Pnabs369.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De La Continuité Linguistique Du Préhilalien De Type Jebli Au-Delà Du Territoire Des Jbala

DE LA CONTINUITÉ LINGUISTIQUE DU PRÉHILALIEN DE TYPE JEBLI AU-DELÀ DU TERRITOIRE DES JBALA Fouad BRIGUI* Université Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah - Fès BIBLID [1133-8571] 26 (2019) 01.1-20. Résumé : On considère, généralement, que le territoire des Jbala, au nord-ouest du Maroc, est limité, au sud, par le bassin de l’Oued Ouergha moyen, au nord, par le détroit de Gibraltar et, au nord-est, par le Rif et l’Oriental. Le parler des Jbala, de type préhilalien, se limiterait donc à cet espace géographique. Or, comme l’avaient déjà pressenti et indiqué des sémitisants de l’ère coloniale et comme l’ont confirmé des travaux récents, des parlers présentant des caractéristiques similaires aux parlers des Jbala sont attestés au sud-est et au sud-ouest de cette aire géographique. Cet article fait la synthèse de ces travaux et analyse des données recueillies récemment qui montrent la parenté entre le parler des Jbala et des parlers appartenant à des zones situées en dehors de ce territoire et qui en constituent, probablement, l’extension. Mots-clés : Dialectologie, Préhilalien, Jbala, Maroc, Géographie linguistique, Variation, Variante, Arabe, Substrat Abstract: It is generally considered that the territory of Jbala, in the north-west of Morocco, is bounded on the south by the Oued Ouergha Basin, on the north by the Strait of Gibraltar and on the north-east by the Rif and the Oriental region. The dialect of Jbala, pertaining to the prehilalian type, would be limited to this geographical region. However, as it has been suggested and indicated by some colonial times Semitists and confirmed by recent work, some dialects showing similar features to Jbala dialects are attested in the southeast and southwest of this geographical area. -

Union Sportive Des Cheminots Du Maroc

Union Sportive des Cheminots du Maroc Union Sportive des Cheminots du Maroc -1- Union Sportive des Cheminots du Maroc -2- Union Sportive des Cheminots du Maroc -3- Union Sportive des Cheminots du Maroc -4- Union Sportive des Cheminots du Maroc Distance parcourue : 20,57 km - Durée : 8h - Vitesse moy : 2,53 km/h - Elévation max : 1593 m - Dénivelée : 290 m - Pente max : +34,6% & -27,6% -5- Union Sportive des Cheminots du Maroc I- INTRODUCTION : La randonnée au Parc National de Tazekka, avec évidemment la descente au Gouffre de Friouato, ont été programmées depuis plusieurs années avec les membres du Club de l’Union Sportive des Cheminots du Maroc (U.S.C.M.), malheureusement elles n’ont pas eu lieu suite au manque d’infrastructures pour le vivre et le couvert, en vue du séjour en pleine nature. Il y avait la possibilité de s’installer à la ville de Taza ou dans les villages environnants comme Oued Amlil par exemple, tout en faisant la navette en voiture. Cette option a été écartée d’office, car nous voulions résider au milieu du parc naturel, loin des véhicules, du bruit et de la pollution. Bref, nous cherchons le dépaysement complet, pour profiter pleinement, nuit et jour, de la beauté de la nature et de l’air vivifiant de la moyenne montagne. Même cette fois-ci, la randonnée a failli ne pas avoir lieu, suite à l’annulation unilatérale par SMS et à la dernière minute par le propriétaire d’un gîte récent (construit en 2014) à la suite de problèmes familiaux, d’après le message. -

Chapitre VI La Ville Et Ses Équipements Collectifs

Chapitre VI La ville et ses équipements collectifs Introduction L'intérêt accordé à la connaissance du milieu urbain et de ses équipements collectifs suscite un intérêt croissant, en raison de l’urbanisation accélérée que connaît le pays, et de son effet sur les équipements et les dysfonctionnements liés à la répartition des infrastructures. Pour résorber ce déséquilibre et assurer la satisfaction des besoins, le développement d'un réseau d'équipements collectifs appropriés s'impose. Tant que ce déséquilibre persiste, le problème de la marginalisation sociale, qui s’intensifie avec le chômage et la pauvreté va continuer à se poser La politique des équipements collectifs doit donc occuper une place centrale dans la stratégie de développement, particulièrement dans le cadre de l’aménagement du territoire. La distribution spatiale de la population et par conséquent des activités économiques, est certes liée aux conditions naturelles, difficiles à modifier. Néanmoins, l'aménagement de l'espace par le biais d'une politique active peut constituer un outil efficace pour mettre en place des conditions favorables à la réduction des disparités. Cette politique requiert des informations fiables à un niveau fin sur l'espace à aménager. La présente étude se réfère à la Base de données communales en milieu urbain (BA.DO.C) de 1997, élaborée par la Direction de la Statistique et concerne le niveau géographique le plus fin à savoir les communes urbaines, qui constituent l'élément de base de la décentralisation et le cadre d'application de la démocratie locale. Au recensement de 1982, était considéré comme espace urbain toute agglomération ayant un minimum de 1 500 habitants et qui présentait au moins quatre des sept conditions énumérées en infra1. -

Direction Regionale Du Centre Nord

ROYAUME DU MAROC Office National de l’Électricité et de l’Eau Potable Branche Eau DIRECTION REGIONALE DU CENTRE NORD ________________________________ Projet de renforcement de la production et d’amélioration de la performance technique et commerciale de l’eau potable (PRPTC) Composante : Programme d’amélioration des performances techniques des centres de la Direction Régionale du Centre Nord PLAN D’ACQUISITION DES TERRAINS ET D’INDEMNISATION DES PERSONNES AFFECTEES PAR LE PROJET (PATI-PAP) FINANCEMENT BAD 15 Août 2021 RESUME EXECUTIF DU PATI-PAP 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. CONTEXTE ET JUSTIFICATION DU PROJET 1.2. OBJECTIFS DU PATI-PAP 1.3. METHODOLOGIE D’ELABORATION DU PATI-PAP 2. DESCRIPTION DU PROJET ET DE LA ZONE CONCERNEE 2.1. Description du projet 2.2. Consistance du projet 2.2.1 Consistance des lots 2.2.2. Besoins en foncier 2.3. Présentation de la zone du projet 2.3.1 Présentation géographique 2.3.2. POPULATION ET DEMOGRAPHIE 2.3.3 Urbanisation 2.3.4 Armature urbaine 2.3.5. INFRASTRUCTURES DE BASE 2.3.6. SECTEURS PRODUCTIFS 2.3.7 CAPITAL IMMATERIEL 3. IMPACTS POTENTIELS DU PROJET 3.1. Impacts potentiels positifs 3.2. Impacts potentiels négatifs 3.3. Impacts cumulatifs et résiduels 4. RESPONSABLITES ORGANISATIONNELLES 4.1. Cadre organisationnel nationale 4.2. Responsabilités de la mise en œuvre du présent PATI-PAP 5. PARTICIPATION ET CONSULTATIONS PUBLIQUES 5.1. Participation communautaire/Consultations publiques déjà réalisées 5.2. Consultation des PAPs 5.3. Enquêtes administratives 6. INTEGRATION DES COMMUNAUTES D’ACCUEIL 7. ETUDES SOCIO –ECONOMIQUES : Recensement des personnes affectées par le projet 7.1. -

Advances in Biotechnology July 10-12, 2017 Dubai, UAE

Maryam Hakkour, et al. Adv Biochem Biotehcnol 2017, 02: 05 (Suppl) http://dx.doi.org/10.29011/2574-7258.C1-003 International Conference on Advances in Biotechnology July 10-12, 2017 Dubai, UAE Applied biotechnology to identify new circulating species of leishmaniasis in Taza province, Morocco Maryam Hakkour1,2,3*, Asmae Hmamouch1,4, Mohamed Mahmoud El Alem1,2, Abdelkbir Rhalem3, Hajiba Fellah1, Abderrahim Sadak2 and Faiza Sebti1 1National Reference Laboratory of Leishmaniasis, National Institute of Hygiene, Morocco 2Laboratory of Zoology and General Biology, Morocco 3Agronomy and Veterinary Institute Hassan II 4Laboratory of Microbial Biotechnology, Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, Morocco. Background: In Morocco, leishmaniasis is an endemic disease. Two forms of leishmaniasis are reported: visceral leishmaniasis due to Leishmania infantum and cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by three Leishmania species (Leishmania tropica, Leishmania major and Leishmania infantum). The identification of these species remains important for a better control strategy. In fact, this study aims to apply the biotechnological assays especially the PCR-ITS1-RFLP to identify the Leishmania species circulating and responsible of the recent cases of CL and VL leishmaniasis in taza province which continues to record a high number of cases. Results: The molecular study in Taza Province has shown for the first time the presence of 41% cases of CL due to L. infantum with a percentage (27/63) beside L. tropica. Also, this study shows the coexistence of these two species in the same sectors of Taza, namely Taza High, Oued Amlil, Tahla, Tainaste and Bouhlou. The abundance of L. infantum among the total could be due firstly to the presence (plus touché) of VL due to L. -

MPLS VPN Service

MPLS VPN Service PCCW Global’s MPLS VPN Service provides reliable and secure access to your network from anywhere in the world. This technology-independent solution enables you to handle a multitude of tasks ranging from mission-critical Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), Customer Relationship Management (CRM), quality videoconferencing and Voice-over-IP (VoIP) to convenient email and web-based applications while addressing traditional network problems relating to speed, scalability, Quality of Service (QoS) management and traffic engineering. MPLS VPN enables routers to tag and forward incoming packets based on their class of service specification and allows you to run voice communications, video, and IT applications separately via a single connection and create faster and smoother pathways by simplifying traffic flow. Independent of other VPNs, your network enjoys a level of security equivalent to that provided by frame relay and ATM. Network diagram Database Customer Portal 24/7 online customer portal CE Router Voice Voice Regional LAN Headquarters Headquarters Data LAN Data LAN Country A LAN Country B PE CE Customer Router Service Portal PE Router Router • Router report IPSec • Traffic report Backup • QoS report PCCW Global • Application report MPLS Core Network Internet IPSec MPLS Gateway Partner Network PE Router CE Remote Router Site Access PE Router Voice CE Voice LAN Router Branch Office CE Data Branch Router Office LAN Country D Data LAN Country C Key benefits to your business n A fully-scalable solution requiring minimal investment -

Bulletin L'institut D'hygiène

DIRECTION DE LA SANTE PUBLIQUE BULLETIN DE L'INSTITUT D'HYGIÈNE DU MAROC NOUVELLE SÉRIE TOME 1 ANNÉE 1941 EDITIONS FELIX MONCHO Rue de la Mamounla RABAT 1943 DIRECTION DE LA SANTE PUBLIQUE BULLETIN DE L'INSTITUT D'HYGIÈNE DU MAROC 1 NOUVELLE SÉRIE TOME 1 ANNÉE 1941 EDITIONS FELIX MONCHO Rue de la Mamounia RABAT 1943 SOMMAIRE Pages 5 Le problème de la syphilis nerveuse de l'indigène musulman algérien dans ses rapports avec quelques données d'ethno graphie et de démographie, par F. G. MARILL. 35 Comparaison des résultats de la micro-réaction de Castaneda et Silva modifiée par L. Ch. Brumpt et de la réaction classique de Weil et Félix dans le diagnostic du typhus exanthématique. par Jean GAUD. 45 Deux ans de lutte contre l'ankylostomiase dans les mines de l'Office Chérifien des Phosphates, par A. BECMEUR. 55 Epizootie murine à « Salmonella », par H. FLYE SAINTE-MARIE et G. COUZI. 59 Immunothérapie de la variole. par G. COUZI et J. P. KIRCHER. 69 Note sur l'emploi de l'arsénite de calcium comme poudre larvicide dans la lutte antipaludique. par A. MESSERLIN. 79 Rapport sur l'activité des Services de la Direction de la Santé Publique et de l'Assistance pendant l'année 1941. 133 La lutte antipaludique au Maroc en 1941. par A. MESSERLlN, 147 Rapport sur \' activité de l'Institut d'Hygiène en 1941. 1S3 Rapport sur l'activité du Service central de l'Hygiène scolaire en 1941, par L. PIETRI. le problème de la syphilis nerveuse de l'indigène musulman algérien dans ses rapports avec quelques données d'ethnographie et de démographie par F. -

Résultats Élections

REGION PREFECTURE CONSEIL COMMUNE NOM PRESIDENT ADRESSE OUED‐ED‐DAHAB‐ AOUSSERD commune LAGOUIRA brahim LAKHLIGUI CU. Lagouira, Hay Al MasjiD n° 41, Dakhla ‐ LAGOUIRA urbaine AousserD OUED‐ED‐DAHAB‐ OUED ED‐DAHAB ‐ commune DAKHLA (M) SiDi SLOH EL JAMANI CU. Dakhla ‐ OueD ED Dahab LAGOUIRA LAGOUIRA urbaine LAAYOUNE‐BOUJDOUR‐ LAAYOUNE commune EL MARSA (M) Hassan DERHEM CU. El Marsa, B.P. 36 ‐ Laâyoune SAKIA‐EL‐HAMRA urbaine LAAYOUNE‐BOUJDOUR‐ LAAYOUNE commune LAAYOUNE (M) HamDi OULED RACHID CU. Laâyoune, B.P. 495 ‐ Laâyoune SAKIA‐EL‐HAMRA urbaine LAAYOUNE‐BOUJDOUR‐ LAAYOUNE commune TARFAYA (M) AhmeD AZARQI CU. Tarfaya, B.P. 43 Tarfaya ‐ Laâyoune SAKIA‐EL‐HAMRA urbaine LAAYOUNE‐BOUJDOUR‐ BOUJDOUR commune BOUJDOUR (M) AbDelaziz ABBA CU. BoujDour, BD Hassan II ‐ BoujDour SAKIA‐EL‐HAMRA urbaine GUELMIM‐ES‐SEMARA TATA commune FAM EL HISN (M) MohameD OUDOR CU. Fam El Hisn – Tata urbaine GUELMIM‐ES‐SEMARA TATA commune TIZAGHTE Fatima BOUJNAH CR. Tizaghte, caïDat Issafen ‐ Tata rurale GUELMIM‐ES‐SEMARA TATA commune FOUM ZGUID (M) AbDerrahmane SAIDI CU. Foum ZguiD – Tata urbaine GUELMIM‐ES‐SEMARA TATA commune AKKA (M) RachiD MOULAY CHARIF CU. Akka – Tata urbaine GUELMIM‐ES‐SEMARA TAN TAN commune TAN TAN (M) Ali EL MAZLIOJ CU. Tan‐Tan – Tan‐Tan urbaine GUELMIM‐ES‐SEMARA ES SEMARA commune ES‐SEMARA (M) SiDi MohameD EL CU. Es‐Semara, Hôtel De ville, avenue urbaine JOUMANI MohameD V ‐ Es‐Semara GUELMIM‐ES‐SEMARA ASSA ZAG commune ZAG (M) Atman AILLA CU. Zag – Assa‐Zag urbaine GUELMIM‐ES‐SEMARA ASSA ZAG commune ASSA (M) HamDi OUAISSI CU. Assa – Assa‐Zag REGION PREFECTURE CONSEIL COMMUNE NOM PRESIDENT ADRESSE urbaine GUELMIM‐ES‐SEMARA GUELMIM commune GUELMIM (M) AbDlouhab BELFKIH CU. -

Rapport Diagnostic

Phase 1 : Diagnostic territorial, Orientations d'Aménagement et Projet de plan de 1 développement SOMMAIRE PREAMBULE 3 CHAPITRE 1 : CONTEXTE GENERAL D’INTEGRATION DU CENTRE DE SIDI AHMED ZERROUK 4 INTRODUCTION 5 PRESENTATION DE L’AIRE DE L’ETUDE – ENVIRONNEMENT REGIONAL ET PROVINCIAL 6 1- DONNEES NATURELLES 6 1-1 Situation géographique 6 1-2 Le cadre naturel 8 1-3 Le climat 8 1-4 Les ressources hydriques 9 1-5 La forêt 10 2- CARACTERISTIQUES DEMOGRAPHIQUES. 10 2-1 Répartition spatiale de la population 10 2-2 Structure de la population 12 2-3 Activité 14 3- DONNEES ECONOMIQUES 14 3-1 Le secteur primaire 14 3-2 Le secteur secondaire 16 3-3 Le secteur tertiaire 19 4- HABITAT ET DEVELOPPEMENT URBAIN 21 5- INFRASTRUCTURES DE BASE 22 5-1 Infrastructures de communication 22 5-2 Réseaux divers 24 6- EQUIPEMENTS SOCIO-COLLECTIFS 28 6-1 Equipements sanitaires 28 6-2 Education 28 6-3 Formation professionnelle 29 6-4 Equipements culturels et sportifs 30 7- ENVIRONNEMENT 30 8- CONTRAINTES ET POTENTIALITES DE DEVELOPPEMENT REGIONAL 31 8-1 Potentialités et atouts 31 8-2 Contraintes et entraves de développement 32 CHAPITRE 2 : ANALYSE DIAGNOSTIC DE L’ETAT ACTUEL DE LA COMMUNE RURALE DE TAIFA ET DU CENTRE DE SIDI AHMED ZERROUK 34 1- CARACTERISTIQUES NATURELLES 35 1-1 Situation géographique 35 1-2 Climat 36 1-3 Relief 36 1-4 Ressources en eau 37 Plan de développement de l’agglomération de Sidi Ahmed Zerrouk BENMIMOUN M’Hamed Architecte-Urbaniste - Rabat Novembre 2016 Phase 1 : Diagnostic territorial, Orientations d'Aménagement et Projet de plan de 2 développement 2. -

Etude Du Plan D'aménagement De La Ville D'aknoul, Province De Taza

Marché N°01/2016 : Etude du Plan d’Aménagement de la ville d’Aknoul, Province de Taza Marché N°01/2016 : Etude du Plan d’Aménagement de la ville d’Aknoul, Province de Taza SOMMAIRE I. PROBLEMATIQUE TERRITORIALE 5 I.1. Bref Aperçu 5 I.2. Les Approches Territoriales 7 I.2.1. Approche Régionale 7 I.2.1.1. Démographie 8 I.2.1.2. Activités économiques 9 I.2.1.3. Artisanat, industrie et tourisme 10 I.2.1.4. Couloirs de développement 10 I.2.2. APPROCHE PROVINCIALE 12 I.2.2.1. Données générales 12 I.2.2.2. Démographie 14 I.1.2.3. Infrastructure 15 I.1.2.4. Agriculture 15 I.1.2.5. Industrie 16 I.1.2.6. Artisanat 17 I.1.2.7. Tourisme 17 I.1.2.8. Données sociales 18 II. ANNALYSE SOCOIOECONOMIQUE DE LA 19 COMMUNE D’AKNOUL II.1. Cadre administratif 22 II.2. Données naturelles et physiques 26 II.3. Analyse démographique 28 II.3.1. Evolution et accroissement démographique 28 II.3.2. Caractéristiques démographiques 29 II.3.3. Structure de la population par groupes d’âges 29 II.3.4. Pyramide des âges de population de la ville d’Aknoul (aire de l’étude) 32 II.3.5. La fécondité 33 II.3.6. La migration 34 II.4. Profil social 35 II.4.1. Structure matrimoniale 35 II.4.2. Education et alphabétisation en 2014 36 II.4.3. Analyse Socio-économique 36 II.4.4. Activité et emploi 37 II.4.5. -

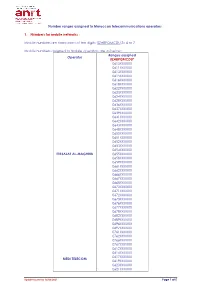

Number Ranges Assigned to Moroccan Telecommunications Operators

Number ranges assigned to Moroccan telecommunications operators 1. Numbers for mobile networks : Mobile numbers are composed of ten digits: 0ZABPQMCDU Z= 6 or 7. Mobile numbers assigned to mobile operators are as below: Ranges assigned Operator 0ZABPQMCDU* 0610XXXXXX 0611XXXXXX 0613XXXXXX 0615XXXXXX 0616XXXXXX 0618XXXXXX 0622XXXXXX 0623XXXXXX 0624XXXXXX 0628XXXXXX 0636XXXXXX 0637XXXXXX 0639XXXXXX 0641XXXXXX 0642XXXXXX 0643XXXXXX 0648XXXXXX 0650XXXXXX 0651XXXXXX 0652XXXXXX 0653XXXXXX 0654XXXXXX ITISSALAT AL-MAGHRIB 0655XXXXXX 0658XXXXXX 0659XXXXXX 0661XXXXXX 0662XXXXXX 0666XXXXXX 0667XXXXXX 0668XXXXXX 0670XXXXXX 0671XXXXXX 0672XXXXXX 0673XXXXXX 0676XXXXXX 0677XXXXXX 0678XXXXXX 0682XXXXXX 0689XXXXXX 0696XXXXXX 0697XXXXXX 0761XXXXXX 0762XXXXXX 0766XXXXXX 0767XXXXXX 0612XXXXXX 0614XXXXXX 0617XXXXXX MEDI TELECOM 0619XXXXXX 0620XXXXXX 0621XXXXXX Update issued on 14/06/2021 Page 1 of 5 0625XXXXXX 0631XXXXXX 0632XXXXXX 0644XXXXXX 0645XXXXXX 0649XXXXXX 0656XXXXXX 0657XXXXXX 0660XXXXXX 0663XXXXXX 0664XXXXXX 0665XXXXXX 0669XXXXXX 0674XXXXXX 0675XXXXXX 0679XXXXXX 0684XXXXXX 0688XXXXXX 0691XXXXXX 0693XXXXXX 0694XXXXXX 0770XXXXXX 0771XXXXXX 0772XXXXXX 0773XXXXXX 0774XXXXXX 0775XXXXXX 0777XXXXXX 0526XXXXXX 0527XXXXXX 0533XXXXXX 0534XXXXXX 0540XXXXXX 0546XXXXXX 0547XXXXXX 0550XXXXXX 0553XXXXXX 060XXXXXXX 0626XXXXXX 0627XXXXXX 0629XXXXXX 0630XXXXXX 0633XXXXXX 0634XXXXXX Wana Corporate 0635XXXXXX 0638XXXXXX 0640XXXXXX 0646XXXXXX 0647XXXXXX 0680XXXXXX 0681XXXXXX 0687XXXXXX 0690XXXXXX 0695XXXXXX 0698XXXXXX 0699XXXXXX 0700XXXXXX 0701XXXXXX 0702XXXXXX 0703XXXXXX -

Code Géographique Du Maroc

Région: OUED ED-DAHAB-LAGOUIRA |_0_|_1_| Province ou Cercle Commune ou Arrondissement Préfecture Libellé Code Libellé Code Libellé Code Lagouira (M) 066.01.03 Aghouinite 066.03.03 Aousserd 066.03.05 Aousserd 066 Aousserd 066.03 Tichla 066.03.07 Zoug 066.03.09 Bir Gandouz 066.05 Bir Gandouz 066.05.03 Dakhla (M) 391.01.01 Bir Anzarane 391.05.01 Gleibat El Foula 391.05.03 Oued-Ed- Bir Anzarane 391.05 391 Mijik 391.05.05 Dahab Oum Dreyga 391.05.07 El Argoub 391.09.01 El Argoub 391.09 Imlili 391.09.03 Région:LAAYOUNE-BOUJDOUR-SAKIA EL HAMRA |_0_|_2_| Province ou Cercle Commune ou Arrondissement Préfecture Libellé Code Libellé Code Libellé Code Boujdour (M) 121.01.01 Gueltat Zemmour 121.03.01 Boujdour 121 Jraifia 121.03 Jraifia 121.03.03 Lamssid 121.03.05 El Marsa (M) 321.01.01 Laayoune (M) 321.01.03 Tarfaya (M) 321.01.05 Boukraa 321.03.01 Laayoune 321.03 Dcheira 321.03.03 Laayoune 321 Foum El Oued 321.03.05 Akhfennir 321.05.01 Daoura 321.05.03 Tarfaya 321.05 El Hagounia 321.05.05 Tah 321.05.07 Région: GUELMIM-ES-SEMARA |_0_|_3_| Province ou Cercle Commune ou Arrondissement Préfecture Libellé Code Libellé Code Libellé Code Assa (M) 071.01.01 Zag (M) 071.01.03 Aouint Lahna 071.03.01 Assa-Zag 071 Assa 071.03 Aouint Yghomane 071.03.03 Touizgui 071.03.05 Al Mahbass 071.05.01 Zag 071.05 Labouirat 071.05.03 Es-semara (M) 221.01.01 Amgala 221.03.01 Haouza 221.03.03 Es-Semara 221 Es-Semara 221.03 Jdiriya 221.03.05 Sidi Ahmed Laarouss 221.03.07 Tifariti 221.03.09 Bouizakarne (M) 261.01.01 Guelmim (M) 261.01.03 Aday 261.03.01 Ait Boufoulen 261.03.03 Amtdi