Important Church Writings…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plenary Indulgence

Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers Pope Francis Proclaims Plenary Indulgence Affirming the Response to the PAENITENIARIA 10th Year Jubilee Plenary Indulgence Honoring Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers, by Apostolic Papal Decree a Plenary Indulgence is granted to faithful making pilgrimage to Lourdes or experiencing Lourdes in a Virtual Pilgrimage with North American Lourdes Volunteers by fulfilling the usual norms and conditions between July 16, 2013 thru July 15, 2020. APOSTOLICA Jesus Christ lovingly sacrificed Himself for the salvation of humanity. Through Baptism, we are freed from the Original Sin of disobedience inherited from Adam and Eve. With our gift of free will we can choose to sin, personally separating ourselves from God. Although we can be completely forgiven, temporal (temporary) consequences of sin remain. Indulgences are special graces that can rid us of temporal punishment. What is a plenary indulgence? “An indulgence is a remission before God of the temporal punishment Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers due to sins whose guilt has already been forgiven.” (CCC 1471) There Public Association of the Christian Faithful and First Hospitality of the Americas are two types of indulgences: plenary and partial. A plenary indulgence www.LourdesVolunteers.org [email protected] removes all of the temporal punishment due to sin; a partial indulgence (315) 476-0026 FAX (419) 730-4540 removes some but not all of the temporal punishment. © 2017 V. 1-18 What is temporal punishment for sin? How can the Church give indulgences? Temporal punishment for sin is the sanctification from attachment to sin, The Church is able to grant indulgences by the purification to holiness needed for us to be able to enter Heaven. -

The Centrality of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass at Christendom College

THE CENTRALITY OF THE HOLY SACRIFICE OF THE MASS AT CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE The Church teaches that the Eucharist is “the source and summit of the Christian life”1 and that the celebration of the Mass “is a sacred action surpassing all others. No other action of the Church can equal its efficacy.”2 That is why “as a natural expression of the Catholic identity of the University. members of this community . will be encouraged to participate in the celebration of the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, as the most perfect act of community worship.”3 Those central truths are taught and lived at Christendom College, a “Catholic coeducational college institutionally committed to the Magisterium”4 of the Church, in the following ways: The Celebration of the Sacred Liturgy The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass • Mass is offered frequently: twice daily Monday through Thursday, three times on MONDAY (Friday), twice on Saturday, and once on Sunday (the day on which we gather as one family). • Mass in the Roman Rite is celebrated in all the ways offered by the Church: in the Ordinary Form in both English and Latin, and in the Extraordinary Form from one to three times per week, as circumstances permit. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated with the solemnity appropriate to each feast, utilizing worthy sacred vessels and vestments, and drawing upon the Church’s rich tradition of chant, polyphony, and hymnody. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated reverently and with rubrical fidelity. • No classes or other activities are scheduled during Mass times. • The majority of the College community attends daily Mass regularly and with great devotion. -

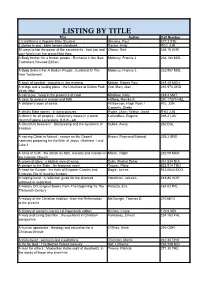

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

A Pope of Their Own

Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church UPPSALA STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY 1 About the series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. The series includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form. For a list of available titles, see end of the book. About the author Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with focus on colonial Latin America. Among his monographs are Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines (2015) and Church Life between the Metropolitan and the Local: Parishes, Parishioners and Parish Priests in Seventeenth-Century Mexico (2011). Personal web site: www.magnuslundberg.net Uppsala Studies in Church History 1 Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church Lundberg, Magnus. A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Uppsala Studies in Church History 1.Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, 2017. ISBN 978-91-984129-0-1 Editor’s address: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, Church History, Box 511, SE-751 20 UPPSALA, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Contents Preface 1 1. Introduction 11 The Religio-Political Context 12 Early Apparitions at El Palmar de Troya 15 Clemente Domínguez and Manuel Alonso 19 2. -

What Is an Apostolic Exhortation? It's a Papal Document That Exhorts

‘Evangelii Gaudium’ and ‘Laudato Si’ All creation “groans in travail” (Rom 8:22) How are we called to a deeper conversion? What is an apostolic exhortation? A papal document that encourages the faithful to implement a particular aspect of the Church’s life and teaching. What is an encyclical? A part of the ordinary magisterium (teaching authority) of the Church Evangelii Gaudium (English: The Joy of the Gospel) is a 2013 apostolic exhortation by Pope Francis on "the church's primary mission of evangelization in the modern world." Evangelii Gaudium What is Pope Francis’ main message in Evangelii Gaudium? The principal theme involves the need for a joyful proclamation of the Gospel to the entire world. “…an Apostolic Exhortation written around the theme of Christian joy in order that the Church may rediscover the original source of evangelisation in the contemporary world” In Evangelii Gaudium Pope Francis’ expresses: Concern that the Church is becoming more judgmental than merciful. He wants a Church that has the outgoing spirit of the pilgrim, as opposed to a Church closed in on itself, languishing in ‘institutional inertia’ He worries that some Catholics have become too attached to the external forms of the faith, while their hearts have grown cold. 6 insights provided by Pope Francis, in EG: 1 God’s inexhaustible mercy. 2 The way of beauty. 3 The ‘revolution of tenderness.’ 4 Humility before Scripture. 5 The wounds of Christ. 6 ‘Faith is always a cross.’ God’s inexhaustible mercy. We are called to renew our commitment to mercy as an external work “The Eucharist, although it is the fullness of sacramental life, is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.” The way of beauty. -

The Christian Remains of the Seven Churches of the Apocalypse

1974, 3) THE BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST 69 The Christian Remains of the Seven Churches of the Apocalypse OTTO F. A. MEINARDU S Athens, Greece Some months ago, I revisited the island of Patmos and the sites of the seven churches to which letters are addressed in the second and third chap- ters of the book of Revelation. What follows is a report on such Christian remains as have survived and an indication of the various traditions which have grown up at the eight locations, where, as at so many other places in the Orthodox and Latin world, piety has sought tangible localization. I set out from Piraeus and sailed to the island of Patmos, off the Turkish coast, which had gained its significance because of the enforced exile of God's servant John (Rev. 1:1, 9) and from the acceptance of the Revelation in the NT canon. From the tiny port of Skala, financial and tourist center of Patmos, the road ascends to the 11th century Greek Orthodox monastery of St. John the Theologian. Half way to this mighty fortress monastery, I stopped at the Monastery of the Apocalypse, which enshrines the "Grotto of the Revelation." Throughout the centuries pilgrims have come to this site to receive blessings. When Pitton de Tournefort visited Patmos in 1702, the grotto was a poor hermitage administered by the bishop of Samos. The abbot presented de Tournefort with pieces of rock from the grotto, assuring him that they could expel evil spirits and cure diseases. Nowadays, hundreds of western tourists visit the grotto daily, especially during the summer, and are shown those traditional features which are related in one way or another with the vision of John. -

Parish Administrative Manual

Parish Administrative Manual Diocese of Bridgeport March 2021 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS I INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE OF THE MANUAL………………………. 8 1. Calendar 2. Overview 3. Distribution 4. Parish Community II OFFICE OF THE BISHOP……………………………………………………………... 11 1. Overview 2. Calendar Requests for Bishop 2.1 Liturgical Celebrations 2.2 Non-Liturgical Events 3. Pastoral Year Calendar 4. Confirmation 4.1 Process III OFFICE OF THE CHANCELLOR…………………………………………………….. 14 1. Overview 2. Mass Census 3. Annual Statistical Summary 4. Official Catholic Directory 4.1 Tax-exempt Status 4.2 Public Charity Organizations IV SAFE ENVIRONMENT PROCESS………………………………………………….. 17 1. Overview 2. Reporting Suspected Abuse of a Minor or Vulnerable Adult 3. VIRTUS® Database 4. VIRTUS® Training and Requirements V EMPLOYMENT AND PERSONNEL PROCESSES……………………………. 20 1. Overview 2. Personnel Action Form Parish Employment Parish Administrative Manual Diocese of Bridgeport Issued March 2021 The entire contents of this Parish Administrative Manual © 2021 The Bridgeport Roman Catholic Diocesan Corporation. All rights reserved. 5 VI PARISH GOVERNANCE AND LEGAL ADMINISTRATION……………… 22 1. Overview 2. Religious Corporations 2.1 By-laws of the Corporation 2.2 Corporation Paperwork and Annual Meetings 3. Consultative Councils 3.1 Trustees 3.2 Finance Council 3.3 Pastoral Council 4. Leases 4.1 Lease Consent 4.2 Holy See Approval Process 5. Records 5.1 ParishSOFT 5.2 Sacramental Records 5.3 Parish Records 6. Tribunal VII FINANCE AND BUDGETING……………………………………………………… 31 1. Overview 2. Summary of Financial Accountability and Transparency 3. Reporting Timelines VIII FACILITIES AND OPERATIONS…………………………………………………… 33 1. Overview 2. Catholic Mutual Coverage Program and Assessment 3. Renovation of Sacred Space, Capital Improvements and Repairs 3.1 Diocesan Building and Sacred Arts Commission 3.2 Approval Process 4. -

Pope Francis to Issue Apostolic Letter on Ministry of Catechist

Pope Francis to issue apostolic letter on ministry of catechist Pope Francis will issue an apostolic letter next week on the ministry of catechist. The Holy See press office said May 5 that the papal letter, issued motu proprio (“on his own impulse”), would be presented at a press conference May 11. It described the apostolic letter, Antiquum ministerium, as the means “by which the ministry of catechist is instituted.” The Italian section of the Vatican News website said: “The motu proprio therefore will formally establish the ministry of catechist, developing that evangelizing dimension of the laity called for by Vatican II.” It noted that in a 2018 video message, Pope Francis said that the vocation of catechist “demands to be recognized as a true and genuine ministry of the Church, which we particularly need.” Further details will be unveiled at the news conference, which will take place at the Vatican. Archbishop Rino Fisichella, president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelization, and Bishop Franz-Peter Tebartz-van Elst, the Pontifical Council’s delegate for catechesis, will speak at the event. The Code of Canon Law (Can. 785) defines catechists as “lay members of the Christian faithful, duly instructed and outstanding in Christian life, who devote themselves to setting forth the teaching of the gospel and to organizing liturgies and works of charity under the direction of a missionary.” “Catechists are to be formed in schools designated for this purpose or, where such schools are lacking, under the direction of missionaries,” it says, according to a Catholic News Agency report. -

Contact: Joann Fox, Senior Communications Specialist Phone: 616-514-6067 Email: [email protected]

May 20, 2019 The Diocese of Grand Rapids’ Office of Communications shares the following reflection from Bishop Walkowiak regarding Vos estis lux mundi (“You are the light of the world. A city set on a hill cannot be hidden” Mt 5:14). The new Motu Proprio released by Pope Francis orders a worldwide response by the Church to the evil of sexual abuse: “I join my brother bishops in welcoming the directives of Vos estis lux mundi as a framework for empowering the global Church in responding to and reporting abuse. Especially important are its directives for reporting and dealing with allegations of abuse against cardinals, bishops, patriarchs, and heads of religious institutes, and holding accountable anyone who covers-up or fails to adequately respond to allegations of abuse. In addition, it requires reporting to and compliance with local law enforcement, establishes whistle-blower protections for those who come forward, and protects the rights of all persons involved. The release of this Motu Proprio just two months after the meeting of episcopal conference presidents in Rome, shows the Holy Father’s expectation for swift and far-reaching action to eliminate the crime and sin of sexual abuse from the Church. It also reflects his deep pastoral concern for victim-survivors, their families and the faithful throughout the world. Many elements of the Motu Proprio are already being followed in the United States through the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People and its essential norms, established in 2002. As an expansion of that work, the Diocese of Grand Rapids and other U.S. -

Apostolic Constitution "Anglicanorum Coetibus"

APOSTOLIC CONSTITUTION "ANGLICANORUM COETIBUS" "Jesus Prayed to the Father for the Unity of His Disciples" The constitution introduces a canonical structure that will allow groups of Anglicans to enter full communion with the Catholic Church while preserving elements of their spiritual and liturgical patrimony. * * * In recent times the Holy Spirit has moved groups of Anglicans to petition repeatedly and insistently to be received into full Catholic communion individually as well as corporately. The Apostolic See has responded favorably to such petitions. Indeed, the successor of Peter, mandated by the Lord Jesus to guarantee the unity of the episcopate and to preside over and safeguard the universal communion of all the Churches,[1] could not fail to make available the means necessary to bring this holy desire to realization. The Church, a people gathered into the unity of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit,[2] was instituted by our Lord Jesus Christ, as "a sacrament -- a sign and instrument, that is, of communion with God and of unity among all people."[3] Every division among the baptized in Jesus Christ wounds that which the Church is and that for which the Church exists; in fact, "such division openly contradicts the will of Christ, scandalizes the world, and damages that most holy cause, the preaching the Gospel to every creature."[4] Precisely for this reason, before shedding his blood for the salvation of the world, the Lord Jesus prayed to the Father for the unity of his disciples.[5] It is the Holy Spirit, the principle -

The Holy See

The Holy See POST-SYNODAL APOSTOLIC EXHORTATION ECCLESIA IN ASIA OF THE HOLY FATHER JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS, PRIESTS AND DEACONS, MEN AND WOMEN IN THE CONSECRATED LIFE AND ALL THE LAY FAITHFUL ON JESUS CHRIST THE SAVIOUR AND HIS MISSION OF LOVE AND SERVICE IN ASIA: "...THAT THEY MAY HAVE LIFE, AND HAVE IT ABUNDANTLY" (Jn 10:10) INTRODUCTION The Marvel of God's Plan in Asia1. The Church in Asia sings the praises of the "God of salvation" (Ps 68:20) for choosing to initiate his saving plan on Asian soil, through men and women of that continent. It was in fact in Asia that God revealed and fulfilled his saving purpose from the beginning. He guided the patriarchs (cf. Gen 12) and called Moses to lead his people to freedom (cf. Ex 3:10). He spoke to his chosen people through many prophets, judges, kings and valiant women of faith. In "the fullness of time" (Gal 4:4), he sent his only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ the Saviour, who took flesh as an Asian! Exulting in the goodness of the continent's peoples, cultures, and religious vitality, and conscious at the same time of the unique gift of faith which she has received for the good of all, the Church in Asia cannot cease to proclaim: "Give thanks to the Lord for he is good, for his love endures for ever" (Ps 118:1). Because Jesus was born, lived, died and rose from the dead in the Holy Land, that small portion of Western Asia became a land of promise and hope for all mankind. -

Our Mother of Good Counsel Catholic Community

Our Mother of Good Counsel Catholic Community SERVED BY THE AUGUSTINIANS PASTOR: Fr. Alvin Paligutan, OSA ASSOCIATE PASTOR: Fr. Mark Menegatti, OSA In Residence: Fr. James Mott, OSA WEEKEND MASSES: RCIA & ADULT CONFIRMATION: BAPTISMS: WEEKDAY MASSES: QUINCEAÑERAS: CONFESSIONS: SAFEGUARD THE CHILDREN: RELIGIOUS EDUCATION CLASSES: CONFIRMATION CLASSES: 2060 N. Vermont Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90027 ~ (323) 664-2111 ~ www.omgcla.org School : 4622 Ambrose Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90027 ~ (323) 664-2131 ~ www.omgcschool.org I celebrate the Holy Father’s new DEL Celebro el nuevo Motu Proprio Motu Proprio Spiritus Domini Spiritus Domini del Santo Padre, where Pope Francis canonically donde el Papa Francisco abre opens the Ministry of Acolyte and canónicamente el Ministerio de Lector to Women. Rather than disregarding Acólita y Lectora a la Mujer. En lugar de ignorar the fact that women are already serving and el hecho de que las mujeres ya están sirviendo y reading, or suggesng that it has since been leyendo, o sugerir que desde entonces ha sido ilegı́timo, los laicos casi nunca se instalan en illegi mate, Lay persons are almost never installed into these Ministries of Lector and estos Ministerios de Lector y Acólito. Acolyte. ¿Cual es la diferencia? Esa es una What’s the difference? That is a pregunta que aún necesita relexión, y la queson that sll needs reflecon, and the implementación local deberá provenir de local implementaon will need to come from alguien más caliicado que yo. someone more qualified than I. Estas son algunas cosas que vale la pena These are a few things that are worth comprender para el contexto.