John Cardinal Newman and Ex Corde Ecclesiae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Centrality of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass at Christendom College

THE CENTRALITY OF THE HOLY SACRIFICE OF THE MASS AT CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE The Church teaches that the Eucharist is “the source and summit of the Christian life”1 and that the celebration of the Mass “is a sacred action surpassing all others. No other action of the Church can equal its efficacy.”2 That is why “as a natural expression of the Catholic identity of the University. members of this community . will be encouraged to participate in the celebration of the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, as the most perfect act of community worship.”3 Those central truths are taught and lived at Christendom College, a “Catholic coeducational college institutionally committed to the Magisterium”4 of the Church, in the following ways: The Celebration of the Sacred Liturgy The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass • Mass is offered frequently: twice daily Monday through Thursday, three times on MONDAY (Friday), twice on Saturday, and once on Sunday (the day on which we gather as one family). • Mass in the Roman Rite is celebrated in all the ways offered by the Church: in the Ordinary Form in both English and Latin, and in the Extraordinary Form from one to three times per week, as circumstances permit. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated with the solemnity appropriate to each feast, utilizing worthy sacred vessels and vestments, and drawing upon the Church’s rich tradition of chant, polyphony, and hymnody. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated reverently and with rubrical fidelity. • No classes or other activities are scheduled during Mass times. • The majority of the College community attends daily Mass regularly and with great devotion. -

Institutions and Dynamics of Learned Exchange

chapter 26 Institutions and Dynamics of Learned Exchange Kenneth Gouwens Throughout the early modern period Rome was a major center of literary pro- duction. With but few interruptions, popes and cardinals played key roles as patrons and hosts of gatherings of the learned. Among libraries, the Vatican came to hold pride of place.1 In the later 16th century, when concerns about or- thodoxy circumscribed both access and subjects of inquiry there, other collec- tions, both private and public, substantially compensated for those constraints. Their variety and in some cases specialization helped to diffuse research and to promote discussions among specialists. Academies, finally, were important sites of literary performance and learned conversation.2 Those of the early 16th century were few but influential, providing opportunities for interaction not only among literati and patrons, but also with artists and architects including Raphael and Bramante. Church authorities often figured prominently in the academies that proliferated in Seicento Rome, many of which had specific foci. The Accademia degli Arcadi (Arcadians), founded in 1690, would become a meta-academy of sorts, and its self-conscious redirection of taste would help to initiate a shift away from the stylistic flamboyance that had dominated the 17th century. The present chapter treats these aspects of Roman learned cul- ture in three periods, the points of inflection marked by the election of trans- formative popes: Alexander VI in 1492; Paul IV in 1555; and Urban VIII in 1623 to the death of Innocent XII in 1700. 1 Prelude: the Pursuit of Letters in Early Renaissance Rome During the pontificates of Martin V (r.1417–31), whose election ended decades of schism, and Eugenius IV (r.1431–55), papal patronage drew to Rome brilliant 1 See the new official history of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana in seven volumes, which began publication in 2010. -

Statement by His Excellency Archbishop Silvano Tomasi

Statement by His Excellency Archbishop Silvano Tomasi, Permanent Observer of the Holy See to the United Nations and Other International Organizations in Geneva at the 26th Session of the Human Rights Council Item 3 - Independent Expert on Human Rights and International Solidarity Geneva, 13 June 2014 Mr. President, As States and civil society continue intensive efforts to plan strategically the future development of our planet and its peoples, we continue to be burdened, at this moment of history, with a long-term financial crisis. It has deeply affected not only those high-income economies where it was initiated, but also those struggling economies that depend so much on global opportunities in order to emerge from centuries-long oppression by abject poverty or by the remnants of colonialism, or by more recent unjust trade policies. Moreover, in view of the escalating conflicts between and within various States, the human family often appears incapable of safeguarding peace and harmony in our troubled world. Nor can we ignore the destructive effects wrought by climate change both on the natural patrimony of this earth and on all women and men who have been made the stewards of creation. Among the diverse causes of human suffering we must also consider the role of personal greed, which leads to the literal “enslavement” of millions of women, children, and men in clear situations of abuse and total disregard for the human person. Similarly, we must also consider the situation of people in low-paid employment who work under extremely negative conditions from which they see no way of escape. -

Spring 2020 Booklist Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family

Spring 2020 Booklist Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family JPI 510/729 Theological Anthropology McCarthy • Compendium of readings (available through Cognella) • Burns, J., Ed. Theological Anthropology. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981. • Balthasar, Hans Urs. The Christian State of Life. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1983. • ______. Theo-Drama II, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990. ISBN 0898702879 • ______. Theo-Drama III. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 11992. ISBN 089870295X. • De Lubac, H. The Drama of Atheist Humanism. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1995. ISBN: 089870443X • De Lubac, H. A Brief Catechesis on Nature and Grace. Ignatius Press, 1984. ISBN: 0898700353 • John Paul II. Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body. Pauline, 1997. • Schmitz, K. The Gift: Creation. Marquette University Press, Milwaukee, 1982. • Scola. The Nuptial Mystery. Trans. M. Borras. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans, 2005. • Spaemann, R. Essays in Anthropology – Variations on a Theme. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2010. JPI 532/707 Biblical Theology of Marriage and Family (OT) Atkinson • Holy Scriptures [The most recent edition of Ignatius Press’ RSV is particularly good.] • Biblical and Theological Foundation of the Family, Joseph Atkinson (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2014). • Jean-Baptiste Edart (with Himbaza and Schenker). The Bible on the Question of Homosexuality. (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2012). JPI 550/850 Gender and the Sexual Difference D.L. Schindler • Compendium of readings (available through Cognella) • Simon Baron-Cohen, The Essential Difference. (New York: Basic Books, 2003). • John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them: Theology of the Body. • Eve Tushnet, Gay and Catholic (Ave Maria Press, 2014). -

Reconstruction Or Reformation the Conciliar Papacy and Jan Hus of Bohemia

Garcia 1 RECONSTRUCTION OR REFORMATION THE CONCILIAR PAPACY AND JAN HUS OF BOHEMIA Franky Garcia HY 490 Dr. Andy Dunar 15 March 2012 Garcia 2 The declining institution of the Church quashed the Hussite Heresy through a radical self-reconstruction led by the conciliar reformers. The Roman Church of the late Middle Ages was in a state of decline after years of dealing with heresy. While the Papacy had grown in power through the Middle Ages, after it fought the crusades it lost its authority over the temporal leaders in Europe. Once there was no papal banner for troops to march behind to faraway lands, European rulers began fighting among themselves. This led to the Great Schism of 1378, in which different rulers in Europe elected different popes. Before the schism ended in 1417, there were three popes holding support from various European monarchs. Thus, when a new reform movement led by Jan Hus of Bohemia arose at the beginning of the fifteenth century, the declining Church was at odds over how to deal with it. The Church had been able to deal ecumenically (or in a religiously unified way) with reforms in the past, but its weakened state after the crusades made ecumenism too great a risk. Instead, the Church took a repressive approach to the situation. Bohemia was a land stained with a history of heresy, and to let Hus's reform go unchecked might allow for a heretical movement on a scale that surpassed even the Cathars of southern France. Therefore the Church, under guidance of Pope John XXIII and Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg, convened in the Council of Constance in 1414. -

Important Church Writings…

Important Church Writings… Official documents of the Catholic Church have evolved and differentiated over time, but commonly come from four basic sources: 1) Papal documents, issued directly by the Pope under his own name; 2) Church Council documents, issued by ecumenical councils of the Church and now promulgated under the Pope's name, taking the same form as common types of papal documents; and 3) Bishops documents, issued either by individual bishops or by national conferences of bishops. The types of each are briefly explained below. Not all types of documents are necessarily represented currently in this Bibliography. The level of magisterial authority pertaining to each type of document - particularly those of the Pope - is no longer always self- evident. A Church document may (and almost always does) contain statements of different levels of authority commanding different levels of assent, or even observations which do not require assent as such, but still should command the respect of the faithful. The Second Vatican Council, speaking through Lumen Gentium (The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church) identified as many as four different kinds of authority (n. 25). Those affirmations of the Second Vatican Council that recall truths of the faith naturally require the assent of theological faith, not because they were taught by this Council but because they have already been taught infallibly as such by the Church, either by a solemn judgment or by the ordinary and universal Magisterium. So also a full and definitive assent is required for the other doctrines set forth by the Second Vatican Council which have already been proposed by a previous definitive act of the Magisterium. -

Saint John Paul II

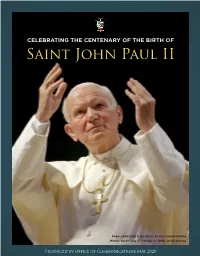

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission. -

Download Download

Implementing the Principles of the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Catholic Church in Catholic Higher Education1 His Eminence Renato Raffaele Cardinal Martino The purpose of this discussion is to share a refl ection on the imple- mentation of Catholic Social Teaching (CST) in the ministry of Catholic higher education. In particular, I wish to highlight the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church2 that was completed by the Pontifi cal Council for Justice and Peace at the request of the Servant of God, Pope John Paul II. Designed to be a user-friendly synthesis of the principles of CST, the Compendium has proven to be an extremely practical and substantial resource. It has now been translated into 40 different lan- guages and is widely available throughout the world. In a certain sense, the Social Doctrine of the Catholic Church has been called “the Church’s best kept secret.” Why is this the case? Before the publication of the Compendium, perhaps because the social teach- ings of the popes were responding to specifi c situations (such as the cir- cumstances of the workers at the end of nineteenth century examined by Pope Leo XIII in his Encyclical Rerum novarum3), a well-structured exposition of the social doctrine of the Church did not exist. It was not until 1999 that Pope John Paul II, in his exhortation Ecclesia in America4, promised a document that would synthesize the social doc- trine of the Church. He then asked the Pontifi cal Council for Justice and Peace to prepare such a document—the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church—which was fi rst released on October 25, 2004. -

Catholic Social Ethics Convener: Raymond Ward, Barry University Moderator: Christine Fire Hinze, Fordham University Presenters: Meghan J

CTSA Proceedings 69 / 2014 FROM COMFORT AND AMBITION TO UNITY ACROSS DIFFERENCE: THE CHALLENGE OF SOLIDARITY—SELECTED SESSION Topic: Catholic Social Ethics Convener: Raymond Ward, Barry University Moderator: Christine Fire Hinze, Fordham University Presenters: Meghan J. Clark, St. John’s University Raymond Ward, Barry University Meghan Clark began the session with a paper on “An Obligation to be Uncomfortable: Pope Francis and the Challenge of Solidarity (for the Developed World).” In it she examined statements that Francis has made in his early papacy concerning solidarity and argued that they are best characterized as a call to uncomfortableness on the part of the privileged rooted in his identification of the incarnate Christ with the poor. Clark noted that solidarity is a multifaceted feature of Catholic social ethics, variously explained as “an attitude, a duty, a principle, and . most comprehensively approached as a virtue.” In the words of Pope Paul II, it is “a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say the good of all and of each individual because we are really all responsible for all” (Solicitudo rei socialis, 38). For Francis, Clark argues, the major impediment to the development of this virtue among people in the developed world is their resistance to feeling the moral discomfort that comes with acknowledging overwhelming social injustice: “the problem is the inability to knowingly and willingly be uncomfortable . This is a necessary first step toward collaborating for structural change and prompting critical self-reflection into our own participation and complicity in those sinful structures.” To illustrate Francis’s view of solidarity, Clark highlighted four papal addresses: regarding refugees on the Italian island of Lampedusa, during World Youth Day in the Rio de Janeiro favela of Varginha, at the Jesuit Refugee Center in Rome, and during his pastoral visit with inmates, the poor and unemployed youth in Cagliari, Sardinia. -

The Holy See, Social Justice, and International Trade Law: Assessing the Social Mission of the Catholic Church in the Gatt-Wto System

THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT-WTO SYSTEM By Copyright 2014 Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma Submitted to the graduate degree program in Law and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D) ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) _______________________________ Professor Virginia Harper Ho (Member) ________________________________ Professor Uma Outka (Member) ________________________________ Richard Coll (Member) Date Defended: May 15, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT- WTO SYSTEM by Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) Date approved: May 15, 2014 ii ABSTRACT Man, as a person, is superior to the state, and consequently the good of the person transcends the good of the state. The philosopher Jacques Maritain developed his political philosophy thoroughly informed by his deep Catholic faith. His philosophy places the human person at the center of every action. In developing his political thought, he enumerates two principal tasks of the state as (1) to establish and preserve order, and as such, guarantee justice, and (2) to promote the common good. The state has such duties to the people because it receives its authority from the people. The people possess natural, God-given right of self-government, the exercise of which they voluntarily invest in the state. -

Popes in History

popes in history medals by Ľudmila Cvengrošová text by Mons . Viliam Judák Dear friends, Despite of having long-term experience in publishing in other areas, through the AXIS MEDIA company I have for the first time entered the environment of medal production. There have been several reasons for this decision. The topic going beyond the borders of not only Slovakia but the ones of Europe as well. The genuine work of the academic sculptress Ľudmila Cvengrošová, an admirable and nice artist. The fine text by the Bishop Viliam Judák. The “Popes in history” edition in this range is a unique work in the world. It proves our potential to offer a work eliminating borders through its mission. Literally and metaphorically, too. The fabulous processing of noble metals and miniatures produced with the smallest details possible will for sure attract the interest of antiquarians but also of those interested in this topic. Although this is a limited edition I am convinced that it will be provided to everybody who wants to commemorate significant part of the historical continuity and Christian civilization. I am pleased to have become part of this unique project, and I believe that whether the medals or this lovely book will present a good message on us in the world and on the world in us. Ján KOVÁČIK AXIS MEDIA 11 Celebrities grown in the artist’s hands There is one thing we always know for sure – that by having set a target for himself/herself an artist actually opens a wonderful world of invention and creativity. In the recent years the academic sculptress and medal maker Ľudmila Cvengrošová has devoted herself to marvellous group projects including a precious cycle of male and female monarchs of the House of Habsburg crowned at the St. -

Sunday, May 14 Fifth Sunday of Easter

SUNDAY , M AY 14 FIFTH SUNDAY OF EASTER Congratulations to our 2017 First Communicants! Samuel James Aamot Nicholas Charles Earl Ahrendt Madeleine Louise Berthiaume Peter Alexander Brownell Katelyn Patricia Campbell Seth Michael Capistrant Margaret Ann Coyne Savannah Paige Culbertson Sarah Grace Dettloff Thomas Ronald Draganowski Maria Christiana Calma Duggan James Michael Ekern Isaac Thomas Ekern Gregory John Feeney Ava Noelle Flood Augustine Timothy James Hartwell Caleb Matthew Michael Heffron Maria Faustina Ives Victoria Isabel Jaimes Joseph MatthewJunkert Olivia Gianna Kane Jenna Margaret Koontz Jane Marie Kuwata Luke Daniel Macdonald Anthony Joseph McNamara Henry Nicholas Misenor Mark Joseph Moriarty Samuel James Oglesbee Amaya Teresa Perez Thomas Augustine Plasch Thomas Aquinas Reandeau Rocco Pio Rinaldi Maria Janet Schaeffer Lukas Craig Scherping Simon William Scott Cyprian Patrick Slattery Anthony Gerard Steiner Joseph Timothy St. Martin Darren Salvador Valento Payasha Lucy Vang Ignatius Christian Athanasius Washburn Gemma Rose Weisbecker Madeline Marie Wernet Brianna Yang Seraphim Yang 535 Thomas Ave. | Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 | 651.925.8800 | www.churchofsaintagnes.org PASTOR’S COLUMN TODAY AT SAINT AGNES Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ, The Church of Saint Agnes wishes all mothers of the parish a Happy and Blessed Mother’s Day. Having discussed the role of key stakeholders for the school CHORALE & ORCHESTRA NOTES in Appendix A, we now turn our attention to essential prac- Charles Gounod, Messe Solennelle (Saint Cecelia) (1855) tices Saint Agnes School will commit itself to in support of our Philosophy of Education. The music for this Mass is sponsored by Dr. Linda Long in honor of Rev. James S. Stromberg APPENDIX B: Specific Commitments in Service of Our Mis- Composer Charles Gounod (1818-1893) was a practicing sion Catholic who as a youth contemplated becoming a priest.