Epi-Revel@Nice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POLITICAL PARODY and the NORTHERN IRISH PEACE PROCESS Ilha Do Desterro: a Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, Núm

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Phelan, Mark (UN)SETTLEMENT: POLITICAL PARODY AND THE NORTHERN IRISH PEACE PROCESS Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 58, enero-junio, 2010, pp. 191-215 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348696010 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative (Un)Settlement: Political Parody and... 191 (UN)SETTLEMENT: POLITICAL PARODY AND THE NORTHERN IRISH PEACE PROCESS 1 Mark Phelan Queen’s University Belfast Human beings suffer, They torture one another, They get hurt and get hard No poem or play or song Can fully right a wrong Inflicted and endured... History says, Don’t hope On this side of the grave. But then, once in a lifetime The longed-for tidal wave Of justice can rise up, And hope and history rhyme. (Heaney, The Cure at Troy 77) Ilha do Desterro Florianópolis nº 58 p. 191-215 jan/jun. 2010 192 Mark Phelan Abstract: This essay examines Tim Loane’s political comedies, Caught Red-Handed and To Be Sure, and their critique of the Northern Irish peace process. As “parodies of esteem”, both plays challenge the ultimate electoral victors of the peace process (the Democratic Unionist Party and Sinn Féin) as well as critiquing the cant, chicanery and cynicism that have characterised their political rhetoric and the peace process as a whole. -

Depictions of Femininity in Irish Revolutionary Art Pearl Joslyn

Gender and Memory: Depictions of This paper compares depictions of the mythological personification of Ireland, Femininity in Irish Revolutionary 1 Kathleen ni Houlihan, with the true stories Art of female active combatants to investigate Pearl Joslyn where collective memory of the Easter Senior, History and Global Studies Rising diverged from the truth. By presenting these examples against the The popular narrative of the 1916 backdrop of traditional gender roles in the Easter Rising, which marked the start of the era of Irish state-building, this paper hopes Irish Revolution, reflected highly gendered to contribute to the study of gender in views of masculine and feminine roles in revolutionary Irish history. Additionally, this armed rebellion. In the gendered paper offers a critique of the over-reliance environment of British-ruled Ireland at the on romanticized versions of the past that end of the Victorian Era, women were derive from fiction in collective memory. frequently pushed out of active combat This paper will shed light on the women of roles. Instead, women were expected to aid the revolution, whose vita role in Irish the young men of Ireland, who were history is often overlooked. frequently sent to their deaths, a trope not uncommon in the history of revolution and When Lady Augusta Gregory and William Butler Yeats wrote Cathleen ni warfare. These gender roles were reflected Houlihan in 1901, they did not expect it to in the Irish arts during the years surrounding the 1916 Easter Rising. Depictions of become a rallying cry for revolution. The masculinity and femininity in Irish play, however, became a sort of call to arms Nationalist art often portrayed women as among young nationalists who saw a vision helpless victims of British oppression, who of renewal in the play’s conclusion. -

Lady Jane Wilde As the Celtic Sovereignty

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2008-12-01 Resurrecting Speranza: Lady Jane Wilde as the Celtic Sovereignty Heather Lorene Tolen Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Tolen, Heather Lorene, "Resurrecting Speranza: Lady Jane Wilde as the Celtic Sovereignty" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 1642. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1642 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RESURRECTING SPERANZA: LADY JANE WILDE AS THE CELTIC SOVEREIGNTY by Heather L. Tolen A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English Brigham Young University December 2008 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Heather L. Tolen This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. ______________________________ ___________________________________ Date Claudia Harris, Chair ______________________________ ___________________________________ Date Dr. Leslee Thorne-Murphy ______________________________ ___________________________________ -

Kathleen Ni Houlihan

St Brendan The Navigator Feast Day May 16th Ancient Order of Hibernians St Brendan the Navigator Division Mecklenburg County Division # 2 ISSUE #3 MONTHLY NEWSLETTER VOLUME# 5 March 2013 Our next business meeting is on Thursday, March 14th at 7:30 PM St Mark’s Parish Center, Room 200 2013 Officers Chaplain Father Matthew Codd President Ray FitzGerald Vice President Dave Foley Secretary Tom Vaccaro Treasurer Chris O’Keefe Fin. Secretary Ron Haley Standing Committee Pat Phelan Marshall Brian Bourque Sentinel Frank Fay Past President Joseph Dougherty www.aohmeck2.org "Níor bhris focal maith fiacail riamh" A good word never broke a tooth President’s Message Brothers, We are now entering our busiest month, the month of the Irish. It’s time to be doubly proud of our heritage. If you haven’t been able to participate in or volunteer to help at our events or activities in the past, this is the perfect time to make that extra effort. There is much to be done and we can’t leave it up to a handful of members to do it all. Keep alert to our e-mails, website and information in this Newsletter to see how you can help. As we approach St. Patrick’s Day, be alert to stores, kiosks, vendors promoting or selling merchandise that defames or disparages the Irish heritage. Typical are t-shirts depicting the Irish as drunkards and the like. Don’t hesitate to complain either in person or in writing to the vendor that you find this offensive and politely ask them to discontinue displaying selling them. -

The Political Commitment in the Poetry of Seamus Heaney

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL "PROTECTIVE COLOURING" - THE POLITICAL COMMITMENT IN THE POETRY OF SEAMUS HEANEY BEING A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL BY ALAIN THOMAS YVON SINNER, BA APRIL 1988 PREFACE I came to Heaney's poetry through FIELD WORK, which I read for a seminar on contemporary British poetry when I was studying English at the University of Hull. At the time I knew nothing whatsoever about post-Yeatsian Irish poetry and so I was agreeably surprised by the quality of Heaney's work. Initially, it was not so much the contents of his poems, but the rhythms, the sound patterns, the physical immediacy of his poetry which I admired most. Accordingly, I concentrated on Heaney's nature and love poems. His political verse requires the reader to be more or less well informed about what was and still is going on in Northern Ireland and it was only gradually that I acquired such knowledge. After FIELD WORK, I read the SELECTED POEMS 1965-1975 and they became a kind of journey through the diverse aspects of Heaney's multi-faceted work. In the course of six years' research on Heaney I have come to study other poets from Ulster as well and, though I still feel that Heaney is the most promising talent, it seems to me that Ireland is once again making a considerable contribution to English literature. Heaney is definitely on his way to becoming a major poet. The relevance of his work is not limited to the Irish context; he has something to say to ENGLISH ' ********************************************************* 1 1 A1-1-i 1988 Summary of Thesis submitted for PhD degree by Alain T.Y. -

Ireland, Mother Ireland': an Essay in Psychoanalytic Symbolism

'IRELAND, MOTHER IRELAND': AN ESSAY IN PSYCHOANALYTIC SYMBOLISM Cormac Gallagher Introduction On June 21 1922, as the Irish War of Independence was tipping over into the Civil War, - two months later Harry Boland, Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins would all be dead - on the longest day of 1922 then, Ernest Jones read a paper to the British Psychoanalytical Society entitled: The island of Ireland: a psychoanalytical contribution to political psychology'.1 In it, he argued that the geographic fact that Ireland is an island has played an important and underestimated part in the idea that the Irish have formed of their own country. The signifier 'Ireland' has become particularly associated with the unconscious maternal complex to which all kinds of powerful affects are attached and this in turn has played a part in the formation of Irish character and in the age-old refusal of the Irish to follow the Scots and the Welsh along a path of peaceful and beneficial co-operation with England. The 1922 paper applied to Anglo-Irish relations, which then as now were at a crucial turning point, the theses of Jones' classic 1916 article on The Theory of Symbolism2 which is known to contemporary psychoanalysts mainly through a long and detailed study of it by Jacques Lacan. Lacan argued that far from being of merely historical or even pre-historical interest this paper articulated issues that are still at the heart of the debate concerning the proper object of psychoanalysis and the clinical impasses that result from a failure to articulate correctly the status of this object. -

Notes on the Plays

Notes on the Plays THE SHADOW OF A GUNMAN The action of the play takes place in May 1920 at the height of the Anglo-Irish war, fought between the British forces and the Irish Republican Army. Here, the former are represented by an irregular militia of Black and Tans and Auxiliaries, recruited for counter terrorist activities in support of the regular troops and the Royal Irish Constabulary. By mid 1920 the ordinary people of Ireland, many of whom had been initially hostile to the revolutionaries (as can be seen in The Plough and the Stars), had become far more sympathetic to them-and openly antagonistic to the forces of the Crown, mostly as a result of the conduct of the irregular troops who often behaved far more lawlessly than the Auxiliary does in The Shadow of a Gunman. Acri 3 A return room: an extra room added to a tenement, eked out of space not originally intended for a room for habitation. A return is an architectural term for 'the part of a wall or continuous moulding, frieze, etc. which turns away (usually at right angles) from the previous direction'. 3 Hilljoy Square: Mountjoy Square, Dublin, where the playwright lived for some months in 1920-21. 3 'the might of design ... beauty everlasting': quotation from a speech that begins 'I believe in Michael Angelo, Velasquez, and Rembrandt', delivered by the dying painter Louis Dubedat in the fourth act of Bernard Shaw's The Doctors Dilemma. 4 Or when sweet Summer's ... life is only ours: stanza from 'Sun shadows', early poem by O'Casey, printed in Windfalls (London, 1934) p. -

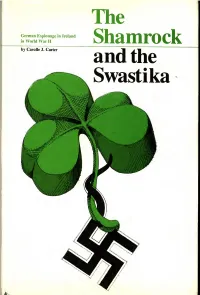

The Shamrock and the Swastika

The German Espionage in Ireland in World War II Shamrock by Carolle J. Carter and the $ 12.95 Incredible and revealing! These words truly de- scribe this thorough, documented study of German espionage in Ireland in World War II and of Eamon De Valera’s battle to keep his country neutral during this crucial period in history. This “spy story” is based on official and unoffi- cial sources, especially captured German files used here extensively for the first time, and on personal interviews with many of the participants—Irish government officials, Irish Republican Army mem- bers, and the German agents. It discloses to what extent the IRA collaborated with the Germans in their efforts to achieve na- tionalist goals. And it exposes the incredible, al- most unbelievable, bungling of the German Ab- wehr (Military Espionage) in its Irish mission because of internal jealousies, falsified reports, and amateurish agents. Although it may read like a Peter Sellers movie at times, this book, points out one of the chief participants, marks a considerable advance in our knowledge of what really went on publicly and secretly in Ireland in this exciting period. The apparent lack of support in Ireland’s south- ern twenty-six counties for Britain’s life and death struggle in World War II brought sharp criticism from English and American leaders, as well as many exaggerated tales about the extent of Irish cooperation with Germany and the hospitality ac- corded German spies by the IRA. In fact, the Irish government was unsympathetic toward Germany and sought to suppress the IRA, but few people (continued on back flap) THE SHAMROCK AND THE SWASTIKA The German Espionage in Ireland vy* m^v t in World War II OllCtllll ULK by Carolle J. -

National Allegory and Maternal Authority in Anglo-Irish Literature

Mother England, Mother Ireland: National Allegoryand Maternal Authority in Anglo-Irish Literature and Culture, 1880-1922 Andrea Christina Bobotis Greenville, South Carolina MA in English Literature and Language, University of Virginia, 2002 BA in English Literature and Language, Furman University, 1998 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degreeof Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Virginia May,2007 Abstract "Mother England, Mother Ireland" proposes a new way of reading allegories of nation-building and national identity in Anglo-Irish literature at the end of the nineteenth century. I argue that authors who claimed affiliations with both England and Ireland (Maud Gonne, Lady Augusta Gregory, Bram Stoker, and Oscar Wilde) exploited the capacity of allegory to infiltratea range of genres and, in doing so, discovered hidden potential in the links between motherhood and motherland. Examining nonfiction, novels, drama, speeches, and public spectacles, I show how these writers adapted allegorical representations of Ireland as a mother not only to confrontIreland's vexed political and cultural relationship with England, but also to explore cross-cultural links between Ireland and Britain's outlying colonies. ii Table of Contents Introduction: Reconsidering National Allegory 1 Rival Maternities: Maud Gonne, Queen Victoria, and the Reign of the Political Mother 20 Collaborative Motherhood in Lady Gregory's Nonfiction 62 The Princess as Artist: Mother-Daughter Relations in the Irish Allegory of Oscar Wilde's Salome 114 Technologies of the Maternalin Bram Stoker's The Lady of the Shroud 154 Bibliography 190 Endnotes 201 Introduction Reconsidering National Allegory In the late 1880s the Anglo-Irishwoman Fanny Parnellwas at the height of her popularity as an Irish nationalist poet. -

International Yeats Studies, Volume 5, Issue 1

International Yeats Studies Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 1 April 2021 International Yeats Studies, Volume 5, Issue 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/iys Recommended Citation (2021) "International Yeats Studies, Volume 5, Issue 1," International Yeats Studies: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/iys/vol5/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Yeats Studies by an authorized editor of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. International Yeats Studies vol. 5 Copyright 2021 by Clemson University ISBN 978-1-63804-011-8 Published by Clemson University Press in Clemson, South Carolina To order copies, contact Clemson University Press at 116 Sigma Dr., Clemson, South Carolina, 29634 or order via our website: www.clemson.edu/press. Contents Volume 5, Issue 1 Special Issue: Wheels and Butterflies Margaret Mills Harper Introduction to the Introductions: Wheels and Butterflies as Comedy 1 Charles I. Armstrong Cornered: Intimate Relations in The Words upon the Window-Pane 11 Inés Bigot The “endless Dance of Contrapuntal Energy”: Conflict and Disunity in Fighting the Waves 27 Alexandra Poulain “[...] but a play”: Laughter and the Reinvention of Theater in The Resurrection 41 Akiko Manabe “Are you that flighty?” “I am that flighty.”: The Cat and the Moon and Kyogen Revisited 53 Reviews Lloyd (Meadhbh) Houston Science, Technology, and Irish Modernism, edited by Kathryn Conrad, Cóilín Parsons, and Julie McCormick Weng 71 Claire Nally A Reader’s Guide to Yeats’s A Vision, by Neil Mann 79 Maria Rita Drumond Viana The Collected Letters of W. -

Afterword: the Act and the Word

Afterword: The Act and the Word Olwen Fouéré Actors are still categorized as mere interepreters within the artistic hier- arachies of Irish theatre. Of course, many of us have bowed to that definition and sadly trundle along, madly interpreting. I wonder why that is. As an actor/actress – or dare I say it – as an artist, as one who seeks, I am conscious that theatre demands everything of the actor’s human form. It demands everything of the body who acts and receives all the knowledge we will ever need. The body is the delta, alpha and omega of theatre and the actor’s power resides there, free from the perceived tyranny of the word. This is the task. It is as simple as putting words on a page and it is not easy, as any writer will tell you. A lot of things can get in the way. For instance, the idea that as I am woman I am therefore called an actress. An Actress might be an icon, languorous and eternally poised somewhere dangerously close to Sunset Boulevard. She lives alone and remains forever exotic and unattainable. There are times when I like that idea and court it for my own wicked amusement. The idea that as an actress I am brilliant at displaying emotion and can move an audience to tears, not to mention the nice writer in the back row. Even the idea that this is perhaps an actress’s job, to be so ‘moving’ in the role that everyone says she really must play Nora in A Doll’s House or later even Medea so that she can demonstrate her remarkable histrionic range – but mind, not too much rage, there madness lies, keep charming the audience if you can and don’t be too ‘strong’ or it will go against you. -

The Allegorical Ireland Figure in the Irish National Theatre, 1899-1926

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1996 The Allegorical Ireland Figure in the Irish National Theatre, 1899-1926 Svetlana Novakovic Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Novakovic, Svetlana, "The Allegorical Ireland Figure in the Irish National Theatre, 1899-1926" (1996). Dissertations. 3589. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3589 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1996 Svetlana Novakovic LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE ALLEGORICAL IRELAND FIGURE IN THE IRISH NATIONAL THEATRE, 1899-1926 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY SVETLANA NOVAKOVIC CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY 1996 Copyright by Svetlana Novakovic, 1995 All rights reserved. ll ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Janet Nolan and Pat Casey for patiently reading through my drafts and offering suggestions. I would like to express special gratitude to Verna Foster not only for her abundant technical assistance but also for her enthusiastic belief in Irish drama as performance. The themes I explore in this dissertation would not have been comprehensible without her perspective nor would the long incessant work have been tolerable without her belief that Nora Burke and Juno Boyle are something more than characters in a text.