18-5924 Respondent BOM.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\TEMP\Copy of SB180 Original (Rev 0).Wpd

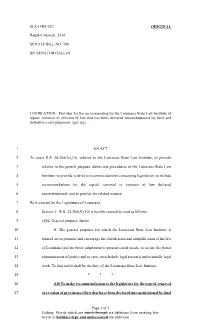

SLS 14RS-257 ORIGINAL Regular Session, 2014 SENATE BILL NO. 180 BY SENATOR GALLOT LEGISLATION. Provides for the recommending by the Louisiana State Law Institute of repeal, removal or revision of law that has been declared unconstitutional by final and definitive court judgment. (gov sig) 1 AN ACT 2 To enact R.S. 24:204(A)(10), relative to the Louisiana State Law Institute; to provide 3 relative to the general purpose, duties and procedures of the Louisiana State Law 4 Institute; to provide relative to recommendations concerning legislation; to include 5 recommendations for the repeal, removal or revision of law declared 6 unconstitutional; and to provide for related matters. 7 Be it enacted by the Legislature of Louisiana: 8 Section 1. R.S. 24:204(A)(10) is hereby enacted to read as follows: 9 §204. General purpose; duties 10 A. The general purposes for which the Louisiana State Law Institute is 11 formed are to promote and encourage the clarification and simplification of the law 12 of Louisiana and its better adaptation to present social needs; to secure the better 13 administration of justice and to carry on scholarly legal research and scientific legal 14 work. To that end it shall be the duty of the Louisiana State Law Institute: 15 * * * 16 (10) To make recommendations to the legislature for the repeal, removal 17 or revision of provisions of law that have been declared unconstitutional by final Page 1 of 3 Coding: Words which are struck through are deletions from existing law; words in boldface type and underscored are additions. -

Irish Constitutional Law

1 ERASMUS SUMMER SCHOOL MADRID 2011 IRISH CONSTITUTIONAL LAW Martin Kearns Barrister at Law Historical Introduction The Treaty of December 6, 1921 was the foundation stone of an independent Ireland under the terms of which the Irish Free State was granted the status of a self-governing dominion, like Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. Although the Constitution of the Ireland ushered in virtually total independence in the eyes of many it had been imposed by Britain through the Anglo Irish Treaty. 1 The Irish Constitution of 1922 was the first new Constitution following independence from Britain but by 1936 it had been purged of controversial symbols and external associations by the Fianna Faíl Government which had come to power in 1932.2 The Constitution of Ireland replaced the Constitution of the Irish Free State which had been in effect since the independence of the Free State from the United Kingdom on 6 December 1922. The motivation of the new Constitution was mainly to put an Irish stamp on the Constitution of the Free State whose institutions Fianna Faíl had boycotted up to 1926. 1 Signed in London on 6 December 1921. 2 e.g. under Article 17 every member of the Oireachtas had to take an oath of allegiance, swearing true faith and allegiance to the Constitution and fidelity to the Monarch; the representative of the King known as the Governor General etc. 2 Bunreacht na hÉireann an overview The official text of the constitution consists of a Preamble and fifty articles arranged under sixteen headings. Its overall length is approximately 16,000 words. -

Recent Cases

Missouri Law Review Volume 37 Issue 4 Fall 1972 Article 8 Fall 1972 Recent Cases Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Recent Cases, 37 MO. L. REV. (1972) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol37/iss4/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: Recent Cases Recent Cases CIVIL RIGHTS-TITLE VII OF CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964- DISMISSAL FROM EMPLOYMENT OF MINORITY-GROUP EMPLOYEE FOR EXCESSIVE WAGE GARNISHMENT Johnson v. Pike Corp. of America' Defendant corporation employed plaintiff, a black man, as a ware- houseman. Several times during his employment, plaintiff's wages were garnished to satisfy judgments. Defendant had a company rule stating, "Conduct your personal finances in such a way that garnishments will not be made on your wages," 2 and a policy of discharging employees whose wages were garnished in contravention of this rule. Pursuant to that policy, defendant dismissed plaintiff for violating the company rule. Plaintiff filed an action alleging that the practice causing his dismissal constituted discrimination against him because of race and, hence, violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Section 703 of Title VII provides: a. It shall be unlawful employment practice for an employer- 1. -

Supreme Court Visit to NUI Galway 4-6 March, 2019 Welcoming the Supreme Court to NUI Galway

Supreme Court Visit to NUI Galway 4-6 March, 2019 Welcoming the Supreme Court to NUI Galway 4-6 March, 2019 Table of Contents Welcome from the Head of School . 2 Te School of Law at NUI Galway . 4 Te Supreme Court of Ireland . 6 Te Judges of the Supreme Court . 8 2 Welcome from the Head of School We are greatly honoured to host the historic sittings of the Irish Supreme Court at NUI Galway this spring. Tis is the frst time that the Supreme Court will sit outside of a courthouse since the Four Courts reopened in 1932, the frst time the court sits in Galway, and only its third time to sit outside of Dublin. To mark the importance of this occasion, we are running a series of events on campus for the public and for our students. I would like to thank the Chief Justice and members of the Supreme Court for participating in these events and for giving their time so generously. Dr Charles O’Mahony, Head of School, NUI Galway We are particularly grateful for the Supreme Court’s willingness to engage with our students. As one of Ireland’s leading Law Schools, our key focus is on the development of both critical thinking and adaptability in our future legal professionals. Tis includes the ability to engage in depth with the new legal challenges arising from social change, and to analyse and apply the law to developing legal problems. Te Supreme Court’s participation in student seminars on a wide range of current legal issues is not only deeply exciting for our students, but ofers them an excellent opportunity to appreciate at frst hand the importance of rigorous legal analysis, and the balance between 3 necessary judicial creativity and maintaining the rule of law. -

The French Language in Louisiana Law and Legal Education: a Requiem, 57 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 57 | Number 4 Summer 1997 The rF ench Language in Louisiana Law and Legal Education: A Requiem Roger K. Ward Repository Citation Roger K. Ward, The French Language in Louisiana Law and Legal Education: A Requiem, 57 La. L. Rev. (1997) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol57/iss4/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT The French Language in Louisiana Law and Legal Education: A Requiem* I. INTRODUCTION Anyone familiar with the celebrated works of the sixteenth century French satirist Frangois Rabelais is sure to remember the protagonist Pantagruel's encounter with the Limousin scholar outside the gates of Orldans.1 During his peregrinations, the errant Pantagruel happens upon the Limousin student who, in response to a simple inquiry, employs a gallicized form of Latin in order to show off how much he has learned at the university.? The melange of French and Latin is virtually incomprehensible to Pantagruel, prompting him to exclaim, "What the devil kind of language is this?"' 3 Determined to understand the student, Pantagruel launches into a series of straightforward and easily answerable questions. The Limousin scholar, however, responds to each question using the same unintelligi- ble, bastardized form of Latin." The pretentious use of pseudo-Latin in lieu of the French vernacular infuriates Pantagruel and causes him to physically assault the student. -

The Bulletin

NUMBER 55 WINTER 2007 THE BULLETIN 56th ANNUAL MEETING A RESOUNDING SUCCESS First to London 9/14-17 then Dublin 9/17-20, 2006 F rom in Dublin, the spirited Republic of musical greeting Ireland. It has of a uniformed band become a tradition of welcoming them to stately the College periodically to Kensington Palace, the former home return to London, to the roots of of Diana, Princess of Wales, to an impromptu a the legal profession in the common law world, and capella rendition of Danny Boy by a Nobel Laureate to visit another country in Europe afterwards. at the end of the last evening in Dublin Castle, the 56th Annual Meeting of the American College of Trial The Board of Regents, including the past presidents, Lawyers in London and the follow-up conference in meeting in advance of the Fellows’ London meeting, Dublin were memorable events. had represented the United States at an evensong service at Westminster Abbey, commemorating the More than 1,200 Fellows and their spouses attended fifth anniversary of 9/11. After the service, President the London meeting, the fifth the College has held Michael A. Cooper laid a wreath on the memorial in that city and the first since 1998. And 510 of to The Innocent Victims, located in the courtyard them continued to the College’s first ever meeting outside the West Door of the Abbey. The Regents LONDON-DUBLIN, con’t on page 37 This Issue: 88 PAGES Profile: SYLVIA WALBOLT p. 17 NOTABLE QUOTE FROM the LONDON-DUBLIN MEETING ““Let us pray. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit Fifth Circuit FILED July 6, 2021

Case: 20-30422 Document: 00515926578 Page: 1 Date Filed: 07/06/2021 United States Court of Appeals United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit Fifth Circuit FILED July 6, 2021 No. 20-30422 Lyle W. Cayce Clerk Walter G. Goodrich, in his capacity as the Independent Executor on behalf of Henry Goodrich Succession; Walter G. Goodrich; Henry Goodrich, Jr.; Laura Goodrich Watts, Plaintiffs—Appellants, versus United States of America, Defendant—Appellee. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Louisiana USDC No. 5:17-CV-610 Before Higginbotham, Stewart, and Wilson, Circuit Judges. Carl E. Stewart, Circuit Judge: Plaintiffs-Appellants Walter G. “Gil” Goodrich (individually and in his capacity as the executor of his father—Henry Goodrich, Sr.’s— succession), Henry Goodrich, Jr., and Laura Goodrich Watts brought suit against Defendant-Appellee United States of America. Henry Jr. and Laura are also Henry Sr.’s children. Plaintiffs claimed that, in an effort to discharge Henry Sr.’s tax liability, the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) has Case: 20-30422 Document: 00515926578 Page: 2 Date Filed: 07/06/2021 No. 20-30422 wrongfully levied their property, which they had inherited from their deceased mother, Tonia Goodrich, subject to Henry Sr.’s usufruct. Among other holdings not relevant to the disposition of this appeal, the magistrate judge1 determined that Plaintiffs were not the owners of money seized by the IRS and that represented the value of certain liquidated securities. This appeal followed. Whether Plaintiffs are in fact owners of the disputed funds is an issue governed by Louisiana law. -

Techniques of Judicial Interpretation in Louisiana Albert Tate Jr

Louisiana Law Review Volume 22 | Number 4 Symposium: Louisiana and the Civil Law June 1962 Techniques of Judicial Interpretation in Louisiana Albert Tate Jr. Repository Citation Albert Tate Jr., Techniques of Judicial Interpretation in Louisiana, 22 La. L. Rev. (1962) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol22/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Techniques of Judicial Interpretation in Louisiana Albert Tate, Jr.* It is sometimes stated that, in deciding legal disputes, a judge merely finds the correct law and applies it to the facts of the case in controversy. It is my intention to discuss here some of the techniques available to a Louisiana judge to "find the law" by which to decide the case, once the facts are estab- lished. We must, preliminarily, make brief mention of the legal system under which a Louisiana judge works. Although this has been disputed in modern times,' scholars now generally agree that Louisiana is still a civil law jurisdiction, but with substantial infusions of common law concepts and techniques.2 For present purposes, what this essentially means is that the primary basis of law for a civilian is legislation, and not (as in the common law) a great body of tradition in the form of prior decisions of the courts.3 In important respects, the statutory *Judge, Court of Appeal, Third Circuit. -

The Filtering of Appeals to the Supreme Courts

NETWORK OF THE PRESIDENTS OF THE SUPREME JUDICIAL COURTS OF THE EUROPEAN UNION Dublin Conference November 26-27, 2015 Farmleigh House Farmleigh Castleknock, Dublin 15, Ireland INTRODUCTORY REPORT The Filtering of Appeals to the Supreme Courts Rimvydas Norkus President of the Supreme Court of Lithuania Colloquium organised with the support of the European Commission Colloque organisé avec le soutien de la Commission européenne I. Introduction. On the Nature of Appeal to Supreme Court Part VIII of the Constitution of 3rd May 1791 of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the first constitution of its type in Europe, stated that the judicial authority shall not be carried out either by the legislative authority or by the King, but by magistracies instituted and elected to that end. The Constitution also mentioned appellate courts and the Supreme Court. The Constitution did not address in any way filtering of appeals. However, even long before the Constitution of 1791 was adopted, the Third Statute of Grand Duchy of Lithuania, approved in 1588, forbid to appeal intermediate decisions of lower courts to the Supreme Tribunal of the Grand Duchy. Later laws of the Grand Duchy have even established a fine for not complying with this provision. Thus the necessity to limit a right of application to Supreme Court was understood and recognized by a legal system of Lithuania long ago. Historical sources and researches reveal to us now that one of the main reasons why this was done was in fact huge workload of a superior court and delay that was not uncommon in those times. It could take ten or more years to decide some cases before the Supreme Tribunal of the Grand Duchy. -

The History and Development of the Louisiana Civil Code, 19 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 19 | Number 1 Legislative Symposium: The 1958 Regular Session December 1958 The iH story and Development of the Louisiana Civil Code John T. Hood Jr. Repository Citation John T. Hood Jr., The History and Development of the Louisiana Civil Code, 19 La. L. Rev. (1958) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol19/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The History and Development of the Louisiana Civil Code* John T. Hood, Jr.t The Louisiana Civil Code has been called the most perfect child of the civil law. It has been praised as "the clearest, full- est, the most philosophical, and the best adapted to the exigencies of modern society." It has been characterized as "perhaps the best of all modern codes throughout the world." Based on Roman law, modeled after the great Code Napoleon, enriched with the experiences of at least twenty-seven centuries, and mellowed by American principles and traditions, it is a living and durable monument to those who created it. After 150 years of trial, the Civil Code of Louisiana remains venerable, a body of substantive law adequate for the present and capable of expanding to meet future needs. At this Sesquicentennial it is appropriate for us to review the history and development of the Louisiana Civil Code. -

Louisiana and Texas Oil & Gas Law: an Overview of the Differences

Louisiana Law Review Volume 52 | Number 4 March 1992 Louisiana and Texas Oil & Gas Law: An Overview of the Differences Patrick H. Martin Louisiana State University Law Center J. Lanier Yeates Repository Citation Patrick H. Martin and J. Lanier Yeates, Louisiana and Texas Oil & Gas Law: An Overview of the Differences, 52 La. L. Rev. (1992) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol52/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Louisiana and Texas Oil & Gas Law: An Overview of the Differences* Patrick H. Martin** and J. Lanier Yeates*** I. INTRODUCTION-SCOPE OF ARTICLE There is more that separates Louisiana and Texas than the Sabine River. Our two states have followed different paths to the law, as is soon discovered by any attorney who attempts to practice across state lines. Such attorneys find they must confront new terminology. Louisiana lawyers new to Texas may think a remainder is an after-Christmas sales item at Neiman-Marcus. A Texas lawyer, when faced with reference to a naked owner in Louisiana law, perhaps will conjure up the sort of legal practice that William Hurt had in drafting a will for Kathleen Turner in Body Heat. The terms apply to types of interest which are virtually the same. Our purpose in this presentation is to highlight certain features of the legal systems of the two states that make them distinct from one another, and also to go over certain areas in which they are not terribly different. -

Louisiana Conflicts Law: Two "Surprises" Symeon C

Louisiana Law Review Volume 54 | Number 3 January 1994 Louisiana Conflicts Law: Two "Surprises" Symeon C. Symeonides Repository Citation Symeon C. Symeonides, Louisiana Conflicts Law: Two "Surprises", 54 La. L. Rev. (1994) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol54/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Louisiana Conflicts Law: Two "Surprises" Symeon C. Symeonides" TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Surprise # 1: Louisiana Has Always Had Choice-of-Law Legislation . ........................................ 497 II. Surprise # 2: Louisiana Has a New Comprehensive Law on Choice of Law ..................................... 502 A. The New Law .................................. 502 B. Cases Decided Under the New Law ................... 505 1. Tort Conflicts ............................... 505 a. Issues of Loss Distribution .................... 505 b. Issues of Conduct and Safety .................. 513 c. Products Liability and Punitive Damages .......... 517 2. Contract Conflicts ............................. 522 3. Workers' Compensation Conflicts .................. 527 4. Liberative Prescription Conflicts ................... 530 a. The Old Law ............................. 531 b. Lessons Derived from Experience and Comparison ... 537 c. The New Law ............................ 539 i. The New Basic Rule ..................... 539 ii. The First Exception: Actions Barred by the Lex Fori but not by the Lex Causae .......... 540 iii. The Second Exception: Actions Barred by the Lex Causae but not by the Lex Fori .......... 545 C. Some Interim Conclusions .......................... 548 I. SURPRISE # 1: LOUISIANA HAS ALWAYS HAD CHOICE-OF-LAW LEGISLATION The above statement is, of course, not new.