AUTHOR Robin, John P.; Terzo, Frederick C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epidemiology of Dog Bite Incidents in Chile: Factors Related to the Patterns of Human-Dog Relationship

animals Article Epidemiology of Dog Bite Incidents in Chile: Factors Related to the Patterns of Human-Dog Relationship Carmen Luz Barrios 1,2,*, Carlos Bustos-López 3, Carlos Pavletic 4,†, Alonso Parra 4,†, Macarena Vidal 2, Jonathan Bowen 5 and Jaume Fatjó 1 1 Cátedra Fundación Affinity Animales y Salud, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, Parque de Investigación Biomédica de Barcelona, C/Dr. Aiguader 88, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 2 Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Mayor, Camino La Pirámide 5750, Huechuraba, Región Metropolitana 8580745, Chile; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Ciencias Básicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Santo Tomás, Av. Ejército Libertador 146, Santiago, Región Metropolitana 8320000, Chile; [email protected] 4 Departamento de Zoonosis y Vectores, Ministerio de Salud, Enrique Mac Iver 541, Santiago, Región Metropolitana 8320064, Chile; [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (A.P.) 5 Queen Mother Hospital for Small Animals, Royal Veterinary College, Hawkshead Lane, North Mymms, Hertfordshire AL9 7TA, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +56-02-3281000 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Simple Summary: Dog bites are a major public health problem throughout the world. The main consequences for human health include physical and psychological injuries of varying proportions, secondary infections, sequelae, risk of transmission of zoonoses and surgery, among others, which entail costs for the health system and those affected. The objective of this study was to characterize epidemiologically the incidents of bites in Chile and the patterns of human-dog relationship involved. The results showed that the main victims were adults, men. -

The Evolution of the Location of Economic Activity in Chile in The

Estudios de Economía ISSN: 0304-2758 [email protected] Universidad de Chile Chile Badia-Miró, Marc The evolution of the location of economic activity in Chile in the long run: a paradox of extreme concentration in absence of agglomeration economies Estudios de Economía, vol. 42, núm. 2, diciembre, 2015, pp. 143-167 Universidad de Chile Santiago, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=22142863007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative TheEstudios evolution de Economía. of the location Vol. 42 of -economic Nº 2, Diciembre activity in2015. Chile… Págs. / Marc143-167 Badia-Miró 143 The evolution of the location of economic activity in Chile in the long run: a paradox of extreme concentration in absence of agglomeration economies*1 La evolución de la localización de la actividad económica en Chile en el largo plazo: la paradoja de un caso de extrema concentración en ausencia de fuerzas de aglomeración Marc Badia-Miró** Abstract Chile is characterized as being a country with an extreme concentration of the economic activity around Santiago. In spite of this, and in contrast to what is found in many industrialized countries, income levels per inhabitant in the capital are below the country average and far from the levels in the wealthiest regions. This was a result of the weakness of agglomeration economies. At the same time, the mining cycles have had an enormous impact in the evolution of the location of economic activity, driving a high dispersion at the end of the 19th century with the nitrates (very concentrated in the space) and the later convergence with the cooper cycle (highly dispersed). -

Report on Cartography in the Republic of Chile 2011 - 2015

REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN CHILE: 2011 - 2015 ARMY OF CHILE MILITARY GEOGRAPHIC INSTITUTE OF CHILE REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN THE REPUBLIC OF CHILE 2011 - 2015 PRESENTED BY THE CHILEAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE INTERNATIONAL CARTOGRAPHIC ASSOCIATION AT THE SIXTEENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE INTERNATIONAL CARTOGRAPHIC ASSOCIATION AUGUST 2015 1 REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN CHILE: 2011 - 2015 CONTENTS Page Contents 2 1: CHILEAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE ICA 3 1.1. Introduction 3 1.2. Chilean ICA National Committee during 2011 - 2015 5 1.3. Chile and the International Cartographic Conferences of the ICA 6 2: MULTI-INSTITUTIONAL ACTIVITIES 6 2.1 National Spatial Data Infrastructure of Chile 6 2.2. Pan-American Institute for Geography and History – PAIGH 8 2.3. SSOT: Chilean Satellite 9 3: STATE AND PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS 10 3.1. Military Geographic Institute - IGM 10 3.2. Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service of the Chilean Navy – SHOA 12 3.3. Aero-Photogrammetric Service of the Air Force – SAF 14 3.4. Agriculture Ministry and Dependent Agencies 15 3.5. National Geological and Mining Service – SERNAGEOMIN 18 3.6. Other Government Ministries and Specialized Agencies 19 3.7. Regional and Local Government Bodies 21 4: ACADEMIC, EDUCATIONAL AND TRAINING SECTOR 21 4.1 Metropolitan Technological University – UTEM 21 4.2 Universities with Geosciences Courses 23 4.3 Military Polytechnic Academy 25 5: THE PRIVATE SECTOR 26 6: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND ACRONYMS 28 ANNEX 1. List of SERNAGEOMIN Maps 29 ANNEX 2. Report from CENGEO (University of Talca) 37 2 REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN CHILE: 2011 - 2015 PART ONE: CHILEAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE ICA 1.1: Introduction 1.1.1. -

Manufacturing Landscape It's a Sunny Morning in Santiago, Chile's Capital. Tamara Pérez and Antonella Mele Are Standing In

Manufacturing Landscape Words Frederico Duarte Photographs Cristóbal Olivares It’s a sunny morning in Santiago, Chile’s capital. Tamara Pérez and Antonella Mele are standing in what was once the dining room of a pretty 1960s apartment building in Providencia, a mainly residential quarter of the Chilean capital. Stood in silence, they are slowly and gently applying a black, grainy substance to a bulky stoneware object placed on the table in front of them. 72 Duarte, Frederico. “Manufacturing Landscape,” Disegno, April 2017. Tamara Pérez examining the lava In the adjacent room – surely a former living room – fabric, as if held by a kind hand. In 2016, three of products in GT2P’s studio, Santiago. the other members of the design studio Great Things these vases were included in the Italian furniture to People (GT2P) sit at laptops, scribbling on a brand Cappellini’s Progetto Oggetto collection, whiteboard-top table, talking on the phone, chatting. and are currently being manufactured in &OHMBOE A breeze flows through the many open windows and The second direction is CPP No2: Porcelain vs Lava doors of the ground-floor apartment, which is Lights, a series of wall lamps and chandeliers for sparsely furnished, and whose somewhat disorderly which GT2P perfected the casting process by rooms reveal models, materials, bits of prototypes, controlling the clay layers and therefore the tools, books, magazines. In one of these rooms a 3D thickness and translucency of the resulting shallow, porcelain printer is being installed. In the kitchen creamy white porcelain bowls. While working on there’s instant coffee and the odd ceramic cup on these lights the studio began to experiment with the counter, another porcelain printer and a kiln, lava samples collected from Chile’s Chaitén and where Pérez and Mele will soon place the object Villarrica volcanoes, performing heating and they have been working on. -

Manual Turf Curvas

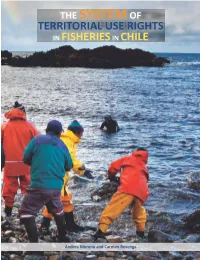

THE SYSTEM OF TERRITORIAL USE RIGHTS IN FISHERIES IN CHILE Manuela Wedgwood Editing Alejandra Chávez Design and Layout Andrea Moreno and Carmen Revenga Cover image: The Nature Conservancy Harvesting of Chilean abalone (Concholepas concholepas) in the fishing village of Huape, in Valdivia, Chile. © Ian Shive, July 2012. With analytical contributions on socio-economic analyses from: Hugo Salgado, Miguel Quiroga, Mónica Madariaga and Miguel Moreno, Citation: Department of Environmental and Natural Resource Economics, Moreno A. and Revenga C., 2014. The System of Territorial Use Rights in Fisheries in Chile, Universidad de Concepción Concepción - Chile The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, Virginia, USA. 88 pp. Copyright © The Nature Conservancy 2014 Published by the Nature Conservancy, Arlington, Virginia, USA Printed in Lima, Peru, on Cyclus Print paper, made from 100% recycled fiber. THE SYSTEM OF TERRITORIAL USE RIGHTS IN FISHERIES IN CHILE Manuela Wedgwood Editing Alejandra Chávez Design and Layout Andrea Moreno and Carmen Revenga Cover image: The Nature Conservancy Harvesting of Chilean abalone (Concholepas concholepas) in the fishing village of Huape, in Valdivia, Chile. © Ian Shive, July 2012. With analytical contributions on socio-economic analyses from: Hugo Salgado, Miguel Quiroga, Mónica Madariaga and Miguel Moreno, Citation: Department of Environmental and Natural Resource Economics, Moreno A. and Revenga C., 2014. The System of Territorial Use Rights in Fisheries in Chile, Universidad de Concepción Concepción - Chile The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, Virginia, USA. 88 pp. Copyright © The Nature Conservancy 2014 Published by the Nature Conservancy, Arlington, Virginia, USA Printed in Lima, Peru, on Cyclus Print paper, made from 100% recycled fiber. TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 FOREWORD 37 3.2.5. -

Observation of Maritime Traffic Interruption in Patagonia During The

remote sensing Communication Observation of Maritime Traffic Interruption in Patagonia during the COVID-19 Lockdown Using Copernicus Sentinel-1 Data and Google Earth Engine Cristina Rodríguez-Benito 1, Isabel Caballero 2 , Karen Nieto 3 and Gabriel Navarro 2,* 1 Mariscope Ingeniería, Puerto Montt 5480000, Chile; [email protected] 2 Instituto de Ciencias Marinas de Andalucía (ICMAN), Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Puerto Real, 11510 Cádiz, Spain; [email protected] 3 Independent Researcher, Guillermo Munnich, 204, Valparaiso 2340000, Chile; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Human mobilization during the COVID-19 lockdown has been reduced in many areas of the world. Maritime navigation has been affected in strategic connections between some regions in Patagonia, at the southern end of South America. The purpose of this research is to describe this interruption of navigation using satellite synthetic aperture radar data. For this goal, three locations are observed using geoinformatic techniques and high-resolution satellite data from the Sentinel-1 satellites of the European Commission’s Copernicus programme. The spatial information is analyzed using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform as a global geographical information system and Citation: Rodríguez-Benito, C.; the EO Browser tool, integrated with several satellite data. The results demonstrate that the total Caballero, I.; Nieto, K.; Navarro, G. maritime traffic activity in the three geographical hotspots selected along western Patagonia, the Observation of Maritime Traffic Chacao Channel, crossing of the Reloncavi Fjord and the Strait of Magellan was totally interrupted Interruption in Patagonia during the during April–May 2020. This fact has relevant repercussions for the population living in isolated COVID-19 Lockdown Using areas, such as many places in Patagonia, including Tierra del Fuego. -

Comparison of Public Perception in Desert and Rainy Regions of Chile Regarding the Reuse of Treated Sewage Water

water Article Comparison of Public Perception in Desert and Rainy Regions of Chile Regarding the Reuse of Treated Sewage Water Daniela Segura 1, Valentina Carrillo 1,2, Francisco Remonsellez 2, Marcelo Araya 1 and Gladys Vidal 1,* ID 1 Engineering and Biotechnology Environmental Group, Environmental Science Faculty & Center EULA–Chile, University of Concepción, P.O. Box 160-C, Concepción 4070386, Chile; [email protected] (D.S.); [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (M.A.) 2 Chemical Engineering Department, Engineering and Geological Science Faculty, Católica del Norte University, P.O. Box 1280, Antofagasta 1240000, Chile; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +56-41-2204-067; Fax: +56-41-2207-076 or +56-041-2661-033 Received: 2 February 2018; Accepted: 12 March 2018; Published: 17 March 2018 Abstract: The objective of this study was to compare the public perception in desert and rainy regions of Chile regarding the reuse of treated sewage water. The methodology of this study consisted of applying a survey to the communities of San Pedro de Atacama (desert region) and Hualqui (rainy region) to identify attitudes about the reuse of sewage water. The survey was applied directly to men and women, 18 to 90 years of age, who were living in the studied communities. The results indicate that inhabitants of San Pedro de Atacama (desert region) were aware of the state of their water resources, with 86% being aware that there are water shortages during some part of the year. In contrast, only 55% of residents in Hualqui (rainy region) were aware of water shortages. -

The Mapuche People: Between Oblivion and Exclusion

n°358/2 August 2003 International Federation for Human Rights Report International Investigative Mission CHILE THE MAPUCHE PEOPLE: BETWEEN OBLIVION AND EXCLUSION I. INTRODUCTION AND PRESENTATION OF THE MISSION . 4 II. CONTEXT . 6 III. FORESTRY EXPLOITATION: THE DESTRUCTION OF A PEOPLE AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT. 10 IV. THE RALCO PROJECT: THE RESISTANCE OF A PEOPLE . 24 V. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS. 41 VI. APPENDIX . 45 VI. BIBLIOGRAPHY . 49 CHILE THE MAPUCHE PEOPLE: BETWEEN OBLIVION AND EXCLUSION INDEX I. INTRODUCTION AND PRESENTATION OF THE MISSION . 4 II. CONTEXT . 6 1. GENERAL FACTS ON THE INDIGENOUS POPULATION . 6 2. THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN CHILE . 8 III. FORESTRY EXPLOITATION: THE DESTRUCTION OF A PEOPLE AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT. 10 1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND ORIGIN OF THE CURRENT CONFLICT. 10 2. REPRESSION OF THE MAPUCHE PEOPLE . 13 3. JUDICIAL PERSECUTION OF LEADERS AND MEMBERS WITHIN THE MAPUCHE COMMUNITIES. 16 4. OTHER CONSEQUENCES OF FORESTRY EXPLOITATION ON THE MAPUCHE PEOPLE. 19 IV. THE RALCO PROJECT: THE RESISTANCE OF A PEOPLE . 24 1. BACKGROUND ON THE RALCO HYDROELECTRIC POWER PLANT . 25 a) Endesa's Mega-Hydraulic Project: Technical and Financial Aspects b) The Pangue Plant, the Pehuén Foundation and Downing-Hair Reports 2. IRREGULARITIES OF FORM AND SUBSTANCE IN THE RALCO CONCESSION . 27 a) Environmental Authorization: The Agreement Between ENDESA and CONOMA b) The Exchange of Pehuenche Land and CONADI's Authorization c) The Illegal Electrical Concession of The Ralco project 3. EFFECTS OF THE RALCO CONSTRUCTION ON THE PEHUENCHES. 34 a) Represssion of the Affected Communities b) The PehuencheS Women4S Resistance V. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS. 41 VI. -

Temuco, Chile

The Forests Dialogue TREE PLANTATIONS IN THE LANDSCAPE INITIATIVE CHILE FIELD DIALOGUE 31 May – 3 June 2016 – Temuco, Chile BACKGROUND PAPER Marcos Tricallotis & Peter Kanowski The Australian National University 1. Introduction: setting the context The Forests Dialogue‟s Scoping Dialogue on Intensively Managed Planted Forests (IMPF) (September 2015, Durban, South Africa) agreed to convene a series of field dialogues to discuss key issues associated with tree plantations, as a particular form of planted forests. The dialogue series was renamed Tree Plantations in the Landscape (TPL) to emphasise its focus, and the landscape context of tree plantations. The Chile TPL Dialogue is the first in this series, and focuses on the unique context and experience of Chile. The Durban Scoping Dialogue agreed on five priority areas for future dialogue about tree plantations 1 (Box 1). Scoping Dialogue participants noted that the particular mix and emphasis of priorities discussed at each field dialogue would depend on its context. Box 1. Priority topic areas for any future dialogue about tree plantations 1. Plantation forests in the context of the global development agenda (as represented, for example, by the Sustainable Development Goals) & megatrends, and in the contexts of development at multiple scales, from global to local. This topic would also include consideration of: . the definition and scope of plantation forests and „IMPF‟, and associated data and reporting issues; . articulation of a shared vision for the roles of plantation forests. 2. The design and implementation of plantation forests in the context of a landscape approach, and at different scales & geographies. This topic includes consideration of approaches to landscape-scale integration of forestry & agriculture, and of meeting multiple demands from and through sustainable productive landscapes. -

Panorama Megacities

Project Document REGIONAL PANORAMA Latin America Megacities and Sustainability Ricardo Jordán Johannes Rehner Joseluis Samaniego Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) The present document was prepared by Joseluis Samaniego and Ricardo Jordán, of the Sustainable Development and Human Settlements Division of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), and by Johannes Rehner, professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Its preparation formed part of Risk Habitat Megacities, a joint project of ECLAC and the Helmholtz Association, represented by the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) of Leipzig, Germany. Production of the document benefited from support from the Networking Fund of the Helmholtz Association and the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) and the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development of Germany. The following persons contributed to the preparation of this document: Sebastián Baeza González, Jorge Cabrera Gómez, Maximiliano Carbonetti, Dirk Heinrichs, Paula Higa, Jürgen Kopfmüller, Kerstin Krellenberg, Margarita Pacheco Montes, Paulina Rica Mery, Iván Moscoso Rodríguez, Claudia Rodríguez Seeger, Humberto Soto and Volker Stelzer. The authors wish to express their gratitude to the following people for their critiques, comments and revision of the document: Jonathan Barton, Klaus-Rainer Bräutigam, Ulrich Franck, Tahnee Gonzalez, Andreas Justen, Henning Nuissl, Gerhard Schleenstein and Peter Suppan. Special thanks are owed to Courtney -

Cesifo Working Paper No. 8177

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Baten, Jörg; Llorca-Jaña, Manuel Working Paper Inequality, Low-Intensity Immigration and Human Capital Formation in the Regions of Chile, 1820-1939 CESifo Working Paper, No. 8177 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Baten, Jörg; Llorca-Jaña, Manuel (2020) : Inequality, Low-Intensity Immigration and Human Capital Formation in the Regions of Chile, 1820-1939, CESifo Working Paper, No. 8177, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/216573 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made -

Addendum for the Update of Chile's Emissions Reduction Program Following the Recommendations from the Chair's Summary at the 1

Addendum for the Update of Chile's Emissions Reduction Program following the Recommendations from the Chair’s Summary at the 15th Meeting of the Carbon Fund National Strategy on Climate Change and Vegetation Resources of Chile (2017-2025) Version N°8, October 2018, Document Prepared by the Climate Change and Environmental Services Unit (UCCSA) National Forestry Corporation (CONAF), Ministry of Agriculture (MINAGRI) Authors • José Antonio Prado. Head of Climate Change and Environmental Services Unit. Forestry engineer and Master of Science in forestry. • Jaeel Moraga. Coordinator of the Forest Carbon Cooperative Fund. Forestry Engineer. Diploma in Environmental Restoration and Rehabilitation. • Daniel Montaner. UCCSA Monitoring Team. Forestry Engineer. Master of Science in remote sensing. 1 Reviews and contributions Professionals Institution Date Angelo Sartori, Javier Cano, and Osvaldo UCCSA and CONAF Professionals Quintanilla Enrique O’Farril, Head of the Department of AGCI, Ministry of Foreign Affairs May 11, 2017 Bilateral and Multilateral Cooperation (OECD Chile Position) Robinson Esparza (Benefits Distribution Independent Consultant September 10, 2017 System) Stavros Papageorgiou and Leonel Iglesias World Bank September 22, and November 9, 2017 Guido Aguilera, Head of the Indigenous and CONAF October 4, 2017 Social Affairs Unit (social co-benefits). Rodrigo Henríquez, Manager, Environmental CONAF October 17, 2017 Audit and Evaluation Management (GEF) (Audit actions included within the area of the Emissions Reduction Program). Rony Pantoja, Head of Wood Energy Unit, CONAF October 19, 2017 Administration of Forest Promotion and Development (GEDEFF) (Firewood usage and articulation with the energy sector included within the area of the Emissions Reduction Program). 2 Contents 1. Chile's position on the Commercial Conditions of the ERPA .....................................................