Kiwicītowek Insiniwuk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Each Other

LINDA M. GOULET AND KEITH N. GOULET TEACHING EACH OTHER Nehinuw Concepts and Indigenous Pedagogies Sample Material © 2014 UBC Press © UBC Press 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in Canada on FSC-certified ancient-forest-free paper (100% post-consumer recycled) that is processed chlorine- and acid-free. 978-0-7748-2757-7 (bound); 978-0-7748-2759-1 (pdf); 978-0-7748-2760-7 (ePub) Cataloging-in-publication for this book is available from Library and Archives Canada. UBC Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for our publishing program of the Government of Canada (through the Canada Book Fund), the Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens Set in Minion, Calibri, and Kozuka Gothic by Artegraphica Design Co. Ltd. Copy editor: Steph VanderMeulen Proofreader: Helen Godolphin Indexer: Dianne Tiefensee UBC Press The University of British Columbia 2029 West Mall Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z2 www.ubcpress.ca Sample Material © 2014 UBC Press Contents Acknowledgments / vii 1 Where We Are in Indigenous Education / -

What Does a Culturally Responsive Indigenous Teacher Candidate's

WHAT DOES A CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE INDIGENOUS TEACHER CANDIDATE’S EXTENDED PRACTICUM LOOK LIKE: PERSPECTIVES OF COLLEGE FIELD SUPERVISORS AND ADMINISTRATORS A Dissertation submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Educational Administration University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Margaret Leslie Martin © Copyright Margaret Leslie Martin, August, 2020. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctoral Degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department of Educational Administration or the Dean. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without written permission from the author. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to the author and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or make use of materials in this dissertation, in whole or in part, should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Educational Administration University of Saskatchewan 28 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 0X1 Canada OR Dean College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Saskatchewan 116 Thorvaldson Building, 110 Science Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5C9 Canada i ABSTRACT To increase the educational success of Indigenous students and work towards a just society, it is essential to increase the presence of Indigenous teachers within the teaching profession and school systems in Saskatchewan. -

![TITLE: Cameco Corporation: Uranium Mining and Aboriginal Development in Saskatchewan[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7205/title-cameco-corporation-uranium-mining-and-aboriginal-development-in-saskatchewan-1-1677205.webp)

TITLE: Cameco Corporation: Uranium Mining and Aboriginal Development in Saskatchewan[1]

This case was written by Saleem H. Ali for the purpose of entering the 2000 Aboriginal Management Case Writing Competition. TITLE: Cameco Corporation: Uranium Mining and Aboriginal Development in Saskatchewan[1] The Setting The topic of Bernard Michel's speech was general in nature, yet quite specific in substance: "Corporate Citizenship and the Saskatchewan Uranium Industry." He had been invited by the Uranium Institute in London, UK to share his company's experiences in negotiating agreements with Native communities in Northern Saskatchewan. As the President and Chief Executive Officer of Cameco, the world's largest uranium mining company, his speech was much anticipated by the audience. The Uranium mines of Saskatchewan are an interesting laboratory for the study of corporate community relations......The community relations programme's first action was to listen through public hearings to the communities' expressed concerns.......Today 80% of Saskatchewan's residents, compared with 65% in 1990, support continued uranium mining. This reflects the industry's community relations initiative. Cameco's shares also trade at 3.5 times their 1991 issue price. Only a small segment of anti-nuclear activists takes a negative view. Relationships with local communities, like uranium ore, are a valuable resource needing competent development.[2] Originally from France, and a graduate of the Ecole Polytechnique in Paris, Michel, had spent the past two decades in Canada working for various mining interests. Having served as Senior Vice President, Executive Vice President and President for a subsidiary of the French nuclear conglomerate Cogema, Amok Ltd, Michel had eminent credentials to join Cameco in 1988. -

1-24 Journal

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF SASKATCHEWAN Table of Contents Lieutenant Governor ..................................................................................................................... i House Positions ............................................................................................................................. i Members of the Legislative Assembly ............................................................................... ii to iii Constituencies represented in the Legislative Assembly ..................................................... iv to v Cabinet Ministers ........................................................................................................................ vi Committees, Standing, Special and Select ......................................................................... vii to ix Proclamation ................................................................................................................................ 1 Daily Journals ................................................................................................................... 3 to 346 Questions and Answers – Appendix A ....................................................................... A-1 to A-67 Bills Chart – Appendix B .............................................................................................. B-1 to B-7 Sessional Papers Chart, Listing by Subject – Appendix C ......................................... C-1 to C-27 Sessional Papers Chart, Alphabetical Listing – Appendix D .................................... -

Winhec Journal

WINHEC JOURNAL Special Issue INDIGENOUS VOICES: INDIGENOUS CULTURAL LEADERSHIP Issue 1, NOVEMBER 2019 World Indigenous Nations Higher Education Consortium (WINHEC) Navajo Technical University, P.O. Box 849, Crownpoint, New Mexico 87313; Ph: 505.786.4112. Website: www.winhec.org Copyright © 2019 Copyright to the Papers in this Journal reside at all times with the named author/s and if noted their community/family/society. The author/s assigned to WINHEC a non-exclusive license to publish the documents in this Journal and to publish this document in full on the World Wide Web at www.win-hec.org.au. Further use of this document shall be restricted to personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. Any other usage is prohibited, without the express permission of the authors. ISSN: 1177 - 1364 ON-LINE ISSN: 1177 - 6641 Editor-in-Chief Paul Whitinui (Ngā Puhi, Te Aupōuri, Ngāti Kurī, Pākehā) – The School of Exercise Science, Physical and Health Education, University of Victoria, BC, Canada [email protected] Art Work The cover of this WINHEC Journal displays the S’YEWE legend pole designed and carved by Charles W. Elliot (TEMOSEN), Tsartlip, Coast Salish. The history pole was first raised in 1990 to mark the Learned Societies conference at the University of Victoria. Due to water damage the pole was taken down for repairs and over time was fully restored. On September 12, 2017 the pole was rededicated in a ceremony and as part of the University of Victoria Indigenous week of welcome. -

The Life Long Process of Growing Cree and Metis Children

OPIKINAWASOWIN: THE LIFE LONG PROCESS OF GROWING CREE AND METIS CHILDREN By LEAH MARIE DORION Integrated Studies Project submitted to Dr. Winona Wheeler in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta September 30, 2010 ABSTRACT This research project explores Cree and Metis Elders teachings about traditional child rearing and investigates how storytelling is used to facilitate the transfer of this culturally based knowledge. This project examines the concept of Opikinawasowin which contains the Cree philosophical framework for growing children. Opikinawasowin, translates into English as the „child rearing way‟ and is a highly valued aspect of traditional Cree life. For generations Cree and Metis people used storytelling to actualize the teachings of Opikinawasowin. The concept of Opikinawasowin in this study is defined and expressed through Cree and Metis Elders points of view and by the sharing of traditional teachings. Storytelling is used by Elders to impart core values and beliefs about parenting. Through stories Elders give specific teachings relating to how individuals, families, and communities are expected to practice traditional child rearing. Additionally, Opikinawasowin knowledge is often transmitted through the cultural context of prayer and ceremony so asking Elders about the spiritual foundation of Opikinawasowin is an important aspect within this research. This study documents thirteen traditional parenting teachings and identifies fifty four recommendations for further discussion regarding the revival of traditional parenting teachings and practices in our contemporary families and communities. Some issues raised in this study include the need to restore male and female balance in our families, communities, and nation so that our children will have this balance role modeled for them because it is an original feature of traditional society. -

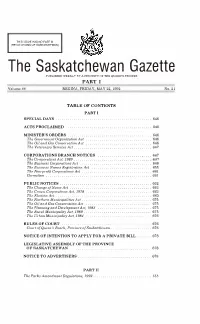

The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY by AUTHORITY of the QUEEN's PRINTER PART I

THIS ISSUE HAS NO PART Ill (REGULATIONS OF SASKATCHEWAN) The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY AUTHORITY OF THE QUEEN'S PRINTER PART I Volume 88 REGINA, FRIDAY, MAY 22, 1992 No. 21 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I SPECIAL DAYS ................................................ 646 ACTS PROCLAIMED .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 646 MINISTER'S ORDERS .......................................... 646 The Government Organization Act .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 646 The Oil and Gas Conservation Act .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 646 The Veterinary Services Act ....................................... 647 • ---; CORPORATIONS BRANCH NOTICES ........................... 647 I The Co-operatives Act, 1989 ..................................._. _,_ __ 6_47 The Business Corporations Act .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 648 , The Business Names Registration Act .............................. 655 The Non-profit Corporations Act ................................... 661 Correction ....................·................................. 661 PUBLIC NOTICES ..................... , ........................ 662 The Change of Name Act ......................................... 662 The Crown Corporations Act, 1978 ................................. 662 The Election Act . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 663 The NorthernMunicipalities Act ................ , .................. 675 The Oil and Gas Conservation Act ................................. 675 The Planning and Development Act, 1983 ........................... 675 The Rural Municipality Act, 1989 ................................. -

June 26, 2001 Health Care Committee 19 Service? That Would Too Fair for Everyone Involved

Standing Committee on Health Care Hansard Verbatim Report No. 3 – June 26, 2001 Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan Twenty-fourth Legislature STANDING COMMITTEE ON HEALTH CARE 2001 Judy Junor, Chair Saskatoon Eastview Hon. Jim Melenchuk, Vice-Chair Saskatoon Northwest Brenda Bakken Weyburn-Big Muddy Hon. Buckley Belanger Athabasca Bill Boyd Kindersley Rod Gantefoer Melfort-Tisdale Warren McCall Regina Elphinstone Andrew Thomson Regina South Published under the authority of The Honourable P. Myron Kowalsky, Speaker STANDING COMMITTEE ON HEALTH CARE 17 June 26, 2001 The committee met at 10:02. agree that quality health care was good in those rural communities. The Chair: — Good morning. If the members are ready, we’ll begin our hearings. The Standing Committee on Health Care’s Anyways for background, Canora is a growing, prosperous first order of business is to receive responses to the Fyke community of about 2,500. We have an economy based largely Commission. on agriculture, not unlike other Saskatchewan communities. Currently we are having great success in diversifying our local Our first presenter this morning is from the town of Canora. Mr. economy as well as supporting value-added industries. Mr. Dutchak, would you take a seat here please. Anywhere, sure. Contrary to some beliefs, we’re not rolling over and dying — quite the contrary — we’re experiencing growth. In fact our I’ll introduce the members of the committee and then you can population has increased by over 8 per cent since 1996. We introduce yourself for the record. I’m Judy Junor. I’m the MLA currently have two schools educating about 500 students in the (Member of the Legislative Assembly) from Eastview, area, a community college, a swimming pool, a civic centre, a Saskatoon Eastview, and I’m chairing the Standing Committee community centre, a curling rink, nearby high throughput on Health Care. -

2-24 Journal

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF SASKATCHEWAN Table of Contents Lieutenant Governor ..................................................................................................................... i House Positions ............................................................................................................................. i Members of the Legislative Assembly ............................................................................... ii to iii Constituencies represented in the Legislative Assembly ..................................................... iv to v Cabinet Ministers ........................................................................................................................ vi Committees, Standing, Special and Select ......................................................................... vii to ix Proclamation ................................................................................................................................ 1 Daily Journals ................................................................................................................... 3 to 304 Questions and Answers – Appendix A ....................................................................... A-1 to A-73 Bills Chart – Appendix B .............................................................................................. B-1 to B-5 Sessional Papers Chart, Listing by Subject – Appendix C ......................................... C-1 to C-25 Sessional Papers Chart, Alphabetical Listing – Appendix D .................................... -

Windspeaker February 15, 1991

i - ;à; x; f F 25 I991 L( 6 N:s & o% Twins reunited with natural family ... page 9 Native Education .. age 12 February 15, 1991 North America's Leading Native Newspaper Volume 8 No. 23 'Supremacist' charged in shooting By Amy Santoro A Wahpeton band member believe LaChance provoked the Manslaughter is homicide in Windspeaker Staff Writer says she's "outraged" by the incident in anyway because "he which the death can be attrib- shooting. Debra Standing says wasn't violent." uted but the intent to kill can't be PRINCE ALBERT, SASK. when some of her Native friends Demkiw says police were proven. entered Nerland's shop "just to unable to prove an intent to kill. Demkiw says it's believed Heather Andre The leader of a Saskatchewan look around," they were told to "The facts we gathered were Nerland also uses the name of white supremacist group has get out or "they'd get a licking." sufficient for a manslaughter Maj. -Gen. Kurt Meyer, a Second Ryan Houle of St. Sophia been charged with manslaughter School in Edmonton Arcand is angered the attor- charge. The intention to kill was World War German SS general in the shooting death of a Native ney general's office charged not there." found guilty of murdering three man. Nerland with manslaughter in- Under the Criminal Code of After four years behind bars Carney Milton Nerland, 26, stead of murder. Arcand, who Canada, a murder charge is laid please see p. 2 for a murder he says he Saskatchewan head of the knew the victim, says he doesn't when the intent to kill is present. -

Afflual REPORT April 1,2003 - March 31,21 Cover Photo Captions

SASKATCHEWAN ARCHIVES BOARD AfflUAL REPORT April 1,2003 - March 31,21 Cover Photo Captions Fig. 1. (Top). A research client using the Archives' reading room, Regina. Fig. 2. (Centre). Official opening of the Kiel Letter Exhibit, Regina, June 20, 2004. (1. to r.) Chris Gebhard, Saskatchewan Archives; Keith Goulet, MLA for Cumberland; Hon. Ralph Goodale, Minister of Finance, Canada; Hon. Joanne Crofford, Minister Responsible for the Saskatchewan Archives Board; Dr. Ian E. Wilson, Archivist and Librarian of Canada. Fig. 3. (Bottom). Conservator Cynthia Ball assessing a portion of the Saskatchewan Archives' photograph collection with the assistance of staff archivist Tim Novak. TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter of Transmittal 1 2003/2004 Highlights 2 A Brief History of the Saskatchewan Archives 2 Role of the Saskatchewan Archives 4 Vision, Mission and the Constitutive Values of the Saskatchewan Archives 4 Structure and Reporting Relationship 6 Organization 8 Renewal of the Saskatchewan Archives 10 Management of Government Information 11 Collection Development and Management 13 Preservation Management and Accommodation 16 Records Storage, Environment and Security 19 Archival Inventory, Arrangement, and Description 20 Descriptive Standards 22 Public Service & Outreach 23 Reference Services 24 Access, Privacy & Legislative Compliance 28 Information Technology 29 Saskatchewan History 30 Report of Management 33 Financial Statements 35 Additional Supplementary Information 44 Letters of Transmitted The Honourable Lynda Haverstock Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan Your Honour: I have the honour of submitting the annual report of the Saskatchewan Archives Board for the period April 1, 2003 to March 31, 2004. Respfectfully submitted-^ . ^.^ The fjonourable Joan Beatty Minister Responsible for the Saskatchewan Archives Board The Honourable Joan Beatty Minister Responsible for the Saskatchewan Archives Board Madam: I have the honour of submitting the annual report of the Saskatchewan Archives Board for the period April 1, 2003 to March 31, 2004. -

New Horizons: NORTEP-NORPAC Stories of Personal and Professional Transformation–Since 1977

NEW HORIZONS: NORTEP-NORPAC STORIES OF PERSONAL AND PROFESSIONAL TRANSFORMATION SINCE 1977 By Dr. Michael Tymchak, Carmen Pauls Orthner, and Shuana Niessen 40TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION ORPAC NORTEP-N Northern Teacher Education Program-Northern Professional Access College 40th Anniversary Edition 40TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION Cover Photo by Sharon Feschuk Other Photography credits: Herman Michell, Carmen Pauls Orthner, and Sharon Feschuk Layout and Design: Shuana Niessen Note: Some interviews for this document were conducted in 2006. Since then, some of the circumstances of those interviewed may have changed. SENIOR ADMINISTRATIVE AND ACADEMIC STAFF DR. HERMAN MICHELL–PRESIDENT/CEO JENNIFER MALMSTEN–VICE PRESIDENT OF LAURA BURNOUF–FACULTY MEMBER ADMINISTRATION Herman has been with NORTEP- Jennifer joined NORTEP-NORPAC When Laura began her work at NORPAC since the fall of 2010. He is in 1997 to become the Secretary NORTEP-NORPAC 20 years ago, her originally from the small fishing and Treasurer. More recently her position first appointment was to teach the trapping community of Kinoosao on has evolved into that of Vice-President non-fluent Cree class. Since then, the eastern shores of Reindeer Lake. (Administration). Over the course Laura has engaged in many studies He speaks fluent Cree (‘th’ dialect) of her nearly 20 year tenure with about how people acquire language. and also has Inuit, Dene, and Swedish the organization, Jennifer has seen In 1999, Laura was supported in her ancestry. Herman has been involved many changes. When she first came desire to take graduate level courses in Aboriginal education in different to NORTEP-NORPAC, the students at the University of Arizona.