Chapter 6: Infrastructure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report on Traffic National Waterways: Fy 2020-21

ANNUAL REPORT ON TRAFFIC NATIONAL WATERWAYS: FY 2020-21 INLAND WATERWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA MINISTRY OF PORTS, SHIPPING & WATERWAYS A-13, SECTOR-1, NOIDA- 201301 WWW.IWAI.NIC.IN Inland Waterways Authority of India Annual Report 1 MESSAGE FROM CHAIRPERSON’S DESK Inland Water Transport is (IWT) one of the important infrastructures of the country. Under the visionary leadership of Hon’ble Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi, Inland Water Transport is gaining momentum and a number of initiatives have been taken to give an impetus to this sector. IWAI received tremendous support from Hon’ble Minister for Ports, Shipping & Waterways, Shri Mansukh Mandaviya, to augment its activities. The Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) under Ministry of Ports, Shipping & Waterways, came into existence on 27th October 1986 for development and regulation of inland waterways for shipping and navigation. The Authority primarily undertakes projects for development and maintenance of IWT infrastructure on National Waterways. To boost the use of Inland Water Transport in the country, Hon’ble Prime Minister have launched Jibondhara–Brahmaputra on 18th February, 2021 under which Ro-Ro service at various locations on NW-2 commenced, Foundation stone for IWT terminal at Jogighopa was laid and e-Portals (Car-D and PANI) for Ease-of-Doing-Business were launched. The Car-D and PANI portals are beneficial to stakeholders to have access to real time data of cargo movement on National Waterways and information on Least Available Depth (LAD) and other facilities available on Waterways. To promote the Inland Water Transport, IWAI has also signed 15 MoUs with various agencies during the launch of Maritime India Summit, 2021. -

Pre-Feasibility for Proposed MMLP at Jogighopa

PrePre--Feasibilityfeasibility forReport for ProposedProposed MMLPInter- Modalat Terminal at Jogighopa Jogighopa(DRAFT) FINAL REPORT January 2018 April 2008 A Newsletter from Ernst & Young Contents Executive Summary ......................... 7 Introduction .................................... 9 1 Market Analysis ..................... 11 1.1 Overview of North-East Cargo Market ................................................................................... 11 1.2 Potential for Waterways ............................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.3 Potential for MMLP at Jogighopa .......................................................................................... 16 2 Infrastructure Assessment ..... 19 2.1 Warehousing Area Requirement ........................................................................................... 19 2.2 Facility Area Requirement .................................................................................................... 20 2.3 Handling Equipments ........................................................................................................... 20 3 Financial Assessment ............. 23 3.1 Capital Cost Estimates ......................................................................................................... 23 3.2 Operating Cost Estimates .................................................................................................... 24 3.3 Revenue Estimates ............................................................................................................. -

Brahmaputra and the Socio-Economic Life of People of Assam

Brahmaputra and the Socio-Economic Life of People of Assam Authors Dr. Purusottam Nayak Professor of Economics North-Eastern Hill University Shillong, Meghalaya, PIN – 793 022 Email: [email protected] Phone: +91-9436111308 & Dr. Bhagirathi Panda Professor of Economics North-Eastern Hill University Shillong, Meghalaya, PIN – 793 022 Email: [email protected] Phone: +91-9436117613 CONTENTS 1. Introduction and the Need for the Study 1.1 Objectives of the Study 1.2 Methodology and Data Sources 2. Assam and Its Economy 2.1 Socio-Demographic Features 2.2 Economic Features 3. The River Brahmaputra 4. Literature Review 5. Findings Based on Secondary Data 5.1 Positive Impact on Livelihood 5.2 Positive Impact on Infrastructure 5.2.1 Water Transport 5.2.2 Power 5.3 Tourism 5.4 Fishery 5.5 Negative Impact on Livelihood and Infrastructure 5.6 The Economy of Char Areas 5.6.1 Demographic Profile of Char Areas 5.6.2 Vicious Circle of Poverty in Char Areas 6. Micro Situation through Case Studies of Regions and Individuals 6.1 Majuli 6.1.1 A Case Study of Majuli River Island 6.1.2 Individual Case Studies in Majuli 6.1.3 Lessons from the Cases from Majuli 6.1.4 Economics of Ferry Business in Majuli Ghats 6.2 Dhubri 6.2.1 A Case Study of Dhubri 6.2.2 Individual Case Studies in Dhubri 6.2.3 Lessons from the Cases in Dhubri 6.3 Guwahati 6.3.1 A Case of Rani Chapari Island 6.3.2 Individual Case Study in Bhattapara 7. -

A Series of Measures Taken by the Indian Government Has Enabled A

Seamless connectivity www.worldcommercereview.com A series of measures taken by the Indian government has enabled a seamless connectivity through inland water transport among BBIN countries. Bipul Chatterjee and Veena Vidyadharan consider the effects on the region roviding a much-required boost to the inland water transport sector in India, the world’s largest shipping firm, Maersk moved 16 containers along National Waterway 1 from Varanasi (Uttar Pradesh) to Kolkata (West Bengal) recently in February, 2019. As container cargo transport through waterways reduces logistics cost and allows easier modal shift, this is expected to be a major leap in redefining the transport narrative for not Pjust India but also for its neighbouring countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal. A series of measures has been taken by the Government of India in the past few years to improve the logistics infrastructure in the country. This includes setting up of logistics parks, multimodal terminals, Sagarmala Project1, e-mobility solutions and infrastructural development of rail, road and waterways. Despite these initiatives, India’s rank dropped from 35th to 44 in the recently published World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index (2018). Similar decline was observed in the case of Nepal (144) Bangladesh (100) and Bhutan (149) compared to previous data of 2016. Though the fruitfulness of the reform measures will take time to realise, it is to be mentioned that the thrust to develop inland waterways for trade and transport got intensified lately after the declaration of National Waterways Act in 2016. The National Waterway-1 from Allahabad to Haldia in the Ganga- Bhagirathi-Hooghly river system and National Waterway-2 from Sadiya to Dhubri in the Brahmaputra river are the two important waterways that are projected to play a vital role in improving the inland water transport connectivity of India with its eastern www.worldcommercereview.com neighbours. -

Conservation of Gangetic Dolphin in Brahmaputra River System, India

CONSERVATION OF GANGETIC DOLPHIN IN BRAHMAPUTRA RIVER SYSTEM, INDIA Final Technical Report A. Wakid Project Leader, Gangetic Dolphin Conservation Project Assam, India Email: [email protected] 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT There was no comprehensive data on the conservation status of Gangetic dolphin in Brahmaputra river system for last 12 years. Therefore, it was very important to undertake a detail study on the species from the conservation point of view in the entire river system within Assam, based on which site and factor specific conservation actions would be worthwhile. However, getting the sponsorship to conduct this task in a huge geographical area of about 56,000 sq. km. itself was a great problem. The support from the BP Conservation Programme (BPCP) and the Rufford Small Grant for Nature Conservation (RSG) made it possible for me. I am hereby expressing my sincere thanks to both of these Funding Agencies for their great support to save this endangered species. Besides their enormous workload, Marianne Dunn, Dalgen Robyn, Kate Stoke and Jaimye Bartake of BPCP spent a lot of time for my Project and for me through advise, network and capacity building, which helped me in successful completion of this project. I am very much grateful to all of them. Josh Cole, the Programme Manager of RSG encouraged me through his visit to my field area in April, 2005. I am thankful to him for this encouragement. Simon Mickleburgh and Dr. Martin Fisher (Flora & Fauna International), Rosey Travellan (Tropical Biology Association), Gill Braulik (IUCN), Brian Smith (IUCN), Rundall Reeves (IUCN), Dr. A. R. Rahmani (BNHS), Prof. -

Expanding Tradable Benefits of Inland Waterways Case of India

Expanding Tradable Benefits of Inland Waterways Case of India Published By D-217, Bhaskar Marg, Bani Park, Jaipur 302016, India Tel: +91.141.2282821, Fax: +91.141.2282485 Email: [email protected], Web site: www.cuts-international.org With the support of © CUTS International, 2017 First published: December 2017 This document has been produced by CUTS International Printed in India by M S Printer, Jaipur This document is the output of the study designed and implemented by CUTS International and its strategic partners – Royal Society for Protection of Nature (RSPN), South Asia Watch on Trade, Economics and Environment (SAWTEE) and Unnayan Shamannay which contributes to the project ‘Expanding tradable benefits of trans-boundary water: Promoting navigational usage of inland waterways in Ganga and Brahmaputra basins’. More details are available at: www.cuts- citee.org/IW/ This publication is made possible with the support of The Asia Foundation. The views and opinions expressed in this publication is that of CUTS International and partners and not of The Asia Foundation. #1715 2 Contents Acknowledgement...................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................ 6 Contributors .............................................................................................................. 7 Executive Summary................................................................................................... -

Chapter 3 Assam

Chapter 3 Assam Udayon Misra 1. The Ahom Period (1328-1826) The impression has long sought to be created that the “North-East” is a landlocked area and that its geographical isolation is a major factor contributing to its economic backwardness. Not to speak of the pre-Ahom period when Assam, made up primarily of the Brahmaputra Valley, had quite an active interaction with the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, even under the Ahom rulers (1328-1826) who were known for their closed-door approach, there was active trade between Assam and her western neighbours, Bengal and Bihar as also with Bhutan, Tibet and Myanmar. Describing the kingdom of Assam during the height of Ahom rule in the seventeenth century, the historian S.K.Bhuyan states: “The kingdom of Assam, as it was constituted during the last 140 years of Ahom rule, was bounded on the north by a range of mountains inhabited by the Bhutanese, Akas, Daflas and Abors; on the east, by another line of hills people by the Mishmis and the Singhphos; on the south, by the Garo, Khasi, Naga and Patkai hills; on the west, by the Manas or Manaha river on the north bank, and the Habraghat Pargannah on the south in the Bengal district of Rungpore. The kingdom where it entered from Bengal commenced with the Assam Choky (gate) on the north bank of the Brahmaputra, opposite Goalpara; while on the south bank it commenced from the Nagarberra hill at a distance of 21 miles to the east of Goalpara. “The kingdom was about 500 miles in length, with an average breadth of 60 miles. -

IRBM for Brahmaputra Sub-Basin Water Governance, Environmental Security and Human Well-Being

IRBM for Brahmaputra Sub-basin Water Governance, Environmental Security and Human Well-being Jayanta Bandyopadhyay Nilanjan Ghosh Chandan Mahanta IRBM for Brahmaputra Sub-basin Water Governance, Environmental Security and Human Well-being Jayanta Bandyopadhyay Nilanjan Ghosh Chandan Mahanta i Observer Research Foundation 20, Rouse Avenue Institutional Area, New Delhi - 110 002, INDIA Ph. : +91-11-43520020, 30220020 Fax : +91-11-43520003, 23210773 E-mail: [email protected] ©2016 Copyright: Observer Research Foundation ISBN: 978-81-86818-22-0 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder (s) and/or the publisher. Typeset by Vinset Advt., Delhi Printed and bound in India Cover: Vaibhav Todi via Flickr. ii IRBM for Brahmaputra Sub-basin: Water Governance, Environmental Security and Human Well-being Table of Contents About the Authors v Acknowledgements vi Foreword vii Preface ix I The Brahmaputra River Sub-basin 1 II Integrated Management of Trans-boundary Water Regimes: A Conceptual Framework in the Context of Brahmaputra Sub-basin 19 III The Brahmaputra Sub-basin in the DPSIR Framework 43 IV Management Challenges Facing Human Well-being and Environmental Security in the Brahmaputra Sub-basin 49 V Institutional Response: A Regional Organisation for the Lower Brahmaputra Sub-basin 61 References 73 iii IRBM for Brahmaputra Sub-basin: Water Governance, Environmental Security and Human Well-being About the Authors Jayanta Bandyopadhyay is a retired Professor from IIM Calcutta. He obtained his PhD in Engineering from IIT Kanpur, and after completing his doctoral work, shifted his research interests to the Himalaya and, in particular, the challenges in sustaining the region's rivers. -

Assam Development Report

The Core Committee (Composition as in 2002) Dr. K. Venkatasubramanian Member, Planning Commission Chairman Shri S.C. Das Commissioner (P&D), Government of Assam Member Prof Kirit S. Parikh Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research Member Dr. Rajan Katoch Adviser (SP-NE), Planning Commission Member-Convener Ms. Somi Tandon for the Planning Commission and Shri H.S. Das & Dr. Surojit Mitra from the Government of Assam served as members of the Core Committee for various periods during 2000-2002. Project Team Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai Professor Kirit S. Parikh (Leader and Editor) Professor P. V. Srinivasan Professor Shikha Jha Professor Manoj Panda Dr. A. Ganesh Kumar Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research, New Delhi Shri Sanjoy Hazarika Shri Biswajeet Saikia Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development, Guwahati Dr. B. Sarmah Dr. Kalyan Das Professor Abu Nasar Saied Ahmed Indian Statistical Institute, New Delhi Professor Atul Sarma Acknowledgements We thank Planning Commission and the Government of Assam for entrusting the task to prepare this report to Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR). We are particularly indebted to Dr. K. Venkatasubramanian, Member, Planning Commission and Chairman of the Core Committee overseeing the preparation of the Report for his personal interest in this project and encouragement and many constructive suggestions. We are extremely grateful to Dr. Raj an Katoch of the Planning Commission for his useful advice, overall guidance and active coordination of the project, which has enabled us to bring this exercise to fruition. We also thank Ms. Somi Tandon, who helped initiate the preparation of the Report, all the members of the Core Committee and officers of the State Plans Division of the Planning Commission for their support from time to time. -

Inland Waterways

Development of Logistics Infrastructure: Inland Waterways 22nd November 2019 Inland Waterways Authority of India Ministry of Shipping, Govt. of India1 IWAI - Overview 111 NWs with total navigable length of ~20,000 km Establishment of Inland Waterways Authority of India 1986* Ganga, Bhagirathi, Brahmaputra Hooghly river system NW-2 Declaration of 5 National 1986 NW-1 to Waterways (NWs) YEAR 2014 NW-1 to NW-5 NW-5 Mahanadi, Brahmani & East coast canal 2014 NW-4 Declaration of 106 new National Godavari, Krishna rivers and onwards Waterways under the National Kakinada-Puducherry Canal Waterways Act, 2016 West Coast Canal, NW-3 * Pre-1986: Sector was under IWT Directorate Udyogmandal & (Ministry of Surface Transport) Champakara Canals *Map not to scale 2 Traffic on NWs TrafficReadiness on NWs of IWAI 14 operational NWs; ~72 million tonne traffic (FY18-19) Cargo traffic on National Waterways (million tonnes) Share of commodities transported on National waterways (in %) 72.31 Sundarbans, 3.23 Flyash 55.01 Steel Gujarat waterways, 5% 4% Gujarat waterways, 28.82 Limestone Others coal & coke 11.52 5% 14% 30% Maharashtra Maharashtra waterways, 25.96 Construction waterways, 28.34 Iron ore material 38% 4% Goa waterways, NW-4, 0.45 11.09 NW-3, 0.4 Goa waterways, 3.76 NW-3, 0.41 NW-2, 0.56 NW-2, 0.50 NW-1, 5.48 NW-1, 6.79 FY 2017 - 18 FY2018 - 19 . Predominantly bulk commodities such as Iron ore, Coal, *NW-4 not operational during FY 2017-18 Limestone, Fly ash currently use IWT mode 3 National Waterway-1: Jal Marg Vikas Project Jal Marg Vikas Project -

Inland Water Transport in NER By

Presentation on Inland Water Transport in NER By Inland Waterways Authority of India (Ministry of Shipping, Road Transport & Highways) Guwahati, the 9th March 2007 SADIYA Subansiri Hydel project SAIKHOWA Digboi refinery JAMGURI DIBRUGARH BOGIBIL TEJPUR Bongaigon refinery NEAMATI Numaligarh refinery JOGIGHOPA SILGHAT Legend Guwahati refinery DHUBRI Declared waterway (SHISHUMARA) PANDU BANGLADESH River distance B.Border (Dhubri) – Guwahati 260 km BANGLADESH Guwahati - Dibrugarh 508 km Dibrugarh– Sadiya 123 km Total length 891 km 1 North Bank South Bank Subanasiri Noa dihang Burali Burhi dihang Bargang Disang SADIYA Dhansiri Dikhu Puthimari Jhanju SAIKHOWA Pagladiya Dhansiri DIBRUGARH Beki Kopili Manas Kulsi BOGIBIL Aie Krishnai JAMGURI Champamati Jinary Gadadhar TEJPUR SILGHAT R. RA PUT HMA JOGIGHOPA BRA GUWAHATI DHUBRI PANDU H B A N G L A D SHISHUMARA E S Barak Valley Bhanga Badarpur Silchar 2 Objective Freight transportation by IWT to rise from the present level of 0.03 btkm to 5 btkm by 2025 Importance of IWT for NER z IWT offers shorter route compared to Road/rail z IWT operational even during flood season z Best suited for bulk commodities & Project cargo/ODC- z Provides best and low cost connectivity to hinterland z Employment potential enormous (NCAER Study Feb 2006) every km of IWT operation generates about 3000 jobs 1 lakh investment in IWT results in 6.5 manyears while in rail 0.58 and in other modes 0.87 manyears 3 Importance of IWT for NER Therefore, z Development of IWT mode in NER a strategic & economic imperative z Need for an investment & development strategy z Also need for increasing the efficiency of IWT mode. -

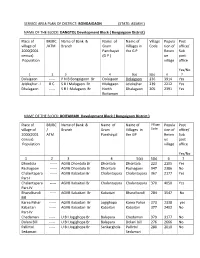

Service Area Plan of District: Bongaigaon (State: Assam )

SERVICE AREA PLAN OF DISTRICT: BONGAIGAON (STATE: ASSAM ) NAME OF THE BLOCK: DANGTOL Development Block ( Bongaigaon District) Place of BR/BC Name of Bank & Name of Name of Village Popula Post village of /ATM Branch Gram Villages in Code tion of office/ 2000(2001 Panchayat the G P Reven Sub census) (G P ) ue post Population village office Yes/No 1 2 3 4 5(a) 5(b) 6 7 Dolaigaon ‐‐‐‐‐ P N B Bongaigaon Br Dolaigaon Dolaigaon 236 3914 Yes Jelekajhar ‐ I B C S B I Mulagaon Br Mulagaon Jelekajhar 239 2212 Yes Dhalagaon ‐‐‐‐‐ S B I Mulagaon Br North Dhalagaon 205 2391 Yes Boitamari NAME OF THE BLOCK: BOITAMARI Development Block ( Bongaigaon District ) Place of BR/BC Name of Bank & Name of Name of Village Popula Post village of / Branch Gram Villages in Code tion of office/ 2000(2001 ATM Panchayat the GP Reven Sub census) ue post Population village office Yes/No 1 2 3 4 5(a) 5(b) 6 7 Dhontola ‐‐‐‐‐‐ AGVB Dhontola Br Dhontola Dhontola 223 2105 Yes Pachagaon ‐‐‐‐‐‐ AGVB Dhontola Br Dhontola Pachagaon 947 2386 No Chalantapara ‐‐‐‐‐‐ AGVB Kabaitari Br Chalantapara Chalantapara 367 2177 Yes Part‐I Chalantapara ‐‐‐‐‐ AGVB Kabaitari Br Chalantapara Chalantapara 370 4050 Yes Part‐IV Bharalkundi ‐‐‐‐‐ AGVB Kabaitari Br Kabaitari Bharalkundi 284 3547 No Bill Karea Pahar ‐‐‐‐‐‐ AGVB Kabaitari Br Jogighopa Karea Pahar 373 2338 yes Kabaitari ‐‐‐‐‐‐ AGVB Kabaitari Br Kabaitari Kabaitari 377 2402 No Part‐IV Chedamari ‐‐‐‐‐ U B I Jogighopa Br Balapara Chedamari 379 3177 No Dolani Bill ‐‐‐‐‐ U B I Jogighopa Br Balapara Dolani bill 276 2666 No Pallirtul ‐‐‐‐‐ U