Nippur and Archaeology in Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bismya; Or the Lost City of Adab : a Story of Adventure, of Exploration

The Lost City of Adab 1 ' i %|,| / ";'M^"|('1j*)'| | Edgar James Banks l (Stanttll Wttfrmttg |fitag BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcm-ij W. Sage 1891 fjjRmf... Lifoi/jL 3777 Cornell University Library DS 70.S.B5B21 Bismya: or The lost city of Adab 3 1924 028 551 913 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028551913 The Author as an Arab. Bismya or The Lost City of Adab A Story of Adventure, of Exploration, and of Excavation among the Ruins of the Oldest of the Buried Cities of Babylonia By Edgar James Banks, Ph.D. Field Director of the Expedition of the Oriental Exploration Fund of the University of Chicago to Babylonia With 174 Illustrations G. P. Putnam's Sons New York and London Gbe IRnfcfeerbocfter press 1912 t.v. Copyright, 1912 BY EDGAR JAMES BANKS Ube TKniefeerbocftei: ipresg, mew ffiorft The University of Chicago office of the president Chicago, June 12, 1912. On the recommendation of the Director of the Baby- lonian Section of the Oriental Exploration Fund of the University of Chicago, permission has been granted to Dr. Edgar J. Banks, Field Director of the Fund at Bismya, to publish this account of his work in Mesopotamia. Dr. Banks was granted full authority in the field. He is entitled therefore to the credit for successes therein, as of course he will receive whatever criticism scholars may see fit to make. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from His Days Running Wild in the Forest

Gilgamesh's superiority. They hugged and became best friends. Name Always eager to build a name for himself, Gilgamesh wanted to have an adventure. He wanted to go to the Cedar Forest and slay its guardian demon, Humbaba. Enkidu did not like the idea. He knew The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from his days running wild in the forest. He tried to talk his best friend out of it. But Gilgamesh refused to listen. Reluctantly, By Vickie Chao Enkidu agreed to go with him. A long, long time ago, there After several days of journeying, Gilgamesh and Enkidu at last was a kingdom called Uruk. reached the edge of the Cedar Forest. Their intrusion made Humbaba Its ruler was Gilgamesh. very angry. But thankfully, with the help of the sun god, Shamash, the duo prevailed. They killed Humbaba and cut down the forest. They Gilgamesh, by all accounts, fashioned a raft out of the cedar trees. Together, they set sail along the was not an ordinary person. Euphrates River and made their way back to Uruk. The only shadow He was actually a cast over this victory was Humbaba's curse. Before he was beheaded, superhuman, two-thirds god he shouted, "Of you two, may Enkidu not live the longer, may Enkidu and one-third human. As king, not find any peace in this world!" Gilgamesh was very harsh. His people were scared of him and grew wary over time. They pleaded with the sky god, Anu, for his help. In When Gilgamesh and Enkidu arrived at Uruk, they received a hero's response, Anu asked the goddess Aruru to create a beast-like man welcome. -

Iraq Reconstruction Report a Weekly Construction & Sustainment Update 10.20.06

Iraq Reconstruction Report A Weekly Construction & Sustainment Update 10.20.06 Major Project Dispatches Fence Provides Additional Port Security The Umm Qasr security fence project at the port in Basrah Province was was completed on Oct. 5. The $4.1 million project installed approximately 8 kilometers of security fencing around the north and south port facilities. The project also included the building of an interior perimeter access road, observation posts, perimeter lighting, and back-up power capability. Major Baghdad Road Paving Project Completed Construction is complete on the road repair and paving project in Baiya, Baghdad Province. The $2.4 million project repaired and paved approximately 10 kilometers of Highway 8 between the Al Baiya/Qadisiya overpass and the Rashid Market traffic circle. Work included sealing cracks, patching potholes, road surface cleaning, and installing traffic signs. Construction Begins on an Al-Anbar Pump Station The Baghdad Central Train Station is a $6 million project Construction started on a Fallujah sewer system pump station in Al- completed by the Al Munshed Group, an Iraqi company. The Anbar Province. The $3.8 million project began this month, and has a station administrative offices, restaurant, kitchen areas, bank, June 2007 estimated completion date. The project will construct a facility post office, telegraph office and ticketing offices were all refurbished. (Gulf Region Division Photo) that will pump wastewater from five collection systems to a trunk collection system. The project will benefit approximately 140,000 Inside this Issue residents of Fallujah. Page 2 Gulf Region Division Change of Command Bringing Hope to Tarmiya Page 3 Sector Overview Page 4 School’s “In” Potable Water Page 5 New Police Training Station Capabilities Being UNDG Oversees Infrastructure Rehabilitation Page 6 Hole Repair: Important Work in Iraq Rebuilt Equipment Donated to Veterinary Center Page 8 DoD Reconstruction Partnership A Fallujah worker at the new Al Askari water treatment US Army Corps of Engineers - Gulf Region plant. -

Iraq Reconstruction Weekly Update اﻻﺳﺒﻮﻋﻰ ﻟﻤﺸﺎرﻳﻊ اﻋﻤﺎر اﻟﻌﺮاق اﻟﺘﺤﺪﻳﺚ

Iraq Reconstruction Weekly Update اﻻﺳﺒﻮﻋﻰ ﻟﻤﺸﺎرﻳﻊ اﻋﻤﺎر اﻟﻌﺮاق اﻟﺘﺤﺪﻳﺚ 12.07.05 ﺗﻄﻮر اﻟﺤﺪث واﻻﺧﺒﺎر اﻟﺠﻴﺪة ﺗﻘﺎرﻳﺮ ﻋﻦ Reporting progress and good news Progress Dispatches - Al Husseiniya Primary Healthcare Center Construction is 91% complete on the $653,000 primary healthcare center project in Rusafa, Baghdad Governorate. The project started in Oct. 2004 and will be completed Project Close Up… this month. The two-story, 1,155 BAGHDAD, Iraq – Iraqi police assigned to the newly square meter facility will provide modernized Najaf police station register their approval of medical and dental examination and treatment. The facility will the site’s renovation. Story Page ( Photo by Denise Calabria) be able to treat about 150 patients daily. This is one of 29 primary healthcare center projects programmed in the Baghdad Governorate. Notable Quotes - Al Kut Wasit Underground Line: Project Complete “You are in our way -- please leave so we can get back to work.” Construction has been completed on an electricity project that will Mr. Alla, an Iraqi sewer construction laborer, to reporters. provide service to over 200 Iraqi homes in Al Kut, Wasit (Oct. 2005) Governorate. The $1.5M Wasit Underground Line project installed Inside this Issue two new underground electrical feeders from the Al Kut South substation to the Al Ezah substation which will provide incoming Page 2 - Change of Charter - Electrical Substation Recognized for Excellence power to approximately 2,000 local residents. The Iraqi contractor Page 3 - Contracting Offices Help Boost Iraq’s Economy employed an average of 28 Iraqi workers daily on the site. - Control of Major Power Projects Turned Over - Al Shuada Sewer Work - Diwaniyah Rail Station: Project Complete Page 4 - Latest Project Numbers Page 5 - Sector Overview: Current Status/Impact Construction has been completed on Page 6 - Spotlight on Design-Build Contractors $181,000 railroad station project in Diwaniyah - Unit-Level Assistance in the News District, Al Qadisiyah Governorate. -

Who Is the Daughter of Babylon?

WHO IS THE DAUGHTER OF BABYLON? ● Babylon was initially a minor city-state, and controlled little surrounding territory; its first four Amorite rulers did not assume the title of king. The older and more powerful states of Assyria, Elam, Isin, and Larsa overshadowed Babylon until it became the capital of Hammurabi's short-lived empire about a century later. Hammurabi (r. 1792–1750 BC) is famous for codifying the laws of Babylonia into the Code of Hammurabi. He conquered all of the cities and city states of southern Mesopotamia, including Isin, Larsa, Ur, Uruk, Nippur, Lagash, Eridu, Kish, Adab, Eshnunna, Akshak, Akkad, Shuruppak, Bad-tibira, Sippar, and Girsu, coalescing them into one kingdom, ruled from Babylon. Hammurabi also invaded and conquered Elam to the east, and the kingdoms of Mari and Ebla to the northwest. After a protracted struggle with the powerful Assyrian king Ishme-Dagan of the Old Assyrian Empire, he forced his successor to pay tribute late in his reign, spreading Babylonian power to Assyria's Hattian and Hurrian colonies in Asia Minor. After the reign of Hammurabi, the whole of southern Mesopotamia came to be known as Babylonia, whereas the north had already coalesced centuries before into Assyria. From this time, Babylon supplanted Nippur and Eridu as the major religious centers of southern Mesopotamia. Hammurabi's empire destabilized after his death. Assyrians defeated and drove out the Babylonians and Amorites. The far south of Mesopotamia broke away, forming the native Sealand Dynasty, and the Elamites appropriated territory in eastern Mesopotamia. The Amorite dynasty remained in power in Babylon, which again became a small city-state. -

Your Android Tablet out of Date? Our Tablets Are 4000 Years Old! by Darlene F

Your Android tablet out of date? Our tablets are 4000 years old! By Darlene F. Lizarraga This is Part Two of a developing 4-part series titled, “Digging in Storage,” documenting the results of an independent study course, directed by Dr. Irene Bald Romano, fall 2013. Some among the younger generations might be surprised to know that tablets existed long before Apple and Microsoft created the high- definition, flat-screened versions so ubiquitous today. ASM object #68 is a 4000-year-old cuneiform tablet from ancient Sumer. This type of tablet, in its day, was equally high tech and equally ubiquitous. People living in ancient Mesopotamia—the area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers comprised of the empires of Assyria, Babylonia, Sumer, and often referred to as the “Cradle of Western Civilization”—developed one of the world’s earliest writing systems around 3100 BCE. ASM #68: Cuneiform Tablet Sumerian, Ur III period, 2056 BCE Tell Jokha, Iraq; ancient Umma, Mesopotamia Mesopotamian scribes recorded daily events, Baked clay trade, astronomy, literature, and even Height 3.58 inches (9.1 cm.) Width 2.04 inches (5.2 cm.) personal correspondence with wedge-shaped Thickness 0.91 inches (2.3 cm.) symbols known as cuneiform (Latin: cuneus = Purchased from Edgar J. Banks, 1914 wedge) on tablets of soft clay which, after being inscribed, were either sun-dried or kiln COME SEE THIS TABLET AND OTHER OLD baked. The writing utensil was probably reed, WORLD OBJECTS! ASM #68 and other highlights from ASM’s Near which could have either a pointed end or a Eastern, Egyptian, Greek, Etruscan, and Roman squared-off end, and would be used either to collections will be on display in the museum’s scratch or press in order to produce the script. -

The Extent and Geographic Distribution of Chronic Poverty in Iraq's Center

The extent and geographic distribution of chronic poverty in Iraq’s Center/South Region By : Tarek El-Guindi Hazem Al Mahdy John McHarris United Nations World Food Programme May 2003 Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Background:.........................................................................................................................................3 What was being evaluated? .............................................................................................................3 Who were the key informants?........................................................................................................3 How were the interviews conducted?..............................................................................................3 Main Findings......................................................................................................................................4 The extent of chronic poverty..........................................................................................................4 The regional and geographic distribution of chronic poverty .........................................................5 How might baseline chronic poverty data support current Assessment and planning activities?...8 Baseline chronic poverty data and targeting assistance during the post-war period .......................9 Strengths and weaknesses of the analysis, and possible next steps:..............................................11 -

The Epic of Gilgamesh Tablet V ... They Stood at the Forest's Edge

The Epic of Gilgamesh Tablet V ... They stood at the forest's edge, gazing at the top of the Cedar Tree, gazing at the entrance to the forest. Where Humbaba would walk there was a trail, the roads led straight on, the path was excellent. Then they saw the Cedar Mountain, the Dwelling of the Gods, the throne dais of Imini. Across the face of the mountain the Cedar brought forth luxurious foliage, its shade was good, extremely pleasant. The thornbushes were matted together, the woods(?) were a thicket ... among the Cedars,... the boxwood, the forest was surrounded by a ravine two leagues long, ... and again for two-thirds (of that distance), ...Suddenly the swords..., and after the sheaths ..., the axes were smeared... dagger and sword... alone ... Humbaba spoke to Gilgamesh saying :"He does not come (?) ... ... Enlil.. ." Enkidu spoke to Humbaba, saying: "Humbaba...'One alone.. 'Strangers ... 'A slippery path is not feared by two people who help each other. 'Twice three times... 'A three-ply rope cannot be cut. 'The mighty lion--two cubs can roll him over."' ... Humbaba spoke to Gilgamesh, saying: ..An idiot' and a moron should give advice to each other, but you, Gilgamesh, why have you come to me! Give advice, Enkidu, you 'son of a fish,' who does not even know his own father, to the large and small turtles which do not suck their mother's milk! When you were still young I saw you but did not go over to you; ... you,... in my belly. ...,you have brought Gilgamesh into my presence, ... you stand.., an enemy, a stranger. -

The Ubaid Period the Sumerian King List

Sumer by Joshua J. Mark published on 28 April 2011 Sumer was the southernmost region of ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq Map of Sumer (by P L Kessler, Copyright) and Kuwait) which is generally considered the cradle of civilization. The name comes from Akkadian, the language of the north of Mesopotamia, and means “land of the civilized kings”. The Sumerians called themselves “the black headed people” and their land, in cuneiform script, was simply “the land” or “the land of the black headed people”and, in the biblical Book of Genesis, Sumer is known as Shinar. According to the Sumerian King List, when the gods first gave human beings the gifts necessary for cultivating society, they did so by establishing the city of Eridu in the region of Sumer. While the Sumerian city of Uruk is held to be the oldest city in the world, the ancient Mesopotamians believed that it was Eridu and that it was here that order was established and civilization began. The Ubaid Period The region of Sumer was long thought to have been first inhabited around 4500 BCE. This date has been contested in recent years, however, and it now thought that human activity in the area began much earlier. The first selers were not Sumerians but a people of unknown origin whom archaeologists have termed the Ubaid people - from the excavated mound of al- Ubaid where the artifacts were uncovered which first aested to their existence - or the Proto-Euphrateans which designates them as earlier inhabitants of the region of the Euphrates River. Whoever these people were, they had already moved from a hunter- gatherer society to an agrarian one prior to 5000 BCE. -

Major Strategic Projects Available for Investment According to Sectors

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission MAJOR STRATEGIC (LARGE) AND (MEDIUM-SIZE)PROJECTS AVAILABLE FOR INVESTMENT ACCORDING TO SECTORS NUMBER OF INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES ACCORDING TO SECTORS No. Sector Number of oppurtinites Major strategic projects 1. Chemicals, Petrochemicals, Fertilizers and 18 Refinery sector 2 Transportation Sector including (airports/ 16 railways/highways/metro/ports) 3 Special Economic Zones 4 4 Housing Sector 3 Medium-size projects 5 Engineering and Construction Industries Sector 6 6 Commercial Sector 12 7 tourism and recreational Sector 2 8 Health and Education Sector 10 9 Agricultural Sector 86 Total number of opportunities 157 Major strategic projects 1. CHEMICALS, PETROCHEMICALS, FERTILIZERS AND REFINERY SECTOR: A. Rehabilitation of existing fertilizer plant in Baiji and the implementation of new production lines (for export). • Production of 500 ton of Urea fertilizer • Expected capital: 0.5 billion USD • Return on Investment rate: %17 • The plant is operated by LPG supplied by the North Co. in Kirkuk Province. 9 MW Generators are available to provide electricity for operation. • The ministry stopped operating the plant on 1/1/2014 due to difficult circumstances in Saladin Province. • The plant has1165 workers • About %60 of the plant is damaged. Reconstruction and development of fertilizer plant in Abu Al Khaseeb (for export). • Plant history • The plant consist of two production lines, the old production line produced Urea granules 200 t/d in addition to Sulfuric Acid and Ammonium Phosphate. This plant was completely destroyed during the war in the eighties. The second plant was established in 1973 and completed in 1976, designed to produce Urea fertilizer 420 thousand metric ton/y. -

Investment Map of Iraq 2016

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investment Map of Iraq 2016 Dear investor: Investment opportunities found in Iraq today vary in terms of type, size, scope, sector, and purpose. the door is wide open for all investors who wish to hold investment projects in Iraq,; projects that would meet the growing needs of the Iraqi population in different sectors. Iraq is a country that brims with potential, it is characterized by its strategic location, at the center of world trade routes giving it a significant feature along with being a rich country where I herby invite you to look at Iraq you can find great potentials and as one of the most important untapped natural resources which would places where untapped investment certainly contribute in creating the decent opportunities are available in living standards for people. Such features various fields and where each and characteristics creates favorable opportunities that will attract investors, sector has a crucial need for suppliers, transporters, developers, investment. Think about the great producers, manufactures, and financiers, potentials and the markets of the who will find a lot of means which are neighboring countries. Moreover, conducive to holding new projects, think about our real desire to developing markets and boosting receive and welcome you in Iraq , business relationships of mutual benefit. In this map, we provide a detailed we are more than ready to overview about Iraq, and an outline about cooperate with you In order to each governorate including certain overcome any obstacle we may information on each sector. In addition, face. -

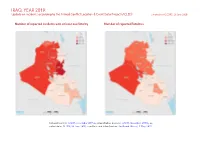

IRAQ, YEAR 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

IRAQ, YEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 IRAQ, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 1282 452 1253 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2019 2 Protests 845 12 72 Battles 719 541 1735 Methodology 3 Riots 242 72 390 Conflict incidents per province 4 Violence against civilians 191 136 240 Strategic developments 190 6 7 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 3469 1219 3697 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 IRAQ, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known.