dated October 1, 2002 between Atlantic Coast Airlines and ACG 1030 Higgins LLC ACG 1030 Higgins LLC Rider 1 to Lease Agreement between Atlantic Coast Airlines and ACG 1030 Higgins LLC dated 1/15/2003 ACG 1030 Higgins LLC Rider 2 to Lease Agreement between Atlantic Coast Airlines and ACG 1030 Higgins LLC signed 10/1/2002 ACG 1030 Higgins, LLC Consent to Assignment among Atlantic Coast Airlines, ACG 1030 Higgins, LLC, and Air Wisconsin Airlines Corporation dated 12/1/2003 Aero Snow Removal a Division of East Coast Amendment I to Snow Removal Agreement between Atlantic Sweeping Inc Coast Airlines and Aero dated 11/1/2004 Snow Removal Agreement between Atlantic Coast Airlines, Inc. Aero Snow Removal, a division of East Coast dba United Express and Aero Snow Removal, a division of East Sweeping, Corp. Coast Sweeping, Corp. signed 11/19/1999 Airport Group International Agreement for Airport Services between Atlantic Coast Airlines dba Independence Air and Airport Group International dated 6/15/2004 Airport Group International Agreement for Into-Plane Fueling Services between Atlantic Coast Airlines dba Independence Air and Airport Group International Airline Use and Lease Agreement between Independence Air and Albany County Airport Authority Albany County Airport Authority dated 6/1/2004 Agreement Regarding Boarding Assistance between Atlantic Albany International Airport Coast Airlines and Albany International Airport Amadeus Global Travel Distribution, SA Amadeus AIS Agreement for Airlines between Independence Air, Inc. and Amadeus Global Travel Distribution, SA dated 2/1/2005 Amadeus Global Travel Distribution, SA Amadeus Instant Marketing Agreement between Independence Air, Inc. -

Annual Financial Report a Component Unit of the City of Knoxville, Tennessee for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2012

METROPOLITAN KNOXVILLE AIRPORT AUTHORITY 1937 – 2012 McGhee Tyson Airport P.O. Box 15600 Knoxville, TN 37901 2012 865/342-3000 • Fax865/342-3050 COMPREHENSIVE Email: [email protected] AnnuAl FinAnciAl REpoRt www.flyknoxville.com A component unit of the City of Knoxville, Tennessee for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2012 2012 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report A component unit of the City of Knoxville, Tennessee For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2012 PREPARED BY: Accounting and Finance Department of Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority www.flyknoxville.com 1 2 Introductory Section This section contains the following subsections: Table of Contents Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority Officials Letter of Transmittal and Exhibits Organizational Chart 3 4 METROPOLITAN KNOXVILLE AIRPORT AUTHORITY TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory section Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority Officials 7 Letter of transmittal and exhibits 9 Organizational chart 19 Financial section Report of Independent Auditors 23 Management’s discussion and analysis 25 Financial statements: Statements of net position 33 Statements of revenues, expenses and changes in net position 35 Statements of cash flows 36 Notes to financial statements 37 Statistical section (unaudited) Schedule 1: Operating revenues and expenses—last ten years 56 Schedule 2: Debt service coverage—last ten years 58 Schedule 3: Ratio of debt service and outstanding debt—last ten years 60 Schedule 4: McGhee Tyson Airport annual terminal rents and landing fees—last ten years 62 Schedule 5: Airline -

Journal of Air Transportation

University of Nebraska at Omaha Aviation Institute Journal of Air Transportation About the Journal Editorial Board Panel of Reviewers Volumes Submission Guidelines Author Index Order Form Sorenson Best Paper Award Journal of Air Transportation VOLUME 8, NUMBER 2--2003 University of Nebraska at Omaha 6001 Dodge Street ISSN: 1544-6980 Omaha, NE 68182 Library of Congress: HE9761.1.J68 (402) 554-3424 University of Nebraska at Omaha Aviation Institute About the Journal of Air Transportation THE JOURNAL Development The Journal of Air Transportation (JAT) mission is to provide the global community Scope immediate key resource information in all Dissemination areas of air transportation. Our goal is to be recognized as the preeminent scholarly Organizations journal in the aeronautical aspects of transportation. As an international and Editors interdisciplinary journal, the JAT provides a forum for peer-reviewed articles in all areas Personnel of aviation and space transportation research, policy, theory, case study, practice, and issues. While maintaining a broad scope, a key focal point of the journal is in the area of aviation administration and policy. ISSN: 1544-6980 Exit Library of Congress: HE9761.1.J68 Return University of Nebraska at Omaha Aviation Institute Development The JAT was conceptualized to fulfill an international void of scholarly publications in this area as identified by the primary organizers. It is envisioned that aviation leaders will utilize the JAT as a key decision-making tool. Scholarly rigor and standards will be uncompromised with regular evaluation by the Editorial Board and Panel of Reviewers. Return ISSN: 1544-6980 Exit Library of Congress: HE9761.1.J68 University of Nebraska at Omaha Aviation Institute Scope The JAT will accept manuscripts on all topics that relate to air transportation, both technical and non-technical. -

Budget-2020.Pdf

METROPOLITAN KNOXVILLE AIRPORT AUTHORITY McGHEE TYSON AIRPORT DOWNTOWN ISLAND AIRPORT FISCAL YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 2020 BUDGET METROPOLITAN KNOXVILLE AIRPORT AUTHORITY PASSENGER AIRLINE COST PER ENPLANEMENT FYE JUNE 30, 2020 BUDGET 6/30/2020 6/30/2019 6/30/2018 Estimated Enplanements 1,145,921 1,041,494 940,000 Passenger Airline Landing Fees $ 4,497,072 $ 4,218,705 $ 3,939,837 Airline Terminal Rental 3,006,584 2,726,736 2,632,753 Ramp Area Charges 1,058,123 911,064 784,053 Loading Bridge O & M 1,141,800 360,055 462,616 Total Passenger Airline Cost $ 9,703,579 $ 8,216,560 $ 7,819,259 Passenger Airline Cost per Enplanement $ 8.47 $ 7.89 $ 8.32 Budgeted Landing Fee $ 3.38 $ 3.40 $ 3.48 Budgeted Terminal Rates: Ticket Counter $ 47.65 $ 46.18 $ 44.52 Ticket Queuing 47.65 46.18 44.52 E-Ticket Kiosk 47.65 46.18 44.52 Ticket Office 47.65 46.18 44.52 Outbound Baggage 47.65 46.18 44.52 Operations Space 47.65 46.18 44.52 Baggage Service Office 47.65 46.18 44.52 Preferential Use Holdroom 47.65 46.18 44.52 Budgeted Ramp Fee $ 96,193 $ 91,106 $ 87,117 Budgeted Loading Bridge Fee $ 103,800 $ 40,006 $ 57,827 1 METROPOLITAN KNOXVILLE AIRPORT AUTHORITY McGHEE TYSON AIRPORT PROPOSED BUDGET COMPARISON PERCENTAGE FYE 6/2019 FYE 6/2020 INCREASE/ INCREASE/ CATEGORY BUDGET BUDGET (DECREASE) (DECREASE) OPERATING REVENUES: Landing Fees$ 5,141,749 $ 5,465,035 $ 323,286 6.29% Other Operating Revenue 27,839,992 31,221,996 3,382,004 12.15% TOTAL OPERATING REVENUE 32,981,741 36,687,031 3,705,290 11.23% OPERATING EXPENSES NOT INCLUDING DEBT SERVICE: Aviation Area Operating -

Saab 340 the VERSATILE TURBOPROP Saab 340 > the Versatile TURBOPROP

SAAB 340 THE VERSATILE TURBOPROP SAAB 340 > THE VERSATILE TURBOPROP 2 SAAB 340 > THE VERSATILE TURBOPROP ”WE ARE A NICHE MARKET operator...THE SAAB 340 IS A WORKHORSE AIRCRAFT AND very RELIABLE.” GEORG POMMER ROBIN HOOD Aviation CEO THE FLEXIBLE PERFORMER To safeguard against today’s rapidly changing environment and improve profitability, successful airlines must choose an aircraft that minimizes risk and is adaptable to an ever-changing market environment. In addition, passengers demand comfort and service similar to that offered by major carriers. The Saab 340 is a favorite among airline passengers due to its flexibility, comfort and reliable performance. With about half the operating costs of a regional jet, the Saab 340 can offer service in a variety of markets, large or small. RELIABILITY IN A VARIETY OF OPERATIONS The cost-effective Saab 340 consistently generates profits for a wide range of regional air transport services. With the right blend of technologies, the Saab 340 combines high productivity with dependability. THE “FACTS” @ 4Q – 2009 • 25-year track record • best selling 30-seat turboprop • more than 410 operational aircraft found on six continents and in 30 countries • over 13 million hours flown and an estimated 250 million passengers • consistent 99% dispatch reliability • award winning customer support services 3 SAAB 340 > THE VERSATILE TURBOPROP THE BIG AIRLINE CHOICE 4 SAAB 340 > THE VERSATILE TURBOPROP WORLD’S LARGEST 340BPLUS OPERATOR ”...OUR OVERALL OBJECTIVE IS TO PROVIDE A SEAMLESS The red, white and blue Delta livery is replacing Northwest colors service PRODUCT TO OUR on all aircraft and airport signage as the newly merged airline is passengers. -

Essays on Strategic Behavior in the U.S. Airline Industry

Essays on Strategic Behavior in the U.S. Airline Industry Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kerria Measkhan Tan, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Economics The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Matthew Lewis, Advisor James Peck Huanxing Yang c Copyright by Kerria Measkhan Tan 2012 Abstract In my first dissertation essay, \Incumbent Response to Entry by Low-Cost Carri- ers in the U.S. Airline Industry," I analyze the price response of incumbents to entry by low-cost carriers in the U.S. airline industry. Previous theoretical papers suggest that airlines might respond to entry by lowering prices to compete harder for existing customers or they might increase prices to exploit their brand-loyal customers. This paper tests which effect is more prominent in the airline industry. I find that when one of four low-cost carriers enters a particular route, legacy carrier incumbents respond differently than low-cost carrier incumbents to new low-cost carrier entry. Legacy carriers decrease their mean airfare, 10th percentile airfare, and 90th percentile air- fare before and after entry by a low-cost carrier. However, low-cost carriers do not significantly alter their pricing strategy. The differing incumbent responses can be attributed to the finding that low-cost carrier entrants tend to match the price set by rival low-cost carriers in the quarter of entry and tend to enter with a lower price than that of legacy carrier incumbents. The results also suggest that entry does not affect price dispersion by incumbent carriers. -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios -

Financial Statements

2013 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report A component unit of the City of Knoxville, Tennessee For the fiscal years ended June 30, 2013 and 2012 PREPARED BY: Accounting and Finance Department of Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority www.flyknoxville.com Introductory Section This section contains the following subsections: Table of Contents Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority Officials Letter of Transmittal and Exhibits Organizational Chart 1 METROPOLITAN KNOXVILLE AIRPORT AUTHORITY TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory section Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority Officials 3 Letter of transmittal and exhibits 4 Organizational chart 14 Financial section Report of Independent Auditors 16 Management’s discussion and analysis 19 Financial statements: Statements of net position 28 Statements of revenues, expenses and changes in net position 30 Statements of cash flows 31 Notes to financial statements 32 Statistical section (unaudited) Schedule 1: Operating revenues and expenses—last ten years 46 Schedule 2: Debt service coverage—last ten years 48 Schedule 3: Ratios of debt service and outstanding debt—last ten years 50 Schedule 4: McGhee Tyson Airport annual terminal rents and landing fees—last ten years 52 Schedule 5: Airline arrivals and departures—last ten calendar years 54 Schedule 6: Historical airline passenger activity—last ten calendar years 55 Schedule 7: Distribution of airline passengers—calendar year ended December 31, 2012 55 Schedule 8: Cargo—last ten calendar years 56 Schedule 9: Distribution of cargo—calendar year ended -

2014 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report

METROPOLITAN KNOXVILLE AIRPORT AUTHORITY 2014 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report A component unit of the City of Knoxville, Tennessee For the fiscal years ended June 30, 2014 and 2013 PREPARED BY: Accounting and Finance Department of Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority www.flyknoxville.com This page intentionally left blank Introductory Section This section contains the following subsections: Table of Contents Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority Officials Letter of Transmittal and Exhibits Organizational Chart 1 This page intentionally left blank 2 METROPOLITAN KNOXVILLE AIRPORT AUTHORITY TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory section Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority Officials 5 Letter of transmittal and exhibits 7 Organizational chart 16 Financial section Report of Independent Auditors 19 Management’s discussion and analysis 22 Financial statements: Statements of net position 32 Statements of revenues, expenses and changes in net position 34 Statements of cash flows 35 Notes to financial statements 37 Statistical section (unaudited) Schedule 1: Operating revenues and expenses—last ten years 52 Schedule 2: Debt service coverage—last ten years 54 Schedule 3: Ratios of debt service and outstanding debt—last ten years 56 Schedule 4: McGhee Tyson Airport annual terminal rents and landing fees—last ten years 58 Schedule 5: Airline arrivals and departures—last ten calendar years 60 Schedule 6: Historical airline passenger activity—last ten calendar years 61 Schedule 7: Distribution of airline passengers—calendar year ended December