Sebastian Christoffer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

York Aviation Contents

The Economic Impact of Arrivals Duty and Tax Free Shopping in the EU European Travel Retail Confederation September 2020 York Aviation Contents York Aviation Contacts Originated by: James Brass Partner Page T. +44 (0)7767 455614 E. [email protected] 1. Key Points 2 Matthew Jones Senior Consultant 1. Introduction 6 T. +44 (0)1625 614051 E. [email protected] 2. How would arrivals shops affect the market? 8 3. Estimating the economic impact of arrivals shops 10 4. Country Case Study: Spain 14 5. Country Case Study: Italy 20 6. Country Case Study: Germany 26 7. Potential Impact Across the EU 32 York Aviation is the trading name of York Aviation LLP, registered in Cardiff, No. 0C307526. Registered Office: Smithfield House, 92 North Street, Leeds, LS2 7PN Disclaimer of Liability Although every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the material and the integrity of the analysis presented herein, York Aviation LLP accepts no liability for any actions taken on the basis of its contents. York Aviation LLP is neither authorised nor regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority or the Prudential Regulation Authority. Anyone considering a specific investment should consult their own broker or other investment adviser. York Aviation LLP accepts no liability for any specific investment decision, which must be at the investor’s own risk. Copyright Copyright © 2020 York Aviation LLP. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part may be used or reproduced without permission. 1 York Aviation Key Points York Aviation Key Points The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on the European air transport industry and its partner sectors. -

Aena Magazine Rich.Indd 11 21/5/07 18:15:12 12 347332392383475498774709909029989935499

An official report for the aviation community. 3 Contents P.4 Javier Marin Director of Spanish airports Madrid Barajas A national asset P.8 José Manuel Hesse The ‘architect’ of Plan Barajas Award-winning P.27 Architectural design Maria Dolores Izquierdo P.33 P.11 Retail – every case is different Plan Barcelona The engine of Catalonia Innovation in IT P.38 P.17 First-rate, in-house expertise The Malaga plan A benchmark for tourist airports A three-way partnership P.20 Air navigation, airlines and airports The Levante Plan P.41 Alicante and Valencia Security P.24First, last and always Canarias plan P.47 The lucky airports P.51 4 Madrid Barajas Spain’s window on the world Airport Business asked Aena’s director of Spanish airports Javier Marin to spell out the significance of Plan Barajas, including the award-winning Madrid Barajas Terminal 4. John Frank-Keyes reports. “ 5 adrid Barajas is absolutely vital for air transport in Spain because of its hub function. However, we faced significant capacity limitations, so these infrastructure developments were crucial – and not just for Madrid, but for Spain and indeed for Europe. We now have the capacity to move up from being Europe’s fifth-ranked airport, and indeed it is something we have been able to achieve as we are now fourth in the first quarter of 2007,” Marin replied. Previously, Barajas had hourly runway capacity of 78 movements per hour with passenger mgrowth of about 8% a year. “The full benefits of the new capacity have really been felt with the advent of the winter season when we have been able to offer 90 movements per hour. -

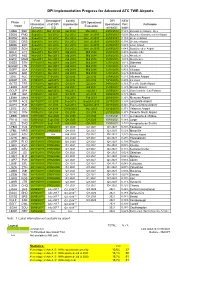

DPI Implementation Progress for Advanced ATC TWR Airports

DPI Implementation Progress for Advanced ATC TWR Airports First Developme Locally DPI NEW Phase | DPI Operational Information nt of DPI- Implemente Operational Perc Full name Airport Evaluation Exchange ICD d at NMOC traffic UKBB KBP Mar-2011 Mar 20122 Apr 2012 May 2012 29/05/2012 0,56% Boryspil Int Airport - Kiev EDDG FMO Sep-2012 Oct 2012 Dec 2012 Jan-Feb 2013 25/03/2013 0,09% Muenster Osnabrueck Int Airport EDDW BRE Sep-2012 Oct 2012 Dec 2012 Jan-Feb 2013 25/03/2013 0,15% Bremen Airport EDDC DRS Sep-2012 Oct 2012 Dec 2012 Jan-Feb 2013 25/03/2013 0,10% Dresden Airport EDDE ERF Sep-2012 Oct 2012 Dec 2012 Jan-Feb 2013 25/03/2013 0,02% Erfurt Airport EDDR SCN Sep-2012 Oct 2012 Dec 2012 Jan-Feb 2013 25/03/2013 0,04% SaarBruecken Airport EGLC LCY Nov-2013 Nov 2013 mid 2014 Mid 2014 05/05/2015 0,43% London City EGPD ABZ Nov-2013 Nov 2013 mid 2014 Mid 2014 05/05/2015 0,26% Aberdeen EGCC MAN Nov-2013 Nov 2013 mid 2014 Mid 2014 05/05/2015 1,03% Manchester EGSS STN 01/11/2013 Nov 2013 mid 2014 Mid 2014 17/07/2015 1,01% Stansted EGGW LTN 01/11/2013 Nov 2013 mid 2014 Mid 2014 17/07/2015 0,72% Luton EGPF GLA 01/11/2013 Nov 2013 mid 2014 Mid 2014 17/07/2015 0,43% Glasgow EGPH EDI 01/11/2013 Nov 2013 mid 2014 Mid 2014 17/07/2015 0,67% Edinburgh LEAL ALC 01/11/2015 Feb 2016 Q2 2016 Q2 2016 23/08/2016 0,51% Alicante Airport EGGP LPL 01/04/2015 april 2015 Jul 2016 Q3 2016 19/12/2016 0,20% Liverpool GCTS TFS 01/11/2015 april 2015 Q1 2017 Q2 2017 04/05/2017 0,35% Tenerife South Airport LEMG AGP 01/11/2015 april 2015 mid 2017 mid 2017 05/09/2017 0,72% Malaga -

LIST of REFERENCES ITW GSE 400 Hz Gpus AIRPORTS

Page 1 of 15 January 2017 LIST OF REFERENCES ITW GSE 400 Hz GPUs AIRPORTS Alger Airport Algeria 2005 Zvartnots Airport Armenia 2007 Brisbane Airport Australia 2013 Melbourne Airport Australia 2011-14 Perth Airport Australia 2011-12-13 Klagenfurt Airport Austria 1993 Vienna International Airport Austria 1995-2001-14-15 Bahrain International Airport Bahrain 2010-12 Minsk Airport Belarus 2014 Brussels International Airport Belgium 2001-02-08-15-16 Charleroi Airport Belgium 2006 Sofia Airport Bulgaria 2005 Air Burkina Burkina Faso 2004 Punta Arenas Chile 2001 Santiago Airport Chile 2011 Pointe Noitre Airport Congo Brazzaville 2009-10 Dubrovnik Airport Croatia 2014-16 La Habana Airport Cuba 2010 Larnaca Airport Cyprus 2008 Ostrava Airport Czech Republic 2010 Prague Airport Czech Republic 1996-97-2002-04-05-07-12-14-16 Aalborg Airport Denmark 1997-98-99-2012-15 Billund Airport Denmark 1999-2000-02-08-12-13-16 Copenhagen Airports Authorities Denmark 89-93-99-2000-01-03-07-09-10-11-12-13-14-15-16 Esbjerg Airport Denmark 2007-08-14 Hans Christian Andersen Airport (Odense) Denmark 1991-95-2015 Roenne Airport Denmark 1993 Karup Airport Denmark 1997-2016 Curacao Airport Dutch Antilles 2007 Cairo Intl. Airport Egypt 2015 Tallinn Airport Estonia 2004-05-14 Aéroport de Malabo Equatorial Guinea 2012 Vága Floghavn Faroe Islands 2015 Helsinki-Vantaa Airport Finland 1996-97-2000-05-06-09-10-13-14 Rovaniemi Airport Finland 2000 Turku Airport Finland 2014 Aéroport d’Aiglemont for Prince Aga Khan France 20007 Aéroport de Biarritz France 2009 Aéroport de Brest -

General Information

GENERAL INFORMATION Venue: Fundación Valenciaport, Sede Autoridad Portuaria de Valencia - Fase III, Avda. Muelle Turia s/n, 46024 Valencia (Spain). Transport: The airport is situated 8 km. west of the city, in the city limits of Manises. There are a frequent bus-service from the terminal to the city centre, metro line and taxi-service. METRO: There are two underground lines, which link the airport, the city centre and the port: the line 3 (Rafelbunyol- Aeroport) and the line 5 (Marítim Serrería - Torrent Av. / Aeroport). The station is at the ground floor of the regional flights terminal. The journey takes around 25 minutes. Tickets: €4.90 (3.90 + €1 for the card) To City centre: lines 3 or 5 - Xativa station. To Nord Railway Station: lines 3 or 5 - Xativa station. To Joaquin Sorolla Railway Station: lines 3 or 5 - A. Guimera station and line 1 - J. Sorolla station. To port: line 5 - Grau Canyamelar station. BUS: Aero-Bus Itinerary: Airport-Valencia-Airport. Direct service. Stops: Airport departures - Avenida del Cid (opposite to Local Police Office) - Calle Bailen - Calle Ángel Guimerá (next to Calle Juan Llorens) - Avenida del Cid - Airport departures. Timetable: From 6.00 to 22.00. Every 20 minutes. Price: 2.5 €. Line 150 Valencia-Airport Itinerary: Valencia - Mislata - Quart de Poblet - Manises – Airport Stops: Aeropuerto: Zona de Salidas Valencia: Paseo de la Pechina (Parque de Cabecera) - Avenida del Cid - Parque del Oeste - Obispo Amigó - Gran Via Ramón y Cajal (Cervantes) - Angel Guimerá 48. Mislata: Calle San Antonio 61, 104 - Hospital Militar Quart de Poblet: Avenida Reina de Valencia - Ayuntamiento de Mislata - Calle Trafalgar - Calle Villalba de Lugo. -

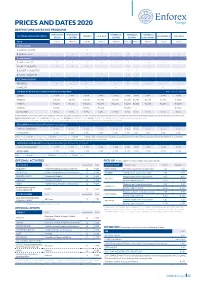

Prices and Dates 2020 Destinations, Dates and Programs

PRICES AND DATES 2020 DESTINATIONS, DATES AND PROGRAMS BARCELONA BARCELONA MARBELLA MARBELLA MARBELLA CULTURAL IMMERSION CAMPS MADRID MALAGA SALAMANCA VALENCIA BEACH CENTRO CENTRO ELVIRIA* LAS CHAPAS AGES 5 to 17 14 to 18 5 to 18 12 to 17 14 to 18 5 to 13 14 to 18 14 to 17 5 to 18 12 to 17 1-week session: A. JUNE 21 - JUNE 27 P P B. JUNE 28 - JULY 4 P P P P P P P P P 2-week session: C. JULY 5 - JULY 18 P P P P P P P P P D. JULY 19 - AUGUST 1 P P P P P P P P P E. AUGUST 2 - AUGUST 15 P P P P F. JULY 16 - AUGUST 29 P P P P P ACCOMMODATION RESIDENCE P P P P P P P P P P HOMESTAY P P P P P OVERNIGHT RESIDENCE CAMP OR HOMESTAY PROGRAM Prices are all-inclusive 1 WEEK € 995 € 995 € 995 € 895 € 995 € 795 € 795 € 795 € 795 € 895 2 WEEKS € 1,690 € 1,690 € 1,690 € 1,590 € 1,690 € 1,490 € 1,490 € 1,490 € 1,490 € 1,590 4 WEEKS € 3,190 € 3,190 € 3,190 € 2,890 € 3,190 € 2,690 € 2,690 € 2,690 € 2,690 € 2,890 6 WEEKS € 4,750 - € 4,750 € 4,290 - € 3,990 - - - € 4,290 EXTRA WEEK ** € 995 € 995 € 995 € 895 € 995 € 795 € 795 € 795 € 795 € 895 ALL-INCLUSIVE: 20 classes per week, accommodation, full board, activities, workshops, excursions, 4 meals/day (except in Marbella Centro and Valencia which include 3 meals/day), books, study materials, health insurance, sports, 24-hour supervision. -

Does Ryanair's Business Model Depend on Blackmail?

04/08/2011 Tirada: 579.249 Categoría: Inf General 4 Difusión: 444.300 Edición: English EL PAÍS, Thursday, August 4, 2011 Audiencia: 2.182.000 Página: 4 FEATURESAREA (cm2): 962,1 OCUPACIÓN: 89,2% V.PUB.: 28.974 BudgetNOTICIAS air travelEXCELTUR Does Ryanair’s business model depend on blackmail? The Irish airline is threatening to pull out of Spain’s provincial airports, saying they are unprofitable without further public money A. MARS / C. DELGADO / EL PAÍS year, after reaching a deal with Ryanair passengers in 2010 the Valencian regional govern- t a time when they ment that saw it receive must implement 643,432 ¤800,000, it began to increase drastic spending Santander flights. In the north of Spain, it A cuts, Spain’s regions 692,662 closed its operations in Foronda, face a tough choice. Santiago 4,615,164 just outside the Basque capital N/A Girona If they want to keep their provin- Lleida of Vitoria-Gasteiz, focusing on cial airports open, and keep the building up its presence in near- tourists and business travelers 740,750 by Santander, where it receives 198,612 370,485 Barcelona coming, they will have to contin- Valladolid official subsidies. Zaragoza 1,004,159 ue paying low-cost airlines and Reus Ryanair is also battling AENA regional carriers to do so. 4,801,246 on a number of fronts: in April it Ryanair has already an- Madrid 1,377,799 threatened to slash flights to Ali- nounced that from October it Valencia 1,611,191 cante by 80 percent this winter will no longer fly to Reus in Cata- Mallorca if AENA does not withdraw a lonia, cutting the airport’s traffic 626,585 ¤2-million increase in fees, Ibiza by half. -

Monthly OTP July 2019

Monthly OTP July 2019 ON-TIME PERFORMANCE AIRPORTS Contents On-Time is percentage of flights that depart or arrive within 15 minutes of schedule. Global OTP rankings are only assigned to all Airlines/Airports where OAG has status coverage for at least 80% of the scheduled flights. Regional Airlines Status coverage will only be based on actual gate times rather than estimated times. This may result in some airlines / airports being excluded from this report. If you would like to review your flight status feed with OAG please [email protected] MAKE SMARTER MOVES OAG Airport Monthly OTP – July 2019 Page 1 of 2 Home GLOBAL AIRPORTS – TOP 100 GLOBAL AIRPORT PERFORMANCE On-time performance GLOBAL AIRPORT PERFORMANCE On-time performance Airport Departures Rank No. flights Size Airport Departures Rank No. flights Size Panama City Tocumen Inter- ARH Arkhangelsk 97.3% 1 340 1,003 PTY 91.2% 51 5,966 149 national MSQ Minsk International Apt 96.7% 2 2,261 329 OKD Sapporo Okadama Apt 91.2% 52 419 926 SHJ Sharjah 96.3% 3 3,727 225 GFK Grand Forks 91.1% 53 180 1,173 LWY Lawas 95.9% 4 199 1,147 TKS Tokushima 90.8% 54 403 942 MKM Mukah 95.8% 5 177 1,181 HKD Hakodate 90.7% 55 765 684 OBO Obihiro 95.8% 6 310 1,025 NRN Duesseldorf Weeze Airport 90.6% 56 390 956 IWK Iwakuni 95.7% 7 186 1,161 KIJ Niigata 90.6% 57 889 620 GOJ Nizhny Novgorod 95.4% 8 549 819 SVX Yekaterinburg 90.5% 58 2,206 334 MWA Marion 95.1% 9 162 1,196 KKJ Kitakyushu 90.5% 59 1,046 548 SGC Surgut 95.1% 10 1,001 570 NKM Nagoya Komaki Airport 90.5% 60 744 699 UKB Osaka Kobe Airport 94.6% 11 -

Diners Club International Airport Lounge Pricelist April 11, 2019

Diners Club International Airport Lounge pricelist April 11, 2019 Diners Club Country City Airport Airport Lounge Member Fee Currency Guest Fee Currency Albania Tirana Tirana Nene Tereza International Airport Tirana Business Lounge 16.80 EUR 25 EUR Angola Luanda Quatro de Fevereiro Airport Pall Lounge 27 USD 30 USD Antiqua and Barbuda St John’s V.C. Bird International (ANU) Executive Lounge 33 USD 34 USD Argentina Buenos Aires Aeropuerto M. Pistarini Airport Star Alliance Lounge 36 USD 38 USD Armenia Yerevan Zvartnots International (EVN) Business Lounge 27 USD 29 USD Aruba Oranjestad Reina Beatrix International Airport AHI VIP Lounge (Gate 2) 27 USD 30 USD Oranjestad Reina Beatrix International Airport AHI VIP Lounge (Gate 8) 27 USD 29 USD Australia Adelaide International (ADL) REX LOUNGE 36 USD 36 USD Brisbane International (BNE) Plaza Premium Lounge 36 USD 37 USD Darwin International (DRW) Catalina Lounge 33 USD 34 USD Melbourne (MEL) PLAZA PREMIUM LOUNGE 36 USD 36 USD Melbourne (MEL) REX LOUNGE 36 USD 36 USD Sydney Sydney Kingsford Smith (SYD) REX LOUNGE 36 USD 36 USD Austria Graz Graz Airport VIP Lounge 19 EUR 25 EUR Innsbruck (INN) TYROL LOUNGE 25 EUR 26 EUR Salzburg (SZG) SALZBURG AIRPORT BUSINESS LOUNGE 31 EUR 31 EUR Vienna Wien-Schwechat Airport Air Lounge 20 EUR 20 EUR Vienna Wien-Schwechat Airport Jet Lounge 16,70 EUR 20 EUR Vienna Wien-Schwechat Airport Sky Lounge Non Schengen 16,70 EUR 20 EUR Vienna Wien-Schwechat Airport Sky Lounge Schengen 16,70 EUR 20 EUR Azerbaijan Baku Heydar Aliyev International (GYD) BAKU LOUNGE (Arrivals) 28 EUR 29 EUR Baku Heydar Aliyev International (GYD) MUGAM LOUNGE 28 EUR 29 EUR Baku Heydar Aliyev International (GYD) SALAM LOUNGE 28 EUR 29 EUR Khazar Heydar Aliyev International Airport Absheron Lounge 22 EUR 25 EUR Bahamas Marsh Harbour International (MHH) SKYVIEW AIRPORT LOUNGE 30 USD 31 USD Nassau Lynden Pindling International Airport Graycliff Divans 23. -

Airports and Airline Companies (Carriers) Coverage (Updated 080610)

Airports and airline companies (carriers) coverage (updated 080610) Traveas ambition is to have a complete coverage on a global travel market, and to have the best local coverage as possible on each market Traveas operates. At present, Traveas offers relevant and immediate coverage on the following airports and airline companies (carriers): Airport: Airline Company (carrier): (Airport code - ”Airport name”) (Airline code - ”Airline name”) AAL,"Aalborg Airport" 3K,"Jetstar Asia" AAR,"Tirstrup Airport" 6E,"IndiGo" ABZ,"Dyce Airport" 7H,"Era Aviation" ACE,"Lanzarote Airport" 9W,"Jet Airways (India)" AES,"Vigra Airport" AA,"American Airlines" AGP,"Malaga Airport" AC,"Air Canada" AKL,"Auckland International Airport" AF,"Air France" ALC,"Alicante Airport" AI,"Air India" ALF,"Alta Airport" AM,"Aeromexico" AMS,"Amsterdam-Schiphol Airport" AR,"Aerolineas Argentinas" ANR,"Deurne Airport" AS,"Alaska Airlines" ANX,"Andenes Airport" AT,"Royal Air Maroc" ARN,"Arlanda Airport" AY,"Finnair" ATH,"Eleftherios Venizelos International Airport" AZ,"Alitalia" AYT,"Antalya Airport" B6,"JetBlue Airways" BCN,"Barcelona Airport" BA,"British Airways" BDS,"Papola Casale Airport" BD,"bmi" BDU,"Bardufoss Airport" BW,"Caribbean Airlines" BEG,"Beograd Airport" C6,"Canjet Airlines" BEY,"Beirut International Airport" CA,"Air China International" BFS,"Belfast International Airport" CI,"China Airlines" BGO,"Flesland Airport" CM,"COPA" BGY,"Orio Al Serio Airport" CO,"Continental Airlines" BHD,"Belfast City Airport" CX,"Cathay Pacific Airways" BHX,"Birmingham International -

AIR TRANSPORT: QUARTERLY REPORT NO.12 3Rd QUARTER 2006 (July to September)

Annex 1: News AIR TRANSPORT: QUARTERLY REPORT NO.12 3rd QUARTER 2006 (July to September) A EU/REGULATORY ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 Commission approves public financing for six regional airports in Ireland.......................................................................... 2 High-level conference discusses future of aviation regulation ............................................................................................... 2 EU – African Union aviation seminar: meeting the needs of modern aviation...................................................................... 2 Commission approves changes to social aid for Martinique.................................................................................................. 2 EU and the Republic of Korea seal their agreement on GALILEO ........................................................................................ 2 Commission opens formal enquiry into restrictions to air services to Sardinia..................................................................... 2 Commission wants to strengthen the Single Market for Aviation ........................................................................................... 3 Cooperation agreement with the USA on modernising air traffic management..................................................................... 3 Proposed Regulation on common rules for air services in the EU........................................................................................ -

Asian Breeze (38)

Asian Breeze (38) (亜細亜の風) A Happy New Year to you all 24 February, 2015 Dear Coordinators and Facilitators in Asia/Pacific region. It may sound too late to say “A Happy New Year of 2015!”, but 19 February (Thursday) was a New Year 「新年」or “Spring Festival” 「春節」according to Chinese calendar. According to Chinese Zodiac, each year is symbolized with animals and this year 2015 is a “Goat/Sheep”. It is believed that people born under Goat/Sheep year (1943, 1955, 1967, 1979, 1991, 2003, 2015) is gentle mild-mannered, shy, stable, sympathetic, amicable, and brimming with a strong sense of kindheartedness and justice. By the way, are you born under Goat/Sheep zodiac? If so, is the above statement correctly representing your characteristics? For this issue, we have received a wonderful contribution from Mr. Ignacio Monasterio, Director of Coordination, AECFA (Asociación Española para la Coordinación y Facilitación de Franjas Horarias) in Spain. I hope you find it interesting. AECFA (Asociación Española para la Coordinación y Facilitación de Franjas Horarias) In Spain, the Public Business Entity Aena was appointed as the Slot Coordinator and Schedules Facilitator for the Spanish airports by the Ministry of Development and carried out this activity in the period 1993-2014 through its Slot Coordination Office. Since 15th September 2014, AECFA (Asociación Española para la Coordinación y Facilitación de Franjas Horarias) provides this service for the Spanish airports after being appointed as the Slot Coordinator and Schedules Facilitator by the Ministry of Development (Order FOM/1050/2014, of 17 June). AECFA is responsible for the slot coordination at 13 Spanish airports (Coordinated airports) and for the schedules facilitation in further 14 Spanish airports (Schedules Facilitated airports), according to the list of designated airports that is included in Royal Decree 20/2014, of 17 January.