The Common Law: an Account of Its Reception in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law and Constitution

Commission on Justice in Wales: Supplementary evidence of the Welsh Government to the Commission on Justice in Wales Contents Law and the Constitution 1 History and evolution 1 Problems operating Part 4 of the Government of Wales Act from 2011 onwards 4 Draft Wales Bill (2015) 7 Wales Act 2017 9 Accessibility of the law in Wales (and England) 10 Government and Laws in Wales Bill 12 Implications of creating a Welsh legal jurisdiction 15 Conclusion 18 Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown copyright 2018 2 | Supplementary evidence of the WelshWG35635 Government Digital to ISBN the 978-1-78937-837-5 Commission on Justice in Wales Law and the Constitution 1. This paper is supplementary to the Welsh on designing a system of government that is the Government’s submission of 4 June 2018. most effective and produces the best outcomes for It focusses specifically on the law and the legal the people of Wales. Instead we have constitutional jurisdiction and its impact on government in Wales. arrangements which are often complex, confusing It also considers the potential impact of creating and incoherent. a Welsh legal jurisdiction and devolving the justice 5. One of the key junctures came in 2005 with system on the legal professions in Wales. the proposal to create what was to become a fully 2. The paper explores the incremental and fledged legislature for Wales. The advent of full piecemeal way in which Wales’ current system law making powers was a seminal moment and of devolved government has developed. -

THE RATIONAL STRENGTH of ENGLISH LAW AUSTRALIA the Law Book Co

THE RATIONAL STRENGTH OF ENGLISH LAW AUSTRALIA The Law Book Co. of Australasia Pty Ltd. Sydney : Melbourne : Brisbane CANADA AND U.S.A. The Carswell Company Limited Toronto INDIA N. M. Tripathi Limited Bombay NEW ZEALAND Legal Publications Ltd. Wellington THE HAMLYN LECTURES THIRD SERIES THE RATIONAL STRENGTH OF ENGLISH LAW BY F. H. LAWSON, D.c.L. of Gray's Inn, Barrister-at-Law, Professor of Comparative Law in the University of Oxford LONDON STEVENS & SONS LIMITED 1951 First published in 1951 by Stevens & Sons Limited of 119 <fe 120 Chancery IJine London - Law Publishers and printed in Great Britain by the Eastern Press Ltd. of London and Reading CONTENTS The Hamlyn Trust ..... page vii 1. SOURCES AND GENERAL CHARACTER OF THE LAW 3 2. CONTRACT ....... 41 3. PROPERTY 75 4. TORTS ........ 109 5. CONCLUSION ....... 143 HAMLYN LECTURERS 1949. The Right Hon. Sir Alfred Denning 1950. Richard O'Sullivan, K.C. 1951. F. H. Lawson, D.C.L. VI THE HAMLYN TRUST HE Hamlyn Trust came into existence under the will of the late Miss Emma Warburton THamlyn of Torquay, who died in 1941 aged 80. She came of an old and well-known Devon family. Her father, William Bussell Hamlyn, practised in Torquay as a solicitor for many years. She was a woman of dominant character, intelligent and cultured, well versed in literature, music, and art, and a lover of her country. She inherited a taste for law, and studied the subject. She travelled frequently on the Continent and about the Mediterranean and gathered impressions of comparative jurisprudence and ethnology. -

“English Law and Descent Into Complexity”

“ENGLISH LAW AND DESCENT INTO COMPLEXITY” GRAY’S INN READING BY LORD JUSTICE HADDON-CAVE Barnard’s Inn – 17th June 2021 ABSTRACT The Rule of Law requires that the law is simple, clear and accessible. Yet English law has in become increasingly more complex, unclear and inaccessible. As modern life becomes more complex and challenging, we should pause and reflect whether this increasingly complexity is the right direction and what it means for fairness and access to justice. This lecture examines the main areas of our legal system, legislation, procedure and judgments, and seeks to identify some of the causes of complexity and considers what scope there is for creating a better, simpler and brighter future for the law. Introduction 1. I am grateful to Gresham College for inviting me to give this year’s Gray’s Inn Reading.1 It is a privilege to follow a long line of distinguished speakers from our beloved Inn, most recently, Lord Carlisle QC who spoke last year on De-radicalisation – Illusion or Reality? 2. I would like to pay tribute to the work of Gresham College and in particular to the extraordinary resource that it makes available to us all in the form of 1,800 free public lectures available online stretching back nearly 40 years to Lord Scarman’s lecture Human Rights and the Democratic Process.2 For some of us who have not got out much recently, it has been a source of comfort and stimulation, in addition to trying to figure out the BBC series Line of Duty. 3. -

Welsh Tribal Law and Custom in the Middle Ages

THOMAS PETER ELLIS WELSH TRIBAL LAW AND CUSTOM IN THE MIDDLE AGES IN 2 VOLUMES VOLUME I1 CONTENTS VOLUME I1 p.1~~V. THE LAWOF CIVILOBLIGATIONS . I. The Formalities of Bargaining . .a . 11. The Subject-matter of Agreements . 111. Responsibility for Acts of Animals . IV. Miscellaneous Provisions . V. The Game Laws \TI. Co-tillage . PARTVI. THE LAWOF CRIMESAND TORTS. I. Introductory . 11. The Law of Punishtnent . 111. ' Saraad ' or Insult . 1V. ' Galanas ' or Homicide . V. Theft and Surreption . VI. Fire or Arson . VII. The Law of Accessories . VIII. Other Offences . IX. Prevention of Crime . PARTVIl. THE COURTSAND JUDICIARY . I. Introductory . 11. The Ecclesiastical Courts . 111. The Courts of the ' Maerdref ' and the ' Cymwd ' IV. The Royal Supreme Court . V. The Raith of Country . VI. Courts in Early English Law and in Roman Law VII. The Training and Remuneration of Judges . VIII. The Challenge of Judges . IX. Advocacy . vi CONTENTS PARTVIII. PRE-CURIALSURVIVALS . 237 I. The Law of Distress in Ireland . 239 11. The Law of Distress in Wales . 245 111. The Law of Distress in the Germanic and other Codes 257 IV. The Law of Boundaries . 260 PARTIX. THE L4w OF PROCEDURE. 267 I. The Enforcement of Jurisdiction . 269 11. The Law of Proof. Raith and Evideilce . , 301 111. The Law of Pleadings 339 IV. Judgement and Execution . 407 PARTX. PART V Appendices I to XI11 . 415 Glossary of Welsh Terms . 436 THE LAW OF CIVIL OBLIGATIONS THE FORMALITIES OF BARGAINING I. Ilztroductory. 8 I. The Welsh Law of bargaining, using the word bargain- ing in a wide sense to cover all transactions of a civil nature whereby one person entered into an undertaking with another, can be considered in two aspects, the one dealing with the form in which bargains were entered into, or to use the Welsh term, the ' bond of bargain ' forming the nexus between the parties to it, the other dealing with the nature of the bargain entered int0.l $2. -

Management and Land Disturbance Section of the City of Quincy Municipal Code Is Hereby

INTRODUCED BY: MAYOR THOMAS P. KOCH CITY OF QUINCY IN COUNCIL ORDER NO. 2021- 054 ORDERED: May 17, 2021 Upon recommendation of the Commissioner of Public Works, and with the approval of his Honor, the Mayor, the Chapter 300 Stormwater Management, Article II - Stormwater Management and Land Disturbance section of the City of Quincy Municipal Code is hereby amended by striking it in its entirety and inserting the attached provisions for: Chapter 300 Stormwater Management Article II Stormwater Management and Land Disturbance 300- 15. Findings and objectives. A. The harmful impacts of polluted and unmanaged stormwater runoff are known to cause: 1) Impairment of water quality and flow in lakes, ponds, streams, rivers, wetlands, and groundwater; 2) Contamination of drinking water supplies; 3) Erosion of stream channels; 4) Alteration or destruction of aquatic and wildlife habitat; 5) Flooding; and 6) Overloading or dogging of municipal storm drain systems. B. The objectives of this article are to: 1) Protect groundwater and surface water from degradation; 2) Require practices that reduce soil erosion and sedimentation and control the volume and rate of stormwater runoff resulting from development, construction, and land surface alteration; 3) Promote infiltration and the recharge of groundwater; 4) Prevent pollutants from entering the City of Quincy municipal separate storm sewer system ( MS4) and to minimize discharge of pollutants from the MS4; 5) Ensure adequate, long-term operation and maintenance of structural stormwater best management practices; 6) Ensure that soil erosion and sedimentation control measures and stormwater runoff control practices that are incorporated into the site planning and design processes are implemented and maintained; ORDER NO. -

English Contract Law: Your Word May Still Be Your Bond Oral Contracts Are Alive and Well – and Enforceable

Client Alert Litigation Client Alert Litigation March 13, 2014 English Contract Law: Your Word May Still be Your Bond Oral contracts are alive and well – and enforceable. By Raymond L. Sweigart American movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn is widely quoted as having said, ‘A verbal contract isn’t worth the paper it’s written on.’ He is also reputed to have stated, ‘I’m willing to admit that I may not always be right, but I am never wrong.’ With all due respect to Mr Goldwyn, he did not have this quite right and recent case law confirms he actually had it quite wrong. English law on oral contracts has remained essentially unchanged with a few exceptions for hundreds of years. Oral contracts most certainly exist, and they are certainly enforceable. Many who negotiate commercial contracts often assume that they are not bound unless and until the agreement is reduced to writing and signed by the parties. However, the courts in England are not at all reluctant to find that binding contracts have been made despite the lack of a final writing and signature. Indeed, as we have previously noted, even in the narrow area where written and signed contracts are required (for example pursuant to the Statute of Frauds requirement that contracts for the sale of land must be in writing), the courts can find the requisite writing and signature in an exchange of emails.1 As for oral contracts, a recent informative example is presented by the case of Rowena Williams (as executor of William Batters) v Gregory Jones (25 February 2014) reported on Lawtel reference LTL 7/3/2014 document number AC0140753. -

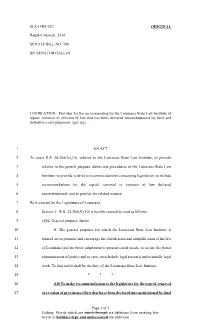

C:\TEMP\Copy of SB180 Original (Rev 0).Wpd

SLS 14RS-257 ORIGINAL Regular Session, 2014 SENATE BILL NO. 180 BY SENATOR GALLOT LEGISLATION. Provides for the recommending by the Louisiana State Law Institute of repeal, removal or revision of law that has been declared unconstitutional by final and definitive court judgment. (gov sig) 1 AN ACT 2 To enact R.S. 24:204(A)(10), relative to the Louisiana State Law Institute; to provide 3 relative to the general purpose, duties and procedures of the Louisiana State Law 4 Institute; to provide relative to recommendations concerning legislation; to include 5 recommendations for the repeal, removal or revision of law declared 6 unconstitutional; and to provide for related matters. 7 Be it enacted by the Legislature of Louisiana: 8 Section 1. R.S. 24:204(A)(10) is hereby enacted to read as follows: 9 §204. General purpose; duties 10 A. The general purposes for which the Louisiana State Law Institute is 11 formed are to promote and encourage the clarification and simplification of the law 12 of Louisiana and its better adaptation to present social needs; to secure the better 13 administration of justice and to carry on scholarly legal research and scientific legal 14 work. To that end it shall be the duty of the Louisiana State Law Institute: 15 * * * 16 (10) To make recommendations to the legislature for the repeal, removal 17 or revision of provisions of law that have been declared unconstitutional by final Page 1 of 3 Coding: Words which are struck through are deletions from existing law; words in boldface type and underscored are additions. -

2012 ANNUAL TOWN REPORT Bedford, Massachusetts

2012 ANNUAL TOWN REPORT Bedford, Massachusetts Town Organization Chart 3 Town Directory 4 Our Town 5 Town Administration 6 PART I REPORTS FROM COMMITTEES, DEPARTMENTS, & BOARDS Arbor Resource Committee 10 Bedford Housing Authority 11 Bedford Housing Partnership 13 Bicycle Advisory Committee 17 Board of Health 18 Board of Registrars of Voters 21 Cable Television Committee 23 Code Enforcement Department 25 Community Preservation Committee 27 Conservation Commission 28 Council on Aging 31 Department of Public Works 33 Depot Park Advisory Committee 37 Facilities Department 38 Fire Department 40 Historic District Commission 42 Historic Preservation Commission 43 Land Acquisition Committee 45 Patriotic Holiday Committee 46 Planning Board 47 Police Department 51 Public Library 55 Recreation Department 60 Selectmen 62 Town Center/Old Town Hall 64 Town Clerk 67 Town Historian 68 Volunteer Coordinating Committee 69 Youth & Family Services 70 Zoning Board of Appeals 75 2012 ANNUAL TOWN REPORT Bedford, Massachusetts PART II SCHOOLS Bedford Public Schools 77 Shawsheen Valley Regional Vocational/Technical School District 80 PART III ELECTIONS & TOWN MEETINGS Special Town Meeting November 7, 2011 86 2012 Town Caucus January 10, 2012 89 Presidential Primary Results March 10, 2012 92 Annual Town Election March 10, 2012 94 Annual Town Meeting March 26, 2012 95 Annual Town Meeting March 27, 2012 (Continued) 100 Annual Town Meeting April 2, 2012 (Continued) 114 PART IV FINANCE Board of Assessors 126 Finance Department 127 Collections 130 2011 Financial Report 131 Volunteer Opportunities and Questionnaire 155 Cover designed by Bedford resident Jean Hammond. Photograph of New Wilson Mill Dam by Town Engineer Adrienne St. John Painting of the Old Wilson Mill Dam by Edwin Graves Champney (c.1880s) courtesy of Bea Brown and the Bedford Historical Society 2012 Annual Report 3 www.bedfordma.gov 2012 Annual Report 4 www.bedfordma.gov TOWN OF BEDFORD DIRECTORY TOWN DEPARTMENTS & SERVICES Bedford Cable Access TV……………………………………….. -

The History and Operation of the Briggs Law of Massachusetts

THE HISTORY AND OPERATION OF THE BRIGGS LAW OF MASSACHUSETTS WINFRED OVERHO.SE* The problem of the mental capacity of persons accused of crime is one which has for several centuries been of considerable interest to the courts. Apparently prior to the middle of the eighteenth century, however, no great difficulty was experienced by the court in obtaining reliable evidence on this question-since at that time the experts were called in by the court as amici curiae. During the past two hundred years, however, the position of the experts has tended to develop into that of par- tisans,' and criticism has been widespread and caustic on the part not only of judges and lawyers but of the general public.2 By reason of the sensational nature of the crime charged in some cases where insanity is pleaded as a defense, undue attention has been focused by the public upon the r~le of the psychiatrist as an expert witness in criminal trials, despite the well recognized abuses of other types of expert testi- mony, criminal and civil alike. If criticism has been rampant, however, it cannot truthfully be said that no attempts have been made to improve the situation. Some of these attempts have partaken of the nature of action by professional societies, but the ones which concern us particularly are those which have been enacted into legislation. Of the types of legislative cures proposed, the most common has been that con- ferring upon the court the right or the duty, in certain specified cases, of appointing neutral experts. -

Mass.) (Appellate Brief) Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts

COMMONWEALTH, v. LIFE CARE CENTERS OF..., 2010 WL 3612917... 2010 WL 3612917 (Mass.) (Appellate Brief) Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. COMMONWEALTH, v. LIFE CARE CENTERS OF AMERICA, INC. No. SJC-10546. February 23, 2010. Appellant Life Care Centers of America, Inc.'s Reply Brief on Report of Questions of Law Pursuant to Mass. R. Crim. P. 34 By Counsel for the Defendant, Don Howarth (pro hav vice), Suzelle M. Smith (pro hac vice), Howarth & Smith, 523 West Sixth Street, Suite 728, Los Angeles, CA 90014, (213) 955-9400, R. Matthew Rickman (BBO # 637160), Alathea E. Porter (BBO # 661100), LibbyHoopes, P.C., 175 Federal Street, Suite 800, Boston, MA 02110, (617) 338-9300. *i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CASES AND AUTHORITIES ................................................................................................... ii I. Proper Application of the Doctrine of Respondeat Superior to a Criminal Case Is Not in Dispute ............ 1 A. Beneficial Finance Holds that Only if the Commonwealth Proves individual Employees Committed a 6 Crime Can the Corporate Employer Be Liable .............................................................................................. B. Merely Negligent Acts May not be Aggregated to Create a Crime ........................................................... 11 II. Proof Of Bad Purpose Is Required Under § 38 ......................................................................................... 13 III. Fairness Requires Prospective Application If The Court Adopts The Proposed Aggregation Doctrine -

Recent Cases

Missouri Law Review Volume 37 Issue 4 Fall 1972 Article 8 Fall 1972 Recent Cases Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Recent Cases, 37 MO. L. REV. (1972) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol37/iss4/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: Recent Cases Recent Cases CIVIL RIGHTS-TITLE VII OF CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964- DISMISSAL FROM EMPLOYMENT OF MINORITY-GROUP EMPLOYEE FOR EXCESSIVE WAGE GARNISHMENT Johnson v. Pike Corp. of America' Defendant corporation employed plaintiff, a black man, as a ware- houseman. Several times during his employment, plaintiff's wages were garnished to satisfy judgments. Defendant had a company rule stating, "Conduct your personal finances in such a way that garnishments will not be made on your wages," 2 and a policy of discharging employees whose wages were garnished in contravention of this rule. Pursuant to that policy, defendant dismissed plaintiff for violating the company rule. Plaintiff filed an action alleging that the practice causing his dismissal constituted discrimination against him because of race and, hence, violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Section 703 of Title VII provides: a. It shall be unlawful employment practice for an employer- 1. -

18-5924 Respondent BOM.Wpd

No. 18-5924 In the Supreme Court of the United States __________________ EVANGELISTO RAMOS, Petitioner, v. LOUISIANA, Respondent. __________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of Louisiana, Fourth Circuit __________________ BRIEF OF RESPONDENT __________________ JEFF LANDRY LEON A. CANNIZZARO. JR. Attorney General District Attorney, ELIZABETH B. MURRILL Parish of Orleans Solicitor General Donna Andrieu Counsel of Record Chief of Appeals MICHELLE GHETTI 619 S. White Street Deputy Solicitor General New Orleans, LA 70119 COLIN CLARK (504) 822-2414 Assistant Attorney General LOUISIANA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE WILLIAM S. CONSOVOY 1885 North Third Street JEFFREY M. HARRIS Baton Rouge, LA 70804 Consovoy McCarthy PLLC (225) 326-6766 1600 Wilson Blvd., Suite 700 [email protected] Arlington, VA 22209 Counsel for Respondent August 16, 2019 Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether this Court should overrule Apodaca v. Oregon, 406 U.S. 404 (1972), and hold that the Sixth Amendment, as incorporated through the Fourteenth Amendment, guarantees State criminal defendants the right to a unanimous jury verdict. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS QUESTION PRESENTED.................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................... iv STATEMENT............................... 1 A.Factual Background..................1 B.Procedural History...................2 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................. 4 ARGUMENT.............................. 11 I. THE SIXTH AMENDMENT’S JURY TRIAL CLAUSE DOES NOT REQUIRE UNANIMITY .......... 11 A. A “Trial By Jury” Under the Sixth Amendment Does Not Require Every Feature of the Common Law Jury......11 B. A Unanimous Verdict Is Not an Indispensable Component of a “Trial By Jury.”............................ 20 1. There is inadequate historical support for unanimity being indispensable to a jury trial......................