Andalusia, Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Algeciras En La Encrucijada De La Batalla Del Estrecho (Siglos Xiii Y Xiv)

ALGECIRAS EN LA ENCRUCIJADA DE LA BATALLA DEL ESTRECHO (SIGLOS XIII Y XIV) Por MANUEL GONZÁLEZ JIMÉNEZ En el presente año se conmemoran dos importantes cente- narios: el de la batalla de las Navas de Tolosa (1212) y el inicio del reinado de Alfonso XI, bisnieto de Alfonso X el Sabio e hijo de Fernando IV “el Emplazado”. Alfonso XI accedió al trono en 1312, apenas con dos años de edad. Tras una larga y agitada minoría, en 1325 se anticiparía su mayoría de edad. Tenía apenas catorce años. A pesar de ello, protagonizó uno de los reinados más brillantes de la Baja Edad Media. Supo pacificar el reino y dotarlo de leyes nuevas y, por si fuera poco, proseguir con éxito la reconquista, reiniciando así el enfrentamiento por el control de la orilla europea del Estrecho de Gibraltar, tema que los histo- riadores llamamos desde hace tiempo la “batalla del Estrecho”. Vamos a tratar brevemente de este asunto que culminaría con la conquista de Algeciras que fue, junto con la de Tarifa, conquista- da en 1292, la llave del acceso a la Península. LA CRUZADA DE ALFONSO X CONTRA ÁFRICA Al acceder al trono Alfonso X el 1º de junio de 1252, todo lo que quedaba de al-Andalus estaba sometido por tributo al rey de Castilla. Era tiempo de pensar en el encargo que su padre Fernando III le hiciera en su lecho de muerte: proseguir la guerra contra los musulmanes en África. Se trataba de un proyecto, aca- riciado por el Santo Rey, como nos informa la Primera Crónica 453 454 MANUEL GONZÁLEZ JIMÉNEZ General. -

Suardiaz Groupgroup P

SUARDIAZSUARDIAZ GROUPGROUP SUARDÍAZ GROUP MAY 2010 SUARDIAZ GROUP - ACTIVITIES GRUPO LOGISTICO SUARDIAZ FLOTA SUARDIAZ PECOVA, Rail Transport LOGISTICA SUARDIAZ FLOTA SUARDIAZ, ROAD TRANSPORT RORO SERVICE SSMB BUNKER SUPPLIES MARITIME AGENCIES GRIMALDI SUARDIAZ INLAND TERMINALS SSS SERVICE STEVEDORING PORTS TERMINALS and and OTHERS STEVEDORING SUARDIAZ GROUP • Suardiaz has been operating for over a century. The head office is located in Madrid, and it renders services throughout Spain and Europe through its network of Delegations and Agencies. • We have own offices all around Spain, 14 offices, main ports, Bilbao, Santander, Gijon, Vigo, Barcelona, Tarragona, Valencia, Sevilla, Cadiz, Algeciras, Tenerife, Las Palmas GC, Madrid, Toledo. • The Suardiaz Group is one of Europe’s most important transport companies in terms of tradition and experience in the maritime logistics and rolling cargo sector. SUARDIAZ GROUP • Our organisational structure allows it to offer clients, integrated logistics and cargo transport services that meet current market demand while constantly making sure to strictly comply with quality and safety standards. Multimode transport (sea, land, air, and rail) Ship Owner Ship Agent Forwarding Chartering Port Operations Storage, deposits, and handling Customs agency Bunkering • In the past few years, the Company has been developing a diversification plan. As a result, new activities have been taken up such as bunkering and transporting crude oil. • Member of the main associations in the transport and logistic market as WWSA, FETEIA, IATA, BIMCO, etc… • Certified by LR ISO 9001. SUARDIAZ GROUP FLOTA SUARDIAZ SUARDIAZ GROUP • Flota Suardiaz is one of Europe’s most experienced and traditional shipping companies when it comes to logistics, transporting vehicles and rolling cargo by sea. -

Gines Recibe 1.229.178 Euros Para La Optimización Del Alumbrado Público

EL PERIÓDICODE TU INFORMACIÓN MÁS CERCANA ENERO DE 2015 - AÑO 2 - NÚMEROGINES 11- GRATUITO Entrevista Reportaje: Repaso al a la artista Gines da el paso año deportivo Laura de los con María de los clubes Ángeles locales PÁGINA 6 PÁGINAS 12-13 PÁGINAS 20-21 El teléfono de Gines recibe 1.229.178 euros para la la Policía Local será único y optimización del alumbrado público gratuito a Junta de Andalucía en el mar- partir del 1 de febrero, el Lco del Programa de Subvencio- A nuevo teléfono gratuito de la nes para el Desarrollo Energético Policía Local pasará a ser el único Sostenible de “Andalucía A+”, ha número de contacto de este ser- concedido al municipio un incen- vicio municipal, desapareciendo tivo de 1.229.178 euros para la op- todos los teléfonos anteriores. timización energética integral de su Así, el único en funcionamiento alumbrado público. será el 900.878.052, que se puso Con ello se sustituirán las actuales en marcha el pasado mes de junio luminarias, de tecnología conven- y que permite a los vecinos y cional, por otras totalmente nuevas vecinas contactar con la Policía de LED, lo que se traducirá en un Local sin coste alguno en su ahorro por parte del Ayuntamiento factura telefónica. de su factura energética (130.270 euros anuales), evitando también la emisión de 255,3 toneladas anua- 900.878.052 les de CO2. Trasladado al día a día significaría retirar de la circulación más de 100 vehículos en la localidad La actuación prevista consistirá también en la incorporación de sis- temas de telegestión en los cuadros de mando, que permiten un mejor control del gasto y un mejor man- tenimiento y funcionamiento de las instalaciones. -

17 Juli 1984 Houdende Algemene Voorschriften Inzake De Toekenning Van De Produktiesteun Voor Olijfolie En De in Bijlage II Van Verordening (EEG) Nr

Nr. L 122/64 Publikatieblad van de Europese Gemeenschappen 12. 5. 88 VERORDENING (EEG) Nr. 1309/88 VAN DE COMMISSIE van 11 mei 1988 tot wijziging van Verordening (EEG) nr. 2502/87 houdende vaststelling van de opbrengst aan olijven en aan olie voor het verkoopseizoen 1986/1987 DE COMMISSIE VAN DE EUROPESE geerd, gezien het feit dat de begunstigden de produktie GEMEENSCHAPPEN, steun nog , niet hebben kunnen ontvangen ; Gelet op het Verdrag tot oprichting van de Europese Overwegende dat de in deze verordening vervatte maatre Economische Gemeenschap, gelen in overeenstemming zijn met het advies van het Gelet op Verordening nr. 136/66/EEG van de Raad van Comité van beheer voor oliën en vetten. 22 september 1966 houdende de totstandbrenging van een gemeenschappelijke ordening der markten in de sector oliën en vetten ('), laatstelijk gewijzigd bij Verorde HEEFT DE VOLGENDE VERORDENING ning (EEG) nr. 1098/88 (2), en met name op artikel 5, lid VASTGESTELD : 5, Gelet op Verordening (EEG) nr. 2261 /84 van de Raad van Artikel 1 17 juli 1984 houdende algemene voorschriften inzake de toekenning van de produktiesteun voor olijfolie en de _ In bijlage II van Verordening (EEG) nr. 2502/87 worden steun aan de producentenorganisaties (3), laatstelijk gewij de gegevens betreffende de autonome gemeenschappen zigd bij Verordening (EEG) nr. 892/88 (4), en met name Andalusië en Valencia vervangen door de gegevens die op artikel 19, zijn opgenomen in de bijlage van deze verordening. Overwegende dat bij Verordening (EEG) nr. 2502/87 van Artikel 2 de Commissie (*), gewijzigd bij Verordening (EEG) nr. 370/88 (*), de opbrengst aan olijven en aan olie is vastge Deze verordening treedt in werking op de dag van haar steld voor de homogene produktiegebieden ; dat in bijlage bekendmaking in het Publikatieblad van de Europese II van die verordening vergissingen zijn geconstateerd Gemeenschappen. -

Sierra Morena De Jaén

25 RÓN DE CALDE SIERRAS VILLARRODRIGO !.Torreón de Génave Castillo de la Laguna%2 Torre de la Tercia RIÓN !. GENAVE ALDEAQUEMADA Castillo de%2 Matamoros SIERRAS DE CALDERONES DE CAMB PASO DE SIERRAS DE QUINTANA DESPEÑAPERROS SIERRAS PUENTE DE GÉNAVE VENTA DE LOS SANTOS CENTENILLO (EL) SANTA ELENA ALDEAHERMOSA ARROYO DEL OJANCO NAVAS DE TOLOSA CHICLANA DE SEGURA CAROLINA (LA) Río Guadalén !.Torres de la Aduana Río Pinto SANTISTEBAN DEL PUERTO Torreón con Espadaña %2 CASTELLAR Río Jándula !. !. Castillo de San EstebanTorre Cerro de San!. Marcos SORIHUELA DEL GUADALIMAR CARBONEROS Torre de la Ermita de Consolación Castillo del Cerro de la Virgen #0 VIRGEN DE LA CABEZA %2 VILCHES #0 #0 GUARROMAN#0 NAVAS DE SAN JUAN VIRGEN DE LA CABEZA BAÑOS DE LA ENCINA#0 LUGAR NUEVO (EL) #0 CRUZ (LA) Río Guadalimar ESTACION DE VADOLLANO %2Zona Arqueológica de Giribaile MIRAELRIO Río Rumblar ERMITAS CASTILLOS N ESCALA 1:600.000 TORRES - REFERENTES VISUALES RED FERROVIARIA RÍOS El extremo oriental de Sierra Morena se integra dentro de las áreas paisajísticas de Serranías de montaña media, Serranías de baja montaña y Campiñas de EJES PRINCIPALES piedemonte. Durante mucho tiempo ha sido la puerta de entrada a Andalucía desde la meseta y, por lo tanto, uno de los primeros paisajes que han percibido los viajeros. EJES SECUNDARIOS Aunque comparte buena parte de la caracterización paisajística de otras zonas de este sistema montañosos (especialmente el protagonismo de la dehesa), aquí cabe DEMARCACIÓN destacar que las alturas medias son mayores y que el carácter es más agreste y despoblado, sobre todo hacia oriente. La Loma de Chiclana, en cambio, escalón de Sierra Morena hacia el sureste, es un espacio en el que el olivo retoma el REPRESENTACIONES RUPESTRES protagonismo del paisaje. -

The Heritage of AL-ANDALUS and the Formation of Spanish History and Identity

International Journal of History and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) Volume 3, Issue 1, 2017, PP 63-76 ISSN 2454-7646 (Print) & ISSN 2454-7654 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-7654.0301008 www.arcjournals.org The Heritage of AL-ANDALUS and the Formation of Spanish History and Identity Imam Ghazali Said Indonesia Abstract: This research deals with the Islamic cultural heritage in al-Andalus and its significance for Spanish history and identity. It attempts to answer the question relating to the significance of Islamic legacies for the construction of Spanish history and identity. This research is a historical analysis of historical sources or data regarding the problem related to the place and contribution of al-Andalus’ or Islamic cultural legacies in its various dimensions. Source-materials of this research are particularly written primary and secondary sources. The interpretation of data employs the perspective of continuity and change, and continuity and discontinuity, in addition to Foucault’s power/knowledge relation. This research reveals thatal-Andalus was not merely a geographical entity, but essentially a complex of literary, philosophical and architectural construction. The lagacies of al-Andalus are seen as having a great significance for the reconstruction of Spanish history and the formation of Spanish identity, despite intense debates taking place among different scholar/historians. From Foucauldian perspective, the break between those who advocate and those who challenge the idea of convivencia in social, religious, cultural and literary spheres is to a large extent determined by power/knowledge relation. The Castrian and Albornozan different interpretations of the Spanish history and identity reflect their relations to power and their attitude to contemporary political situation that determine the production of historical knowledge. -

Spanish Autonomous Communities and EU Policies by Agustín Ruiz Robledo

ISSN: 2036-5438 Spanish Autonomous Communities and EU policies by Agustín Ruiz Robledo Perspectives on Federalism, Vol. 5, issue 2, 2013 Except where otherwise noted content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons 2.5 Italy License E - 29 Abstract The European Union affects not only the competences of the Governments and Parliaments, but also of all public authorities, in particular the powers of sub-state entities of compound states, who saw how decisions that their governments could not adopt domestically nevertheless ended up being adopted in Europe. This affected the competences of these sub-state entities, which had no representation in Europe – or, to put it shortly, no voice and no vote. Or rather, in the expressive German phrase: the European Community had long practised Landesblindheit. This paper considers the evolving role of Spanish Autonomous Communities in shaping EU norms and policies. The presentation follows the classical model of distinguishing between the ascendant phase of European law and its descendant phase. Finally, it shall discuss the relationships that the Autonomous Communities have developed regarding the Union or any of its components and which can be grouped under the expressive name of “paradiplomacy” or inter-territorial cooperation. Key-words Spain, Autonomous Communities, regional parliaments, European affairs Except where otherwise noted content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons 2.5 Italy License E - 30 1. Historical overview The political and legal developments of the institutions created by the Treaty of Rome in 1957 quickly demonstrated that the European Economic Community was not an international organization in the classic sense, a structure of states which agree in principle on topics far removed from the citizens’ everyday life, but instead it was something rather different, an organization with the capacity to adopt rules directly binding for all persons and public authorities of the Member States. -

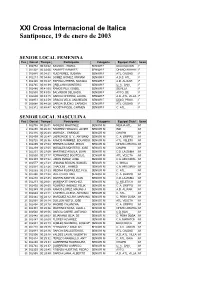

XXI Cross Internacional De Italica Santiponce, 19 De Enero De 2003

XXI Cross Internacional de Italica Santiponce, 19 de enero de 2003 SENIOR LOCAL FEMENINA Pos Dorsal Tiempo Participante Categoria Equipo/ Club/ Sexo 1 002752 00:34:02 BAUSAN ., ISABEL SENIOR F DELEGACIONColegio F 2 002302 00:34:06.37 RAMIREZ RAMIREZ, SENIOR F OHMIOPROV. DE ARAHAL ATL. F 3 002685 00:34:31.60 RUIZDOLORES PEREZ, SUSANA SENIOR F ATL. CIUDAD F 4 002213 00:34:44.16 GOMEZ GOMEZ, MIRIAM SENIOR F A.D.S.DE MOTRIL ATL. F 5 002346 00:35:27.28 ESPINO UTRERA, NATALIA SENIOR F A.D. ALIXAR F 6 002745 00:38:39.07 ORELLANA MONTERO, SENIOR F U. A . SAN F 7 002486 00:41:00.64 RAMOSELISA PILA, ISABEL SENIOR F SEVILLAFERNANDO F 8 002530 00:43:05.80 SALVADOR DELGADO, SENIOR F AYTO.ABIERTA DE F 9 002600 00:43:15.60 GARCIAROCIO CHORRO, LAURA SENIOR F A.D.CAZALLA ATL. VILLA F 10 000951 00:43:59.14 GRACIA VELA, ANA BELEN SENIOR F DELG.DE CABEZON PROV. F 11 002684 00:44:28.42 GARCIA BUENO, CARMEN SENIOR F ATL.DE JAN CIUDAD F 12 002312 00:45:47.30 ACOSTA POZO, CARMEN SENIOR F C.DE ATL. MOTRIL F .96 CHIPIONA SENIOR LOCAL MASCULINA Pos Dorsal Tiempo Participante Categoria Equipo/ Club/ Sexo 1 002735 00:26:01 ARNEDO MARTINEZ, SENIOR M NERJAColegio ATL. M 2 002268 00:26:38.19 RAMIREZGUILLERMO HIDALGO, JAVIER SENIOR M IND M 3 002316 00:26:40.08 MORAZA ., ENRIQUE SENIOR M CHAPIN M 4 002499 00:26:47.51 LADRON DE G. -

Ated in Specific Areas of Spain and Measures to Control The

No L 352/ 112 Official Journal of the European Communities 31 . 12. 94 COMMISSION DECISION of 21 December 1994 derogating from prohibitions relating to African swine fever for certain areas in Spain and repealing Council Decision 89/21/EEC (94/887/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, contamination or recontamination of pig holdings situ ated in specific areas of Spain and measures to control the movement of pigs and pigmeat from special areas ; like Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European wise it is necessary to recognize the measures put in place Community, by the Spanish authorities ; Having regard to Council Directive 64/432/EEC of 26 June 1964 on animal health problems affecting intra Community trade in bovine animals and swine (') as last Whereas it is the objective within the eradication amended by Directive 94/42/EC (2) ; and in particular programme adopted by Commission Decision 94/879/EC Article 9a thereof, of 21 December 1994 approving the programme for the eradication and surveillance of African swine fever presented by Spain and fixing the level of the Commu Having regard to Council Directive 72/461 /EEC of 12 nity financial contribution (9) to eliminate African swine December 1972 on animal health problems affecting fever from the remaining infected areas of Spain ; intra-Community trade in fresh meat (3) as last amended by Directive 92/ 1 18/EEC (4) and in particular Article 8a thereof, Whereas a semi-extensive pig husbandry system is used in certain parts of Spain and named 'montanera' ; whereas -

C31a Die 15I V I L L $

~°rOV17 C31a die 15i V I L L $ Comprende esta provincia los siguientes Municipios por partidos judiciales . Partido de Carmona . Partido de Morán de la, Frontera. Campana (La) . AL-tirada del Alear . Algamitas . Morón de la Frontera . Coripe . r mona . Viso del Alcor (El) Pruna. Coronil (El) . Montellano . Puebla de Cazalla (La) . Partido de Cazalla de a Sierra . Partido de Osuna . Alarde . Na•,'a .s de la Concepció n Altuadén de la Plata . (Las) . Cazalla de le Sierra, 1'('dro .so (El) . Cunslantina, lleal de la . Jara (El) . Corrales (Los) . Rubio (El) . (Iemlalee ia , San Nieol ;ís del Puerto Lantejuela (La.) . Naucejo (BO . Martín (le la Jara . Osuna . Villanueve de San Juau . Partido de Écija. Partido de Sanlúcar la Mayor. Coija . ? .uieie(ia . (L,e fuentes de Andalucía . Alhaida de Aljarafe . Madroño (PIl} . Aznalcázar . Olivares . Aznalcóllar. Pilas. Partido de Estepa. IJenacazón . Ronquillo (El) . ('arrión de los Céspedes. Saltaras. Castilleja del Campo . Sanlúcar lal Mayor. Castillo de las Guarda s ITmbrete. Aguadulee . I Ferrera .. (El) . Villamanrique de la Con - Itadolatosa . Lora de Estepa, - Iüspartinas . lesa. Casariche, Marinaleda . ifuévar . Villanueva del Ariseal . Estepa . Pedrera, (Mena .. Roda ale Andalucía (Lo ) Partidos (cinco) de Sevilla . Partido de Lora del Río . Alardea del Río . Puebla de les. Infantes Alead -1 del Río . (La) . Gel ves . (°antillana . Algaba (La) . Tetina . Gerena Atmensilla . Gines ora del Río . Villanueva del 'Rfo . llollullos de la Mitación 1' ileflor . t'illaverde del Río . Guillada. llormujos . M-airena . del Aljarafe _ Tiranas . Palomares del Rfo . liurguillo .. Puebla del Río (La} . Camas. Rinconada (La) . Partido de Marchena . Castilblaneo de los Arro- San Juan de Azna1f- .,a s yos . -

Campiña De Sevilla

08 Río Genil Río Guadalquivir Castillo de La Monclova ECIJA %2 LA LUISIANA VÍA AUGUSTA Río Corbones CARMONA %2 ITÁLICA FUENTES DE ANDALUCIA Castillo CORNISA DE TARAZONA LOS ALCORES %2Castillo de Alhonoz VISO DEL ALCOR (EL) MAIRENA DEL ALCOR HERRERA SEVILLA Castillo de la Mota-Palacio Ducal%2MARCHENA Río Guadaira ESTEPA Torre de la Membrilla !.%2 Torre Abad!. III !. Torre del Palacio del Recinto Amurallado ARAHAL OSUNA PEDRERA PUEBLA DE CAZALLA (LA) UTRERA Torre del Bao Castillo !. Castillo de Luna %2 Torre del Cortijo Palomo %2 !. VÍA AUGUSTA MORON DE LA FRONTERA %2Castillo Torre de la VentosillaTorre de la Ventilla #0 !. %2Castillo !.Torre de Troya !.Torre del Águila %2Castillo de las Aguzaderas #0 #0 ALINEACIÓN SISTEMA DE TORRES !.Torre del Bollo Torre Alocaz Castillo de CoteTorre Cote CABEZAS DE SAN JUAN (LAS) !. !. !.Torre Lopera Castillo%2%2 LEBRIJA ERMITAS CASTILLOS, FORTIFICACIONES N TORRES - REFERENTES VISUALES ESCALA 1:500.000 RED FERROVIARIA Territorio de campiña baja con paisajes intensamente antropizados con cultivos agrícolas intensivos de herbáceos en grandes explotaciones y parcelas, hoy RÍOS mecanizados. Se enmarca dentro de las áreas paisajísticas de Campiñas alomadas, acolinadas y sobre cerros y Valles, vegas y marismas interiores. Los paisajes urbanos EJES PRINCIPALES son ordenados y compactos en grandes núcleos (agrociudades), si bien los procesos urbanísticos de los últimos años tienden a minusvalorar la rica arquitectura popular y a EJES SECUNDARIOS degradar y alterar los bordes urbanos. La importancia histórica de la campiña sevillana se liga a la riqueza de los profundos suelos que componen estas comarcas, sin duda entre los más ricos de secano de la península. -

Forecasting of Short-Term Flow Freight Congestion: a Study Case of Algeciras Bay Port (Spain) Predicción a Corto Plazo De La Co

Forecasting of short-term flow freight congestion: A study case of Algeciras Bay Port (Spain) Juan Jesús Ruiz-Aguilar a, Ignacio Turias b, José Antonio Moscoso-López c, María Jesús Jiménez-Come d & Mar Cerbán e a Intelligent Modelling of Systems Research Group, University of Cádiz, Algeciras, Spain. [email protected] b Intelligent Modelling of Systems Research Group, University of Cádiz, Algeciras, Spain. [email protected] c Intelligent Modelling of Systems Research Group, University of Cádiz, Algeciras, Spain. [email protected] d Intelligent Modelling of Systems Research Group, University of Cádiz, Algeciras, Spain. marí[email protected] e Research Group Transport and Innovation Economic, University of Cádiz, Algeciras, Spain. [email protected] Received: November 04rd, 2014. Received in revised form: June 12th, 2015. Accepted: December 10th, 2015. Abstract The prediction of freight congestion (cargo peaks) is an important tool for decision making and it is this paper’s main object of study. Forecasting freight flows can be a useful tool for the whole logistics chain. In this work, a complete methodology is presented in order to obtain the best model to predict freight congestion situations at ports. The prediction is modeled as a classification problem and different approaches are tested (k-Nearest Neighbors, Bayes classifier and Artificial Neural Networks). A panel of different experts (post–hoc methods of Friedman test) has been developed in order to select the best model. The proposed methodology is applied in the Strait of Gibraltar’s logistics hub with a study case being undertaken in Port of Algeciras Bay. The results obtained reveal the efficiency of the presented models that can be applied to improve daily operations planning.