Inquiry Into Tribal Self- Governance in Santal Parganas, Jharkhand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Length Research Article DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH

Available online at http://www.journalijdr.com International Journal of DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH ISSN: 2230-9926 International Journal of Development Research Vol. 06, Issue, 06, pp. 8009-8012, June, 2016 Full Length Research Article ADOPTION OF NEW TECHNOLOGIES OF HORTICULTURE TO FARMAR’S OF JAMTARA AND DUMKA DISTRICTS OF JHARKHAND PROVINCE IN INDIA *Jana, B.R. and Pan, R.S. ICAR-RCER, Research Centre of Ranchi, Namkum, Jharkhand, India-834010 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: To increase the livelihood security of the poor tribal farmer of Jamtara and Dumka ditricts the Received 19th March, 2016 horticulture technologies like, 1) Off season vegetable cultivation, 2) Year round vegetable Received in revised form production from 10 decimal area 3) One acre multi tier cropping were implemented and 4) 24th April, 2016 vertical cultivation of vine vegetables (pointed gourd) successfully introduced through NAIP Accepted 19th May, 2016 project launched by BAU, Ranchi and HARP, plandu as one of the consortium partner. The th Published online 30 June, 2016 maximum net income of Rs.24,950/- from filler crop (guava) intercrops (vegetables like potato, tomato, brinjal, radish, okra, chilli) was obtained by the farmer in the 5th year (2013) under fruit Key Words: based multi-tier cropping system established at farmars field, which generated employment of Technology, 181 man-days. Farmers earned the maximum net income of Rs.1571/- (Rs.3,92,750/ha) from Adoption rate, bottle gourd cultivation in 1.0 decimal (40 m2) area which generated employment of 11 man-days. Economics , The maximum annual net income of Rs.2544/- was obtained by the marginal farmer through Life style Improvement cultivation of summer kharif vegetables in 1.0 decimal. -

Dumka,Pin- 814101 7033293522 2 ASANBANI At+Po-Asa

Branch Br.Name Code Address Contact No. 1 Dumka Marwarichowk ,Po- dumka,Dist - Dumka,Pin- 814101 7033293522 2 ASANBANI At+Po-Asanbani,Dist-Dumka, Pin-816123 VIA 7033293514 3 MAHESHPUR At+Po-Maheshpur Raj, Dist-Pakur,Pin-816106 7070896401 4 JAMA At+Po-Jama,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814162 7033293527 5 SHIKARIPARA At+Po-Shikaripara,Dist-Dumka,Pin 816118 7033293540 6 HARIPUR At+Po-Haripur,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814118 7033293526 7 PAKURIA At+Po-Pakuria,Dist-Pakur,Pin816117 7070896402 8 RAMGARH At+Po-Ramgarh,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814102 7033293536 9 HIRANPUR At+Po-Hiranpur,Dist-Pakur,Pin-816104 7070896403 10 KOTALPOKHAR PO-KOTALPOKHR, VIA- SBJ,DIST-SBJ,PIN- 816105 7070896382 11 RAJABHITA At+Po-Hansdiha] Dist-Godda] Pin-814101 7033293556 12 SAROUNI At+Po-Sarouni] Dist-Godda] Pin-814156 7033293557 13 HANSDIHA At+Po-Hansdiha,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814101 7033293525 14 GHORMARA At+Po-Ghormara, Dist-Deoghar, Pin - 814120 7033293834 15 UDHWA At+Po-udhwa,Dist-Sahibganj pin-816108 7070896383 16 KHAGA At-Khaga,Po-sarsa,via-palajorihat,Pin-814146 7033293837 17 GANDHIGRAM At+Po-Gandhigram] Dist-Godda] Pin-814133 7033293558 18 PATHROLE At+po-pathrol,dist-deoghar,pin-815353 7033293830 19 FATHEPUR At+po-fatehpur,dist-Jamtara,pin-814166 7033293491 20 BALBADDA At+Po-Balbadda]Dist-Godda] Pin-813206 7033293559 21 BHAGAIYAMARI PO-SAKRIGALIGHAT,VIA-SBJ,PIN-816115 7070896384 22 MAHADEOGANJ PO-MAHADEVGANJ,VIA-SBJ,816109 7070896385 23 BANJHIBAZAR PO-SBJ AT JIRWABARI,816109 7070896386 24 DALAHI At-Dalahi,Po-Kendghata,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814101 7033293519 25 PANCHKATHIA PO-PANCHKATIA,VIA BERHATE,816102 -

On-The-Job Training

Health Response to Gender-Based Violence Competency Based Training Package for Blended Learning and On-the-Job-Training Facilitators’ Guide Government of Nepal Ministry of Health National Health Training Center 2016 Contributors List Mr. Achyut Lamichhane Former Director, National Health Training Center Mr. Anup Poudel International Organization for Migration Dr. Arun Raj Kunwar Kanti Children’s Hospital Ms. Beki Prasai United Nations Children’s Fund Ms. Bhawana Shrestha Dhulikhel Hospital Dr. Bimal Prasad Dhakal United Nations Population Fund Ms. Bindu Pokharel Gautam Suaahara, Save Ms. Chandra Rai Jhpiego Nepal Department of Forensic Medicine, Institute of Dr. Harihar Wasti Medicine Mr. Hem Raj Pandey Family Health Division Dr. Iswor Upadhyay National Health Training Center Ms. Jona Bhattarai Jhpiego Ms. Kamala Dahal Department of Women and Children SSP Krishna Prasad Gautam Nepal Police Dr. Kusum Thapa Jhpiego Mr. Madhusudan Amatya National Health Training Center Ms. Marte Solberg United Nations Population Fund Ms. Mina Bhandari Sunsari Hospital Dr. Mita Rana Tribhuwan University and Teaching Hospital Mr. Mukunda Sharam Population Division Ms. Myra Betron Jhpiego Mr. Parba Sapkota Population Division Dr. Rakshya Joshi Obstetrician and Gynecologist Nepal Health Sector Support Program/Ministry of Ms. Rekha Rana Health and Population Department of Forensic Medicine, Institute of Dr. Rijen Shrestha Medicine Mr. Robert J Lamburne UK Department for International Development Ms. Sabita Bhandari Lawyer Ms. Sandhya Limbu Jhpiego Dr. Saroja Pandey Paroparkar Maternity and Women’s Hospital Ms. Shakuntala Prajapati Management Division Ms. Suku Lama Paroparkar Maternity and Women’s Hospital Dr. Shilu Aryal Family Health Division Dr. Shilu Adhikari United Nations Population Fund National Health, Education, Information and Mr. -

Salient Highlights of Research / Others

13.1 : Salient highlights of Research 13.1.1 : GIS based Block level soil nutrient mapping Spatial variability in soil parameters including nutrients has been attributed to the parent material, topography, landforms, cropping pattern and fertilization history. Blanket nutrient recommendations further widen the variability and enhanced the risk of soil degradation in terms of soil organic carbon and nutrient depletion, acidity, green house gas emission, water and environmental pollution. Unfavorable economics on account of blanket recommendation are bound to adversely influence the enthusiasm of farmers to enhance investments in new technologies. This results in low farm productivity and poor soil health will jeopardize food security and agricultural sustainability. Soil nutrient mapping at district level was attempted in the past by collecting soil samples at the interval of two and half kilometer. The resultant map is being utilized for district planning. However, for translating the map information for farm planning soil sampling at closer interval (500 meter) is appropriate to capture all kind of variability in nutrient status. For bridging the outlined gaps NBSS & LUP, Nagpur and Regional Centre, Kolkata in collaboration with the Department of Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, BAU, Ranchi and Department of Agriculture & cane Development, Govt. of Jharkhand, has taken up a model project in Jharkhand state entitled “Assessment and Mapping of Some Important Soil Parameters including Macro & Micro Nutrients for Dumka, Jamtara and Hazaribagh districts for Optimum Land Use Plan”. The objective of the project is to prepare GIS aided block wise soil parameters maps including nutrients (Organic carbon, available N, P, K, S and available Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu, B and Mo) along with the maps of soil pH and surface texture block wise for Dumka, Jamtara and Hazaribagh districts of Jharkhand for helping in formulating optimum land use plan. -

The Adivasi Will Not Dance”

Postcolonial Text, Vol 12, No 1 (2017) Examining Subalterneity in Hansda Sowvendra Sekhar’s “The Adivasi Will Not Dance” Abin Chakraborty Chandernagore College, India In his discussion of Adivasi1 assertions in India, Daniel J. Rycroft remarks: In states such as Jharkhand (Koel-Karo dams), Madhya Pradesh (Forest rights), Orissa (Kashipur aluminium mining), Andhra Pradesh (Birla Periclase project) and Kerala (Wayanad wildlife sanctuary) etc., the coercion of the federal governments against those Adivasis protesting against the injustices of development exemplifies how Adivasis are frequently brutalised, criminalised and marginalised in the political, legal and economic discourses of the postcolonial nation... In India today, the routine abuse of land rights and cultural rights conferred to Adivasis leads to heightened claims for various forms of decentralised governance, as well as to the emergence of new forms of resistance, new dynamics of power between state and civil society, and new interpretations of subaltern pasts. (Rycroft 3-4) In this paper I read Hansda Sowvendra Sekhar’s short story set in the Pakur district of Jharkhand, “The Adivasi Will Not Dance,” in light of these evolving contexts of victimisation and resistance, while being mindful of the intersections of subaltern politics and the politics of the nation-state, the general absence of Adivasis from the domain of Indian English Literature, and the vexed question of representing subalterns. Adivasis and the History of Subjugation Considered to be the original inhabitants of India, who even preceded the Aryans, the Adivasis, a vast heterogeneous population dispersed across various regions of India, have been subjected to continuous exploitation since the establishment of British colonial rule. -

Jamtara District, Jharkhand

कᴂ द्रीय भूमि जल बो셍ड जल संसाधन, नदी विकास और गंगा संरक्षण विभाग, जल श啍ति िंत्रालय भारि सरकार Central Ground Water Board Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Ministry of Jal Shakti Government of India AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT OF GROUND WATER RESOURCES JAMTARA DISTRICT, JHARKHAND रा煍य एकक कायाडलय, रांची State Unit Office, Ranchi भारतसरकार Government of India जल शक्ति मंत्रालय Ministry of Jal Shakti जऱ संसाधन, नदी वर्वकास और गंगा संरक्षण वर्वभाग Department of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation केन्द्रीय भमम जऱ बो셍 ड ू Central Ground Water Board Aquifer Maps and Ground Water Management Plan of Jamtara district, Jharkhand( 2018-19) जऱभतृ न啍शे तथा भूजऱ प्रबंधन योजना जामताडा जजऱा,झारख赍셍 (2018-19) Principal Authors (Atul Beck, Assistant Hydrogeologist & Dr. Sudhanshu Shekhar, Scientist-D) रा煍य एकक कायाडऱय, रांची मध्य- ऩूर्वी क्षेत्र, ऩटना, 2020 State Unit Office, Ranchi Mid- Eastern Region, Patna, 2020 REPORT ON NATIONAL AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT PLAN OF JAMTARA DISTRICT, JHARKHAND 2018 – 19 (PART – I) CONTRIBUTORS’ Principal Authors Atul Beck : Assistant Hydrogeologist Dr.Sudhanshu Shekhar Scientist-D Supervision & Guidance A.K.Agrawal : Regional Director G. K. Roy Officer-In- Charge Hydrogeology, GIS maps and Management Plan Sunil Toppo : Junior Hydrogeologist DrAnukaran Kujur : Assistant Hydrogeologist Atul Beck : Assistant Hydrogeologist Hydrogeological Data Acquisition and Groundwater Exploration Sunil Toppo : Junior Hydrogeologist Dr Anukaran Kujur : Assistant Hydrogeologist Atul Beck : Assistant Hydrogeologist Geophysics B. K. Oraon : Scientist-D Chemical Analysis Suresh Kumar : Assistant (Chemist) i REPORT ON AQUIFER MAPS AND MANAGEMENT PLAN (PART – I) OF JAMTARA DISTRICT, JHARKHAND STATE (2018 - 19) Chapter Details Page No. -

Annual Report 2013-2014 New Final.Cdr

JHARKHAND VIKAS PARISHAD Registered Head Office: At+P.O.- Mandu, District- Rsmghar, Jhararkhand Extension office: At+P.O.- Amrapara, Landmark- Pokhariya Road, District-Pakur, Jharkhand - 814111 Visit us : www.jvpindia.org.in E-mail : [email protected] Only a life lived to others is a life worthwhile....... CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS E Aknowledgement ……………………………………………………………....... 1 We would like to thank the office bearers of all the Block and district members, Rural Local Bodies of the Panchayati Raj Institutions who took time out, provided the study team the information needed as well as their insights and valuable suggestions in this From the desk of Chairperson………………………………………………….. 3 E process of exploring ways of development. This study could not have proceeded without their support. AboutE Jharkhand Vikash Parisad.……………………………………………... 4 This study would also not have been completed without the support of staffs that are JVP Activities ………………………………………………………………….... 5 working very closely with community people, at the grass roots level, in the entire village, E panchayat selected for this study. We thank Mr. Anil Kr. Yadav (B.D.O), Mrs. Chitra Yadav (C.D.P.O), Mr,Parmesh Kushwaha (C.O),Dr. E. Ekka, Dr. Prem Kr. Marandi, Mrs. E Major activities and events Organized from April 2013-March 2014.……... 15 Sushila Murmu (B.O), Mr. Arun Kumar (D.S.C). We also wish to acknowledge the persistent work that has been put in by the rural E Photographs………………………..…………………………………………… 14 development Department. Media coverage………………………………………………………………... 18 Last, but definitely not the least, our heartfelt thanks to all the community people who not E only gave us time but also shared their experiences and personal information with us; and to whom we would like to dedicate this report with a hope of being able to translate it into real actions for them. -

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Inner Frontiers; Santal Responses to Acculturation

Inner Frontiers: Santal Responses to Acculturation Marne Carn- Bouez R 1991: 6 Report Chr. Michelsen Institute Department of Social Science and Development ISSN 0803-0030 Inner Frontiers: Santal Responses to Acculturation Marne Carn- Bouez R 1991: 6 Bergen, December 1991 · CHR. MICHELSEN INSTITUTE Department of Social Science and Development ReporF1991: 6 Inner Frontiers: Santal Responses to Acculturation Marine Carrin-Bouez Bergen, December 1991. 82 p. Summary: The Santals who constitute one of the largest communities in India belong to the Austro- Asiatie linguistic group. They have managed to keep their language and their traditional system of values as well. Nevertheless, their attempt to forge a new identity has been expressed by developing new attitudes towards medicine, politics and religion. In the four aricles collected in this essay, deal with the relationship of the Santals to some other trbal communities and the surrounding Hindu society. Sammendrag: Santalene som utgjør en av de tallmessig største stammefolkene i India, tilhører den austro- asiatiske språkgrppen. De har klar å beholde sitt språk og likeså mye av sine tradisjonelle verdisystemer. Ikke desto mindre, har de også forsøkt å utvikle en ny identitet. Dette blir uttrkt gjennom nye ideer og holdninger til medisin, politikk og religion. I de fire artiklene i dette essayet, blir ulike aspekter ved santalene sitt forhold til andre stammesamfunn og det omliggende hindu samfunnet behandlet. Indexing terms: Stikkord: Medicine Medisin Santal Santal Politics Politik Religion -

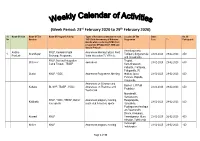

Week Period: 23Rd February 2020 to 29Th February 2020

rd th (Week Period: 23 February 2020 to 29 February 2020) Sl. Name Of State Name Of The Name Of Program/ Activity Types of Activities undertaken to mark Location Of The Dates No. Of No Kendras 150th Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Programme From To Participants . Gandhi while conducting NYKS Core programme NPYAD, NYLP, SBM and Special Projects Ananthapuramu Andhra NYLP, Kashmiri Youth Awareness Meetng Cultural Field 1. Ananthapur Tadipatri, Singanamala 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 450 Pradesh Exchange Programme Visits Interaction To VIPs etc. and Uravakonda NYLP, National Integration Tirupati, Chittooor awareness 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 600 Camp Tirupati, TBAEP Karvetinagaram Pallaptla, Prattipadu, Piduguralla, 75 Guntur NYLP, YCDC Awareness Programme, Meeting thalluru, ipuru, 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 600 Ponnuru, Bapatla, Vinukonda Awareness on Schemes and Badvel L R Palli Kadapa BL NYP, TBAEP , YCDC Awareness on Themmes and 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 650 Proddatur Youth Club Maredemilli, Sankavaram, NYLP, YCDC, TBEAP, District Awareness program, meeting, Rangempetta, Kakinada 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 600 level sports youth club formation, sports Samalkota, Peddapuram,Amalapur am,Rajamundry Dhone, Kodumuru, Kurnool NYLP Yemmigannur, Aluru, 23-02-2020 26-02-2020 400 Atmakur, Pathikonda Venkatagiri Nellore NYLP Awareness program, meeting 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 160 Indukurpeta Page 1 of 37 Sl. Name Of State Name Of The Name Of Program/ Activity Types of Activities undertaken to mark Location Of The Dates No. Of No Kendras 150th Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Programme From To Participants . Gandhi while conducting NYKS Core programme NPYAD, NYLP, SBM and Special Projects District Folk & Cultural Folk Cultural Programme Gudur 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 200 Maddipadu, Ulvapadu, Markapur, Ongole TBEAP, Dist Folk Cultural, Awareness meeting, Folk Santhanuthulapadu, 23-02-20 29-02-20 546 (Prakasam) YC DC,NYLP Cultural prog. -

District Profile DUMKA

District Profile DUMKA 1 | Page Index S. No. Topic Page No 1 About District 3 2 Road Accident 4 2.a Accidents According to the Classification of Road 4 2.b Accidents According to Classification of Road Features 5 2.c Accidents According to Classification of Road Environment 5 2.d Accidents Classification According to Urban/Rural & Time 6 2.e Accidents Classification According to Weather Conditions 7 3 Urgent Need of Stiff Enforcement drive 7 4 Need of Road Safety 7 4.a Glimpse of Awareness Program/workshop in School & Colleges 8 4.b Glimpse of Painting, Quiz & GD Competition in School & Colleges 9 4.c Prize distribution 10 4.d Glimpse of Road Safety Awareness Activities 11 4.e Hoardings at different locations of block, P.S & C.S.C. 12 5 Measures taken by NH/SH/RCD divisions for Road Safety 13 5.a Glimpse of Measures taken by NH/SH/RCD divisions for Road Safety 15 5.b Black Spot Inspection 15 6 Enforcement Drive by DTO & Police 15 7 Accident Spot Inspection/ Mobi-Tab Fillup on spot 15 8 To save lives during “Golden Hour” 16 9 Hit & Run 17 10 CHALLENGES WE (DPIU) ARE FACING 17 2 | Page About District Dumka is the headquarters of Dumka district and Santhal Pargana region, it is a city in the state and also sub capital of Jharkhand. Area: 3,761 Sq. Km. Population: 13,21,442 Language: Hindi,Santhali, Bangla Villages: 2925 Male: 6,68,514 Female: 6,52,928 There are three state boundaries i.e.