Books and Libraries in the Fiction of George Macdonald Daniel Boice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Checklist of George Macdonald's Books Published in America, 1855-1930

North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies Volume 39 Article 2 1-1-2020 A Checklist of George MacDonald's Books Published in America, 1855-1930 Richard I. Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind Recommended Citation Johnson, Richard I. (2020) "A Checklist of George MacDonald's Books Published in America, 1855-1930," North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies: Vol. 39 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind/vol39/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Checklist of George MacDonald Books Published in America, 1855-1930 Richard I. Johnson Many of George MacDonald’s books were published in the US as well as in the United Kingdom. Bulloch and Shaberman’s bibliographies only provide scanty details of these; the purpose of this article is to provide a more accurate and comprehensive list. Its purpose is to identify each publisher involved, the titles that each of them published, the series (where applicable) within which the title was placed, the date of publication, the number of pages, and the price. It is helpful to look at each of these in more detail. Publishers About 50 publishers were involved in publishing GMD books prior to 1930, although about half of these only published one title. -

Memorial Review of “George Macdonald: a Study of Two Novels.” by William Webb, Part of Volume 11 of Romantic Reassessment

Memorial review of “George MacDonald: A Study of Two Novels.” by William Webb, part of volume 11 of Romantic Reassessment. Salzburg, 1973. Deirdre Hayward illiam Webb’s aim in this study is to examine two “rather neglected”W novels of George MacDonald in order to bring out “what is most characteristic in them of the author’s undoubted genius” (105). He sets out to demonstrate that Mary Marston is “a capable piece of fiction” (58), and his discussion of Home Again, though brief, brings out several interesting features of the novel. I have chosen to comment on aspects of his study which give the reader fresh insights, and illuminate less well-known areas of MacDonald’s writing. The study itself is rather loosely structured, with the plan and links between the topics not always clear; and it is frustrating that Webb almost never gives sources for the many quoted passages, and often drops in references—for example a comparison with Dickens in Hard Times or Our Mutual Friend—without any supporting detail to contextualise his comments. Having said this, I found myself impressed by many of the issues discussed, and interested in the directions (sometimes quite obscure and fascinating) in which he points the reader. Additionally, his exploration of some of the literary sources and artistic relationships recognisable in Mary Marston contribute with some authority to MacDonald scholarship. Webb recognises the influence of seventeenth-century English literature on Mary Marston (1881), and observes that in chapter 11, “William Marston,” where Mary’s father, the saintly William Marston, dies, the theme of poetry is related to the plot (83). -

A Read of at the Back of the North Wind

A Read��� of At the Back of the North Wind Col�� Ma�love acDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind (1871) was first serialised inM Good Words for the Young under his own editorship, from October 1868 to November 1870. It was his first attempt at writing a full-length “fairy-story” for children, following on his shorter fairy tales—including “The Selfish Giant,” “The Light Princess,” and “The Golden Key”—written between 1862 and 1867, and published in Dealings with the Fairies (1867). At the Back of the North Wind is, in fact, longer than either of the Princess books that were to follow it, The Princess and the Goblin (1872) and The Princess and Curdie (1882). It tells of the boy Diamond’s life as a cabman’s son in a poor area of mid-Victorian London, and of his meetings and adventures with a lady called North Wind; and it includes a separate fairy tale called “Little Daylight,” two dream-stories, and several poems. Generally well received by the public, it has hardly been out of print since. At the Back of the North Wind is MacDonald’s only fantasy set mainly in this world. In Phantastes (1858), Anodos goes into Fairy Land and in Lilith Mr. Vane finds himself in the Region of the Seven Dimensions. In the Princess books we are in a fairy-tale realm of kings, princesses, and goblins; and the worlds of the shorter fairy tales are all full of fairies, witches, and giants. But Diamond’s story nearly all happens either in Victorian London or in other parts of the world where North Wind takes him. -

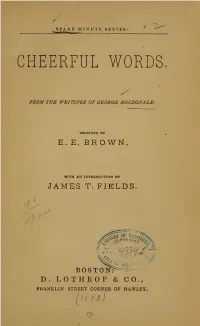

Cheerful Words. from the Writings of George Macdonald

SPARE MINUTE SERIES. CHEERFUL WORDS, FROM THE WRITINGS OF GEORGE MACDONALD. SELECTED BY E. E. BROWN WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY JAMES T. FIELDS > i '"£" BOSTON^ D. LOTHROP & CO., FRANKLIN STREET CORNER OF HAWLEY. - Oh 5? Copyright by D. LOTHROP & COMPANY. 1880. INTRODUCTION. IT must be a very remote corner of America, indeed, where the writings of George MacDonald would not only be knowrv but ardently loved. David Elginbrod, Ranald Ban- nerman. Alec Forbes, Robert Falconer, and Little Diamond have many friends by this time all over the land, and are just as real personages, thousands of miles west of New York and Boston, as they are hereabouts. Now there must be some good reason for this exceptional universality of recognition, and it is not at all difficult to discern why MacDonald's characters should be welcome guests every- where. The writer who speaks through his beautiful crea- tures of imagination, imploring us to believe that " Every human heart is human. That in even savage bosoms There are longings, yearnings, strivings For the good they comprehend not. That the feeble hands and helpless Groping blindly in the darkness 3 " 4 Introduction. Touch God's right hand in that darkness And are lifted up and strengthened — that writer, if he be a master of his art, like MacDonald, will be a light and a joy in every household, however situated. It is pleasant, always, to hold up for admiration the authors who have borne witness to the eternal beauty and cheerful capabilities of the universe around us, whatever may be our own petty sufferings or discomforts ; who con- tinually teach us that Optimism is better than Pessimism, and much more moral as a conduct of life, and are lovingly reminding us, whenever they write books or poems, of the holiness of helpfulness. -

The Genesis of the Wind from the Stars

The Genesis of The Wind From The Stars Gordon Reid y knowledge of George MacDonald began in boyhood and grew graduallyM over the years. The first books of his that I read wereThe Princess and the Goblin and The Princess and Curdie, both gifts from my grandmother. The next meeting with MacDonald was mediated by C. S. Lewis’s 1946 Anthology, which I came across when I was an undergraduate at Oxford. Oddly enough, while I found MacDonald’s thoughts stimulating, and copied several into my book of favourite quotations, nevertheless I was not impelled to go and read MacDonald’s works. Of course, at that time I did have many other things to read if I wanted a degree. At any rate, it was not until I was rector of an Edinburgh parish of the Scottish Episcopal Church that I began to read MacDonald’s works. One of my parishioners, Marion Lockhead, gave me David Elginbrod. She was herself a writer who loved George MacDonald: she used to maintain that he ought to be included in any modern Calendar of Saints (her other main candidate for this honour was Dr Johnson). What appealed to Marion about MacDonald was his ability to describe real goodness and to make it interesting and attractive. As a Scot, she also revelled in the dialogue of the characters in MacDonald’s Scottish novels. In this Anthology I have included two of David Elginbrod’s prayers— when read aloud they are magnificent. Encouraged by Marion I read many of MacDonald’s novels, some of the poetry, and both Phantastes and Lilith. -

Select Bibliography of the Works of George Macdonald

George MacDonald: A Select Bibliography This is not a comprehensive listing of MacDonald’s works. For a more complete list, please see the following: Bulloch, John Malcolm. A Bibliography of George MacDonald. 1925. Jordan, Mary Nance. George MacDonald: A Bibliographical Catalog and Record. Limited edition of 100 copies. Fairfax, VA: privately published, 1984. Shaberman, Raphael. George MacDonald: a Bibliographical Study. Winchester, Hampshire/Detroit: St. Paul's Bibliographies/Omnigraphics, 1990. FAIRY TALES & WORKS FOR CHILDREN -Dealings with the Fairies, 1867 -At the Back of the North Wind, 1871 -The Princess and the Goblin, 1872 -Gutta Percha Willie: The Working Genius, 1873 -The Wise Woman, 1875 (alternate titles: The Lost Princess and A Double Story) -The Princess and Curdie, 1883 -The Light Princess and Other Fairy Tales, 1893 -The Complete Fairy Tales, 1999 FANTASIES -Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women, 1858 -The Portent, 1864 -Works of Fancy and Imagination (10 vols), 1871 -Lilith, 1895 NON-FICTION WORKS & POETRY -Within and Without: A Dramatic Poem, 1855 -Poems, 1857 -The Disciple and Other Poems, 1867 -Unspoken Sermons, 1867 -The Miracles of Our Lord, 1870 -Exotics: A Translation of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis, the Hymn Book of Luther, and Other Poems from the German and Italian, 1876 -A Book of Strife in the Form of the Diary of an Old Soul, 1880 -A Threefold Cord: Poems by Three Friends, 1883 -The Tragedie of Hamlet, 1885 -Unspoken Sermons: Second Series, 1886 -Unspoken Sermons: Third Series, 1889 -The Hope of the Gospel, 1892 -The Poetical Works of George MacDonald - 2 vols, 1893 -A Dish of Orts, 1893 -Scotch Songs and Ballads, 1893 -Rampolli, 1897 (expanded edition of Exotics) -George Macdonald in the pulpit: the 'spoken' sermons of George Macdonald, 1996 Marion E. -

George Macdonald Poet and Theologian

1 George MacDonald Poet and Theologian MacDonald is primarily a theological thinker and writer. This seems surprising to many as he is mostly known today for his fiction and fairy- tales and his influence on the famous Inklings, especially C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien. This book explores MacDonald’s theological rationale for writing Christian fiction, arguing that it is precisely in his less overt theological works of fiction that one finds some of his most profound thinking on the lived dimension of Christian faith. When MacDonald has been considered as a serious theologian (as is the case in two of the most recent important works on MacDonald), his theology, and espe- cially his theological understanding of the imagination, is not brought to bear upon his intentional creation of Christian fiction for expressing his theology.1 Only whenSAMPLE one considers both the form and the content of his works of fiction as theology does one come to a deeper understanding of his particular theology, a theology that aims at the participation and transformation of his literary audience. Many went before MacDonald and shaped him in profound ways, but the greatest influence upon MacDonald always remained Scripture. His imaginative engagement with the world, Scripture, and literature made him a unique voice within 1. It was Kerry Dearborn’s groundbreaking doctorial dissertation that ushered in a new era in MacDonald scholarship from a theological perspective. See Dearborn, “Prophetic or Heretic.” Her published work focuses on the theological importance of the imagination: Dearborn, Baptized Imagination. Thomas Gerold’s published PhD dissertation focuses on MacDonald’s theological anthropology. -

Letter to the Editor—The George Macdonald Industry: a “Wolff” in Sheep’S Clothing?

Letter to the Editor—The George MacDonald Industry: A “Wolff” in Sheep’s Clothing? John Pennington t’s not uncommon today for us to speak, somewhat cynically, of the ShakespeareI Industry, the Eliot Industry, the Joyce Industry: those authors who have merited so much output from the critics’ assembly-line that they have become a criticism industry. Other authors such as C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and Charles Williams are also part of this industry, but they are also very popular with the mass-reader. As a result their works are packaged and repackaged to entice yet more readers. More recently another author has joined the ranks of the Inklings, a precursor and influence on these men. I’m referring of course to George MacDonald. And much of this renewed interest has created some very good MacDonald products. Eerdmans publishes handsome editions of Phantastes, Lilith, and a four-book series of MacDonald’s fantasy stories. They also publish the mass-market but useful study on MacDonald, Rolland Hein’s The Harmony Within (1982). Puffin has editions of the Curdie books and At the Back of the North Wind. Schocken has The Complete Fairy Tales of George MacDonald. Signet Classics has just come out with an edition of At the Back of the North Wind, with a succinct yet insightful afterword by Michael Patrick Hearn. Under the editorship of Hein, Shaw Publishers have compiled Mac Donald’s sermons, Collier has seen fit to reprint Lewis’s anthology on MacDonald, and Augsburg publishes the Diary of an Old Soul. Better yet, there are two scholarly journals devoted mainly to MacDonald. -

University of Dundee DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY George Macdonald

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY George MacDonald and Victorian Society Smith, Jeffrey Wayne Award date: 2013 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 GEORGE MACDONALD AND VICTORIAN SOCIETY JEFFREY WAYNE SMITH Doctor of Philosophy University of Dundee September 2013 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Declaration v Abstract vi Abbreviations vii Chapter One: Introduction 1 A Brief Guide to Reading the Thesis 3 Part 1: Critical Assessment 5 MacDonald’s Nonfiction: Writings on the Development of the Imagination and Spiritual Progression 15 Part 2: MacDonald’s Social Views and Ideas 20 MacDonald and the Nineteenth-Century Crisis of Change 20 Transitions between Town and Country in MacDonald’s Novels 28 The Ills of Industrialism in The -

Alec Forbes of Howglen: a Novel Online

Y7Pp3 [Mobile book] Alec Forbes of Howglen: A Novel Online [Y7Pp3.ebook] Alec Forbes of Howglen: A Novel Pdf Free George MacDonald ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Ingramcontent 2015-08-08Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.21 x .44 x 6.14l, .93 #File Name: 1297554078174 pagesAlec Forbes of Howglen | File size: 50.Mb George MacDonald : Alec Forbes of Howglen: A Novel before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Alec Forbes of Howglen: A Novel: 3 of 3 people found the following review helpful. Salve for a soulBy Andrea C.Any novel I've ever undertaken to read authored by George MacDonald has been a pleasure enjoyed in a way other books cannot attain. The depth of the relationships among characters and their quest to find God and His purposes are so much to learn from and live by and model oneself after. I must say Alec Forbes is no exception. Many of the characters develop in such a way, over the course of the book, that points the reader in hopeful directions and faithful thoughts. Plots are not the source of treasure,though the pages are continually turning.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. ... MacDonald's Alec Forbes of Howglen is one of his best.By Marge ForsterGeorge MacDonald's Alec Forbes of Howglen is one of his best.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Wonderful; one of his best!By dreampigHard to beat David Elginbrod, but this is a beautiful story. -

George Macdonald: a Centennial Appreciation

Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 5 Winter 1-15-1970 At the Back of the North Wind: George MacDonald: A Centennial Appreciation Glenn E. Sadler Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/tolkien_journal Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Sadler, Glenn E. (1970) "At the Back of the North Wind: George MacDonald: A Centennial Appreciation," Tolkien Journal: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/tolkien_journal/vol4/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tolkien Journal by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract A brief overview of MacDonald’s life and writing, with a particular focus on At the Back of the North Wind. Additional Keywords MacDonald, George—Influence on fantasy This article is available in Tolkien Journal: https://dc.swosu.edu/tolkien_journal/vol4/iss1/5 Sadler: At the Back of the North Wind: George MacDonald: A Centennial App Jit IhcBack of the Itorth Ifindx Cjeorye 7J!acJ)onald: JA Centennial Appreciation By (jienn C. Sadler Author of twenty-five novels, three adult prose fantasies, of fairytales, seed their imagination most with vivid— and not poems like "Baby" ("Where did you come from, baby dear?"), and always pleasant— recollections of the family circle. -

Introduction

Introduction eorge MacDonald’s fairy tales have been children’s classics since they Gfirst appeared between 1867 and 1882. They include the stories in Dealings with the Fairies (1867) and the book-length fantasies At the Back of the North Wind (1870), The Princess and the Goblin(1872), The Wise Woman (1875), and The Princess and Curdie (1882). All of them are written for children, and have children as their central characters. In these stories MacDonald created a unique blend of fantasy and realism, and a peculiar depth of mystical vision, inviting us to see our world as continually pene- trated by divine forces. Born in 1824 and raised in Huntly, Aberdeenshire, MacDonald grad- uated MA in Natural Philosophy (Science) from Aberdeen University in 1845. Though he hadSAMPLE hoped to continue his scientific studies abroad, the limitations of family finance drove him to London and a series of tutoring jobs. It was in London that his Christian faith developed as it had not dur- ing his repressive Calvinist upbringing. He trained as a Congregationalist in London, and entered on the ministry at Arundel, Sussex in 1851. In the meantime he had met and married Louisa Powell, who was to bear him eleven children and to care for him throughout his lifetime of frequently near-fatal tubercular disease. MacDonald’s life as a minister did not last long. He was expelled in 1853 by the officious officials of his church, who did not like his frequent criticisms of bourgeois greed and materialism, and resented his liberal “German theology” which suggested, for example, that heathens might be 1 © 2020 Lutterworth Press George MacDonald’s Children’s Fantasies and the Divine Imagination saved and animals go to heaven.