The Adivasi Will Not Dance”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2013-2014 New Final.Cdr

JHARKHAND VIKAS PARISHAD Registered Head Office: At+P.O.- Mandu, District- Rsmghar, Jhararkhand Extension office: At+P.O.- Amrapara, Landmark- Pokhariya Road, District-Pakur, Jharkhand - 814111 Visit us : www.jvpindia.org.in E-mail : [email protected] Only a life lived to others is a life worthwhile....... CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS E Aknowledgement ……………………………………………………………....... 1 We would like to thank the office bearers of all the Block and district members, Rural Local Bodies of the Panchayati Raj Institutions who took time out, provided the study team the information needed as well as their insights and valuable suggestions in this From the desk of Chairperson………………………………………………….. 3 E process of exploring ways of development. This study could not have proceeded without their support. AboutE Jharkhand Vikash Parisad.……………………………………………... 4 This study would also not have been completed without the support of staffs that are JVP Activities ………………………………………………………………….... 5 working very closely with community people, at the grass roots level, in the entire village, E panchayat selected for this study. We thank Mr. Anil Kr. Yadav (B.D.O), Mrs. Chitra Yadav (C.D.P.O), Mr,Parmesh Kushwaha (C.O),Dr. E. Ekka, Dr. Prem Kr. Marandi, Mrs. E Major activities and events Organized from April 2013-March 2014.……... 15 Sushila Murmu (B.O), Mr. Arun Kumar (D.S.C). We also wish to acknowledge the persistent work that has been put in by the rural E Photographs………………………..…………………………………………… 14 development Department. Media coverage………………………………………………………………... 18 Last, but definitely not the least, our heartfelt thanks to all the community people who not E only gave us time but also shared their experiences and personal information with us; and to whom we would like to dedicate this report with a hope of being able to translate it into real actions for them. -

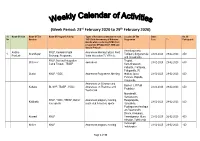

Week Period: 23Rd February 2020 to 29Th February 2020

rd th (Week Period: 23 February 2020 to 29 February 2020) Sl. Name Of State Name Of The Name Of Program/ Activity Types of Activities undertaken to mark Location Of The Dates No. Of No Kendras 150th Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Programme From To Participants . Gandhi while conducting NYKS Core programme NPYAD, NYLP, SBM and Special Projects Ananthapuramu Andhra NYLP, Kashmiri Youth Awareness Meetng Cultural Field 1. Ananthapur Tadipatri, Singanamala 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 450 Pradesh Exchange Programme Visits Interaction To VIPs etc. and Uravakonda NYLP, National Integration Tirupati, Chittooor awareness 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 600 Camp Tirupati, TBAEP Karvetinagaram Pallaptla, Prattipadu, Piduguralla, 75 Guntur NYLP, YCDC Awareness Programme, Meeting thalluru, ipuru, 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 600 Ponnuru, Bapatla, Vinukonda Awareness on Schemes and Badvel L R Palli Kadapa BL NYP, TBAEP , YCDC Awareness on Themmes and 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 650 Proddatur Youth Club Maredemilli, Sankavaram, NYLP, YCDC, TBEAP, District Awareness program, meeting, Rangempetta, Kakinada 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 600 level sports youth club formation, sports Samalkota, Peddapuram,Amalapur am,Rajamundry Dhone, Kodumuru, Kurnool NYLP Yemmigannur, Aluru, 23-02-2020 26-02-2020 400 Atmakur, Pathikonda Venkatagiri Nellore NYLP Awareness program, meeting 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 160 Indukurpeta Page 1 of 37 Sl. Name Of State Name Of The Name Of Program/ Activity Types of Activities undertaken to mark Location Of The Dates No. Of No Kendras 150th Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Programme From To Participants . Gandhi while conducting NYKS Core programme NPYAD, NYLP, SBM and Special Projects District Folk & Cultural Folk Cultural Programme Gudur 23-02-2020 29-02-2020 200 Maddipadu, Ulvapadu, Markapur, Ongole TBEAP, Dist Folk Cultural, Awareness meeting, Folk Santhanuthulapadu, 23-02-20 29-02-20 546 (Prakasam) YC DC,NYLP Cultural prog. -

E-Procurement Notice

e-Procurement Cell JHARKHAND STATE BUILDING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION LTD., RANCHI e-Procurement Notice Sr. Tender Work Name Amount in (Rs) Cost of Bids Completio No Reference BOQ (Rs) Security(Rs) n Time . No. Construction of 1 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Kunda Block of Chatra District of 1 3,16,93,052.00 10,000.00 6,33,900.00 15 months 0/2016-17 North Chotanagpur Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 1 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Tundi Block of Dhanbad District of 2 3,16,93,052.00 10,000.00 6,33,900.00 15 months 1/2016-17 North Chotanagpur Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 2 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Bagodar and Birni Block of Giridih 3 6,33,85,987.00 10,000.00 12,67,800.00 15 months 2/2016-17 District of North Chotanagpur Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 2 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Jainagar and Koderma Block of 4 6,33,85,987.00 10,000.00 12,67,800.00 15 months 3/2016-17 Koderma District of North Chotanagpur Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 2 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Boarijor and Sunder Pahari Block 5 6,33,85,987.00 10,000.00 12,67,800.00 15 months 4/2016-17 of Godda District of Santhal Pargana Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 1 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Amrapara Block of Pakur District 6 3,16,93,052.00 10,000.00 6,33,900.00 15 months 5/2016-17 of Santhal Pargana Division of Jharkhand. -

Office of the Sub- Divisional Officer, Pakur Order (Viii) West- Jojo Tola

,27 Office of the Sub- divisional Officer, Pakur (Confidential Section) Order Government of Jharkhand, Department of Home, Prison and Disaster Management (Disaster Management Department) has issued various measures for strict compliance for containment of COVID- 19 Epidemic vide letter No. 248, dated 30.03.2020. In Pakur District 2 and several others in the surroundings, COVID-19 positive case has been detected in the Village- Paderkola, Block- Amrapara , P,S- Amrapara, District- Pakur, which requires detailed measures for active contact tracing. To facilitate this, it is necessary to make the area as a micro containment zone and to restrict public from entering into and going out of the micro Containment Zone. Now therefore in larger public interest and with a view to contain the spread of COVID-19. I, under signatory hereby direct to implement the following directions:- A. The following ard4 are indicated as micro Containment Zone boundary: (v) North- House of lotin Maraiya (Kairatola) (ri) South- House of Manik Murmu (vii) East- House of.Gopal Tudu (viii) West- Jojo Tola B. There will be Buff(i zone at all sides in the radius of 500 Meter of the micro Containment Zone. C. And whereas mentioned lvith clause 3 of MHA order, dated 01-05-2020 in the Containment Zone, following activities shall be undertaken by the Incident Commandbr -curn- Block Development Officer, Amrapara with the help of special cel1s constituted for the purpose mentioned below. (i) Contact tracing to be done by special Cell under the leadership of Sri Pramod Kumar Das, Executive Magistrate' Pakur, SDPO, Maheshpur and B.D.O. -

Inquiry Into Tribal Self- Governance in Santal Parganas, Jharkhand

INQUIRY INTO TRIBAL SELF- GOVERNANCE IN SANTAL PARGANAS, JHARKHAND By Hasrat Arjjumend INQUIRY INTO TRIBAL SELF-GOVERNANCE IN SANTAL PARGANAS, JHARKHAND by Hasrat Arjjumend Railway Reservation Building 134, Street 17, Zakir Nagar, Okhla Opp. New Friends Colony A-Block New Delhi – 110 025 India Tel: 011-26935452, 9868466401 Fax: +91-11-26936366 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Web: www.grassrootsglobal.net/git © Hasrat Arjjumend, 2005 PREFACE Period of half a decade in looking closely at the PRIs in the Scheduled Areas of undivided Madhya Pradesh was not less for me to guesstimate the prevalence and interference of bureaucracy and officialdom, and its associated callousness, domination, insensitivity, etc., in the lives of tribes and poor. Nothing significant has ever changed in the tribal villages except that of penetration of party politics, growing de-fragmentation in the families/communities, heavy inflow of funds with least visible impacts, and increasing number of NGOs claiming empowering the gram sabhas. Question now arises, are the tribes the animals for our unprecedented experimentation, or do we respect them as equal human beings deserving to ‘determine themselves’ to rule, to govern their lives and resources? Public institutions, more often unaccountable, of the ‘mainstream’ seem to have dearth of willingness on the later question. Where do we want to land then? Tribal self-rule first and foremost is a peculiar area to understand, to work in. I so far have encountered the civil society actors -

INDEPENDENT ASSESSMENT of KALA-AZAR ELIMINATION PROGRAMME INDIA 9-20 December 2019, India

INDEPENDENT ASSESSMENT OF KALA-AZAR ELIMINATION PROGRAMME INDIA 9-20 December 2019, India INDEPENDENT ASSESSMENT OF KALA-AZAR ELIMINATION PROGRAMME INDIA 9-20 December 2019, India Title: INDEPENDENT ASSESSMENT OF KALA-AZAR ELIMINATION PROGRAMME INDIA ISBN: 978-92-9022-796-0 © World Health Organization [2020] Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. [Title]. [New Delhi]: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia; [2020]. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. -

Environmental Assessment

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report (Scheme T, Volume 1) Public Disclosure Authorized Jharkhand Urja Sancharan Final Report Nigam Limited January 2018 www.erm.com The Business of Sustainability FINAL REPORT Jharkhand Urja Sancharan Nigam Limited Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report (Scheme T, Volume 1) 31 January 2018 Reference # 0402882 Reviewed by: Avijit Ghosh Principal Consultant Approved by: Debanjan Bandyapodhyay Partner This report has been prepared by ERM India Private Limited a member of Environmental Resources Management Group of companies, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. TABLE OF CONTANT EXECUTIVE SUMMERY I 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 PROJECT OVERVIEW 1 1.3 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THIS ESIA 2 1.4 STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT 2 1.5 LIMITATION 3 1.6 USES OF THIS REPORT 3 2 POLICY, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAME WORK 5 2.1 APPLICABLE LAWS AND STANDARDS 5 2.2 WORLD BANK SAFEGUARD POLICY -

Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report (Scheme T, Volume 2)

Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report (Scheme T, Volume 2) Jharkhand Urja Sancharan Final Report Nigam Limited January 2018 www.erm.com The Business of Sustainability FINAL REPORT Jharkhand Urja Sancharan Nigam Limited Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report (Scheme T, Volume 2) 31 January 2018 Reference # 0402882 Reviewed by: Avijit Ghosh Principal Consultant Approved by: Debanjan Bandyapodhyay Partner This report has been prepared by ERM India Private Limited a member of Environmental Resources Management Group of companies, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I 1 INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 BACKGROUND 7 1.2 PROJECT OVERVIEW 7 1.3 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THIS ESIA 8 1.4 STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT 8 1.5 LIMITATION 9 1.6 USES OF THIS REPORT 9 2 POLICY, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAME WORK 11 2.1 APPLICABLE LAWS AND STANDARDS 11 2.2 WORLD BANK SAFEGUARD POLICY 15 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 17 3.1 PROJECT LOCATION 17 3.2 ACCESSIBILITY 17 3.3 TRANSMISSION LINES PROJECT PHASES AND -

List of Safe, Semi-Critical,Critical,Saline And

Categorisation of Assessment Units State / UT District Name of Assessment Assessment Unit Category Area Type District / Unit Name GWRE Andaman & Nicobar Bampooka Island Bampooka Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Car Nicobar Island Car Nicobar Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Chowra Island Chowra Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Great Nicobar Island Great Nicobar Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Kamorta Island Kamorta Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Katchal Island Katchal Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Kondul Island Kondul Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Little Nicobar Island Little Nicobar Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Nancowrie Island Nancowrie Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Pilomilo Island Pilomilo Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Teressa Island Teressa Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Tillang-chang Island Tillang-chang Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Trinket Island Trinket Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & North & Aves Island Aves Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Middle Andaman & North & Bartang Island Bartang Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Middle Andaman & North & East Island East Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Middle Andaman & North & Interview Island Interview Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Middle Andaman & North & Long Island Long Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Middle Andaman & North & Middle -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report (Scheme T, Volume 1) Public Disclosure Authorized Jharkhand Urja Sancharan Final Report Nigam Limited January 2018 www.erm.com The Business of Sustainability FINAL REPORT Jharkhand Urja Sancharan Nigam Limited Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report (Scheme T, Volume 1) 31 January 2018 Reference # 0402882 Reviewed by: Avijit Ghosh Principal Consultant Approved by: Debanjan Bandyapodhyay Partner This report has been prepared by ERM India Private Limited a member of Environmental Resources Management Group of companies, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. TABLE OF CONTANT EXECUTIVE SUMMERY I 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 PROJECT OVERVIEW 1 1.3 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THIS ESIA 2 1.4 STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT 2 1.5 LIMITATION 3 1.6 USES OF THIS REPORT 3 2 POLICY, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAME WORK 5 2.1 APPLICABLE LAWS AND STANDARDS 5 2.2 WORLD BANK SAFEGUARD POLICY -

Migration of Santal Labourers from Jharkhand: a Case Study

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 12, Ver. 2 (December. 2018) 09-13 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Migration of Santal Labourers from Jharkhand: A Case Study Damian Tudu1, Dr. K. A. Michael2 1 Research Scholar, Department of Economics, St. Joseph’s College, Tiruchirappalli, India 2 Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, St. Joseph’s College, Tiruchirappalli, India Corresponding Author: Damian Tudu Abstract: Labour out- migration among the Santal labourers has been taking place since pre independence period. The Santal tribals lived in the district of Santal Parganas which was a part of Bihar then, which got separated in 2001 and now in Jharkhand. Since the emergence of Jharkhand more than 15 years have passed but economic condition among the Santal tribe has hardly improved. The region is gripped under poverty, illiteracy and under development, which mars the picture from every human development index. This grim situation compels the Santal tribals and other tribal labourers to migrate to other destinations for employment and survival. The present paper is a deeper study about the migration among the Santal tribe. The paper aims to know the causes of migration, impact of migration and also to know the difficulties faced by the Santal migrant labourers. Keywords: Migration, Santal tribe, labourers, unemployment. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 27-11-2018 Date of acceptance: 08-12-2018 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION Migration is a part of human history; nevertheless, the 19th and 20th centuries witnessed population movement on an unprecedented scale [1]. In developing countries like India migration takes place due to push factors like poverty, unemployment, natural calamities and underdevelopment at the place of origin [2]. -

![Kj[K.M F”K{Kk Ifj;Kstuk] Ikdqm+A ¼Lexz F”K{Kk Vfhk;Ku½ Vfrvyidkyhu Fufonk Vkea=.K Lwpuk La[;K % 01@2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9495/kj-k-m-f-k-kk-ifj-kstuk-ikdqm-a-%C2%BClexz-f-k-kk-vfhk-ku%C2%BD-vfrvyidkyhu-fufonk-vkea-k-lwpuk-la-k-01-2019-6859495.webp)

Kj[K.M F”K{Kk Ifj;Kstuk] Ikdqm+A ¼Lexz F”K{Kk Vfhk;Ku½ Vfrvyidkyhu Fufonk Vkea=.K Lwpuk La[;K % 01@2019

>kj[k.M f”k{kk ifj;kstuk] ikdqM+A ¼lexz f”k{kk vfHk;ku½ vfrvYidkyhu fufonk vkea=.k lwpuk la[;k % 01@2019 1. foKkiunkrk dk uke ,oa irk % ftyk f”k{kk inkf/kdkjh] ikdqM+ 2- ifjek.k foi= dh fcØh dh frfFk ,oa irk % d½ fnukad 08-07-2019] dks iwokZg~u 10%30 ls 05%30 rd [k½ irk % lexz f”k{kk vfHk;ku] >kj[k.M f”k{kk ifj;kstuk] ikdqM+ eq[; Mkd?kj] ikdqM+ ds lehi] ftyk& ikdqM] fiu& 816107 3- fufonk izkfIr dh frfFk ,oa irk % d½ fnukad % 10-07-2019] vijkg~u 03%00 rd] [k½ irk % Øe 2 ¼[k½ ds vuqlkj 4- fufonk [kksyus dh frfFk ,oa irk % d½ fnukad % 10-07-2019] vijkg~u 03%30 cts] [k½ irk % Øe 2¼[k½ ds vuqlkj 5- ;kstuk en % vkdka{kh ftyk f”k{kk iz{ks= ;kstuk en 6- dk;Z fooj.kh % & Ø- izkDdfyr vxz/ku dh ifjek.k dk;Z la- dk;Z dk uke jkf”k ¼:0½ jkf”k foi= dk lekfIr dh ¼:0½ ewY; ¼:0½ vof/k Development of 12 Smart Classroom in Pakur Block of Pakur 1 District under Aspirational District Programme 14,56,800.00 29200 2000 15 fnu Development of 07 Smart Classroom in Hiranpur Block of 2 Pakur District under Aspirational District Programme 8,49,800.00 17000 2000 15 fnu Development of 10 Smart Classroom in Littipara Block of Pakur 12,14000.00 24500 2000 3 District under Aspirational District Programme 15 fnu Development of 07 Smart Classroom in Amrapara Block of 8,49,800.00 17000 2000 4 Pakur District under Aspirational District Programme 15 fnu Development of 15 Smart Classroom in Maheshpur Block of 18,21,000.00 36500 2000 5 Pakur District under Aspirational District Programme 15 fnu Development of 08 Smart Classroom in Pakuria Block of Pakur 9,71,200.00 19500 2000