Revista De Investigações Constitucionais

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albanian Media and the Specifics of the Local Market

Studies in Communication Sciences 12 (2012) 49–52 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Studies in Communication Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scoms General section Albanian media and the specifics of the local market Mark Marku 1 Department of Journalism and Communication, University of Tirana, Albania article info abstract Keywords: After the fall of communism in 1991, Albanian media rode a wave of privatization, bringing with it a load Albanian media of new market entrants and a high level of disorder. As the media market began to grow and private Media diversity outlets captured larger audiences, holes appeared in Albanian media legislation, making it difficult to Media competition enforce fiscal transparency and competition amongst participants. Privatized media As a result of their market advantage, large private media companies are now outspending smaller competitors in order to boost innovation and technology. As media companies continue to grow in all major forms of Albanian media, large stations exploit the lack of government oversight to increase their advantage in advertising, programming, and technological innovation. By implementing legislation designed to stabilize growth, the diversity of Albanian media outlets will increase along with widespread advancements to technology and infrastructure. © 2012 Swiss Association of Communication and Media Research. Published by Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved. Changes to the political system in Albania are associated with the Albanian-speaking media scene. According to statistics from the the evolution and radical transformation of the media field. The National Council of Radio and Television KKRT (KKRT 2011, p. 34) establishment of both political pluralism and a market economy in in Albania today, four national television stations are in operation, 1991 brought with it the collapse of the state’s monopoly over the 65 local stations, 33 cable television stations, three national and 47 Albanian media market. -

Interim Opinion on the Draft Law on the Reform of the Supreme Court Of

Warsaw, 16 October 2019 Opinion-Nr.: JUD-MDA/358/2019 [AlC] http://www.legislationline.org/ INTERIM OPINION ON THE DRAFT LAW ON THE REFORM OF THE SUPREME COURT OF JUSTICE AND THE PROSECUTOR’S OFFICES OF THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA (AS OF SEPTEMBER 2019) based on an unofficial English translation of the Draft Law provided by the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Moldova This Opinion has benefited from contributions made by the following experts: Dr. Grzegorz Borkowski, Judge, International Legal Expert and former Head of Office of the National Council of the Judiciary of Poland; Ms. Michèle Rivet, C.M., Honorary Member and Former Vice-President of the International Commission of Jurists; Professor Andras Sajo, Central European University in Budapest and former judge and Vice-President of the European Court of Human Rights; Mr. Maarten Steenbeek, International Rule of Law Expert; and Mr. Arman Zrvandyan, International Human Rights Lawyer. The Opinion represents the position of ODIHR only and does not necessarily reflect the position of the experts. OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Ulica Miodowa 10 PL-00-251 Warsaw ph. +48 22 520 06 00 fax. +48 22 520 0605 This Opinion is also available in Romanian. However, the English version remains the only official version of the document. ODIHR Interim Opinion on the Draft Law on the Reform of the Supreme Court of Justice and the Prosecutor’s Offices of the Republic of Moldova (as of September 2019) TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................... 3 II. SCOPE OF REVIEW .................................................................................................... 3 III. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND KEY RECOMMENDATIONS ........................... -

Rule of Law in the Western Balkans: ASPEN 5 Exploring the New EU Enlargement Strategy and Necessary Steps Ahead POLICY PROGRAM

RULE OF LAW IN THE WESTERN BALKANS: EXPLORING THE NEW EU ENLARGEMENT STRATEGY AND NECESSARY STEPS AHEAD April 16-19, 2018 | Alt Madlitz In cooperation with: The Aspen Institute Germany wishes to thank the German Federal Foreign Office for its sponsorship of the Aspen Southeast Europe Program 2018 through the Stability Pact for South Eastern Europe. The mission of the Aspen Institute Germany is to improve the quality of leadership through dialog about the values and ideals essential to meeting the challenges facing organizations and governments at all levels. Over its forty-year history, Aspen Germany has been devoted to advancing values-based leadership – to creating a safe, neutral space in which leaders can meet in order to discuss the complex challenges facing modern societies confidentially and in depth, with respect for differing points of view, in a search for common ground. This reader includes conference papers and proceedings of Aspen Germany’s Western Balkans conference in 2018. The Aspen Institute’s role is limited to that of an organizer and convener. Aspen takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the U.S. or German governments. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in all Aspen publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors. For further information about the Aspen Institute Germany, please write to Aspen Institute Deutschland e.V. Friedrichstraße 60 10117 Berlin Germany or call at +49 30 80 48 90 0. Visit us at www.aspeninstitute.de www.facebook.com/AspenDeutschland www.twitter.com/AspenGermany Copyright © 2018 by The Aspen Institute Deutschland e.V. -

An Analysis of the Vetting Process in Albania

An Analysis of the Vetting Process in Albania Policy Analysis - No. 01/2017 An Analysis of the Vetting Process in Albania www.legalpoliticalstudies.org 3 An Analysis of the Vetting Process in Albania ABOUT GLPS Group for Legal and Political Studies is an independent, non-partisan and non-profit public policy organization based in Prishtina, Kosovo. Our mission is to conduct credible policy research in the fields of politics, law and economics and to push forward policy solutions that address the failures and/or tackle the problems in the said policy fields. www.legalpoliticalstudies.org 3 An Analysis of the Vetting Process in Albania Policy Analysis No. 01/2017 An Analysis of the Vetting Process in Albania Authors: *Bardha Maxhuni, **Umberto Cucchi June 2017 For their contribution, we would like to thank the external peer reviewers who provided excellent comments on earlier drafts of this policy product. GLPS internal staff provided very helpful inputs, edits and contributed with excellent research support. © Group for Legal and Political Studies, June, 2017. The opinions expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect those of Group for Legal and Political Studies donors, their staff, associates or Board(s). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any mean without the permission. Contact the administrative office of the Group for Legal and Political Studies for such requests. Group for Legal and Political Studies ‟ “Rexhep Luci str. 16/1 Prishtina 10 000, Kosovo Web-site: www.legalpoliticalstudies.org E-mail: [email protected] Tel/fax.: +381 38 234 456 *Research Fellow, Group for Legal and Political Studies ** International Research Fellow, Group for Legal and Political Studies www.legalpoliticalstudies.org 3 An Analysis of the Vetting Process in Albania This page intentionally left blank www.legalpoliticalstudies.org 3 An Analysis of the Vetting Process in Albania AN ANALYSIS OF THE VETTING PROCESS IN ALBANIA I. -

TV and On-Demand Audiovisual Services in Albania Table of Contents

TV and on-demand audiovisual services in Albania Table of Contents Description of the audiovisual market.......................................................................................... 2 Licensing authorities / Registers...................................................................................................2 Population and household equipment.......................................................................................... 2 TV channels available in the country........................................................................................... 3 TV channels established in the country..................................................................................... 10 On-demand audiovisual services available in the country......................................................... 14 On-demand audiovisual services established in the country..................................................... 15 Operators (all types of companies)............................................................................................ 15 Description of the audiovisual market The Albanian public service broadcaster, RTSH, operates a range of channels: TVSH (Shqiptar TV1) TVSH 2 (Shqiptar TV2) and TVSH Sat; and in addition a HD channel RTSH HD, and three thematic channels on music, sport and art. There are two major private operators, TV Klan and Top Channel (Top Media Group). The activity of private electronic media began without a legal framework in 1995, with the launch of the unlicensed channel Shijak TV. After -

Freedom of the Press - Albania (2011)

Page 1 of 2 Print Freedom Of The Press - Albania (2011) Status: Partly Free Legal Environment: 16 Political Environment: 17 Economic Environment: 17 Total Score: 50 The constitution guarantees freedom of the press, and the media are vigorous and fairly diverse. However, outlets often display a strong political bias, and their reporting is influenced by the economic or political interests of their owners. Libel remains a criminal offense, punishable by fines and up to two years in prison. While there have been no criminal libel cases against journalists in recent years, former culture minister Ylli Pango successfully sued the private television station Top Channel for airing hidden- camera video of him asking young female job applicants to disrobe. He had been forced to resign after the recordings were broadcast in March 2009. In June 2010, a court ordered the station to pay roughly $500,000 in damages to Pango on the grounds that they had been obtained illegally. The government of Prime Minister Sali Berisha has repeatedly used administrative mechanisms, including tax investigations and arbitrary evictions from state-owned buildings, to disrupt the operations of media outlets it perceives as hostile. Regulatory bodies are seen as highly politicized. Journalists sometimes face intimidation and assaults in response to critical reporting. Mero Baze, the owner of the newspaper Tema and host of a talk show on the independent television station Vizion Plus, was allegedly assaulted by businessman Rezart Taci and two of his bodyguards in November 2009. Through his media outlets, Baze had accused Taci of tax evasion and irregularities in his acquisition of a state-owned oil refinery. -

Print This Article

E-ISSN 2281-4612 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Vol 5 No 3 S1 ISSN 2281-3993 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy December 2016 Teachers Civic Education and Their Methodological Skills Affect Student Engagement in Civic Participation Dr. Lindita Lutaj University "Aleksander Moisiu", Faculty of Education, Department of Pedagogy, Albania Email: [email protected] Doi:10.5901/ajis.2016.v5n3s1p336 Abstract Civic education is important, because the society needs people to contribute in the most effective way. The teacher plays an important role in encouraging pupils to civic actions. The aim of this study is find out the relationship between teachers civic education and their methodological skills in students civic participation. The statistical package of social sciences (SPSS 20) was used for data analysis. Questionnaires were administered to 34 teachers who give social education subject in 6th-9th grade and 414 students of these teachers, in Durres and Elbasan. The factorial analysis of the questionnaire on teachers civic education discovered two important factors: civic responsibility and civic values, while according to teachers’ methodological skills discovered three factors: the quality of the class, learning and student assessment. It was also observed that there is a positive relationship between teachers’ civic education and their methodological skills with students’ civic participation, which it was reported by teachers or perceived by students. There is a significant statistical relationship between teachers civic education and students civic participation: r = .40 (p <0:01), which is stronger than teachers methodological skills and students civic participation: r = .28 (p <0:01). According to the findings of this study should be increased teachers training programs at local and national level. -

Important Notice

IMPORTANT NOTICE NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION IN, OR INTO, THE UNITED STATES EXCEPT TO QUALIFIED INSTITUTIONAL BUYERS (“QIBs”), AS DEFINED IN, AND IN COMPLIANCE WITH, RULE 144A UNDER THE U.S. SECURITIES ACT OF 1933, AS AMENDED (THE “SECURITIES ACT”) OR OTHERWISE THAN TO PERSONS TO WHOM IT CAN LAWFULLY BE DISTRIBUTED. IMPORTANT: You must read the following before continuing. The following applies to the Prospectus following this page, whether received by e-mail, accessed from an internet page or received as a result of electronic transmission, and you are therefore required to read this carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the Prospectus. In accessing the Prospectus, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them any time you receive any information from us as a result of such access. The Prospectus has been prepared solely in connection with the proposed offering to certain institutional and professional investors of the securities described herein, which are exempt from registration under the Securities Act. Nothing in this electronic transmission constitutes an offer of securities for sale in the United States. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES AN OFFER OF SECURITIES FOR SALE OR A SOLICITATION OF AN OFFER TO BUY SECURITIES IN ANY JURISDICTION WHERE THE OFFER, SALE OR SOLICITATION IS NOT PERMITTED. ANY SECURITIES TO BE ISSUED HAVE NOT BEEN, AND WILL NOT BE, REGISTERED UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT, OR THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION OF THE UNITED STATES, AND THE SECURITIES MAY NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD WITHIN THE UNITED STATES, EXCEPT PURSUANT TO AN EXEMPTION FROM, OR IN A TRANSACTION NOT SUBJECT TO, THE REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS OF THE SECURITIES ACT AND APPLICABLE STATE SECURITIES LAWS. -

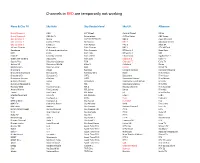

Channels in RED Are Temporarily Not Working

Channels in RED are temporarily not working Nova & Ote TV Sky Italy Sky Deutschland Sky UK Albanian Nova Cinema 1 AXN 13th Street Animal Planet 3 Plus Nova Cinema 2 AXN SciFi Boomerang At The Races ABC News Ote Cinema 1 Boing Cartoon Network BBC 1 Agon Channel Ote Cinema 2 Caccia e Pesca Discovery BBC 2 Albanian screen Ote Cinema 3 Canale 5 Film Action BBC 3 Alsat M Village Cinema Cartoonito Film Cinema BBC 4 ATV HDTurk Sundance CI Crime Investigation Film Comedy BT Sports 1 Bang Bang FOX Cielo Film Hits BT Sports 2 BBF FOXlife Comedy Central Film Select CBS Drama Big Brother 1 Greek VIP Cinema Discovery Film Star Channel 5 Club TV Sports Plus Discovery Science FOX Chelsea FC Cufo TV Action 24 Discovery World Kabel 1 Clubland Doma Motorvision Disney Junior Kika Colors Elrodi TV Discovery Dmax Nat Geo Comedy Central Explorer Shkence Discovery Showcase Eurosport 1 Nat Geo Wild Dave Film Aktion Discovery ID Eurosport 2 ORF1 Discovery Film Autor Discovery Science eXplora ORF2 Discovery History Film Drame History Channel Focus ProSieben Discovery Investigation Film Dy National Geographic Fox RTL Discovery Science Film Hits NatGeo Wild Fox Animation RTL 2 Disney Channel Film Komedi Animal Planet Fox Comedy RTL Crime Dmax Film Nje Travel Fox Crime RTL Nitro E4 Film Thriller E! Entertainment Fox Life RTL Passion Film 4 Folk+ TLC Fox Sport 1 SAT 1 Five Folklorit MTV Greece Fox Sport 2 Sky Action Five USA Fox MAD TV Gambero Rosso Sky Atlantic Gold Fox Crime MAD Hits History Sky Cinema History Channel Fox Life NOVA MAD Greekz Horror Channel Sky -

Media Në Tranzicion: Reflektim Pas Tri Dekadash Media Në Tranzicion: Refleksione Pas Tri Dekadash

MEDIA NË TRANZICION: reflektim pas tri dekadash MEDIA NË TRANZICION: REFLEKSIONE PAS TRI DEKADASH Tiranë, 2020 Media në Tranzicion: refleksione pas tri dekadash 1 Botues: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Office Tirana Rr. Kajo Karafili Nd-14, Hyrja 2, Kati 1, Kutia Postare 1418 Tiranë, Shqipëri Për realizimin e këtij studimi punoi një grup pune i përbërë nga Agim Doksani, Dorentina Hysa, Kejsi Bozo. Kopertina dhe layout: Bujar Karoshi Opinionet, gjetjet, konkluzionet dhe rekomandimet e shprehura në këtë botim janë të autorëve dhe nuk reflektojnë domosdoshmërisht ato të Fondacionit Friedrich Ebert. Publikimet e Fondacionit Friedrich Ebert nuk mund të përdoren për arsye komerciale pa miratim me shkrim. 2 Media në Tranzicion: refleksione pas tri dekadash Përmbajtja e lëndës KAPITULLI 1 30 VJET MEDIA NË TRANZICION: NJË PANORAMË HISTORIKE .................................................................................... 5 KAPITULLI 2 RRUGA E VËSHTIRË DREJT LIRISË SË MEDIAS ............................................ 29 KAPITULLI 3 SFIDAT E PROFESIONALIZMIT: MEDIA NDËRMJET BIZNESIT DHE POLITIKËS ...................................................................................... 45 Referenca ........................................................................................................................ 55 Media në Tranzicion: refleksione pas tri dekadash 3 4 Media në Tranzicion: refleksione pas tri dekadash KAPITULLI 1 30 VJET MEDIA NË TRANZICION: NJË PANORAMË HISTORIKE I. SHTYPI I SHKRUAR: NJË RRUGË ME KTHESA Një parahistori Pas një periudhe -

Lista E TV Kanaleve

Lista e TV Kanaleve Pako bazë 1 TVM Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 2 TVM 2 Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 3 TVM 3 Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 4 TVM 4 Sportiv Pako bazë HD 5 TVM 5 Fëmijë Pako bazë HD 6 Sitel Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 7 Telma Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 8 24 Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 9 Kanal 5 Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 10 KLAN MACEDONIA Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 11 Alfa TV Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 12 TV Sonce Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 13 ALSAT Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 14 SHENJA Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 15 Nasha TV Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 16 TVM Kuvendor Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 17 EDO Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 18 21TV Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 19 KOHA Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 20 Balkan Music Muzikor Pako bazë SD 21 ARTE Dokumentar Pako bazë HD 22 Game Toon Argëtues Pako bazë HD 23 Zdrava Televizija Argëtues Pako bazë SD 24 Boomerang Fëmijë Pako bazë SD 25 Cartoon Network Fëmijë Pako bazë SD 26 Jim Jam Fëmijë Pako bazë SD 27 RT Documentary HD Dokumentar Pako bazë HD 28 CNN International Informativ Pako bazë SD 29 Rai UNO Informativ Pako bazë SD 30 Rai DUO Informativ Pako bazë SD 31 TVE Informativ Pako bazë HD 32 TRT 1 Informativ Pako bazë HD 33 SAT 1 Informativ Pako bazë SD 34 RTR PLANETA Informativ Pako bazë SD 35 Russia Today Informativ Pako bazë HD 36 Russia 24 Informativ Pako bazë SD 37 RTL Informativ Pako bazë SD 38 HRT 1 Kolazh (Regjional) Pako bazë HD НЕОТЕЛ ДОО Скопје; Кузман Јосифовски Питу бр.15, 1000 Скопје, Република Северна Македонија Тел:+389 2 55 11 155; Техничка поддршка: +389 2 55 11 111 www.neotel.mk 39 HRT 3 -

The Contribution of the Venice Commission on to the Albanian Legal System Dr

International Journal of Law and Interdisciplinary Legal Studies | 5 JP1. DK15-8106 THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE VENICE COMMISSION ON TO THE ALBANIAN LEGAL SYSTEM DR. JONIDA MEHMETAJ1 ABSTRACT In their legal activity, states are often assisted by international actors to draft their legislative acts in line with international standards. One of these bodies is the Venice Commission, a Council of Europe body that, through its Opinions and legal advice, assists and supervises states in complying with the principles of democracy. The present study addresses the case of Albania and its relationship with the Commission. It seeks to identify the impact of the Opinions announced by the Commission on Albania and the issues for which it was necessary to submit a request for an Opinion. A recent case in which the Venice Commission has lent its expertise to Albania is the undertaking of a reform of the justice system. In this difficult process, the Venice Commission’s recent Opinions have served as a guide for taking appropriate steps and for adopting a reform that guarantees an efficient and impartial justice system. Key words: Opinions, Contribution, Venice Commission, Albania, Justice reform INTRODUCTION The European Commission for Democracy Through Law, otherwise known as the Venice Commission, has continuously contributed to Albania through its Opinions on legal issues. Albania’s relationship with the Venice Commission has been long-lived, since the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in 1995 expressed a favourable Opinion on Albania's application for membership in the Council of Europe (Parliamentary Assembly, 1995). The ratification of the Statute of the Council of Europe on 13 July 1995 and its entry into force on that day enabled Albania to become a member of the Council of Europe.