Sumerian and Babylonian Psalms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bismya; Or the Lost City of Adab : a Story of Adventure, of Exploration

The Lost City of Adab 1 ' i %|,| / ";'M^"|('1j*)'| | Edgar James Banks l (Stanttll Wttfrmttg |fitag BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcm-ij W. Sage 1891 fjjRmf... Lifoi/jL 3777 Cornell University Library DS 70.S.B5B21 Bismya: or The lost city of Adab 3 1924 028 551 913 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028551913 The Author as an Arab. Bismya or The Lost City of Adab A Story of Adventure, of Exploration, and of Excavation among the Ruins of the Oldest of the Buried Cities of Babylonia By Edgar James Banks, Ph.D. Field Director of the Expedition of the Oriental Exploration Fund of the University of Chicago to Babylonia With 174 Illustrations G. P. Putnam's Sons New York and London Gbe IRnfcfeerbocfter press 1912 t.v. Copyright, 1912 BY EDGAR JAMES BANKS Ube TKniefeerbocftei: ipresg, mew ffiorft The University of Chicago office of the president Chicago, June 12, 1912. On the recommendation of the Director of the Baby- lonian Section of the Oriental Exploration Fund of the University of Chicago, permission has been granted to Dr. Edgar J. Banks, Field Director of the Fund at Bismya, to publish this account of his work in Mesopotamia. Dr. Banks was granted full authority in the field. He is entitled therefore to the credit for successes therein, as of course he will receive whatever criticism scholars may see fit to make. -

The Lost Book of Enki.Pdf

L0ST BOOK °f6NK1 ZECHARIA SITCHIN author of The 12th Planet • . FICTION/MYTHOLOGY $24.00 TH6 LOST BOOK OF 6NK! Will the past become our future? Is humankind destined to repeat the events that occurred on another planet, far away from Earth? Zecharia Sitchin’s bestselling series, The Earth Chronicles, provided humanity’s side of the story—as recorded on ancient clay tablets and other Sumerian artifacts—concerning our origins at the hands of the Anunnaki, “those who from heaven to earth came.” In The Lost Book of Enki, we can view this saga from a dif- ferent perspective through this richly con- ceived autobiographical account of Lord Enki, an Anunnaki god, who tells the story of these extraterrestrials’ arrival on Earth from the 12th planet, Nibiru. The object of their colonization: gold to replenish the dying atmosphere of their home planet. Finding this precious metal results in the Anunnaki creation of homo sapiens—the human race—to mine this important resource. In his previous works, Sitchin com- piled the complete story of the Anunnaki ’s impact on human civilization in peacetime and in war from the frag- ments scattered throughout Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Hittite, Egyptian, Canaanite, and Hebrew sources- —the “myths” of all ancient peoples in the old world as well as the new. Missing from these accounts, however, was the perspective of the Anunnaki themselves What was life like on their own planet? What motives propelled them to settle on Earth—and what drove them from their new home? Convinced of the existence of a now lost book that formed the basis of THE lost book of ENKI MFMOHCS XND PKjOPHeCieS OF XN eXTfCXUfCWJTWXL COD 2.6CHXPJA SITCHIN Bear & Company Rochester, Vermont — Bear & Company One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.InnerTraditions.com Copyright © 2002 by Zecharia Sitchin All rights reserved. -

Your Android Tablet out of Date? Our Tablets Are 4000 Years Old! by Darlene F

Your Android tablet out of date? Our tablets are 4000 years old! By Darlene F. Lizarraga This is Part Two of a developing 4-part series titled, “Digging in Storage,” documenting the results of an independent study course, directed by Dr. Irene Bald Romano, fall 2013. Some among the younger generations might be surprised to know that tablets existed long before Apple and Microsoft created the high- definition, flat-screened versions so ubiquitous today. ASM object #68 is a 4000-year-old cuneiform tablet from ancient Sumer. This type of tablet, in its day, was equally high tech and equally ubiquitous. People living in ancient Mesopotamia—the area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers comprised of the empires of Assyria, Babylonia, Sumer, and often referred to as the “Cradle of Western Civilization”—developed one of the world’s earliest writing systems around 3100 BCE. ASM #68: Cuneiform Tablet Sumerian, Ur III period, 2056 BCE Tell Jokha, Iraq; ancient Umma, Mesopotamia Mesopotamian scribes recorded daily events, Baked clay trade, astronomy, literature, and even Height 3.58 inches (9.1 cm.) Width 2.04 inches (5.2 cm.) personal correspondence with wedge-shaped Thickness 0.91 inches (2.3 cm.) symbols known as cuneiform (Latin: cuneus = Purchased from Edgar J. Banks, 1914 wedge) on tablets of soft clay which, after being inscribed, were either sun-dried or kiln COME SEE THIS TABLET AND OTHER OLD baked. The writing utensil was probably reed, WORLD OBJECTS! ASM #68 and other highlights from ASM’s Near which could have either a pointed end or a Eastern, Egyptian, Greek, Etruscan, and Roman squared-off end, and would be used either to collections will be on display in the museum’s scratch or press in order to produce the script. -

Asher-Greve / Westenholz Goddesses in Context ORBIS BIBLICUS ET ORIENTALIS

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources Asher-Greve, Julia M ; Westenholz, Joan Goodnick Abstract: Goddesses in Context examines from different perspectives some of the most challenging themes in Mesopotamian religion such as gender switch of deities and changes of the status, roles and functions of goddesses. The authors incorporate recent scholarship from various disciplines into their analysis of textual and visual sources, representations in diverse media, theological strategies, typologies, and the place of image in religion and cult over a span of three millennia. Different types of syncretism (fusion, fission, mutation) resulted in transformation and homogenization of goddesses’ roles and functions. The processes of syncretism (a useful heuristic tool for studying the evolution of religions and the attendant political and social changes) and gender switch were facilitated by the fluidity of personality due to multiple or similar divine roles and functions. Few goddesses kept their identity throughout the millennia. Individuality is rare in the iconography of goddesses while visual emphasis is on repetition of generic divine figures (hieros typos) in order to retain recognizability of divinity, where femininity is of secondary significance. The book demonstrates that goddesses were never marginalized or extrinsic and thattheir continuous presence in texts, cult images, rituals, and worship throughout Mesopotamian history is testimony to their powerful numinous impact. This richly illustrated book is the first in-depth analysis of goddesses and the changes they underwent from the earliest visual and textual evidence around 3000 BCE to the end of ancient Mesopotamian civilization in the Seleucid period. -

Sumerian Liturgical Texts

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM PUBLICATIONS OF THE BABYLONIAN SECTION VOL. X No. 2 SUMERIAN LITURGICAL TEXTS BY g600@T STEPHEN LANGDON ,.!, ' PHILADELPHIA PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM 1917 DIVINITY LIBRARY gJ-37 . f's- ". /o, ,7'Y,.'j' CONTENTS INTRODUC1'ION ................................... SUMERIAN LITURGICAL TEXTS: EPICALPOEM ON THE ORIGINOF SLIMERIANCIVILI- ZATION ...................................... LAMENTATIONTO ARURU......................... PENITENTIALPSALM TO GOD AMURRU............. LAMENTATIONON THE INVASION BY GUTIUM....... LEGENDOF GILGAMISH........................... LITURGICALHYMN TO UR-ENGUR............. .. .. LITURGICALHYMN TO DUNGI...................... LITURGICALHYMN TO LIBIT-ISHTAR(?)OR ISHME- DAGAN(?)................................... LITURGICALHYMN TO ISHME-DAGAN............... LAMENTATIONON THE DESTRUCTIONOF UR ........ HYMNOF SAMSUILUNA........................... LITURGYTO ENLIL.babbar-ri babbar.ri.gim. INCLUD- ING A TRANSLATIONOF SBH 39 .............. FRAGMENTFROM THE TITULARLITANY OF A LITURGY LITURGICALHYMN TO ISHME.DAGAN............... LITURGYTO INNINI ............................... INTRODUCTION Under the title SUMERIANLITURGICAL TEXTS the author has collected the material of the Nippur collection which belonged to the various public song services of the Sumerian and Babylonian temples. In this category he has included the epical and theological poems called lag-sal. These long epical compositions are the work of a group of scholars at Nippur who ambitiously planned to write a series -

Khafaje and Tell Asmar

Khafaje and Tell Asmar East of Baghdad, across the Tigris, in the plains watered by the Diala, where the highways of Elam, Persia and Assyria meet, new excavations were opened in 1930 by the Oriental Institute of Chicago under the direction of Prof. Henri Frankfort at Tell Asmar and at Khafaje. The first was the old city of Eshnunna, identified by the French consul H. Pognon in 1892. Both sites had become a mine for antiquities dealers of Bagh- dad. The Oriental Institute inaugurated more scientific methods, with brilliant results, continuing the excavations until 1937. Two more sites, Ischali and Tell Agrab were included in the Mesopotamian field, and still another expedition resumed the excavation of Khorsabad in Assyria, untouched since the days of Botta, Flandrin and Place. The monumental remains of the palace of Sargon are now in the Chicago Museum. In southern Mesopotamia the University of Chicago, thanks to a generous donation of Mr. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (the Oriental Expedition Fund) in 1903, opened its first excavation at Bismaja (Adab) east of Fara, under the direction of Edgar James Banks. After the First World War, improved methods and the experience gained at Kish, Ur and Uruk, contributed to the success of the Diala expedition. Level after level was exposed down to the virgin soil or at least to the water level, in historical sequence. Each main level borrows its name from the temple then existing: the Single, the Square, the Archaic Temple at Tell Asmar; again, the Re- cent, the Middle, the First Oval Temple, the First, the Second Sin Tem- ple, etc., at Khafaje. -

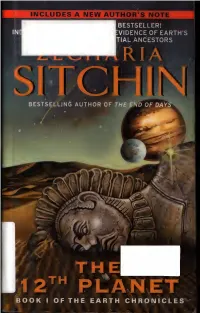

THE 12Th PLANET the STAIRWAY to HEAVEN the WARS of GODS and MEN the LOST REALMS WHEN TIME BEGAN the COSMIC CODE

INCLUDES A NEW AUTHOR'S P BESTSELLER! EVIDENCE OF EARTH’S TIAL ANCESTORS HARPER Now available in hardcover: U.S. $7.99 CAN. $8.99 THE LONG-AWAITED CONCLUSION TO ZECHARIA SITCHIN’s GROUNDBREAKING SERIES THE EARTH CHRONICLES ZECHARIA SITCHIN THE END DAYS Armageddon and Propfiffie.t of tlic Renirn . Available in paperback: THE EARTH CHRONICLES THE 12th PLANET THE STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN THE WARS OF GODS AND MEN THE LOST REALMS WHEN TIME BEGAN THE COSMIC CODE And the companion volumes: GENESIS REVISITED EAN DIVINE ENCOUNTERS . “ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT BOOKS ON EARTH’S ROOTS EVER WRITTEN.” East-West Magazine • How did the Nefilim— gold-seekers from a distant, alien planet— use cloning to create beings in their own image on Earth? •Why did these "gods" seek the destruc- tion of humankind through the Great Flood 13,000 years ago? •What happens when their planet returns to Earth's vicinity every thirty-six centuries? • Do Bible and Science conflict? •Are were alone? THE 12th PLANET "Heavyweight scholarship . For thousands of years priests, poets, and scientists have tried to explain how life began . Now a recognized scholar has come forth with a theory that is the most astonishing of all." United Press International SEP 2003 Avon Books by Zecharia Sitchin THE EARTH CHRONICLES Book I: The 12th Planet Book II: The Stairway to Heaven Book III: The Wars of Gods and Men Book IV: The Lost Realms Book V: When Time Began Book VI: The Cosmic Code Book VII: The End of Days Divine Encounters Genesis Revisited ATTENTION: ORGANIZATIONS AND CORPORATIONS Most Avon Books paperbacks are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchases for sales promotions, premiums, or fund-raising. -

The World of the Sumerian Mother Goddess

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Historia Religionum 35 The World of the Sumerian Mother Goddess An Interpretation of Her Myths Therese Rodin Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Ihresalen, Tun- bergsvägen 3L, Uppsala, Saturday, 6 September 2014 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor Britt- Mari Näsström (Gothenburg University, Department of Literature, History of Ideas, and Religion, History of Religions). Abstract Rodin, T. 2014. The World of the Sumerian Mother Goddess. An Interpretation of Her Myths. Historia religionum 35. 350 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-554- 8979-3. The present study is an interpretation of the two myths copied in the Old Babylonian period in which the Sumerian mother goddess is one of the main actors. The first myth is commonly called “Enki and NinপXUVDƣa”, and the second “Enki and Ninmaপ”. The theoretical point of departure is that myths have society as their referents, i.e. they are “talking about” society, and that this is done in an ideological way. This study aims at investigating on the one hand which contexts in the Mesopotamian society each section of the myths refers to, and on the other hand which ideological aspects that the myths express in terms of power relations. The myths are contextualized in relation to their historical and social setting. If the myth for example deals with working men, male work in the area during the relevant period is dis- cussed. The same method of contextualization is used regarding marriage, geographical points of reference and so on. -

'Rider of the Clouds' and 'Gatherer of the Clouds' MOSHE WEINFELD Hebrew University, Jerusalem

'Rider of the Clouds' and 'Gatherer of the Clouds' MOSHE WEINFELD Hebrew University, Jerusalem In a study on divine intervention in war, now in preparation, I am investigating various descriptions and epithets of the "divine warrior" in Homeric and Hesiodic litera ture. My observations lead me to the conclusion that these epithets were shaped under the impact of near easter'll mythological tradition. Some of the major motifs adduced are: 1) The shaking of the Olympos under the feet of Zeus,l as well as the epithets of Poseidon, el1osicbtbon and ennosigaios 'earth shaker',2 divine attributes, common in the Bible and in the literature of the ancient Near East. 2) Meteors, lightning and thunder as the divine weapon. 3 3) The cloud as the envelope of the deity and his carriers.4 4) The divine radiance encompassing gods and heroes.5 Most of these motifs are found-as shown in my study-in the divine imagery of T;; d'hypo possi megas pelemizet' Olympos (llias 8:443),possi d'hyp' . .. megas pelemizet' Olympos (Hesiod, Theog. 842), and see also lIias 13:18f: the high mountains and the woodland trembling beneath the feet of Poseidon. Compare the trembling of Mount Sinai in Exod. 19:18; PS, 18:8f. etc. and cf. the corresponding Mesopotamian descriptions cited by S. E. Loewenstamm in Oz le·David, Jubilee volume of D. Ben Gurion (Jerusalem, 1964), 514f.; and by J. Jeremias, Tbeopballie: Die Gescbicbte einer atl. Gattung (Neukirchen, 1965). In the Ugaritic literature only traces of this attribute can be found: bmt 'a[r11 tltn "the height of the earth trembled" (eTA 4, VII: 34-35). -

A Reconstruction of the Assyro-Babylonian God-Lists, AN

TEXTS FROM THE BABYLONIAN COLLECTION Volume 3 William W. Hallo, Editor TEXTS FROM THE BABYLONIAN COLLECTION Volume 3 ARECONSTRUCTION OF THE ASSYRO-BABYLONIAN GOD-LISTS, AN: dA NU-UM AND AN: ANU SA AMÉLI by Richard L. Litke LOC 98-061533 Copyright © 1998 by the Yale Babylonian Collection. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U. S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Printed in the United States of America Distributed by CDL Press, P.O.B. 34454 Bethesda, MD 20827, U.S.A. YALE BABYLONIAN COLLECTION New Haven The publication of thiS volume haS been made possible by a grant from Elizabeth DebevoiSe Healy in honor of her grandfather, Albert T. Clay. FOREWORD The publication of the present work has a long and complicated history. When FerriS J Stephens retired from the curatorship of the Babylonian Collection in 1962, and I arrived to take his place, one of the first problems confronting me was a large backlog of unfinished and half-finished manuscripts. These included dissertations written under the direction of Stephens or of Albrecht Goetze, and monographs and collections of copies prepared by former students and other collaborators. I therefore decided to bring the authorS in question back to New Haven to finish their manuscripts where possible, or to enlist other collaborators for the same purpose where it was not. To this end, applications were successfully made to the National Endowment for the Humanities for summer grants—five in all during the period 1968-77—which eventually resulted in, or contributed materially to, the publication of a dozen monographs (BIN 3, YNER 4-7, and YOS 11-14 and 17-18, as well as B. -

A Case Study of the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library Rare Books Collection

Rare books as historical objects: a case study of the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library rare books collection Item Type Thesis Authors Korotkova, Ulyana Aleksandrovna; Короткова, Ульяна Александровна Download date 10/10/2021 16:12:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/6625 RARE BOOKS AS HISTORICAL OBJECTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE ELMER E. RASMUSON LIBRARY RARE BOOKS COLLECTION By Ulyana Korotkova RECOMMENDED: Dr. Terrence M. Cole Dr. Katherine L. Arndt Dr. M ary^R^hrlander Advisory Committee Chair Dr. Mary^E/Ehrlander Director, Arctic and Northern Studies Program RARE BOOKS AS HISTORICAL OBJECTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE ELMER E. RASMUSON LIBRARY RARE BOOKS COLLECTION A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Ulyana Korotkova Fairbanks, AK May 2016 Abstract Once upon a time all the books in the Arctic were rare books, incomparable treasures to the men and women who carried them around the world. Few of these tangible remnants of the past have managed to survive the ravages of time, preserved in libraries and special collections. This thesis analyzes the over 22,000-item rare book collection of the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the largest collection of rare books in the State of Alaska and one of the largest polar regions collections in the world. Content, chronology, authorship, design, and relevance to northern and polar history were a few of the criteria used to evaluate the collection. Twenty items of particular value to the study of Alaskan history were selected and studied in depth. -

The Epic of Gilgamish

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM PUBLICATIONS OF THE BABYLONIAN SECTION VOL. x No. 3 THE EPIC OF GILGAMISH BY STEPHEN LANGDON PHILADELPHIA PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM 1917 INTRODUCTION In the year 1914the University Museum secured by pur- chase a large six column tablet nearly complete, carrying originally, according to the scribal note, 240 lines of text. The contents supply the South Babylonian version of the second book of the epic Sa nagba inzuru, “He who has seen all things,” commonly referred to as the Epic of Gilgamish, The tablet is said to have been found at Senkere, ancient Larsa near Wwka, modern Arabic name for and vulgar descendant of the ancient name Uruk, the Biblical Erech mentioned in Genesis x. IO. This fact makes the new text the more interesting since the legend of Gilgamish is said to have originated at Erech and the hero in fact figures as one of the prehistoric Sumerian rulers of that ancient city. The dynastic list preserved on a Nippur tablet1 mentions him as the fifth king of a legendary line of rulers at Erech, who succeeded the dynasty of Kish, a city in North Babylonia near the more famous but more recent city Babylon. The list at Erech contains the names of two well known Sumerian deities, Lugalbanda2 and Tammuz. The reign of the former is given at 1,200 years and that of Tammuz at 100 years. Gilgamish ruled 126 years. We have to do here with a confusion of myth and history in which the real facts are disengaged only by conjecture.