Libertine Erudition: José Marchena's Fragmentum Petronii and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Treaty of Lunéville J. David Markham When Napoleon Became

The Treaty of Lunéville J. David Markham When Napoleon became First Consul in 1799, his first order of business was to defend France against the so-called Second Coalition. This coalition was made up of a number of smaller countries led by Austria, Russia and Britain. The Austrians had armies in Germany and in Piedmont, Italy. Napoleon sent General Jean Moreau to Germany while he, Napoleon, marched through Switzerland to Milan and then further south, toward Alessandria. As Napoleon, as First Consul, was not technically able to lead an army, the French were technically under the command of General Louis Alexandre Berthier. There, on 14 June 1800, the French defeated the Austrian army led by General Michael von Melas. This victory, coupled with Moreau’s success in Germany, lead to a general peace negotiation resulting in the Treaty of Lunéville (named after the town in France where the treaty was signed by Count Ludwig von Cobenzl for Austria and Joseph Bonaparte for Austria. The treaty secured France’s borders on the left bank of the Rhine River and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. France ceded territory and fortresses on the right bank, and various republics were guaranteed their independence. This translation is taken from the website of the Fondation Napoléon and can be found at the following URL: https://www.napoleon.org/en/history-of-the- two-empires/articles/treaty-of-luneville/. I am deeply grateful for the permission granted to use it by Dr. Peter Hicks of the Fondation. That French organization does an outstanding job of promoting Napoleonic history throughout the world. -

Nota De Prensa

MINISTERIO DE TRANSPORTES, MOVILIDAD Y AGENDA URBANA Línea de ancho convencional Bifurcación de Utrera-Fuente de Piedra La Variante de Aguadulce entra en servicio comercial el próximo lunes 31 de mayo La puesta en servicio se realiza tras la reciente firma del convenio que regula las condiciones que permiten la integración en la Red Ferroviaria de Interés General (RFIG) del tramo ferroviario comprendido entre los puntos kilométricos 90/100 y 99/400 del Eje Ferroviario Transversal. Se trata de un acuerdo entre el Ministerio, Junta de Andalucía, Agencia de Obra Pública de Andalucía y Adif, por el que el tramo, de unos 9,3 km, ha podido ser integrado en la RFIG tras la aprobación de la correspondiente Orden Ministerial. Renfe suprime los trasbordos por carretera en Osuna y Pedrera Nota de prensa para todos los trenes de Media Distancia Sevilla-Málaga Se pone en servicio una oferta diaria de ocho trenes, cuatro por sentido, con tiempo de viaje aproximado de 2h 45 minutos entre Sevilla y la capital de la Costa del Sol Adif ha invertido más de 7,3 M€ (IVA no incluido) en la obra de montaje de la vía y señalización del tramo, así como en la reparación puntual de daños en la infraestructura Madrid, 27 de mayo de 2021 (Mitma). Adif y Renfe anuncian la puesta en servicio comercial de la Variante de Aguadulce (Sevilla), perteneciente a la línea de ancho convencional Bifurcación Utrera-Fuente de Piedra, a partir del próximo lunes 31 de mayo. Esta puesta en servicio, se produce tras la firma del convenio que regula las condiciones que han permitido -

La Expulsión De La Compañía De Jesús De Utrera. El

A B O Religiosidad popular, devoción y patrimonio..., pp. 44-53 MORGADO, Alonso de (ed. 1887) Historia de Sevilla en la qual se contienen sus antigüedades, grandezas y cosas memorables en ella acontecidas, su fundación hasta nuestros días, 1587. ORTIZ DE ZÚÑIGA, Diego (ed. 1998) Anales eclesiásticos y se- culares de la muy Noble y muy Leal ciudad de Sevilla... desde el año 1246 hasta el de 1671... ilustrados y corregidos por Antonio María Espinosa y Cárcel, Madrid, 1795-1796 vol. II. RODRÍGUEZ BECERRA, Salvador (2012) «Advocaciones ma- rianas de gloria en Andalucía. Génesis y evolución de sus san- tuarios» en Advocaciones Marianas de Gloria. San Lorenzo del Escorial. — (2015) «Imágenes de María aparecidas y dolorosas en Anda- lucía: dos modelos de implantación devocional en» Virgo Dolo- rosa. Actas. Carmona. Fraternidad de la B. V. María Dolorosa. SÁNCHEZ HERRERO, José (1992) «Beguinos y Tercera Orden Regular de San Francisco en Castilla» en Historia. Instituciones. Documentos, n.º 19. Sevilla. Universidad de Sevilla. VVAA (1994) Boletín de la Iltre. Hdad. de Ntra. Sra. de Consola- ción, Patrona de Carrión de los Céspedes, II época, n.º 5. 1. E S F N, C S J C J U (S). F: A M P. LA EXPULSIÓN DE LA COMPAÑÍA DE misiones a pueblos cercanos a Sevilla, donde había captado JESÚS DE UTRERA. EL REPARTO DE algunos seguidores. En Utrera se había instituido, en la pa- rroquia mayor, una Congregación de seglares, a las que al pa- ALHAJAS Y BIENES INMUEBLES recer había asistido Villalpando. Por este motivo el arzobispo de Sevilla, don Pedro Vaca de Castro y Quiñones3, solicitó Por a la Compañía de Jesús de Sevilla que enviase a la locali- dad de Utrera a dos padres para que refundasen y dirigiesen A M P la congregación y prosiguiesen con prácticas espirituales y Centro de Intervención conferencias de moral semanales. -

Registro Vias Pecuarias Provincia Sevilla

COD_VP N O M B R E DE LA V. P. TRAMO PROVINCIA MUNICIPIO ESTADO LEGAL ANCHO LONGITUD PRIORIDAD USO PUBLICO 41001001 CAÑADA REAL DE SEVILLA A GRANADA 41001001_01 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 75 10 3 41001001 CAÑADA REAL DE SEVILLA A GRANADA 41001001_03 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 75 1629 3 41001001 CAÑADA REAL DE SEVILLA A GRANADA 41001001_02 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 75 2121 3 41001002 VEREDA DE OSUNA A ESTEPA 41001002_06 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 21 586 3 41001002 VEREDA DE OSUNA A ESTEPA 41001002_05 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 21 71 3 VEREDA DE SIERRA DE YEGÜAS O DE LA 41001003 PLATA 41001003_02 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 21 954 3 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_04 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 224 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_06 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 3244 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_07 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 57 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_08 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 17 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_05 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 734 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_01 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 1263 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_03 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 3021 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_02 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 428 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_09 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 2807 1 CAÑADA REAL DE CONSTANTINA Y DESLINDE 41002002 CAZALLA 41002002_02 SEVILLA -

Dreams of Al-Andalus; a Survey of the Illusive Pursuit of Religious Freedom in Spain

Dreams of al-Andalus; A Survey of the Illusive Pursuit of Religious Freedom in Spain By Robert Edward Johnson Baptist World Alliance Seville, Spain July 10, 2002 © 2002 by the American Baptist Quarterly a publication of the American Baptist Historical Society, P.O. Box 851, Valley forge, PA 19482-0851. Around 1481, a local chronicler from Seville narrated a most incredible story centering around one of the city’s most prominent citizens, Diego de Susán. He was among Seville’s wealthiest and most influential citizens, a councilor in city government, and, perhaps most important, he was father to Susanna—the fermosa fembra (“beautiful maiden”). He was also a converso, and was connected with a group of city merchants and leaders, most of whom were conversos as well. All were opponents to Isabella’s government. According to this narration, Susán was at the heart of a plot to overthrow the work of the newly created Inquisition. He summoned a meeting of Seville’s power brokers and other rich and powerful men from the towns of Utrera and Carmona. These said to one another, ‘What do you think of them acting thus against us? Are we not the most propertied members of this city, and well loved by the people? Let us collect men together…’ And thus between them they allotted the raising of arms, men, money and other necessities. ‘And if they come to take us, we, together with armed men and the people will rise up and slay them and so be revenged on our enemies.’[1] The fly in the ointment of their plans was the fermosa fembra herself. -

Pierre Riel, the Marquis De Beurnonville at the Spanish Court and Napoleon Bonaparte's Spanish Policy, 1802-05 Michael W

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Fear and Domination: Pierre Riel, the Marquis de Beurnonville at the Spanish Court and Napoleon Bonaparte's Spanish Policy, 1802-05 Michael W. Jones Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Fear and Domination: Pierre Riel, the Marquis de Beurnonville at the Spanish Court and Napoleon Bonaparte’s Spanish Policy, 1802-05 By Michael W. Jones A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester 2005 Copyright 2004 Michael W. Jones All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approved the dissertation of Michael W. Jones defended on 28 April 2004. ________________________________ Donald D. Horward Professor Directing Dissertation ________________________________ Outside Committee Member Patrick O’Sullivan ________________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member ________________________________ James Jones Committee Member ________________________________ Paul Halpern Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my father Leonard William Jones and my mother Vianne Ruffino Jones. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Earning a Ph.D. has been the most difficult task of my life. It is an endeavor, which involved numerous professors, students, colleagues, friends and family. When I started at Florida State University in August 1994, I had no comprehension of how difficult it would be for everyone involved. Because of the help and kindness of these dear friends and family, I have finally accomplished my dream. -

View the Enlightenment As a Catalyst for Beneficial Change in the Region

UNA REVOLUCION, NI MAS NI MENOS: THE ROLE OF THE ENLIGHTENMENT IN THE SUPREME JUNTAS IN QUITO, 1765-1822 Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Beau James Brammer, B.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Master’s Examination Committee: Kenneth Andrien, Adviser Stephanie Smith Alan Gallay Copyright by Beau James Brammer 2010 Abstract This thesis examines the role the European Enlightenment played in the political sphere during the late colonial era in the Audiencia of Quito. Until the eighteenth century, Creole elites controlled the local economic and governmental sectors. With the ascension of the Bourbon dynasty in 1700, however, these elites of Iberian descent began to lose their power as new European ideas, emerging from the Enlightenment, led to a process of consolidating and centralizing power into the hands of Peninsular Spanish officials. Known as the Bourbon Reforms, these measures led to Creole disillusionment, as they began losing power at the local level. Beginning in the 1770s and 1780s, however, Enlightenment ideas of “nationalism” and “rationality” arrived in the Andean capital, making their way to the disgruntled Creoles. As the situation deteriorated, elites began to incorporate these new concepts into their rhetoric, presenting a possible response to the Reforms. When Napoleon invaded Spain in 1808, the Creoles expelled the Spanish government in Quito, creating an autonomous movement, the Junta of 1809, using these Enlightenment principles as their justification. I argue, however, that while these ‘modern’ principles gave the Creoles an outlet for their grievances, it is their inability to find a common ground on how their government should interpret these new ideas which ultimately lead to the Junta’s failure. -

Proyecto De Dirección De D. Ginés Pastor Navarro

PROYECTO DE DIRECCIÓN I.E.S. RUIZ GIJÓN 2018 – 2022 Ginés Pastor Navarro Proyecto de Dirección (2018-2022) – IES Ruiz Gijón (Utrera) - Ginés Pastor Navarro INDICE 1. NORMATIVA ..................................................................................................................................................3 2. INTRODUCCIÓN ............................................................................................................................................3 2.1) Contexto social, cultural, económico y laboral .........................................................................................3 2.2) Justificación ...............................................................................................................................................5 2.3) Análisis de la situación personal y profesional del candidato ...................................................................6 3. ANÁLISIS Y DIAGNÓSTICO DEL CENTRO DOCENTE Y SU ENTORNO ............................................9 3.1) Análisis interno de la situación del Centro ................................................................................................9 3.1.1) Descripción física, dependencias y recursos ......................................................................................9 3.1.2) El horario del Centro ........................................................................................................................11 3.1.3) El profesorado del Centro ................................................................................................................11 -

Muslims in Spain, 1492–1814 Mediterranean Reconfigurations Intercultural Trade, Commercial Litigation, and Legal Pluralism

Muslims in Spain, 1492– 1814 Mediterranean Reconfigurations Intercultural Trade, Commercial Litigation, and Legal Pluralism Series Editors Wolfgang Kaiser (Université Paris I, Panthéon- Sorbonne) Guillaume Calafat (Université Paris I, Panthéon- Sorbonne) volume 3 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ cmed Muslims in Spain, 1492– 1814 Living and Negotiating in the Land of the Infidel By Eloy Martín Corrales Translated by Consuelo López- Morillas LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: “El embajador de Marruecos” (Catalog Number: G002789) Museo del Prado. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Martín Corrales, E. (Eloy), author. | Lopez-Morillas, Consuelo, translator. Title: Muslims in Spain, 1492-1814 : living and negotiating in the land of the infidel / by Eloy Martín-Corrales ; translated by Consuelo López-Morillas. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2021] | Series: Mediterranean reconfigurations ; volume 3 | Original title unknown. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020046144 (print) | LCCN 2020046145 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004381476 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004443761 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Muslims—Spain—History. | Spain—Ethnic relations—History. -

What We Learn from the Stephen Girard Collection – by Elizabeth Laurent – Former Director of Historic Resources, Girard College

Click Here to Return to Home Page and Main Menu Real and Rare: What We Learn from the Stephen Girard Collection – By Elizabeth Laurent – Former Director of Historic Resources, Girard College A joy of my job is The Archives holds Stephen Girard’s Papers, a collection sharing the Stephen available on microfilm to researchers at the Philadelphia’s Girard Collection with American Philosophical Society. The Girard Papers current Girard College include over 800 boxes of “loose” papers of incoming students. Sometimes, correspondence; receipts; lists; construction, garden and the students, seeing ship records; and architectural I’m so much older than drawings. We have three they, figure I must have thousand of Girard’s bound been alive in the 1800’s volumes, including year-by- and ask, “Mrs. Laurent, year receipt books, copies of his did you know Stephen outgoing correspondence, ship Portrait of Stephen Girard Girard?” By Bass Otis, 1832 log books, maps, bank records This is a funny but reasonable question. They rightly and his personal library. wonder how I know anything about Stephen Girard. At our museum in The glory of the Stephen Founder’s Hall on the Girard Collection is how Girard College campus, its authentic and varied we preserve thousands objects give us a sense of of objects from Girard’s the man. The artifacts Philadelphia townhouse: reflect their owner, being a Founder’s Hall on the Girard College his furniture, silver, Girard’s bound volumes personal collection of items sculpture, paintings, prints both plain and fancy. and porcelain. The collection also includes everyday items, It is rare for a man’s artifacts and archives to remain together like his clothing, darned socks and toupee; and household long after his death. -

La Algaba, Sevilla)

Fallecidos en el campo de concentrarción de Las Arenas (La Algaba, Sevilla) María Victoria Fernández Luceño José María García Márquez Apellidos, nombre Vecindario Edad Fallecimiento Álamo González, Juan Pedro Las Palmas de G. Canaria 54 02-01-1942 Albalaz Cordón, José Martos (Jaén) 20 10-02-1942 Alfalla Sousa, Luis Sevilla 46 06-03-1942 Álvarez González, Gerardo O Rosal (Pontevedra) 48 08-01-1942 Álvarez Martos, Diego Jaén 52 11-02-1942 Apolo Azogil, Guillermo Valverde del Camino (Huelva) 39 02-03-1942 Armario Fernández, Juan Sevilla 33 10-05-1942 Aroba Amador, José El Puerto de Santa María (Cádiz) 58 25-03-1942 Bacares Sol, Polonio Guadalimar (Jaén) 31 22-12-1941 Bando Rincón, José Sevilla 23 23-04-1942 Benítez Castro, Santiago Alhama de Granada 35 02-05-1942 Blanco Herce, Alfonso Bailén (Jaén) 55 10-12-1941 Bochet Merino, Luis Sevilla 48 05-05-1942 Cabrera Segovia, Manuel Sevilla 28 21-02-1942 Canales Beltrán, Juan Montoro (Córdoba) 50 16-04-1942 Cano Toledano, Manuel Sevilla 40 28-07-1942 Carballo López, Antonio Sevilla 19 27-02-1942 Carrera Martínez, Luis Sevilla 33 21-02-1942 Castellano Campo, José María Linares (Jaén) 27 05-03-1942 Del Castillo Gómez, Juan Rociana del Condado (Huelva) 46 27-02-1942 Castillo Paredes, Ventura Autillo de Campos (Palencia) 68 28-04-1942 Collado Pérez, Pedro Sorbas (Almería) 35 25-03-1942 Conde Pineda, Miguel Sevilla 47 18-09-1941 Coraza Clemente, Enrique Sevilla 53 06-04-1942 Corchero Fernández, José Utrera (Sevilla) 54 19-01-1942 Cruz Domínguez, José Puebla de Guzmán (Huelva) 44 03-05-1942 Delgado Lima, -

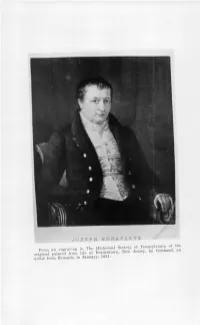

From an Engraving in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania of The

From an engraving in The Historical Society of Pennsylvania of the original painted from life at Bordentown, New Jersey, by Goubaud, an artist from Brussels, in January, 1831. 208 Joseph Bonaparte JOSEPH BONAPARTE as recorded in the Private Journal of Nicholas Biddle With an Introduction and Notes By EDWARD BIDDLE Joseph Bonaparte, eldest brother of the Emperor Napoleon (Bonaparte), arrived in this country in Au- gust, 1815—landing in New York on the twenty-eighth of the month—the passage from Bordeaux having con- sumed thirty-four days. It was not without risk of capture that Joseph suc- ceeded in reaching the soil of this country. Two En- glish war-vessels had overhauled the ship after leaving Bordeaux, but appeared satisfied with the passports that had been secured before sailing. Joseph's was in the name of Surviglieri, anticipating by analogy the one of Survilliers later adopted in this country. Joseph and his small suite lingered a few days in New York before setting out for Washington, D. C, passing through Philadelphia and Baltimore en route; the object of this journey being a proposed call on President Madison. For political reasons and for fear of embarrassing the Administration, Madison declined to receive Joseph—so that being apprized of this deci- sion after leaving Baltimore, he did not continue his journey to the Capitol. On the journey back he passed through Lancaster, Pennsylvania, being entertained there by a Mr. Slaymaker. He reached Philadelphia on the eighteenth of September, 1815. Napoleon had advised him to take up his residence in this country somewhere between Philadelphia and New York, so that news from the Old World could readily reach him.