The Genesis of the Wind from the Stars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Checklist of George Macdonald's Books Published in America, 1855-1930

North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies Volume 39 Article 2 1-1-2020 A Checklist of George MacDonald's Books Published in America, 1855-1930 Richard I. Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind Recommended Citation Johnson, Richard I. (2020) "A Checklist of George MacDonald's Books Published in America, 1855-1930," North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies: Vol. 39 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind/vol39/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Checklist of George MacDonald Books Published in America, 1855-1930 Richard I. Johnson Many of George MacDonald’s books were published in the US as well as in the United Kingdom. Bulloch and Shaberman’s bibliographies only provide scanty details of these; the purpose of this article is to provide a more accurate and comprehensive list. Its purpose is to identify each publisher involved, the titles that each of them published, the series (where applicable) within which the title was placed, the date of publication, the number of pages, and the price. It is helpful to look at each of these in more detail. Publishers About 50 publishers were involved in publishing GMD books prior to 1930, although about half of these only published one title. -

A Read of at the Back of the North Wind

A Read��� of At the Back of the North Wind Col�� Ma�love acDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind (1871) was first serialised inM Good Words for the Young under his own editorship, from October 1868 to November 1870. It was his first attempt at writing a full-length “fairy-story” for children, following on his shorter fairy tales—including “The Selfish Giant,” “The Light Princess,” and “The Golden Key”—written between 1862 and 1867, and published in Dealings with the Fairies (1867). At the Back of the North Wind is, in fact, longer than either of the Princess books that were to follow it, The Princess and the Goblin (1872) and The Princess and Curdie (1882). It tells of the boy Diamond’s life as a cabman’s son in a poor area of mid-Victorian London, and of his meetings and adventures with a lady called North Wind; and it includes a separate fairy tale called “Little Daylight,” two dream-stories, and several poems. Generally well received by the public, it has hardly been out of print since. At the Back of the North Wind is MacDonald’s only fantasy set mainly in this world. In Phantastes (1858), Anodos goes into Fairy Land and in Lilith Mr. Vane finds himself in the Region of the Seven Dimensions. In the Princess books we are in a fairy-tale realm of kings, princesses, and goblins; and the worlds of the shorter fairy tales are all full of fairies, witches, and giants. But Diamond’s story nearly all happens either in Victorian London or in other parts of the world where North Wind takes him. -

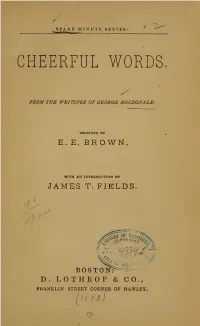

Cheerful Words. from the Writings of George Macdonald

SPARE MINUTE SERIES. CHEERFUL WORDS, FROM THE WRITINGS OF GEORGE MACDONALD. SELECTED BY E. E. BROWN WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY JAMES T. FIELDS > i '"£" BOSTON^ D. LOTHROP & CO., FRANKLIN STREET CORNER OF HAWLEY. - Oh 5? Copyright by D. LOTHROP & COMPANY. 1880. INTRODUCTION. IT must be a very remote corner of America, indeed, where the writings of George MacDonald would not only be knowrv but ardently loved. David Elginbrod, Ranald Ban- nerman. Alec Forbes, Robert Falconer, and Little Diamond have many friends by this time all over the land, and are just as real personages, thousands of miles west of New York and Boston, as they are hereabouts. Now there must be some good reason for this exceptional universality of recognition, and it is not at all difficult to discern why MacDonald's characters should be welcome guests every- where. The writer who speaks through his beautiful crea- tures of imagination, imploring us to believe that " Every human heart is human. That in even savage bosoms There are longings, yearnings, strivings For the good they comprehend not. That the feeble hands and helpless Groping blindly in the darkness 3 " 4 Introduction. Touch God's right hand in that darkness And are lifted up and strengthened — that writer, if he be a master of his art, like MacDonald, will be a light and a joy in every household, however situated. It is pleasant, always, to hold up for admiration the authors who have borne witness to the eternal beauty and cheerful capabilities of the universe around us, whatever may be our own petty sufferings or discomforts ; who con- tinually teach us that Optimism is better than Pessimism, and much more moral as a conduct of life, and are lovingly reminding us, whenever they write books or poems, of the holiness of helpfulness. -

Select Bibliography of the Works of George Macdonald

George MacDonald: A Select Bibliography This is not a comprehensive listing of MacDonald’s works. For a more complete list, please see the following: Bulloch, John Malcolm. A Bibliography of George MacDonald. 1925. Jordan, Mary Nance. George MacDonald: A Bibliographical Catalog and Record. Limited edition of 100 copies. Fairfax, VA: privately published, 1984. Shaberman, Raphael. George MacDonald: a Bibliographical Study. Winchester, Hampshire/Detroit: St. Paul's Bibliographies/Omnigraphics, 1990. FAIRY TALES & WORKS FOR CHILDREN -Dealings with the Fairies, 1867 -At the Back of the North Wind, 1871 -The Princess and the Goblin, 1872 -Gutta Percha Willie: The Working Genius, 1873 -The Wise Woman, 1875 (alternate titles: The Lost Princess and A Double Story) -The Princess and Curdie, 1883 -The Light Princess and Other Fairy Tales, 1893 -The Complete Fairy Tales, 1999 FANTASIES -Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women, 1858 -The Portent, 1864 -Works of Fancy and Imagination (10 vols), 1871 -Lilith, 1895 NON-FICTION WORKS & POETRY -Within and Without: A Dramatic Poem, 1855 -Poems, 1857 -The Disciple and Other Poems, 1867 -Unspoken Sermons, 1867 -The Miracles of Our Lord, 1870 -Exotics: A Translation of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis, the Hymn Book of Luther, and Other Poems from the German and Italian, 1876 -A Book of Strife in the Form of the Diary of an Old Soul, 1880 -A Threefold Cord: Poems by Three Friends, 1883 -The Tragedie of Hamlet, 1885 -Unspoken Sermons: Second Series, 1886 -Unspoken Sermons: Third Series, 1889 -The Hope of the Gospel, 1892 -The Poetical Works of George MacDonald - 2 vols, 1893 -A Dish of Orts, 1893 -Scotch Songs and Ballads, 1893 -Rampolli, 1897 (expanded edition of Exotics) -George Macdonald in the pulpit: the 'spoken' sermons of George Macdonald, 1996 Marion E. -

University of Dundee DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY George Macdonald

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY George MacDonald and Victorian Society Smith, Jeffrey Wayne Award date: 2013 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 GEORGE MACDONALD AND VICTORIAN SOCIETY JEFFREY WAYNE SMITH Doctor of Philosophy University of Dundee September 2013 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Declaration v Abstract vi Abbreviations vii Chapter One: Introduction 1 A Brief Guide to Reading the Thesis 3 Part 1: Critical Assessment 5 MacDonald’s Nonfiction: Writings on the Development of the Imagination and Spiritual Progression 15 Part 2: MacDonald’s Social Views and Ideas 20 MacDonald and the Nineteenth-Century Crisis of Change 20 Transitions between Town and Country in MacDonald’s Novels 28 The Ills of Industrialism in The -

75-82 4 Kihara.Indd

Use of Somnambulism in George MacDonald’s David Elginbrod Midori Kihara(木原 翠) Five years after Phantastes (1858), George MacDonald published a novel, David Elginbrod (1863). Although Phantastes and Lilith (1895) are usually seen as the major MacDonald texts since they are entirely written in standard English and have unique visionary quality, it is worth paying more attention to some of the neglected semi-realist ones, as they share similar themes and characterizations with the better- known works. David Elginbrod is considered his first attempt at a long realistic novel, one of the most dominant styles in the mid-Victorian period. MacDonald started his writing career as a poet with a narrative poem Within and Without (1855), but he later turned to the novel in order to meet the commercial demands of the mid-Victorian literary market. David Elginbrod is also categorised as MacDonald’s first Scottish novel in which he abundantly uses a North-Eastern Scottish dialect in the first section ‘Turriepuffit’, within a distinctively a Scottish country setting. However, the narrative form of David Elginbrod is peculiar, with a combination of Kailyardism (depicting a peaceful Scottish country life), gothic, and mystery elements.1 One of the most important motifs which sustains interest in the novel is ‘somnambulism’, which afflicts the anti-heroine, Euphrasia Cameron (Euphra), who appears in the second section ‘Arnstead’, set in England, and seduces the protagonist Hugh Sutherland. OED defines ‘somnambulism’ as ‘the fact or habit of walking about and performing other actions while asleep; sleep-walking’, and one derivative is ‘somnambulation’. Nouns which mean a person who walks when sleeping are ‘somnambulist’, ‘somnambular’, or ‘somnambule’. -

Ginger Stelle Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository A SWIPE AT THE DRAGON OF THE COMMONPLACE: A RE-EVALUATION OF GEORGE MACDONALD'S FICTION Ginger Stelle A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1974 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence A SWIPE AT THE DRAGON OF THE COMMONPLACE: A RE-EVALUATION OF GEORGE MACDONALD’S FICTION Ginger Stelle Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. of the University of St. Andrews 27 May 2011 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Ginger Stelle, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2008 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D in September, 2009; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2008 and 2011. Date 27 May 2011 signature of candidate............................................................. 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I, Christopher MacLachlan, hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

George Macdonald Timeline

George MacDonald: a Bio-Bibliographical Timeline DECEMBER 10, 1824 George MacDonald born in Huntly, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. 1826 Family moves to the Farm, Huntly. 1832 Death of MacDonald's mother, Helen MacKay MacDonald. 1839 George MacDonald’s father remarries Margaret McColl. 1840 Enters King's College, Aberdeen. Studies math, languages, chemistry. 1845 Awarded M.A. King's College. 1848 Attends Highbury Theological College, London; proposes to Louisa Powell. 1850 Theological degree from Highbury, accepts pastorate at Trinity Congregational Church in Arundel, Sussex. 1851 Marries Louisa Powell on March 8; ordained to Congregational ministry; Gifts privately printed translation of Twelve of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis to friends on Christmas Day. 1852 Birth of first child, Lilia Scott on January 4; congregation reduces his salary in June. 1853 Resigns pastorate at Arundel, Mary Josephine born on July 23; the family moves to Manchester, MacDonald supports his family by lecturing, writing, teaching, editing a children's magazine, and gifts from friends. 1854 Daughter Caroline Grace born on September 16. 1855 Publishes Within and Without: A Dramatic Poem (Longmans). 1856 Greville born on January 20, Lady Byron becomes MacDonald's patron; the family vacations in Algiers. 1857 Irene born on August 31. MacDonalds settle in Hastings at Huntly cottage. Publishes Poems, (Longmans). 1858 MacDonald's brother John dies in June. His father dies in August. Phantastes published (Smith, Elder). Winifrid Louisa born, 6th November. First meeting with Lewis Carroll. 1859 Moves to London. MacDonald accepts professorship of English Literature at Bedford College in October. 1860 Lady Byron dies. Ronald born on October 27. Publishes The Portent (serialized anonymously) in The Cornhill Magazine with an illustration by W. -

George Macdonald and Lewis Carroll

George MacDonald and Lewis Carroll R.B. Shaberman I. Friendshipl n October, 1856, the MacDonald family went to Algiers. The visit wasI undertaken for health reasons—George MacDonald suffered from bronchial ailments—and was made possible by the generosity of Lady Byron, who had been much impressed by MacDonald’s first published book, Within and Without, a drama in blank verse which appeared in 1855. On their return in April 1857, the family moved to Hastings, and took up residence in a house in the then unfashionable Tackleway, near All Saints. A glimpse into the MacDonald’s home at this time was recorded by a visitor: I was delightfully received by a strikingly handsome young man and a most kind lady, who made me feel at once at home. There were five children at that time, all beautifully behaved and going about the house without troubling anyone. On getting better acquainted with the family, I was much struck by the way in which they carried on their lives with one another. At a certain time in the afternoon, you would, on going up stairs to the drawing room, see on the floor several bundles—each one containing a child! On being spoken to they said, so happily and peacefully, “We are resting,” that the intruder felt she must immediately disappear. The nurse was with them. One word from the father or mother was sufficient to bring instant attention . In the evenings, when the children were all in bed, Mr. MacDonald would still be writing in his study— ”Phantastes” it was—and Mrs. -

Refiguring George Macdonald: Science and the Realist Novel Karl Hoenzsch [email protected]

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Spring 5-16-2015 Refiguring George MacDonald: Science and the Realist Novel Karl Hoenzsch [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Hoenzsch, Karl, "Refiguring George MacDonald: Science and the Realist Novel" (2015). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2071. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2071 REFIGURING GEORGE MACDONALD: SCIENCE AND THE REALIST NOVEL Karl Hoenzsch Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Department of English, Seton Hall University May 2015 © Copyright by Karl Richard Hoenzsch 2015 All Rights Reserved ________________________ Jonathan Farina,Thesis Mentor ________________________ Nancy Enright, Second Reader Introduction Less than a year after George MacDonald’s death in 1905, Joseph Johnson published the first biography of MacDonald. Johnson’s biography dwells on MacDonald’s role as a novelist, which reveals his immediate posthumous legacy. This reception has shifted. Over the past three decades, MacDonald has been described as an explicitly Christian author while much of the criticism about MacDonald emphasizes his role as a fairy tale author and theologian. In response to the pigeonholing of MacDonald, my thesis aims to reposition his writings within the history of the realist novel through their engagement with science. Why did George MacDonald jump off the radar? Why is MacDonald not studied as much today? One possibility is his overt Scottishness. His heavy use of dialect simply makes him hard to read, but the investment is fully worth the struggle and timely, given the attention to Scotland and Celtic figures in the past twenty years. -

Bibliography of Books by and About George Macdonald (Abridged by Paul F

Bibliography of Books by and about George MacDonald (abridged by Paul F. Ford) from The Harmony Within: The Spiritual Vision of George MacDonald by Rolland Hein (Chicago: Cornerstone Press, 1999) ISBN 0-940895-43-9 Published by Cornerstone Press Chicago, 939 W. Wilson Ave., Chicago, IL 60640 www.cornerstonepress.com [email protected] See John Malcolm Bulloch’s “Bibliography of George MacDonald,” Aberdeen: The University Press; 1925), for extensive information. It is reprinted in Mary Nance Jordan, George MacDonald: A Bibliographical Catalog and Record (Privately published for the Marion E. Wade Collection, Wheaton College, Wheaton, Ill., in Fairfax, Vir., 1984). The following titles have been reprinted in facsimile editions by Johannesen Printing and Publishing, Whitethorn, Calif, 95589 [[email protected]]. The second date is that of the most recent printings. Adela Cathcart. [contains many fairy tales, parables, and poems] London: Hurst & Blackett, 1864; 1994. Alec Forbes of Howglen. London: Hurst & Blackett, 1865; 1995 Annals of a Quiet Neighbourbood. London: Hurst & Blackett, 1867; 1995. At the Back of the North Wind. London: Strahan, 1871; 1998. Castle Warlock. (More often titled Warlock O’Glenwarlock.) London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1882; 1998. David Elginbrod. London: Hurst & Blackett, 1863; 1995. A Dish of Orts. London: Sampson Low, Marston, & Co. 1893 Donal Grant. London: Kegan Paul, 1883; 1998. The Elect Lady. London: Kegan Paul, 1888; 1996. England’s Antiphon. London: Macmillan & Co., 1868; 1996. Guild Court. London: Hurst & Blackett, 1868; 1992. Gutta Percha Willie: The Working Genius. London: Henry S. King & Co., 1873; 1993. Heather and Snow. London: Chatto & Windus, 1893; 1996. -

The Genesis of George Macdonald's Scottish Novels: Edelweiss Amid the Heather? Jamie Rankin

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 6 1989 The Genesis of George MacDonald's Scottish Novels: Edelweiss Amid the Heather? Jamie Rankin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rankin, Jamie (1989) "The Genesis of George MacDonald's Scottish Novels: Edelweiss Amid the Heather?," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 24: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol24/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jamie Rankin The Genesis of George MacDonald's Scottish Novels: Edelweiss Amid the Heather? As novels go, it reveals a rare attraction to hearth and home: the plot emerges within a richly illustrated vision of country life and custom, with each simple meal, each homespun witticism, each ploughing of the fertile earth breathing deeply of country air. Its characters, true to life, range from the eccentric to the humdrum, from the deceitful and avaricious to the simple-hearted and virtuous. The narrator evokes them with the same telling eye for detail that renders the lavish depictions of the countryside so convincing and immediate. Indeed, the plot itself becomes almost inci dental to the setting. When the action does assert itself into the fore ground, it provides cameo performances of the pleasures and hardships of rural life, of family loyalties and moral choices, against a backdrop of fields, farmsteads, and ever-changing skies.