Chile´S Pathway to Green Growth: Measuring Progress at Local Level

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROSPECCION GEOQUIMICA DE URANIO EN SEDIMENTOS DE DRENAJE .DEL AREA TALCA-CAUQUENES Santiago, Diciembre De 1978. R.L. Moxham Ge

,, PROSPECCION GEOQUIMICA DE URANIO EN SEDIMENTOS DE DRENAJE .DEL AREA TALCA-CAUQUENES ( 5 P • N • U • D • ) . .;f R.L. Moxham Geólogo N.U. P. Valenzuela O. G.eólogo C.CH.E.N Santiago, Diciembre de 1978. I N D I C E l.- INTRODUCCION 1. 1. - General . 1 . 2. - Ubicación¡ y Accesos L3. - Geomorfología y Drenaje 1 . 4. - Método de Trabajo 1.5.- Participantes 1. 6. - ;- Geología Regional 11.- TRATAMIENTO DE LOS DATOS E INTERPRETACION 2. 1 . - Generalizadades 2. 2. - Uranio 2.3.- Radiometría 2. 4. - Relación entre Uranio y Radiometría 2.5.- Cobre / 2. 6. - Zinc ,. 2.7.- Plata 2.8.- Plomo 2.9.- Cobalto 2.10.- Manganeso III.-DISTRIBUCION ESTADISTICA . Y ESPACIAL. DE LOS ELEMENTOS CONSIDERADOS. 3.1.- Abundancia y Parámetros Estadísticos 3 . 2.- Zonación Geoquímica .I IV.- CONCLUSIONES V.- RECOMENDACIONES VI. - REFERENCIAS Indice de Figuras. Fig -Nl: Map~ ·deUbicación y Cobertura. Fig N2: Parámetros Estadísticos deElementos Analizados en Sedi.i1e ntos de Drenaje. ·, Mapas fuera de Texto . N 1: Mapa de Anomalfas de Uranio . N 2: Mapa de Anomalías Radiométricas en Sedimentos de Drenaje. N 3: Anomalías Geoquímicas de Ag-Cu-Zn-Pb en Sedimentos de Drenaje. N 4: Mapa de Sectores Anómalos. 1 1.- INfRODUCCION . - 1. 1. - GENERAL.- El área Talca-Cauquenes , conocida como área S P.N.U.D. (Programa - Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo), fue uno de l os lugares selec cionados por .el Proyecto de Exploración de Uranio en Chi le y pro - puesto como t ~l en el Documento del Proyecto avalado por l a Agen - f cía Internacional de Energía Atómica y la Comisión Chi l ena de Ener gía Nuclear. -

El Comportamiento Demográfico De Una Parroquia Poblana De La Colonia Al México Independiente: Tepeaca Y Su Entorno Agrario, 1740-1850*

EL COMPORTAMIENTO DEMOGRÁFICO DE UNA PARROQUIA POBLANA DE LA COLONIA AL MÉXICO INDEPENDIENTE: TEPEACA Y SU ENTORNO AGRARIO, 1740-1850* Juan Carlos GARAVAGLIA Universidad Nacional del Centro Juan Carlos GROSSO Universidad Nacional del Centro Universidad Autónoma de Puebla INTRODUCCIÓN EN ESTE TRABAJO HEMOS ESTUDIADO la evolución de la población de la villa de Tepeaca y su entorno agrario durante el siglo que se extiende entre 1740 y 1850 —fechas que correspon den grosso modo al marco temporal comprendido entre las principales fuentes primarias analizadas, si bien, como com probará el lector, el estudio comienza antes y termina des pués de estas fechas límites— y las diferencias observadas en el comportamiento demográfico de los grupos étnicos y los diversos núcleos de población existentes en la parroquia. Sin aventurarnos en el análisis de los parámetros básicos del movimiento de la población, hemos intentado explicitar al gunos de los procesos ,o factores que influyeron en el com portamiento demográfico de la parroquia, tales como la mortalidad, las migraciones, la movilidad de recursos demo gráficos entre pueblos indígenas, barrios y haciendas, o las coyunturas bélicas y económicas. No está de más recordar que este trabajo se enmarca en un estudio más amplio de la * Este trabajo ha contado con el respaldo financiero del CONICET (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas) argentino, como parte del Programa de Investigación "Población y sociedad: estruc turas sociales y comportamiento demográfico en Hispanoamérica -

Alumna: Andrea Saleh Selman Profesor Guía: Manuel Amaya Noviembre 2010 I

alumna: Andrea Saleh Selman profesor guía: Manuel Amaya noviembre 2010 I. ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 4 CIUDAD 7 I. Situación general de la ciudad de Constitución 8 a. Reseña histórica: el balneario y la madera. 10 2 b. El potencial turístico de la ciudad y sus alrededores. 11 II. Situación post terremoto y tsunami 12 a. El impacto social y la necesidad de reformular el borde del río Maule 12 b. El PRES y su parque de mitigación 14 PATRIMONIO EL RAMAL TALCA - CONSTITUCIÓN 19 I. Valor patrimonial 20 a. Tren Talca - Constitución, el último ramal de Chile. 20 b. Valor histórico y social 21 c. Valor paisajístico y natural 22 d. Valor arquitectónico 24 II. Alcance y recuperación del patrimonio 27 TRANSPORTE 31 I. Conectividad 32 a. Transporte interurbano 32 b. Competitividad del tren como medio de transporte alternativo 36 Recuperación y fortalecimiento de la infraes- PROYECTO 39 tructura – consolidarlo como medio de trans- I. Terreno porte confiable y competitivo a. Posicionamiento urbano d. Orientación y captación del turista (surge como un efecto de los puntos anteriores) Condición de acceso Oficina de turismo – claridad de la oferta turísti- b. Emplazamiento y funcionamiento actual ca comunal en el punto de llegada. Virtudes a rescatar y problemas a resolver Orientación – relación espacial con el borde y el c. Daños en la infraestructura post terremoto y recorrido peatonal. tsunami III. Propuesta urbana La línea del tren, las estaciones, el terminal a. En relación al espacio público y la imagen ur- de buses y de tren bana d. Marco normativo aplicable b. En relación a la protección de un eventual 3 Nuevo plan regulador tsunami II. -

Crustal Deformation Associated with the 1960 Earthquake Events in the South of Chile

Paper No. CDDFV CRUSTAL DEFORMATION ASSOCIATED WITH THE 1960 EARTHQUAKE EVENTS IN THE SOUTH OF CHILE Felipe Villalobos 1 ABSTRACT Large earthquakes can cause significant subsidence and uplifts of one or two meters. In the case of subsidence, coastal and fluvial retaining structures may therefore no longer be useful, for instance, against flooding caused by a tsunami. However, tectonic subsidence caused by large earthquakes is normally not considered in geotechnical designs. This paper describes and analyses the 1960 earthquakes that occurred in the south of Chile, along almost 1000 km between Concepción and the Taitao peninsula. Attention is paid to the 9.5 moment magnitude earthquake aftermath in the city of Valdivia, where a tsunami occurred followed by the overflow of the Riñihue Lake. Valdivia and its surrounding meadows were flooded due to a subsidence of approximately 2 m. The paper presents hypotheses which would explain why today the city is not flooded anymore. Answers can be found in the crustal deformation process occurring as a result of the subduction thrust. Various hypotheses show that the subduction mechanism in the south of Chile is different from that in the north. It is believed that there is also an elastic short-term effect which may explain an initial recovery and a viscoelastic long-term effect which may explain later recovery. Furthermore, measurements of crustal deformation suggest that a process of stress relaxation is still occurring almost 50 years after the main seismic event. Keywords: tectonic subsidence, 1960 earthquakes, Valdivia, crustal deformation, stress relaxation INTRODUCTION Tectonic subsidence or uplift is not considered in any design of onshore or near shore structures. -

The Mw 8.8 Chile Earthquake of February 27, 2010

EERI Special Earthquake Report — June 2010 Learning from Earthquakes The Mw 8.8 Chile Earthquake of February 27, 2010 From March 6th to April 13th, 2010, mated to have experienced intensity ies of the gap, overlapping extensive a team organized by EERI investi- VII or stronger shaking, about 72% zones already ruptured in 1985 and gated the effects of the Chile earth- of the total population of the country, 1960. In the first month following the quake. The team was assisted lo- including five of Chile’s ten largest main shock, there were 1300 after- cally by professors and students of cities (USGS PAGER). shocks of Mw 4 or greater, with 19 in the Pontificia Universidad Católi- the range Mw 6.0-6.9. As of May 2010, the number of con- ca de Chile, the Universidad de firmed deaths stood at 521, with 56 Chile, and the Universidad Técni- persons still missing (Ministry of In- Tectonic Setting and ca Federico Santa María. GEER terior, 2010). The earthquake and Geologic Aspects (Geo-engineering Extreme Events tsunami destroyed over 81,000 dwell- Reconnaissance) contributed geo- South-central Chile is a seismically ing units and caused major damage to sciences, geology, and geotechni- active area with a convergence of another 109,000 (Ministry of Housing cal engineering findings. The Tech- nearly 70 mm/yr, almost twice that and Urban Development, 2010). Ac- nical Council on Lifeline Earthquake of the Cascadia subduction zone. cording to unconfirmed estimates, 50 Engineering (TCLEE) contributed a Large-magnitude earthquakes multi-story reinforced concrete build- report based on its reconnaissance struck along the 1500 km-long ings were severely damaged, and of April 10-17. -

Epidemiology of Dog Bite Incidents in Chile: Factors Related to the Patterns of Human-Dog Relationship

animals Article Epidemiology of Dog Bite Incidents in Chile: Factors Related to the Patterns of Human-Dog Relationship Carmen Luz Barrios 1,2,*, Carlos Bustos-López 3, Carlos Pavletic 4,†, Alonso Parra 4,†, Macarena Vidal 2, Jonathan Bowen 5 and Jaume Fatjó 1 1 Cátedra Fundación Affinity Animales y Salud, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, Parque de Investigación Biomédica de Barcelona, C/Dr. Aiguader 88, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 2 Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Mayor, Camino La Pirámide 5750, Huechuraba, Región Metropolitana 8580745, Chile; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Ciencias Básicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Santo Tomás, Av. Ejército Libertador 146, Santiago, Región Metropolitana 8320000, Chile; [email protected] 4 Departamento de Zoonosis y Vectores, Ministerio de Salud, Enrique Mac Iver 541, Santiago, Región Metropolitana 8320064, Chile; [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (A.P.) 5 Queen Mother Hospital for Small Animals, Royal Veterinary College, Hawkshead Lane, North Mymms, Hertfordshire AL9 7TA, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +56-02-3281000 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Simple Summary: Dog bites are a major public health problem throughout the world. The main consequences for human health include physical and psychological injuries of varying proportions, secondary infections, sequelae, risk of transmission of zoonoses and surgery, among others, which entail costs for the health system and those affected. The objective of this study was to characterize epidemiologically the incidents of bites in Chile and the patterns of human-dog relationship involved. The results showed that the main victims were adults, men. -

200911 Lista De EDS Adheridas SCE Convenio GM-Shell

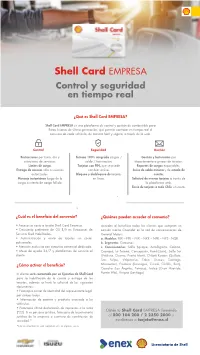

Control y seguridad en tiempo real ¿Qué es Shell Card EMPRESA? Shell Card EMPRESA es una plataforma de control y gestión de combustible para flotas livianas de última generación, que permite controlar en tiempo real el consumo de cada vehículo, de manera fácil y segura, a través de la web. Restricciones por hora, día y Sistema 100% integrado cargas / Gestión y facturación por estaciones de servicios. saldo / facturación. departamento o grupos de tarjetas. Límites de carga. Tarjetas con PIN, que se puede Reportes de cargas exportables. Entrega de accesos sólo a usuarios cambiar online. Aviso de saldo mínimo y de estado de autorizados. Bloqueo y desbloqueo de tarjetas cuenta. Mensaje instantáneo luego de la en línea. Solicitud de nuevas tarjetas a través de carga o intento de carga fallida. la plataforma web. Envío de tarjetas a todo Chile sin costo. ¿Cuál es el beneficio del convenio? ¿Quiénes pueden acceder al convenio? • Acceso sin costo a tarjeta Shell Card Empresa. Acceden al beneficio todos los clientes que compran un • Descuento preferente de -20 $/lt en Estaciones de camión marca Chevrolet en la red de concesionarios de Servicio Shell Habilitadas. General Motors. • Administración y envío de tarjetas sin costos a. Modelos: FRR – FTR – FVR – NKR – NPR – NPS - NQR. adicionales. b. Segmento: Camiones. • Atención exclusiva con ejecutivo comercial dedicado. c. Concesionarios: Salfa (Iquique, Antofagasta, Calama, • Mesa de ayuda 24/7 y plataformas de servicio al Copiapó, La Serena, Concepción, Rondizzoni), Salfa Sur cliente. (Valdivia, Osorno, Puerto Montt, Chiloé) Kovacs (Quillota, San Felipe, Valparaíso, Talca, Linares, Santiago, ¿Cómo activar el beneficio? Movicenter), Frontera (Rancagua, Curicó, Chillán, Buin), Coseche (Los Ángeles, Temuco), Inalco (Gran Avenida, El cliente será contactado por un Ejecutivo de Shell Card Puente Alto), Vivipra (Santiago). -

Viith NEOTROPICAL ORNITHOLOGICAL CONGRESS

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 13: 221–224, 2002 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society NEWS—NOTICIAS—NOTÍCIAS VIIth NEOTROPICAL ORNITHOLOGICAL CONGRESS Dates. – The VIIth Neotropical Ornitholog- although they know a few English words and ical Congress will take place from Sunday, attempts to communicate by non-Spanish 5 October through Saturday 11 October speakers will result in a meaningful exchange. 2003. Working days will be Monday 6, Puerto Varas has several outstanding restau- Tuesday 7, Wednesday 8, Friday 10, and rants (including sea food, several more ethnic Saturday 11 October 2003. Thursday 9 kinds of food, and, of course, Chilean fare). October 2003 will be a congress free day. In spite of its small size, Puerto Varas is quite After the last working session on Saturday 11 a cosmopolitan town, with a well-marked October, the congress will end with a ban- European influence. There are shops, bou- quet, followed by traditional Chilean music tiques, and other stores, including sporting and dance. goods stores. Congress participants will be able to choose from a variety of lodging alter- Venue. – Congress Center, in Puerto Varas, natives, ranging from luxury five-star estab- Xth Region, Chile (about 10 km N of Puerto lishments to ultra-economical hostels. Montt, an easy to reach and well-known Because our meeting will be during the “off ” travel destination in Chile. The Congress Cen- season for tourists, participants will be able to ter, with its meeting rooms and related facili- enjoy the town’s tourist-wise facilities and ties, perched on a hill overlooking Puerto amenities (e.g., the several cybercafes, compet- Varas, is only an 800-m walk from downtown itive money exchange businesses, and the where participants will lodge and dine in their many local tour offerings) without paying typ- selection of hotels, hostels, and eating facili- ical tourist prices. -

Campamentos: Factores Socioespaciales Vinculados a Su Persisitencia

UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE FACULTAD DE ARQUITECTURA Y URBANISMO ESCUELA DE POSTGRADO MAGÍSTER EN URBANISMO CAMPAMENTOS: FACTORES SOCIOESPACIALES VINCULADOS A SU PERSISITENCIA ACTIVIDAD FORMATIVA EQUIVALENTE PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE MAGÍSTER EN URBANISMO ALEJANDRA RIVAS ESPINOSA PROFESOR GUÍA: SR. JORGE LARENAS SALAS SANTIAGO DE CHILE OCTUBRE 2013 ÍNDICE DE CONTENIDOS Resumen 6 Introducción 7 1. Problematización 11 1.1. ¿Por qué Estudiar los Campamentos en Chile si Hay una Amplia Cobertura 11 de la Política Habitacional? 1.2. La Persistencia de los Campamentos en Chile, Hacia la Formulación de 14 una Pregunta de Investigación 1.3. Objetivos 17 1.4. Justificación o Relevancia del Trabajo 18 2. Metodología 19 2.1. Descripción de Procedimientos 19 2.2. Aspectos Cuantitativos 21 2.3. Área Geográfica, Selección de Campamentos 22 2.4. Aspectos Cualitativos 23 3. Qué se Entiende por Campamento: Definición y Operacionalización del 27 Concepto 4. El Devenir Histórico de los Asentamientos Precarios Irregulares 34 4.1. Callampas, Tomas y Campamentos 34 4.2. Los Programas Específicos de las Últimas Décadas 47 5. Campamentos en Viña del Mar y Valparaíso 55 5.1. Antecedentes de los Campamentos de la Región 55 5.2. Descripción de la Situación de los Campamentos de Viña del Mar y Valparaíso 60 1 5.3. Una Mirada a los Campamentos Villa Esperanza I - Villa Esperanza II y 64 Pampa Ilusión 6. Hacia una Perspectiva Explicativa 73 6.1. Elementos de Contexto para Explicar la Permanencia 73 6.1.1. Globalización y Territorio 73 6.1.2. Desprotección e Inseguridad Social 79 6.1.3. Nueva Pobreza: Vulnerabilidad y Segregación Residencial 84 6.2. -

Damage Assessment of the 2015 Mw 8.3 Illapel Earthquake in the North‑Central Chile

Natural Hazards https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3541-3 ORIGINAL PAPER Damage assessment of the 2015 Mw 8.3 Illapel earthquake in the North‑Central Chile José Fernández1 · César Pastén1 · Sergio Ruiz2 · Felipe Leyton3 Received: 27 May 2018 / Accepted: 19 November 2018 © Springer Nature B.V. 2018 Abstract Destructive megathrust earthquakes, such as the 2015 Mw 8.3 Illapel event, frequently afect Chile. In this study, we assess the damage of the 2015 Illapel Earthquake in the Coquimbo Region (North-Central Chile) using the MSK-64 macroseismic intensity scale, adapted to Chilean civil structures. We complement these observations with the analysis of strong motion records and geophysical data of 29 seismic stations, including average shear wave velocities in the upper 30 m, Vs30, and horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratios. The calculated MSK intensities indicate that the damage was lower than expected for such megathrust earthquake, which can be attributable to the high Vs30 and the low predominant vibration periods of the sites. Nevertheless, few sites have shown systematic high intensi- ties during comparable earthquakes most likely due to local site efects. The intensities of the 2015 Illapel earthquake are lower than the reported for the 1997 Mw 7.1 Punitaqui intraplate intermediate-depth earthquake, despite the larger magnitude of the recent event. Keywords Subduction earthquake · H/V spectral ratio · Earthquake intensity 1 Introduction On September 16, 2015, at 22:54:31 (UTC), the Mw 8.3 Illapel earthquake occurred in the Coquimbo Region, North-Central Chile. The epicenter was located at 71.74°W, 31.64°S and 23.3 km depth and the rupture reached an extent of 200 km × 100 km, with a near trench rupture that caused a local tsunami in the Chilean coast (Heidarzadeh et al. -

The Evolution of the Location of Economic Activity in Chile in The

Estudios de Economía ISSN: 0304-2758 [email protected] Universidad de Chile Chile Badia-Miró, Marc The evolution of the location of economic activity in Chile in the long run: a paradox of extreme concentration in absence of agglomeration economies Estudios de Economía, vol. 42, núm. 2, diciembre, 2015, pp. 143-167 Universidad de Chile Santiago, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=22142863007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative TheEstudios evolution de Economía. of the location Vol. 42 of -economic Nº 2, Diciembre activity in2015. Chile… Págs. / Marc143-167 Badia-Miró 143 The evolution of the location of economic activity in Chile in the long run: a paradox of extreme concentration in absence of agglomeration economies*1 La evolución de la localización de la actividad económica en Chile en el largo plazo: la paradoja de un caso de extrema concentración en ausencia de fuerzas de aglomeración Marc Badia-Miró** Abstract Chile is characterized as being a country with an extreme concentration of the economic activity around Santiago. In spite of this, and in contrast to what is found in many industrialized countries, income levels per inhabitant in the capital are below the country average and far from the levels in the wealthiest regions. This was a result of the weakness of agglomeration economies. At the same time, the mining cycles have had an enormous impact in the evolution of the location of economic activity, driving a high dispersion at the end of the 19th century with the nitrates (very concentrated in the space) and the later convergence with the cooper cycle (highly dispersed). -

Statistical Synthesis of Chile 2000 - 2004 Statistical Synthesis of Chile 2000 - 2004

Statistical Synthesis of Chile 2000 - 2004 Statistical Synthesis of Chile 2000 - 2004 Central Bank of Chile AUTHORITIES OF THE CENTRAL BANK OF CHILE (At 31 December 2004) CENTRAL BANK BOARD VITTORIO CORBO LIOI Governor JOSÉ DE GREGORIO REBECO Vice-Governor JORGE DESORMEAUX JIMÉNEZ Board Member JOSÉ MANUEL MARFÁN LEWIS Board Member MANAGERS MARÍA ELENA OVALLE MOLINA Board Member EDUARDO A RRIAGADA CARDINI Communications MABEL CABEZAS BULLEMORE Logistical Services and Security CECILIA FELIÚ CARRIZO CAMILO CARRASCO A LFONSO Human Resources General Manager JERÓNIMO GARCÍA CAÑETE MIGUEL ÁNGEL NACRUR GAZALI Informatics General Counsel PABLO GARCÍA SILVA Macroeconomic Analysis JOSÉ MANUEL GARRIDO BOUZO Financial Analysis LUIS A LEJANDRO GONZÁLEZ BANNURA DIVISION MANAGERS Accounting and Administration LUIS ÓSCAR HERRERA BARRIGA JUAN ESTEBAN LAVAL ZALDÍVAR Financial Policy Chief Counsel ESTEBAN JADRESIC MARINOVIC SERGIO LEHMANN BERESI International Affairs International Analysis CARLOS PEREIRA A LBORNOZ IVÁN EDUARDO MONTOYA LARA Management and Development General Treasurer RODRIGO V ALDÉS PULIDO GLORIA PEÑA T APIA Research Foreign Trade and Trade Policy JORGE PÉREZ ETCHEGARAY Monetary Operations CRISTIÁN SALINAS CERDA Internacional Investment KLAUS SCHMIDT-HEBBEL DUNKER Economic Research MARIO ULLOA LÓPEZ General Auditor RICARDO V ICUÑA POBLETE Information and Statistics Research 3 Central Bank of Chile TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL BACKGROUND 7 Location and area, boundaries, climate and natural resources 7 Temperature, rainfall and environmental pollution