Written Evidence from Stephen Davies About Me I Am a Criminal Defence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Payment Date Total Net Amt Supplier Name

PAYMENT_DATE TOTAL_NET_AMTSUPPLIER_NAME RESPONSIBILITY_DESC SUBJECT_DESC INFORMATION SERVICES - IT 31-MAY-2012 604,122 VIRGIN MEDIA BUSINESS PROJECTS - IT RENTALS 06-JUL-2012 407,387 NPIA CENTRAL FINANCING ACTIVITIES PNC - WMPA CONTRIBUTION 17-JUL-2012 407,387 NPIA CENTRAL FINANCING ACTIVITIES PNC - WMPA CONTRIBUTION INFORMATION SERVICES - IT 25-MAY-2012 375,060 SEPURA LTD PROJECTS - IT SPECIAL EQUIPMENT 19-JUN-2012 369,796 HOME OFFICE QUEST PROJECT CONSULTANTS FEES INFORMATION SERVICES - IT 29-JUN-2012 354,253 ORACLE CORPORATION UK LTD PROJECTS - IT SOFTWARE LICENCES 29-JUN-2012 281,010 SCC PLC CMPG - EXTERNALLY FUNDED PURCHASE OF EQUIPMENT 22-JUN-2012 246,630 APPLIED LANGUAGE COMMUNITY JUSTICE AND CUSTODY INTERPRETERS FEES INFORMATION SERVICES - IT 17-APR-2012 227,710 NORTHGATE MANAGED SERVICES PROJECTS - IT BOUGHT IN SERVICES INFORMATION SERVICES - IT 10-AUG-2012 222,288 AIRWAVE SOLUTIONS PROJECTS - IT BOUGHT IN SERVICES INFORMATION SERVICES - IT 15-MAY-2012 201,092 BRITISH TELECOM PROJECTS - IT RENTALS 20-JUL-2012 200,935 CANON (UK) LTD CENTRAL FINANCING ACTIVITIES PHOTOCOPYING CONTRACTS INFORMATION SERVICES - IT 13-APR-2012 196,781 SCC PLC PROJECTS - IT BOUGHT IN SERVICES 09-OCT-2012 196,085 ACPO COMMAND TEAM ACPO SUPPORT CONTRIBUTIONS 03-AUG-2012 170,025 SINGH, SINGH & KAUR PROPERTY BUILDING UTILITIES / RENTS RENTAL OF PREMISES INFORMATION SERVICES - IT 09-OCT-2012 160,751 NORTHGATE INFO. SOL. U.K. LTD PROJECTS - SOFTWARE SUPPORT & MATERIALS 29-JUN-2012 151,754 TELENT TECHNOLOGY SERVICES LTD CMPG - EXTERNALLY FUNDED MAINTENANCE / -

ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2018 President’S Foreword I Was Flattered to Be Invited to Speak on the 70Th for Professionals in the UK

S ANNUAL REPORT 2018 President’s Foreword I was flattered to be invited to speak on the 70th for professionals in the UK. The Society is extremely fortunate to have Linden Thomas and Inez Brown in the anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Thank you for the honour of electing me to be the President of Birmingham Law wings as its next Presidents. Linden has exciting plans rights at the Opera in Lyon. We have a historically good Society and to share the bi-centennial year with my colleague and friend Andrew for the Society in her year and I wish her every relationship with the Lyons Bar cultivated by the hard Beedham. success. work of my hosts Tim Hughes, Maite Roche and the When I opened my year on 24 April 2018 I indicated that I had a number of Batonnier of Lyons. They noted that I have never been James Turner aspirations during my year. I aimed to promote Birmingham as a centre of legal shy to speak up on issues of social justice and human President excellence, improve member engagement, build on our national and international rights. The event was held during the Fete des relationships and ensure we celebrated our bi-centenary in style. A year proves to Lumieres which would be reason enough to spend a be a short time but I am confident that I made progress with all of those aspirations. weekend in a beautiful city. I will not quickly forget a In particular I hope the Society’s members will agree annual cricket competition to be jointly branded with memorable event at which I shared a stage with that we marked the bi-centenary with style. -

1 LEAP MEMBERSHIP February 2013 Catharine Almond Is a Lawyer At

LEAP MEMBERSHIP February 2013 Catharine Almond is a lawyer at Sheehan & Partners, www.sheehanandpartners.ie, qualified in both England and Ireland. She has extensive experience with judicial review, extradition, and the European Arrest Warrant system. Liesbeth Baetens works at Faber Inter, www.faberinter.be, Brussels, in the fields of commercial law, contract law, and criminal law. Previously she was a Junior Researcher at the Department of Criminal Law and Criminology of the Law Faculty of the University of Maastricht, and has worked alongside Professor Taru Spronken in recent studies on procedural safeguards. Wouter van Ballegooij was until mid-2009 the Justice and Home Affairs Policy Adviser to Baroness Sarah Ludford MEP. He is now Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) policy adviser for the Greens/EFA alliance in the European Parliament, www.europarl.europa.eu . Wouter has published several articles on mutual recognition instruments including the European Arrest Warrant and is completing a PhD on mutual recognition with Professor Taru Spronken (Maastricht University) Rodrigo Barbosa Souto is a Portuguese criminal lawyer and a partner in the Lisbon firm F. Castelo Branco & Associados, www.fcb-legal.com. Rachel Barnes is a barrister at Three Raymond Buildings, London, www.3raymondbuildings.com. Rachel is a dual-qualified US attorney and English barrister specialising in international law and cross-border matters. Rachel is also a Visiting Lecturer at the London School of Economics and a consultant editor of the Lloyd’s Law Reports: Financial Crime. Jodie Blackstock is a barrister and the senior legal officer for EU Criminal Justice and Home Affairs at JUSTICE, www.justice.org.uk. -

Policing and Prosecution Conference 2011 the Changing Landscape Tuesday 29 November 2011, London

EARN 6 CPD HOURS REUTERS/Toby Melville POLICING AND PROSECUTION CONFERENCE 2011 THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE TUESDAY 29 NOVEMBER 2011, LONDON Ensure that you are fully up to date with the latest developments in policing, investigation and prosecution of crime including: • Elected Police and Crime Commissioners • Changes to bail, remand and legal aid • Amendments to the PACE codes • Application of corporate manslaughter legislation to cases of death in police custody • Retention of DNA and duties to protect victims and witnesses • Reviews of disclosure in criminal cases POLICING AND PROSECUTION CONFERENCE 2011 TUESDAY 29 NOVEMBER 2011, GRAND CONNAUGHT ROOMS, 61-65 GREAT QUEEN STREET, LONDON WC2B 5DA Policing and the prosecution of crime WHAT DO THESE DRAMATIC CHANGES WILL YOU BENEFIT FROM ATTENDING? has never been so high-profile or MEAN FOR PRACTITIONERS AND If your work requires any knowledge of the so controversial. From legislation POLICY-MAKERS? law relating to policing or the prosecution implementing new arrangements for • Policing the streets – from political of offences, this conference is the ideal police accountability, through measures protest to urban disorder, what is new forum for ensuring you are fully up to date designed to save money in an era of in this perennially controversial field? with developments in these fast-moving austerity, to important new case-law – a • Protecting victims and witnesses – how and controversial areas. Attendance will fundamentally new landscape is emerging. do key recent cases affect the law? be -

LAPG Announces Legal Aid Lawyer of the Year Awards 2021 Finalists

PRESS RELEASE - 19 May 2021 LAPG announces Legal Aid Lawyer of the Year awards 2021 finalists A housing barrister who is playing a leading role in challenging 'No DSS' landlords; and a solicitor who defended the parents of 'Jihadi Jack' Letts, have been honoured by this year's LALY awards judges. The pair are among 26 individuals and nine organisations chosen as finalists in the Legal Aid Practitioners Group 2021 Legal Aid Lawyer of the Year awards. 2021 sees the introduction of a new Disability Rights award: finalists selected for this inaugural award are: Amy Butler, Atkins & Palmer; Kate Jackson, MJC Law; and Kirsty Stuart, Irwin Mitchell. Organisations shortlisted this year cover a wide geographical spread, including: Watkins & Gunn, in Cardiff; Law Centre Northern Ireland, in Belfast; Family Law Company, in Exeter; and Cartwright King, in the Midlands. Chris Minnoch, CEO of LAPG, which organises the LALY awards on a not-for-profit basis to celebrate the work of social justice lawyers, says: ‘This year's finalists give an insight into the range, depth and breadth of the incredible life- changing work that social justice lawyers do - and the vital role they play in ensuring access to justice for individuals, families and communities. It is testimony to the importance of the LALY awards to the legal aid sector that we had a bumper crop of compelling and inspiring nominations this year - despite the extreme pressures we are all facing due to the pandemic.’ Finalists in the Legal Aid Barrister category are: Tessa Buchanan (Garden Court Chambers), recognised for a run of cases establishing that banning DSS tenants is discriminatory against women and disabled people; Blinne Ní Ghrálaigh (Matrix Chambers), who helped overturn the convictions of the 'Stansted 15' protestors; and Stephen Lue (Garden Court Chambers), praised for his skilful handling of complex child abduction cases. -

All Notices Gazette

ALL NOTICES GAZETTE CONTAINING ALL NOTICES PUBLISHED ONLINE ON 21 FEBRUARY 2017 PRINTED ON 22 FEBRUARY 2017 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY | ESTABLISHED 1665 WWW.THEGAZETTE.CO.UK Contents State/2* Royal family/ Parliament & Assemblies/ Honours & Awards/ Church/ Environment & infrastructure/3* Health & medicine/ Other Notices/9* Money/ Companies/10* People/81* Terms & Conditions/117* * Containing all notices published online on 21 February 2017 STATE STATE STATE APPOINTMENTS 2719719DEPUTY LIEUTENANT COMMISSIONS SURREY LIEUTENANCY Her Majesty’s Lord-Lieutenant of Surrey, Mr Michael More- Molyneux, has appointed the following to be Deputy Lieutenants of Surrey: John Anthony Victor Townsend of Cranleigh, Surrey Max Lu of Guildford, Surrey Timothy Wates, of Ewhurst,Surrey The Commissions will be signed on 20 February 2017 Mrs Caroline Breckell MVO DL Assistant Clerk to the Surrey Lieutenancy (2719719) 2 | CONTAINING ALL NOTICES PUBLISHED ONLINE ON 21 FEBRUARY 2017 | ALL NOTICES GAZETTE ENVIRONMENT & INFRASTRUCTURE Please note that any comments which you make to an application cannot generally be treated as confidential. All emails or letters of ENVIRONMENT & objection or support for an application, including your name and address require to be open to public inspection and will be published on the Council’s website. Sensitive personal information such as INFRASTRUCTURE signatures, email address and phone numbers will usually be removed. Lindsay Freeland ENERGY Chief Executive www.southlanarkshire.gov.uk (2719530) 2717324FALCK RENEWABLES WIND LIMITED -

Husnara Begum Amanda Jardine-Viner

22/03/2018 Careers: Preparing mature students and career changers for the solicitors’ profession Sponsored by Wednesday 21 March 2018 Husnara Begum Career Strategist / Coach, Husnara Begum Consulting Amanda Jardine-Viner Trainee Solicitor, Buss Murton 1 22/03/2018 Training routes to qualification Diane Goodier Head of Students, University of Law Why choose a career in law? • Intellectually stimulating and challenging • Variety of practice areas • Job satisfaction • Career progression • Financially rewarding Training routes Qualifying degree in Training Legal Admission Contract English Law Solicitor Practice as a solicitor 2 years Course Non-Law degree Bar Professional Call to Pupillage Graduate Barrister Training the Bar 12 months Diploma in Law Course 2 22/03/2018 Funding options • Sponsorship by future employer • Loans – – Government funded (masters’ programmes) – Commercial Providers • Scholarships and bursaries The SRA’s plan is to replace the LPC as the route into the profession 2. SQE Stage 1 3. Qualifying Work Very limited skills content Experience No electives 4. SQE Stage 2 Expected that SQE1 is sat Must pass all of SQE1 before work-based before attempting experience SQE2 SQE2 is taken 1. Entry 3 during/following work- based learning Entrance are graduates, 2 4 solicitor apprentices and foreign qualified lawyers 1 SQE 5 5. Qualification No definition of a Qualifying Law Degree No prescribed non-law conversion course 8 Solicitor Apprenticeship Qualfication Type of Student Solicitor Apprenticeship with How long does it last? LLB (Law Degree) in Legal 3 A Levels A-C Practice & Skills 6 year programme 5 GCSE’s including Maths & & September & January starts English or equivalent Preparation for SQE 1 & 2 How does it work? Employers 80% work- 20% study and Plexus training Ulaw materials – i-LLB (canvas) Training Fletchers Ulaw subject tutors Ulaw WBA assessor visits the Gowling WLG apprentice every 10- 12 Ulaw WBA weeks to check progress and Exeter City Council Admin Support build a work based portfolio. -

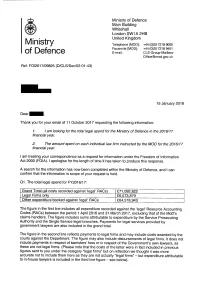

Broken Down Cost of MOD Total Legal Spend for Financial Year 2016 to 2017

Companies Grand Total A LEEDS DAY SOLICITORS £ 4,458 ADDLESHAW GODDARD LLP £ 188,376 AEGIS LEGAL LIMITED £ 4,994 ALLEN & OVERY LLP £ 1,541 AMELANS SOLICITORS £ 4,370 AMV LAW LIMITED £ 8,148 ANTONIS K KARAS LLC £ 961 BALFOUR + MANSON LLP £ 22,500 BCL BURTON COPELAND £ 83 BEACHCROFTS LLP £ 9,159 BEETZ & PARTNER £ 340 BENDALL & SONS £ 8,914 BERRYMANS LACE MAWER LLP £ 99,957 BIRD + LOVIBOND SOLICITORS £ 68,379 BLAKE LAPTHORN £ 2,500 BLAKE MORGAN LLP £ 6,325 BOND DICKINSON LLP £ 264 BOWER & BAILEY LLP £ 20,000 BROWNE JACOBSON LLP £ 750 BURGES SALMON LLP £ 621,378 CHRYSSES DEMETRIADES & CO LLC £ 17,857 CLARKE WILLMOTT LLP £ 14,540 CLYDE & CO LLP £ 12,500 COODES LLP £ 5,560 CORDELL & CO SOLICITORS £ 15,853 CORKERBINNING £ 97,035 CROMBIE WILKINSON SOLICITORS LLP £ 14,303 D J MACKAY AND PARTNERS LLP £ 5,815 DAC BEACHCROFT CLAIMS LIMITED £ 36,413 DAVITT JONES BOULD LTD £ 9,888 DENTONS UKMEA LLP £ 40,843 DEVONSHIRES SOLICITORS £ 329,479 DIGBY BROWN LLP £ 12,400 DLG LEGAL SERVICES LIMITED £ 5,355 DWF LLP £ 3,375 EAD SOLICITORS LLP £ 3,800 EDWARDS PATENT SERVICES LTD £ 77 ELLISONS SOLICITORS £ 33,757 EVERSHEDS LLP £ 6,780 FALKLAND ISLANDS LEGAL SERVICES LTD £ 1,740 FETHERSTONHAUGH & CO £ 4,153 FLINT BISHOP SOLICTORS £ 825 FORSTER DEAN LIMITED £ 19,100 FRANCIS HANNA & CO SOLICITORS £ 5,626 FRESHFIELDS BRUCKHAUS DERINGER LLP £ 221,650 GARD & CO SOLICITORS £ 1,000 GIRLINGS PERSONAL INJURY CLAIMS LIMITED £ 9,758 GRAYSONS SOLICITORS £ 5,251 GREAVES BREWSTER £ 5,822 HAMILTON HARRISON & MATHEWS £ 26,828 HARDING EVANS LIMITED LIABILITY PARTNERSHIP £ 5,000 -

Investigations, Compliance & Insurance

2020-2021 EDITION Intelligence Report & Rankings INVESTIGATIONS, COMPLIANCE & INSURANCE Top law firms and expert firms Exclusive interviews with leaders Insights & analysis Anton Carniaux Besma Boumaza Marcelo Zenkner Biba Homsy Rafael Ramírez Cruz Samsung Accor Petrobras OpenVASP AXA Association P. 17 P. 18 P. 20 P. 26 P. 29 Strategic Information for Top Executives INTERNATIONAL COLLECTION 2020-2021 EDITION Intelligence Report & Rankings LITIGATION & ARBITRATION Top law firms, expert firms & litigation funders Exclusive interviews with leaders Commandez l’ensembleInsights & analysis de nos guides sur eshop.leadersleague.com Claudia Salomon Eric Blinderman Pierre Amariglio Carolina Mouraz Gary Birnberg ICC International Therium Capital Tenor Capital TAP Air Portugal JAMS Court of Arbitration Management Management P. 94 P. 94 P. 94 P. 94 P. 94 Order our Litigation & Arbitration guide at: www.leadersleague.com/en/products Follow us: LeadersLeague Leaders League - 15 Avenue de la Grande Armée - 75116 Paris Subscriptions - Tel: +33 1 43 92 93 56 - [email protected] Advertising - Tel: +33 1 45 02 25 38 - [email protected] EDITORIAL 15, avenue de la Grande-Armée - 75116 Paris Tél. : 01 45 02 25 00 - Fax : 01 45 02 25 01 www.leadersleague.com PUBLISHING DIRECTOR & CEO Pierre-Étienne Lorenceau [email protected] EDITORIAL STAFF Managing Editor Arjun Sajip [email protected] Head of Latin America Jandira Salgado [email protected] ARJUN SAJIP Editors - International Managing Editor Ramata Diallo, Juan -

Upholding Fair Trial Rights Within the European Union

Aldis Alliks (Latvia, VARUL), Catharine Almond (Ireland, Sheehan and Partners), Joao Barroso Neto (Portugal, Carlos Pinto de Abreu), Rachel Barnes (UK, 3 Raymond Buildings), Myrddin Bouwman (Netherlands, Van Appia & Van der Le), Inga Botyriene (Lithuania, I.Botyrienės ir R.A.Kučinskaitės Vilniaus advokatų kontora), Danut-Ioan Bugnariu (Romania, Bugnariu Avocati), Ben Cooper (UK, Doughty Street Chambers), Vania Costa Ramos (Portugal, Carlos Pinto de Abreu), Scott Crosby (Belgium, Kemmler Rapp Böhlke & Crosby), Anand Doobay (UK, Peters and Peters), Robert Eagar (Ireland, Sheehan & Partners), Andrejs Latvia Elksnins (Latvia, S.Varpins and A.Elksnins Law Office), Joanna Evans (UK, S.Varpins and A.Elksnins Law Office), Mike Evans (UK, Kaim Todner), Henry Feltenstein (Spain, Corporate Defense), Hans Gaasbeek (Netherlands, Lawyers without Borders), Cliff Gatzweiler (Germany, Self-Employed), Markku Fredman (Finland, Fredman and Mansson), George Gebbie (UK, Advocates Library), Orestis Georgiadis (Greece, Goulielmos D. And Partners in Thessaloniki), Carlos Gomez-Jara (Spain, Corporate Defence), Edward Grange (UK, Hodge Jones and Allen), Alexandru Grosu (Romania, Grosu & Asociatii Advocats), Fulvia Guardascione (Italy, Studio Legale Vetrano), Arturas Gutauskas (Lithuania, Varul Law Firm), Aurelijus Gutauskas (Lithuania, Justice of the Supreme Court of Lithuania and Academic, Mylokolas Romeris University), Marie Guiraud (France), Sanna Herlin (Sweden, Tre Advokater), John Jones (UK, Doughty Street Chambers), Hans Kjellund (Denmark, Advokaterne Sankt -

Conference Booklet

Redesigning Justice: Promoting civil rights, trust and fairness International conference 21–22 March 2018, Keble College, Oxford 2 Redesigning Justice: Promoting civil rights, trust and fairness Redesigning Justice: Promoting civil rights, trust and fairness International conference 21–22 March 2018, Keble College, Oxford Contents Welcome 4 Conference agenda 5 Conference venue information and map 7 Sponsors and exhibitors 10 Plenary sessions: Speakers’ biographies and abstracts 13 Parallel sessions: Programme and abstracts 25 About the Howard League for Penal Reform 106 Please note that an online version of this booklet is available on the Howard League website at www.howardleague.org 3 Welcome Welcome to the Howard League for Penal Reform’s international conference Redesigning Justice: Promoting civil rights, trust and fairness. We are delighted with the programme and look forward to two days of stimulating debate and discussion here, at Keble College, Oxford. Our relationship with justice is complex. Justice and the systems for delivering (criminal) justice are often criticised but rarely is there a credible, achievable challenge to the status quo proposed: most want to tinker around the edges. We are witnessing a global climate of mistrust and challenge to the establishment, political elites as well as justice leadership. The time is right to consider the way we do justice and what we want the justice system to achieve. The aim of the conference is to bring together academics, policy makers and practitioners from a variety of disciplines to shine a light on seemingly intransigent aspects of justice systems, including what equality and legitimacy mean 50 years after the assassination of Martin Luther King and why prison is still so central to justice responses to crime. -

Greater Birmingham

Greater Birmingham The monthuly publiclatioln oef the Bitrminighan m Law Society BMay/June 2016 New President takes the helm at Birmingham Law Society Legal Awards 2016 BLS Networking Event In Conversation with Andy Street, MD of John Lewis LookingLooking forffoor a simplesimple solution…solution… whywhy notnot ppurchaseurcha legallegal indemnitiesindemniti online?online? Our free residential online service is easy to use. Obtaining quotes and purchasing cover is a few clicks away. RegisterRegister andand ggetet startedstart today! oror ccallall 020020 72567256 33847847 UUnablenable ttoo mmeeteet ourour self-issueselff--issue ccriteriariteria oorr needneed covercover forffoor newnew builds,builds, developmentdevelopment oror commercialcommercial risks?risks? OOurur bbespokeespoke uunderwritingnderwriting tteameam hhaveave tthehe eexpertisexpertise ttoo aassistssist yyou,ou, ppleaselease eemailmail [email protected]@crminsurance.co.uk Premiums correct at date of publication. Conveyancing Risk Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered No. 04568951. Registered O4ce: 150 Aldersgate Street, London EC1A 4AB. Greater Birmingham Birmingham Law Society Suite 101 ulletin Cheltenham House 14-16 Temple Street B4. News from the President Birmingham B2 5BG DX 13100 Birmingham 1 0121 227 8700 6. AGM 2016 Published by 10. Birmingham Law Society Board Baskerville Publications 25 Southworth Way 14. The Legal Awards 2016 Thornton Cleveleys Lancashire FY5 2WW Editorial Enquiries and 21. Birmingham Law Society Debating Competition Advertising Sales Julia Baskerville 01253 829431 24. In conversation with Andy Street [email protected] [email protected] www.locallawsocietypublications.co.uk 36. St Philips Barristers join forces to raise over £2,500 The views and opinions expressed in The Bulletin are for ER Mason Youth Centre those of the individual contributors and not those of the Birmingham Law Society.