Farmers' Planting and Management of Indigenous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Big Governance Issues in Botswana

MARCH 2021 THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE AFRICAN PEER REVIEW MECHANISM Contents Executive Summary 3 Acknowledgments 7 Acronyms and Abbreviations 8 What is the APRM? 10 The BAPS Process 12 Ibrahim Index of African Governance Botswana: 2020 IIAG Scores, Ranks & Trends 120 CHAPTER 1 15 Introduction CHAPTER 2 16 Human Rights CHAPTER 3 27 Separation of Powers CHAPTER 4 35 Public Service and Decentralisation CHAPTER 5 43 Citizen Participation and Economic Inclusion CHAPTER 6 51 Transparency and Accountability CHAPTER 7 61 Vulnerable Groups CHAPTER 8 70 Education CHAPTER 9 80 Sustainable Development and Natural Resource Management, Access to Land and Infrastructure CHAPTER 10 91 Food Security CHAPTER 11 98 Crime and Security CHAPTER 12 108 Foreign Policy CHAPTER 13 113 Research and Development THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA: A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE APRM 3 Executive Summary Botswana’s civil society APRM Working Group has identified 12 governance issues to be included in this submission: 1 Human Rights The implementation of domestic and international legislation has meant that basic human rights are well protected in Botswana. However, these rights are not enjoyed equally by all. Areas of concern include violence against women and children; discrimination against indigenous peoples; child labour; over reliance on and abuses by the mining sector; respect for diversity and culture; effectiveness of social protection programmes; and access to quality healthcare services. It is recommended that government develop a comprehensive national action plan on human rights that applies to both state and business. 2 Separation of Powers Political and personal interests have made separation between Botswana’s three arms of government difficult. -

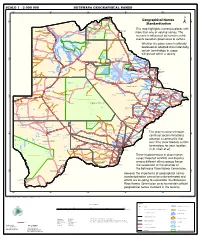

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe -

Republic of Botswana the Project for Enhancing National Forest Monitoring System for the Promotion of Sustainable Natural Resource Management

DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY AND RANGE RESOURCES (DFRR) MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION AND TOURISM (MENT) REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA THE PROJECT FOR ENHANCING NATIONAL FOREST MONITORING SYSTEM FOR THE PROMOTION OF SUSTAINABLE NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT DECEMBER 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY(JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. JAPAN FOREST TECHNOLOGY ASSOCIATION GE JR 17-131 DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY AND RANGE RESOURCES (DFRR) MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION AND TOURISM (MENT) REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA THE PROJECT FOR ENHANCING NATIONAL FOREST MONITORING SYSTEM FOR THE PROMOTION OF SUSTAINABLE NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT DECEMBER 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY(JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. JAPAN FOREST TECHNOLOGY ASSOCIATION DFRR/JICA: Botswana Forest Distribution Map Zambia Angola Zambia Legend KASANE Angola ! ! Settlement CountryBoundary Riparian Forest Typical Forest Woodland Zimbabwe Zimbabwe Bushland/Shrubland Savanna/Grassland/Forbs MAUN ! NATA Baregorund ! TUTUME ! Desert/Sand Dunes Marsh/Wetland FRANCISTOWN Waterbody/Pan ! ORAPA Namibia ! TONOTA ! GHANZI Angola Zambia Namibia ! SELEBI-PHIKWE BOBONONG ! ! Zimbabwe SEROWE ! PALAPYE ! Namibia MAHALAPYE ! South Africa KANG ! MOLEPOLOLE MOCHUDI ! ! JWANENG ! GABORONE ! ´ 0 50 100 200 RAMOTSWA ! KANYE Kilometres ! Coordinate System: GCS WGS 1984 Datum: WGS 1984 LOBATSE ! Botswana Forest Distribution Map Produced from -

List of Schools Visited for Monitoring Visits

LIST OF SCHOOLS VISITED FOR MONITORING VISITS CENTRAL INSPECTORAL AREA LOCATION NAME OF SCHOOL MMADINARE Diloro Diloro MMADINARE Mmadinare Kelele MMADINARE Kgagodi Kgagodi MMADINARE Mmadinare Mmadinare MMADINARE Mmadinare Phethu Mphoeng MMADINARE Robelela Robelela MMADINARE Gojwane Sedibe MMADINARE Serule Serule MMADINARE Mmadinare Tlapalakoma BOTETI Rakops Etsile BOTETI Khumaga Khumaga BOTETI Khwee Khwee BOTETI Mopipi Manthabakwe BOTETI Mmadikola Mmadikola BOTETI Letlhakane Mokane BOTETI Mokoboxane Mokoboxane BOTETI Mokubilo Mokubilo BOTETI Moreomaoto Moreomaoto BOTETI Mosu Mosu BOTETI Motlopi Motlopi BOTETI Letlhakane Retlhatloleng Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Boitshoko Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Boswelakgomo Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Tebogo BOBIRWA Bobonong Bobonong BOBIRWA Gobojango Gobojango BOBIRWA Bobonong Mabumahibidu BOBIRWA Bobonong Madikwe BOBIRWA Mogapi Mogapi BOBIRWA Molalatau Molalatau BOBIRWA Bobonong Rasetimela BOBIRWA Semolale Semolale BOBIRWA Tsetsebye Tsetsebye 1 | P a g e MAHALAPYE WEST Bonwapitse Bonwapitse MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye Leetile MAHALAPYE WEST Mokgenene Mokgenene MAHALAPYE WEST Moralane Moralane MAHALAPYE WEST Mosolotshane Mosolotshane MAHALAPYE WEST Otse Setlhamo MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye St James MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye Tshikinyega MHALAPYE EAST Mahalapye Flowertown MHALAPYE EAST Mahalapye Mahalapye MHALAPYE EAST Matlhako Matlhako MHALAPYE EAST Mmaphashalala Mmaphashalala MHALAPYE EAST Sefhare Mmutle PALAPYE NORTH Goo-Sekgweng Goo-Sekgweng PALAPYE NORTH Goo-Tau Goo-Tau -

Lea Smme Directory 2016

www.lea.co.bw LEA SMME DIRECTORY 2016 Manufacturing Tourism Agriculture Services DISCLAIMER The information published in this document is for the sole purpose of marketing LEA registered SMME’s. LEA shall not be liable for any loss howsoever incurred as a result of use of content on this document in whole or in part. LEA further does not warrant that a business placing reliance on this document will generate certain results, nor does LEA guarantee any particular outcome of the application of the contents hereof to any situation. The clients and users hereby indemnifies and holds harmless LEA, its successors in title, agents and employees against any and all claims for loss or inconvenience arising out of the implementation by the user of the contents of this document or any annexure or addendum to it. www.lea.co.bw LEA SMME Directory 2016 LEA INCUBATORS NETWORK Vision To be the centre of excellence for entrepreneurship and sustainable SMME development in Botswana. LEA Mission To promote and facilitate entrepreneurship and SMME development through targeted interventions, in pursuit of economic diversification. Values Self-driven– We are passionate, eager to learn, persistent and determined to achieve personal goals so that the entire team achieves its desired results. Trasformational GABORONE LEATHER INDUSTRIES GLEN VALLEY HORTICULTURE leadership- We are inspired and self-led, motivated, INCUBATOR INCUBATOR innovative, innovative and Plot 4799 / 4800 Plot 63069 accountable to achieve Old Bedu Station Extension 67 maximum potential in a favourable environment. Macheng Way Private Bag X035 Private Bag 0301 Glen Valley Partnership- Through our Gaborone, Botswana Gaborone Botswana internal teamvork and Tel: (+267) 3105330 Tel: (+267) 3186309 effective partnership with stakeholders, our efforts are Fax: (+267) 3105334 Fax: (+267) 3186437 synergized resulting in the success of our clientele. -

List of Cities in Botswana

List of cities in Botswana The following is a list of cities and towns in Botswana with population of over 3,000 citizens. State capitals are shown in boldface. Population Female Rank Name District Census District [1] Male Population 2001. Population 1. Gaborone South-East District Gaborone 186,007 91,823 94,184 2. Francistown North-East District Francistown 83,023 40,134 42,889 3. Molepolole Kweneng District Kweneng East 62,739 28,617 34,122 4. Serowe Central District Central Serowe/Palapye 52,831 25,400 27,431 5. Selibe Phikwe Central District Selibe Phikwe 49,849 24,334 25,515 6. Maun North-West District Ngamiland East 49,822 23,714 26,108 7. Kanye Southern District Ngwaketse 48,143 22,451 25,692 8. Mahalapye Central District Central Mahalapye 43,538 21,120 22,418 9. Mogoditshane Kweneng District Kweneng East 40,753 20,972 19,781 10. Mochudi Kgatleng District Kgatleng 39,349 18,490 20,859 11. Lobatse South-East District Lobatse 29,689 14,202 15,487 12. Palapye Central District Central Serowe/Palapye 29,565 13,995 15,570 13. Ramotswa South-East District South East 25,738 12,027 13,711 14. Moshupa Southern District Ngwaketse 22,811 10,677 12,134 15. Tlokweng South-East District South East 22,038 10,568 11,470 16. Bobonong Central District Central Bobonong 21,020 9,877 11,143 17. Thamaga Kweneng District Kweneng East 20,527 9,332 11,195 18. Letlhakane Central District Central Boteti 19,539 9,848 9,691 19. -

Public Primary Schools

PRIMARY SCHOOLS CENTRAL REGION NO SCHOOL ADDRESS LOCATION TELE PHONE REGION 1 Agosi Box 378 Bobonong 2619596 Central 2 Baipidi Box 315 Maun Makalamabedi 6868016 Central 3 Bobonong Box 48 Bobonong 2619207 Central 4 Boipuso Box 124 Palapye 4620280 Central 5 Boitshoko Bag 002B Selibe Phikwe 2600345 Central 6 Boitumelo Bag 11286 Selibe Phikwe 2600004 Central 7 Bonwapitse Box 912 Mahalapye Bonwapitse 4740037 Central 8 Borakanelo Box 168 Maunatlala 4917344 Central 9 Borolong Box 10014 Tatitown Borolong 2410060 Central 10 Borotsi Box 136 Bobonong 2619208 Central 11 Boswelakgomo Bag 0058 Selibe Phikwe 2600346 Central 12 Botshabelo Bag 001B Selibe Phikwe 2600003 Central 13 Busang I Memorial Box 47 Tsetsebye 2616144 Central 14 Chadibe Box 7 Sefhare 4640224 Central 15 Chakaloba Bag 23 Palapye 4928405 Central 16 Changate Box 77 Nkange Changate Central 17 Dagwi Box 30 Maitengwe Dagwi Central 18 Diloro Box 144 Maokatumo Diloro 4958438 Central 19 Dimajwe Box 30M Dimajwe Central 20 Dinokwane Bag RS 3 Serowe 4631473 Central 21 Dovedale Bag 5 Mahalapye Dovedale Central 22 Dukwi Box 473 Francistown Dukwi 2981258 Central 23 Etsile Majashango Box 170 Rakops Tsienyane 2975155 Central 24 Flowertown Box 14 Mahalapye 4611234 Central 25 Foley Itireleng Box 161 Tonota Foley Central 26 Frederick Maherero Box 269 Mahalapye 4610438 Central 27 Gasebalwe Box 79 Gweta 6212385 Central 28 Gobojango Box 15 Kobojango 2645346 Central 29 Gojwane Box 11 Serule Gojwane Central 30 Goo - Sekgweng Bag 29 Palapye Goo-Sekgweng 4918380 Central 31 Goo-Tau Bag 84 Palapye Goo - Tau 4950117 -

BOTSWANA Country Operational Plan 2016 Strategic Direction Summary

BOTSWANA Country Operational Plan 2016 Strategic Direction Summary May 16, 2016 Table of Contents Goal Statement 1.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context 1.1 Summary statistics, disease burden and epidemic profile 1.2 Investment profile 1.3 Sustainability Profile 1.4 Alignment of PEPFAR investments geographically to burden of disease 1.5 Stakeholder engagement 2.0 Core, near-core and non-core activities for operating cycle 3.0 Geographic and population prioritization 4.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Scale-up Locations and Populations 4.1 Targets for scale-up locations and populations 4.2 Priority population prevention 4.3 Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision (VMMC) 4.4 Preventing Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) 4.5 HIV testing and Counseling (HTC) 4.6 Facility and community-based care and support 4.7 TB/HIV 4.8 Adult treatment 4.9 Pediatric Treatment 4.10 Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) 4.11 Gender and Gender-Based Violence (GBV) 5.0 Program Activities in Sustained Support Locations and Populations 5.1 Package of services and expected volume in sustained support locations and populations 5.2 Transition plans for redirecting PEPFAR support to scale-up locations and populations 6.0 Program Support Necessary to Achieve Sustained Epidemic Control 6.1 Critical systems investments for achieving key programmatic gaps 6.2 Critical systems investments for achieving priority policies 6.3 Proposed system investments outside of programmatic gaps and priority policies 7.0 USG Management, Operations and Staffing Plan to Achieve -

CITIES/TOWNS and VILLAGES Projections 2020

CITIES/TOWNS AND VILLAGES Projections 2020 Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Tel: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Toll Free: 0800 600 200 Private Bag F193, City of Francistown Botswana Tel. 241 5848, Fax. 241 7540 Private Bag 32 Ghanzi Tel: 371 5723 Fax: 659 7506 Private Bag 47 Maun Tel: 371 5716 Fax: 686 4327 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Cities/Towns And Villages Projections 2020 Published by Statistics Botswana Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Website: www.statsbots.org.bw E-mail: [email protected] Contact: Census and Demography Analysis Unit Tel: (267) 3671300 Fax: (267) 3952201 November, 2020 COPYRIGHT RESERVED Extracts may be published if source Is duly acknowledged Cities/Towns and Villages Projections 2020 Preface This stats brief provides population projections for the year 2020. In this stats brief, the reference point of the population projections was the 2011 Population and Housing Census, in which the total population by age and sex is available. Population projections give a picture of what the future size and structure of the population by sex and age might look like. It is based on knowledge of the past trends, and, for the future, on assumptions made for three components of population change being fertility, mortality and migration. The projections are derived from mathematical formulas that use current populations and rates of growth to estimate future populations. The population projections presented is for Cities, Towns and Villages excluding associated localities for the year 2020. Generally, population projections are more accurate for large populations than for small populations and are more accurate for the near future than the distant future. -

Fermentative Microbes of Khadi, a Traditional Alcoholic Beverage of Botswana

fermentation Article Fermentative Microbes of Khadi, a Traditional Alcoholic Beverage of Botswana Koketso Motlhanka 1,*, Kebaneilwe Lebani 1, Teun Boekhout 2,3 and Nerve Zhou 1 1 Department of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Botswana International University of Science and Technology, Private Bag 16, Central District, Palapye 10071, Botswana; [email protected] (K.L.); [email protected] (N.Z.) 2 Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, 3584 CT Utrecht, The Netherlands; [email protected] 3 Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics (IBED), University of Amsterdam, 1098 SM Amsterdam, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +267-7632-5058 or +267-7427-6598 Received: 18 April 2020; Accepted: 8 May 2020; Published: 11 May 2020 Abstract: Khadi is a popular traditional alcoholic beverage in rural households in Botswana. The product is produced by fermentation of ripened sun-dried Grewia flava (Malvaceae) fruits supplemented with brown Table Sugar. Despite its popularity, its growing consumer acceptance, its potential nutritional value, and its contribution to the socio-economic lifestyle of Botswana, the production process remains non-standardized. Non-standardized production processes lead to discrepancies in product quality and safety as well as varying shelf life. Identification of unknown fermentative microorganisms of khadi is an important step towards standardization of its brewing process for entrance into commercial markets. The aim of this study was to isolate and identify bacteria and yeasts responsible for fermentation of khadi. Yeasts and bacteria harbored in 18 khadi samples from 18 brewers in central and northern Botswana were investigated using classic culture-dependent techniques and DNA sequencing methods. -

Download/ESACCI-LC-Ph2-Pugv2 2.0.Pdf (Accessed on 25 January 2020)

remote sensing Article Vegetation Trends, Drought Severity and Land Use-Land Cover Change during the Growing Season in Semi-Arid Contexts Felicia O. Akinyemi 1,2 1 Earth and Environmental Science Department, Botswana International University of Science and Technology, Private Bag 16, 10071 Palapye, Botswana; [email protected] or [email protected] 2 Institute of Geography, University of Bern, Hallerstrasse 12, CH-3012 Bern, Switzerland Abstract: Drought severity and impact assessments are necessary to effectively monitor droughts in semi-arid contexts. However, little is known about the influence land use-land cover (LULC) has—in terms of the differences in annual sizes and configurations—on drought effects. Coupling remote sensing and Geographic Information System techniques, drought evolution was assessed and mapped. During the growing season, drought severity and the effects on LULC were exam- ined and whether these differed between areas of land change and persistence. This study used areas of economic importance to Botswana as case studies. Vegetation Condition Index, derived from Normalised Difference Vegetation Index time series for the growing seasons (2000–2018 in comparison to 2020–2021), was used to assess droughts for 17 constituencies (Botswana’s fourth administrative level) in the Central District of Botswana. Further analyses by LULC types and land change highlighted the vulnerability of both human and natural systems to drought. Identified drought periods in the time series correspond to declared drought years by the Botswana government. Drought severity (extreme, severe, moderate and mild) and the percentage of land areas affected varied in both space and time. The growing seasons of 2002–2003, 2003–2004 and 2015–2016 were the most drought-stricken in the entire time series, coinciding with the El Niño southern oscillation Citation: Akinyemi, F.O. -

Urban Vs Rural Botswana

About Tutorial Glossary Documents Images Maps Google Earth Please provide feedback! Click for details You are here: Home>People and the River >Socioeconomics in the Basin >Urban vs Rural >Botswana Urban vs Rural Botswana Botswana has been an economic miracle. One of the ten poorest countries in the world at independence in 1966, it has since become a middle income country, mainly due to goodgovernance, and the discovery and mining of the world’s richest diamond fields (see alsoDistribution of Economic Activities ). Despite this success, critical economic and social challenges confront Botswana: the need to diversify the economy; ability to implement policies, programmes and projects; unemployment; poverty;vulnerability to climatic changes, and changes in the world prices of its major commodities. Within the Limpopo River basin the majority of population is considered to berural. There are six administrative districts found within the basin: North East; Central; Kgatleng; South East and parts of Kweneng. The main urban centres within the basin are Serowe, Selebi- Phikwe, Palapye, Mahalapye, Francistown, Mochudi and Gaborone (capital city) (LBPTC 2010). These cities have populations ranging from 17 362 to 39 769. There are four smaller cities, Tonota, Bobonong, Mmadinare and Masunga and several smaller settlements scattered throughout the predominantly rural region of thebasin (LBPTC 2010). Gaborone is the capital city of Botswana. Source: Hatfield 2011 ( click to enlarge ) Development Priorities and Needs Urban regions in Botswana have been the focus of development, whilerural regions are characterised by low productivity, deteriorating natural- resource bases, absolute poverty, high mortality rates and lower life expectancy. As a result, there has been migration from rural tourban areas, with the latter growing at up to 10% annually.