Chapter 3 Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Abikal Borah 2015

Copyright By Abikal Borah 2015 The Report committee for Abikal Borah certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) Supervisor: ________________________________________ Mark Metzler ________________________________________ James M. Vaughn A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M. Phil Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2015 A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M.A. University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Mark Metzler Abstract: This essay considers the history of two commodities, tea in Georgian England and opium in imperial China, with the objective of explaining the connected histories in the Eurasian landmass. It suggests that an exploration of connected histories in the Eurasian landmass can adequately explain the process of integration of southeastern sub-Himalayan region into the global capitalist economy. In doing so, it also brings the historiography of so called “South Asia” and “East Asia” into a dialogue and opens a way to interrogate the narrow historiographical visions produced from area studies lenses. Furthermore, the essay revisits a debate in South Asian historiography that was primarily intended to reject Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory. While explaining the historical differences of southeastern sub-Himalayan region with peninsular India, Bengal, and northern India, this essay problematizes the South Asianists’ critiques of Wallerstein’s conceptual model. -

DISTRICTWISE LIST of AFFILIATED COLLEGES/INSTITUTES UNDER DIBRUGARH UNIVERSITY (NAAC Accreditated)

DISTRICTWISE LIST OF AFFILIATED COLLEGES/INSTITUTES UNDER DIBRUGARH UNIVERSITY (NAAC Accreditated) TINSUKIA DISTRICT NAAC Accreditation Status Sl. COLLEGE NAME & Year of STATUS st nd No ADDRESS Establishment 1 Cycle 2 Cycle Grade CGPA 1 Digboi College Permanent 1965 B+ B 2.47 P.O. Digboi, Dist. Tinsukia Affiliation (15/11/2015) Pin 786171 (Assam) 2 Digboi Mahila Permanent 1981 C++ Mahavidyalaya Affiliation Muliabari , P.O. Digboi Dist. Tinsukia Pin 786171(Assam) 3 Doomdooma College Permanent 1967 B B P.O. Rupai Saiding, Affiliation (16/09/2011) Dist. Tinsukia, Pin 786153 (Assam) 4 Margherita College Permanent 1978 B B P.O. Margherita Affiliation (1/5/2015) Dist. Tinsukia, Pin 786181 (Assam) 5 Sadiya College Permanent 1982 C+ P.O. Chapakhowa Affiliation Dist. Tinsukia, Pin 786157 (Assam) 6 Tinsukia College Permanent 1956 B B+ 2.55 P.O. Tinsukia, Affiliation (15/9/2016) Dist. Tinsukia, Pin 786125 (Assam) 7 Tinsukia Commerce Permanent 1972 B B 2.10 College Affiliation (3/5/2017) P.O. Sripuria Dist. Tinsukia Pin 786145(Assam) 8 Women’s College Permanent 1966 B+ Rangagora Road Affiliation P.O.Tinsukia, Dist. Tinsukia Pin 786125(Assam) 1 DIBRUGARH DISTRICT NAAC Accreditation Status Sl. COLLEGE NAME & Year of STATUS st nd No ADDRESS Establishment 1 Cycle 2 Cycle Grade CGPA 9 D.D.R College B B 2.35 P.O. Chabua Permanent (19/02/2016) 1971 Dist Dibrugarh Affiliation Pin 786184 (Assam) 10 B++ B++ 2.85 D.H.S. K College (3/5/2017) P.O. Dibrugarh Permanent 1945 Dist. Dibrugarh Affiliation Pin 786001(Assam) 11 D.H.S.K Commerce B++ B College (30/11/2011) Permanent P.O. -

Name Designation NIC Email Ids Shri Vinod Kumar Pipersenia Chief

Name Designation NIC Email ids Shri Vinod Kumar Pipersenia Chief Secretary and Resident Representative, Assam Bhawan, New Delhi, Assam [email protected], [email protected] Shri Bhaskar Mushahary Addl Chief Secretary, Cultural Affairs and Information & Public Relations Deptts., Assam [email protected] Shri Subhash Chandra Das Addl Chief Secretary, Revenue & Disaster Management, Public Health Engineering, Personnel, Pension [email protected] & Public Grievances and AR & Training Deptts., Assam Shri Ram Tirath Jindal Addl Chief Secretary, Industries & Commerce, Mines & Minerals and Handloom, Textiles & Sericulture [email protected] Deptts. & MD, Assam Hydrocarbon & Energy Ltd Rajiv Kumar Bora Addl Chief Secretary, WPT & BC and Soil Conservation Deptts. and Chairman, SLNA (IWMP), Assam [email protected] Shri V. B. Pyarelal Addl Chief Secretary, Power (E), Agriculture, Panchayat & Rural Dev Deptts. and Agruculture [email protected] Production Commissioner, Assam Shri Shyam Lal Mewara Addl Chief Secretary, Transport, Public Enterprises, Labour & Employment and Tea Tribes Welfare [email protected] Deptts., Assam Shri Davinder Kumar Addl Chief Secretary, Environment & Forest and Water Resorces Deptts., Asssam [email protected] Shri V. S. Bhaskar Addl Chief Secretary, Tourism and IT Deptts., Assam [email protected] Shri M. G. V. K. Bhanu Addl Chief Secretary to CM and Addl Chief Secretary, Home, Political, SAD, GAD and Health & [email protected] Family Welfare Deptts., Assam Dr. Ajay Kumar Singh Principal Secretary, Parliamentary Affairs, Minorities Welfare & Dev and Implementation of Assam [email protected] Accrod Deptts, Assam Jayashree Daolagupu Principal Secretary, Karbi Anglong Autonomous Council [email protected] Shri Sameer Kumar Khare Principal Secretary, Finance Deptt. -

Annual Report on Traffic National Waterways: Fy 2020-21

ANNUAL REPORT ON TRAFFIC NATIONAL WATERWAYS: FY 2020-21 INLAND WATERWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA MINISTRY OF PORTS, SHIPPING & WATERWAYS A-13, SECTOR-1, NOIDA- 201301 WWW.IWAI.NIC.IN Inland Waterways Authority of India Annual Report 1 MESSAGE FROM CHAIRPERSON’S DESK Inland Water Transport is (IWT) one of the important infrastructures of the country. Under the visionary leadership of Hon’ble Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi, Inland Water Transport is gaining momentum and a number of initiatives have been taken to give an impetus to this sector. IWAI received tremendous support from Hon’ble Minister for Ports, Shipping & Waterways, Shri Mansukh Mandaviya, to augment its activities. The Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) under Ministry of Ports, Shipping & Waterways, came into existence on 27th October 1986 for development and regulation of inland waterways for shipping and navigation. The Authority primarily undertakes projects for development and maintenance of IWT infrastructure on National Waterways. To boost the use of Inland Water Transport in the country, Hon’ble Prime Minister have launched Jibondhara–Brahmaputra on 18th February, 2021 under which Ro-Ro service at various locations on NW-2 commenced, Foundation stone for IWT terminal at Jogighopa was laid and e-Portals (Car-D and PANI) for Ease-of-Doing-Business were launched. The Car-D and PANI portals are beneficial to stakeholders to have access to real time data of cargo movement on National Waterways and information on Least Available Depth (LAD) and other facilities available on Waterways. To promote the Inland Water Transport, IWAI has also signed 15 MoUs with various agencies during the launch of Maritime India Summit, 2021. -

Formation of the Heterogeneous Society in Western Assam (Goal Para)

CHAPTER- III Formation of the Heterogeneous Society in Western Assam (Goal para) Erstwhile Goalpara district of Western Assam has a unique socio-cultural heritage of its own, identified as Goalpariya Society and Culture. The society is a heterogenic in character, composed of diverse racial, ethnic, religious and cultural groups. The medieval society that had developed in Western Assam, particularly in Goalapra region was seriously influenced by the induction of new social elements during the British Rule. It caused the reshaping of the society to a fully heterogenic in character with distinctly emergence of new cultural heritage, inconsequence of the fusion of the diverse elements. Zamindars of Western Assam, as an important social group, played a very important role in the development of new society and cufture. In the course of their zamindary rule, they brought Bengali Hidus from West Bengal for employment in zamindary service, Muslim agricultural labourers from East Bengal for extension of agricultural field, and other Hindusthani people for the purpose of military and other services. Most of them were allowed to settle in their respective estates, resulting in the increase of the population in their estate as well as in Assam. Besides, most of the zamindars entered in the matrimonial relations with the land lords of Bengal. As a result, we find great influence of the Bengali language and culture on this region. In the subsequent year, Bengali cultivators, business community of Bengal and Punjab and workers and labourers from other parts of Indian subcontinent, migrated in large number to Assam and settled down in different places including town, Bazar and waste land and char areas. -

Political Phenomena in Barak-Surma Valley During Medieval Period Dr

প্রতিধ্বতি the Echo ISSN 2278-5264 প্রতিধ্বতি the Echo An Online Journal of Humanities & Social Science Published by: Dept. of Bengali Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam, India. Website: www.thecho.in Political Phenomena in Barak-Surma Valley during Medieval Period Dr. Sahabuddin Ahmed Associate Professor, Dept. of History, Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam Email: [email protected] Abstract After the fall of Srihattarajya in 12 th century CE, marked the beginning of the medieval history of Barak-Surma Valley. The political phenomena changed the entire infrastructure of the region. But the socio-cultural changes which occurred are not the result of the political phenomena, some extra forces might be alive that brought the region to undergo changes. By the advent of the Sufi saint Hazrat Shah Jalal, a qualitative change was brought in the region. This historical event caused the extension of the grip of Bengal Sultanate over the region. Owing to political phenomena, the upper valley and lower valley may differ during the period but the socio- economic and cultural history bear testimony to the fact that both the regions were inhabited by the same people with a common heritage. And thus when the British annexed the valley in two phases, the region found no difficulty in adjusting with the new situation. Keywords: Homogeneity, aryanisation, autonomy. The geographical area that forms the Barak- what Nihar Ranjan Roy prefers in his Surma valley, extends over a region now Bangalir Itihas (3rd edition, Vol.-I, 1980, divided between India and Bangladesh. The Calcutta). Indian portion of the region is now In addition to geographical location popularly known as Barak Valley, covering this appellation bears a historical the geographical area of the modern districts significance. -

Golaghat ZP-F

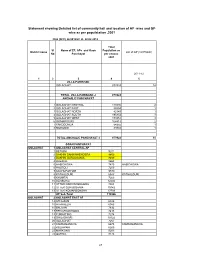

Statement showing Detailed list of community hall and location of AP -wise and GP- wise as per populatation ,2001 FEA (SFC) 26/2012/41 dt. 28.02.2012 Total Sl Name of ZP, APs and Gaon Population as District name List of GP (1st Phash) No Panchayat per census 2001 2011-12 12 3 4 5 ZILLA PARISHAD GOLAGHAT 873924 14 TOTAL ZILLA PARISHAD -I 873924 ANCHALIC PANCHAYAT 1 GOLAGHAT CENTRAL 118546 2 2 GOLAGHAT EAST 88554 1 3 GOLAGHAT NORTH 42349 1 4 GOLAGHAT SOUTH 195854 3 5 GOLAGHAT WEST 179451 3 6 GOMARIGURI 104413 2 7 KAKODONGA 54955 1 8 MORONGI 89802 1 TOTAL ANCHALIC PANCHAYAT -I 873924 14 GOAN PANCHAYAT GOLAGHAT 1 GOLAGHAT CENTRAL AP 1 BETIONI 9201 2 DAKHIN DAKHINHENGERA 9859 3 DAKHIN GURJOGANIA 8457 4 DHEKIAL 8663 5 HABICHOWA 7479 HABICHOWA 6 HAUTOLI 7200 7 KACHUPATHAR 9579 8 KATHALGURI 6543 KATHALGURI 9 KHUMTAI 7269 10 SENSOWA 12492 11 UTTER DAKHINHENGERA 7864 12 UTTER GURJOGANIA 10142 13 UTTER KOMARBONDHA 13798 AP Sub-Total 118546 GOLAGHAT 2 GOLAGHAT EAST AP 14 ATHGAON 6426 15 ATHKHELIA 6983 16 BALIJAN 7892 17 BENGENAKHOWA 7418 18 FURKATING 7274 19 GHILADHARI 10122 20 GOLAGHAT 7257 21 KAMARBANDHA 6678 KAMARBANDHA 22 KOLIAPANI 6265 23 MARKONG 5203 24 OATING 8128 23 12 3 4 5 25 PULIBOR 8908 AP Sub-Total 88554 GOLAGHAT 3 GOLAGHAT NORTH AP 26 MADHYA BRAHMAPUTRA 8091 27 MADHYA MISAMORA 7548 28 PACHIM BRAHMAPUTRA 8895 PACHIM BRAHMAPUTRA 29 PACHIM MISAMORA 8382 30 PUB MISAMORA 9433 AP Sub-Total 42349 GOLAGHAT 4 GOLAGHAT SOUTH AP 31 CHUNGAJAN 13943 32 CHUNGAJAN MAZGAON 5923 33 CHUNGAJAN MIKIR VILLAGES 7401 34 GANDHKOROI 10847 35 GELABIL 12224 36 -

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

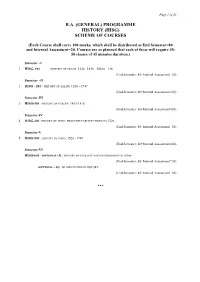

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Pre-Feasibility for Proposed MMLP at Jogighopa

PrePre--Feasibilityfeasibility forReport for ProposedProposed MMLPInter- Modalat Terminal at Jogighopa Jogighopa(DRAFT) FINAL REPORT January 2018 April 2008 A Newsletter from Ernst & Young Contents Executive Summary ......................... 7 Introduction .................................... 9 1 Market Analysis ..................... 11 1.1 Overview of North-East Cargo Market ................................................................................... 11 1.2 Potential for Waterways ............................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.3 Potential for MMLP at Jogighopa .......................................................................................... 16 2 Infrastructure Assessment ..... 19 2.1 Warehousing Area Requirement ........................................................................................... 19 2.2 Facility Area Requirement .................................................................................................... 20 2.3 Handling Equipments ........................................................................................................... 20 3 Financial Assessment ............. 23 3.1 Capital Cost Estimates ......................................................................................................... 23 3.2 Operating Cost Estimates .................................................................................................... 24 3.3 Revenue Estimates ............................................................................................................. -

Expounding Design Act, 2000 in Context of Assam's Textile

EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR Dissertation submitted to National Law University, Assam in partial fulfillment for award of the degree of MASTER OF LAWS Supervised by, Submitted by, Dr. Topi Basar Anee Das Associate Professor of Law UID- SF0217002 National Law university, Assam 2nd semester Academic year- 2017-18 National Law University, Assam June, 2018 SUPERVISOR CERTIFICATE It is to certify that Miss Anee Das is pursuing Master of Laws (LL.M.) from National Law University, Assam and has completed her dissertation titled “EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR” under my supervision. The research work is found to be original and suitable for submission. Dr. Topi Basar Date: June 30, 2018 Associate Professor of Law National Law University, Assam DECLARATION I, ANEE DAS, pursuing Master of Laws (LL.M.) from National Law University, Assam, do hereby declare that the present Dissertation titled "EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR" is an original research work and has not been submitted, either in part or full anywhere else for any purpose, academic or otherwise, to the best of my knowledge. Dated: June 30, 2018 ANEE DAS UID- SF0217002 LLM 2017-18 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT To succeed in my research endeavor, proper guidance has played a vital role. At the completion of the dissertation at the very onset, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my research guide Dr. Topi Basar, Associate professor of Law who strengthen my knowledge in the field of Intellectual Property Rights and guided me throughout the dissertation work. -

Tribal Religion of Lower Assam of North East India

TRIBAL RELIGION OF LOWER ASSAM OF NORTH EAST INDIA 1HEMANTA KUMAR KALITA, 2BHANU BEZBORA KALITA 1Associate Professor, Dept. of Philosophy, Goalpara College, 2Associate Professor, Dept of Assamese, Goalpara College E-mail: [email protected] Abstract - Religion is very sensitive issue and naturally concerned with the sentiment. It is a matter of faith and made neither through logical explanation nor scientific verification. That Religion from its original point of view was emerged as the basic needs and tools of livelihood. Hence it was the creation of human being feeling wonderful happenings bosom of nature at the early stage of origin of religion. It is not exaggeration that tribal people are the primitive bearer of religious belief. However religion for them was not academically explored rather it was regarded as the matter of reverence and submission. If we regard religion from the original point of view the religion then is not discussed under the caprice of ill design.. To think about God, usually provides no scientific value as it is not a matter of verification and material pleasant. Although to think about God or pray to God is also not worthless. Pessimistic and atheistic ideology though not harmful to human society yet the reverence and faith towards God also minimize the inter religious hazards and conflict. It may help to strengthen spirituality and communicability with others. Spiritualism renders a social responsibility in true sense which helps to understand others from inner order of heart. We attempt to discuss some tribal religious festivals along with its special characteristics. Tribal religion though apart from the general characteristic feature it ushers natural gesture and caries tolerance among them. -

Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal

Vol 6 Issue 10 July 2017 ISSN No : 2249-894X ORIGINAL ARTICLE Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal Review Of Research Journal Chief Editors Ashok Yakkaldevi Ecaterina Patrascu A R Burla College, India Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Kamani Perera Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Lanka Welcome to Review Of Research RNI MAHMUL/2011/38595 ISSN No.2249-894X Review Of Research Journal is a multidisciplinary research journal, published monthly in English, Hindi & Marathi Language. All research papers submitted to the journal will be double - blind peer reviewed referred by members of the editorial Board readers will include investigator in universities, research institutes government and industry with research interest in the general subjects. Regional Editor Dr. T. Manichander Advisory Board Kamani Perera Delia Serbescu Mabel Miao Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Spiru Haret University, Bucharest, Romania Center for China and Globalization, China Lanka Xiaohua Yang Ruth Wolf Ecaterina Patrascu University of San Francisco, San Francisco University Walla, Israel Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Karina Xavier Jie Hao Fabricio Moraes de AlmeidaFederal Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), University of Sydney, Australia University of Rondonia, Brazil USA Pei-Shan Kao Andrea Anna Maria Constantinovici May Hongmei Gao University of Essex, United Kingdom AL. I. Cuza University, Romania Kennesaw State University, USA Romona Mihaila Marc Fetscherin Loredana Bosca Spiru Haret University, Romania Rollins College, USA Spiru Haret University, Romania Liu Chen Beijing Foreign Studies University, China Ilie Pintea Spiru Haret University, Romania Mahdi Moharrampour Nimita Khanna Govind P. Shinde Islamic Azad University buinzahra Director, Isara Institute of Management, New Bharati Vidyapeeth School of Distance Branch, Qazvin, Iran Delhi Education Center, Navi Mumbai Titus Pop Salve R.