ZHANG YIMOU's RED SORGHUM and JU DOU By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Post-Mao China Not Connected

RESOURCES FILM REVIEW ESSAY documentary style with which filmmaker Zhang Yimou is normally Teaching Post-Mao China not connected. This style—long shots of city scenes filled with people Two Classic Films and a subdued color palette—contribute to the viewer’s understand - ing of life in China in the early 1990s. The village scenes could be By Melisa Holden from anytime in twentieth century China, as the extent of moderniza - tion is limited. For example, inside peasants’ homes, viewers see Introduction steam spewing from characters’ mouths because of the severe cold The Story of Qiu Ju and Beijing Bicycle are two films that have been and lack of central heating. However, when Qiu Ju travels to the ur - used in classrooms since they were produced (1992 and 2001, respec - banized areas, it becomes obvious that the setting is the late twentieth tively). Today, these films are still relevant to high school and under - century. The film was shot only a couple of years after the Tiananmen graduate students studying history, literature, and related courses Square massacre in 1989. Zhang’s previous two films ( Ju Dou and about China, as they offer a picture of the grand scale of societal Raise the Red Lantern ) had been banned in China, but with The Story change that has happened in China in recent decades. Both films il - of Qiu Ju , Zhang depicts government officials in a positive light, lustrate contemporary China and the dichotomy between urban and therefore earning the Chinese government’s endorsement. One feels rural life there. The human issues presented transcend cultural an underlying tension through Qiu Ju’s search for justice, as if it is not boundaries and, in the case of Beijing Bicycle , feature young charac - only justice for her husband’s injured body and psyche, but also jus - ters that are the age of US students, allowing them to further relate to tice supposedly found through democracy. -

Perspectives in Flux

Perspectives in Flux Red Sorghum and Ju Dou's Reception as a Reflection of the Times Paisley Singh Professor Smith 2/28/2013 East Asian Studies Thesis Seminar Singh 1 Abstract With historical and critical approach, this thesis examined how the general Chinese reception of director Zhang Yimou’s Red Sorghum and Ju Dou is reflective of the social conditions at the time of these films’ release. Both films hold very similar diegeses and as such, each generated similar forms of filmic interpretation within the academic world. Film scholars such as Rey Chow and Sheldon Lu have critiqued these films as especially critical of female marginalization and the Oedipus complex present within Chinese society. Additionally, the national allegorical framing of both films, a common pattern within Chinese literary and filmic traditions, has thoroughly been explored within the Chinese film discipline. Furthermore, both films have been subjected to accusations of Self-Orientalization and Occidentalism. The similarity between both films is undeniable and therefore comparable in reference to the social conditions present in China and the changing structures within the Chinese film industry during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Although Red Sorghum and Ju Dou are analogous, each received almost opposite reception from the general Chinese public. China's social and economic reform, film censorship, as well as the government’s intervention and regulation of the Chinese film industry had a heavy impact upon each film’s reception. Equally important is the incidence of specific events such as the implementation of the Open Door policy in the 1980s and 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre. -

Foreignizing Translation on Chinese Traditional Funeral Culture in the Film Ju Dou

ISSN 1923-1555[Print] Studies in Literature and Language ISSN 1923-1563[Online] Vol. 15, No. 1, 2017, pp. 47-50 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/9758 www.cscanada.org Foreignizing Translation on Chinese Traditional Funeral Culture in the Film Ju Dou PENG Xiamei[a],*; WANG Piaodi[a] [a]School of Foreign Languages, North China Electric Power University, Since Red Sorghum, the first film directed by him has Beijing, China. won the Golden Bear on February 23th, 1988, Zhang and *Corresponding author. his films produced a series of surprises for the Chinese Supported by The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central people and the world (Ban, 2003). He was said to be one Universities (JB2017074). of the most advanced figures in Chinese movies, and his films are regarded as a symbol of Chinese contemporary Received 15 April 2017; accepted 17 July 2017 culture. Published online 26 July 2017 In Zhang’s films, you’ll see a profound understanding of Chinese traditional feudal consciousness and strong Abstract critical spirit, which proves to be a strong sense of China is a country with more than five thousand years of history and life consciousness. It’s a peculiar landscape traditional cultures, which is broad and profound. With the of traditional folk customs and also praises for women’s increasing international status of China in recent years, rebellious spirit. The constant exploration and innovation more and more countries are interested in China and its in the film style and language represent the rise of a traditional culture as well. Film and television works, as new film trend. -

La Sociedad China a Través De Su Cine

E.G~oooo OCIOO 1'11 ~ ,qq~ ~ QC4 (j) 1q~t Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey Campus Eugenio Garza Sada La sociedad china a través de su cine Tesis presentada como requisito parcial para optar al título de Maestro en Educación con especialidad en Humanidades Autor: Ernesto Diez-Martínez Guzmán Asesor: Dr. Víctor López Villafañe Monterrey, N.L. abril de 1997 INTITUTO TECNOLOGICO Y DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES DE MONTERREY CAMPUS EUGENIO GARZA SADA La sociedad china a través de su cine Tesis presentada como requisito parcial para optar al título de Maestro en Educación con especialidad en Humanidades Autor: Ernesto Diez-Martínez Guzmán Asesor: Dr. Victor López Villafañe Monterrey, N.L. abril de 1997. A Martha, Alberto y Viridiana, por el tiempo robado. i Reconocimientos Al Dr. Victor López Villafañe, por el interés en este trabajo y por las palabras de aliento. Al ITESM Campus Sinaloa, por el apoyo nunca regateado. i i Resumen Tesis: "El cine chino a través de su cine". Autor: Ernesto Diez-Martínez Guzmán. Asesor: Dr. Víctor López Villafañe. La presente investigación. llamada "La sociedad china a través de su cine", pretende arribar al conocimiento de los mecanismos sociales, culturales y de poder de la sociedad china en el siglo XX, todo ello a través del estudio de la cinematografía del país más poblado del mundo. Desde los albores de la industria hasta la inminente fusión de Hong Kong con la China continental, el cine ha sido un importantísimo medio cultural, de entretenimiento y de propaganda, que ha sido testigo y actor fundamental de las grandes transformaciones de este país. -

Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected]

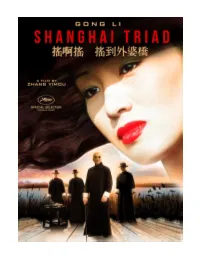

presents a film by ZHANG YIMOU starring GONG LI LI BAOTIAN LI XUEJIAN SUN CHUN WANG XIAOXIAO ————————————————————— “Visually sumptuous…unforgettable.” –New York Post “Crime drama has rarely been this gorgeously alluring – or this brutal.” –Entertainment Weekly ————————————————————— 1995 | France, China | Mandarin with English subtitles | 108 minutes 1.85:1 Widescreen | 2.0 Stereo Rated R for some language and images of violence DIGITALLY RESTORED Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Jimmy Weaver | Theatrical | (216) 704-0748 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Hired to be a servant to pampered nightclub singer and mob moll Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), naive teenager Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao) is thrust into the glamorous and deadly demimonde of 1930s Shanghai. Over the course of seven days, Shuisheng observes mounting tensions as triad boss Tang (Li Baotian) begins to suspect traitors amongst his ranks and rivals for Xiao Jinbao’s affections. STORY Shanghai, 1930. Mr. Tang (Li Boatian), the godfather of the Tang family-run Green dynasty, is the city’s overlord. Having allied himself with Chiang Kai-shek and participated in the 1927 massacre of the Communists, he controls the opium and prostitution trade. He has also acquired the services of Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), the most beautiful singer in Shanghai. The story of Shanghai Triad is told from the point of view of a fourteen-year-old boy, Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao), whose uncle has brought him into the Tang Brotherhood. His job is to attend to Xiao Jinbao. -

Accepted Manuscript

Performing Exoticism and the Transnational Reception of World Cinema Daniela Berghahn, Royal Holloway, University of London Professor of Film Studies, Dr. phil. Department of Media Arts, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham Hill, Egham, Surrey, TW20 0EX, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Abstract This article examines why exoticism is central to thinking about the global dynamics of world cinema and its transnational reception. Offering a theoretical discussion of exoticism, alongside the closely related concepts of autoethnography and cultural translation, it proposes that the exotic gaze is a particular mode of aesthetic perception that is simultaneously anchored in the filmic text and elicited in the spectator in the process of transnational reception. Like world cinema, exoticism is a travelling concept that depends on mobility and the crossing of cultural boundaries to come into existence. The visual pleasure afforded by exotic cinema’s sumptuous style is arguably the chief vehicle that allows world cinema to travel and be understood, or misunderstood, as the case may be, by transnational audiences who are potentially disadvantaged by a hermeneutic deficit of culturally specific knowledge when trying to understand films from outside their own cultural sphere. Dieser Artikel untersucht, warum der Exotismus von zentraler Bedeutung ist, um die globale Dynamik des World Cinema und seine transnationale Rezeption zu verstehen. Indem er eine Theorie des Exotismus vorlegt, und zugleich auf die eng verwandten Begriffe der Autoethnografie und der kulturellen Übersetzung eingeht, stellt er die These auf, dass es sich 1 beim exotischen Blick um eine besondere Form ästhetischer Wahrnehmung handelt, die einerseits im filmischen Text verankert ist und andererseits bei der transnationalen Rezeption im Zuschauer ausgelöst wird. -

A Cultural Study of the Portrayal of Leading Women in Zhang Yimou Films

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 2019 Unveiling Identities: A Cultural Study of the Portrayal of Leading Women in Zhang Yimou Films Patrick McGuire University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Ethnic Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation McGuire, Patrick, "Unveiling Identities: A Cultural Study of the Portrayal of Leading Women in Zhang Yimou Films" (2019). Dissertations. 1736. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1736 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNVEILING IDENTITIES: A CULTURAL STUDY OF THE PORTRAYAL OF LEADING WOMEN IN ZHANG YIMOU FILMS by Patrick Dean McGuire A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Communication at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Dr. Christopher Campbell, Committee Chair Dr. Phillip Gentile Dr. Cheryl Jenkins Dr. Vanessa Murphree Dr. Fei Xue ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Christopher Dr. John Meyer Dr. Karen S. Coats Campbell Director of School Dean of the Graduate School Committee Chair December.2019 COPYRIGHT BY Patrick Dean McGuire 2019 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT It is imperative to recognize the ongoing collaborations of filmmakers from different countries. -

Cultural Review: Viewing Hero

Cultural Review ence, will assiduously avoid any topic or either of these. Its story takes place theme that might offend the values of its against a real historical backdrop (as the 2005 target audience. The theme espoused by director has made a point of emphasizing), Viewing Hero: . 2, Hero is an affront to traditional scholarly but the story itself is fictional. The crux of A Conversation about History, NO thought, as well as to modern human rights the matter is that the attempted assassina- Art and Responsibility mentality; it does not conform to the values tion of the Qin Emperor, which is Hero’s and standards of Chinese or of foreigners. main storyline, does not conform to either BY SHARON HOM AND HU PING If Zhang Yimou failed to consider how emotional or historical reality. Not only is it provocative the theme of Hero would be to not historical, it is actually ahistorical. Sharon Hom: One of China’s “Fifth Genera- the values of others, he was acting in igno- An artistic fiction that counters history tion” filmmakers,1 Zhang Yimou is one of rance. If he knowingly violated these val- typically expresses its creator’s extreme dis- two mainland Chinese directors2 who have ues, this suggests that what he was satisfaction with history, and indicates that RIGHTS FORUM achieved artistic acclaim internationally. producing was not an entertainment film, real events have violated the author’s values His work has been banned, criticized, lion- but a morality play. and standards. When the creator’s dissatis- CHINA ized and debated domestically within Defenders of Hero also say that it is faction with historical reality is so strong that China, most recently following the release merely a commercial film aimed at making he feels that producing a work in confor- 91 of Hero.3 In addition to his international money. -

Alternate Paeans of Desire: the Chinese Film JU DOU and the American Play DESIRE UNDER the ELMS

Intercultural Communication Studies XIII: 3 2004 Zeng Alternate Paeans of Desire: the Chinese Film JU DOU and the American Play DESIRE UNDER THE ELMS Li Zeng University of Louisville Abstract The internationally acclaimed Chinese film Ju Dou (1990), directed by Zhang Yimou, is about a love triangle among a dye-house master with impotence, his young wife, and his nephew apprentice. Although the film is adapted from Liu Heng’s novella Fuxi fuxi (1988) whose title draws our attention to the Chinese myth about Fuxi and Nuwa–two siblings becoming spouses who created humankind, the incestuous relationship in the film reminds us of that in Eugene O’Neill’s play, Desire Under the Elms (1924). The situation of Ju Dou, as this paper sees, is the Ephraim-Abbie-Eben plot of the Desire Under the Elms which is modeled upon the Hippolytos-Phaidra-Theseus relationship in Greek mythology. Apart from the similarity of plot scenario, there is technical similarity between the two works. In comparing Ju Dou with Desire Under the Elms, the paper suggests that these two artists emotionally revealed different aspects of their view of life through similar dramatic plots and characters and that O’Neill not only influenced modern Chinese playwrights in the early decades of the twentieth-century but might still be in rapport with Chinese culture in the post-Mao era. INTRODUCTION Ju Dou is one of the famous Chinese films by Zhang Yimou, an internationally renowned film director in contemporary China. Financed in part by foreign capital, Ju Dou came out in 1990.1 Although the Chinese government banned the film domestically for two years and attempted to withdraw it from international competitions, Ju Dou was widely shown abroad, received the Luis Bunuel Award at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival, and became the first Chinese movie to be nominated for an Oscar in 1991.2 An internationally acclaimed work, Ju Dou has fascinated a large number of audiences, film critics, and scholars of Chinese culture over the past decade. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 184 2nd International Conference on Education Science and Economic Management (ICESEM 2018) Studies of the National Subjectivity of Chinese Films: History, Status quo and Multi-dimensional Construction Zhang Xianxi School of Communication, Zaozhuang University No.1 Bei’an Road, Shizhong District, Zaozhuang, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—Starting from the studies of nationalization of Chinese films, the studies of the national subjectivity of Chinese II. HISTORY OF THE STUDIES OF NATIONAL SUBJECTIVITY films have become the hotspot and frontier of the current OF CHINESE FILMS academic research in China since the success of the International The current studies of national subjectivity in China focus Symposium of Chinese Films and National Subjectivity in 2007. on the Chinese philosophy and the subjectivity of Chinese Based on the history and status quo of national subjectivity culture. In contrast, the national subjectivity studies of Chinese research, this paper puts forward the strategies of constructing the subjectivity of Chinese films from the perspectives of films, although having become the research hotspot and inheriting the Chinese cultural genes, promoting Chinese style frontier, have made comparatively few representative and highlighting Chinese spirits. achievements. Historically, the national subjectivity studies of Chinese films can be traced back to the studies of Keywords—Chinese Film School; Subjectivity; Cultural genes; nationalization of Chinese films which began from the early The Chinese styles; The Chinese spirits 1960s when there was a relatively loose context for artistic creation. In the paper To Look for Treasures in the Chinese Tradition: Learning Notes on the National Forms of Films I. -

HERO in the WEST and EAST by FANG ZHANG a Thesis Submitted

HERO IN THE WEST AND EAST BY FANG ZHANG A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Communication May 2009 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Peter Brunette, Ph.D., Advisor Examining Committee: Mary M. Dalton, Ph.D. Shi Yaohua, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research spanned over two semesters and would not be in the current form without generous help and encouragement from many of my mentors and friends. First, my deepest appreciation, thanks and respect go to Dr. Brunette, who not only advised me on this project but throughout my graduate career at Wake Forest University. Even though we have different opinions in 2008 presidential election and political massages in Chinese films, yet we enjoy much more joyful moments of “great minds think alike,” such as sharing the excellent articles from New Yorker and Hollywood Reporter. Thank him for the trust, support and guidance throughout these years. I am looking forward to his new book on Michael Haneke. Dr. Dalton, Dr. Louden, Dr. Beasley, Dr. Giles, Dr. Hazen and Beth Hutchens from Department of Communication, they are true inspirations not only because of their work in professional careers but also how they live their lives. I am thankful for the time listening to them, working with them, and learning from them. Last year, Dr Beasley got married and Dr Krcmer had a new family member—a lovely girl, best wishes for them. This list of acknowledgements would not be complete without mentioning three of my best friends, Laura Wong, Rebecca Hao and Zhang Wei, without whose constant support and assistance, I cannot survive the hard time or get confident in facing the coming challenges. -

The Representation of Motherhood in Post-Socialist Chinese Cinema

Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol 2, No 1 (2009) ARTICLE The Representation of Motherhood in Post-Socialist Chinese Cinema HUILI HAO, University of Sussex ABSTRACT Critics agree that the mother figure has consistently played an important role in Chinese cinema. But this topic has rarely been addressed. This paper will explore what others mother figures can be found in Chinese cinema from 1990 onwards besides the mainstream representation of motherhood that carries both the national modernization and the women’s traditional merits. In this paper, I shall investigate three paradigms of the representation of motherhood in Chinese films since 1990s. The first paradigm is the Exemplary Mother, which seeks to construct the main discourse of motherhood through complying with the main-stream ideology. The second paradigm is the Transgressive Mother, which resists the myth of the good mother. The third paradigm the Consistent Mother in Chinese feminist films, which concerns the mother’s subjectivity and experience, emphasizing the strong bonding between mother and daughter, and normally giving them a positive future. KEYWORDS Representation; motherhood; Chinese film Introduction Post-socialist China has seen economic and political changes that have affected all areas of Chinese society, including discourses around gender. With regards to motherhood, the discourse has become more complicated than during the Mao era. Heterodox discourses on motherhood, which had almost disappeared from the representational system (including film) prior to 1979, has now returned. This paper studies the representation of motherhood in the films of post-socialist China in relation to the multiple discourses on motherhood during this same period, followed by a discussion of the relationship between these discourses, especially their relationship with the representation of motherhood in films.