Appearances and Grooming Standards As Sex Discrimination in the Workplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Steven Almaraz Candidate for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ______________________________________ Director Kurt Hugenberg ______________________________________ Reader Allen McConnell ______________________________________ Reader Jonathan Kunstman ______________________________________ Graduate School Representative Monica Schneider ABSTRACT APPARENT SOCIOSEXUAL ORIENTATION: FACIAL CORRELATES AND CONSEQUENCES OF WOMEN’S UNRESTRICTED APPEARANCE by Steven M. Almaraz People make quick work of forming a variety of impressions of one another based on minimal information. Recent work has shown that people are able to make judgments of others’ Apparent Sociosexual Orientation (ASO) – an estimation of how interested another person is in uncommitted sexual activity – based on facial information alone. In the present work, I used three studies to expand the understanding of this poorly understood facial judgment by investigating the dimensionality of ASO (Study 1), the facial predictors of ASO (Study 2), and the consequences of these ASO judgments on men’s hostility and benevolence towards women (Study 3). In Study 1, I showed that men’s judgments of women’s Apparent Sociosexual Orientation were organized into judgments of women’s appearance of unrestricted attitudes and desires (Intrapersonal ASO) and their appearance of unrestricted behaviors (Behavioral ASO). Study 2 revealed that more attractive and more dominant appearing women were perceived as more sexually unrestricted. In Study 3, I found that women who appeared to engage in more unrestricted behavior were subjected to increased benevolent sexism, though this effect was primarily driven by unrestricted appearing women’s attractiveness. However, women who appeared to have sexually unrestricted attitudes and desires were subjected to increased hostility, even when controlling for the effects of the facial correlates found in Study 2. -

The Élan Vital of DIY Porn

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 11, No. 1 (March 2015) The Élan Vital of DIY Porn Shaka McGlotten In this essay, I borrow philosopher Henri Bergson’s concept élan vital, which is translated as vital force or vital impetus, to describe the generative potential evident in new Do-It- Yourself (DIY) pornographic artifacts and to resist the trend to view porn as dead or dead- ening. Bergson employed this idea to challenge the mechanistic view of matter held by the biological sciences of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, a view that considered the stuff of life to be reducible to brute or inert matter. Bergson argued, rather, that matter, insofar as it undergoes continuous change, is itself alive and not because of an immaterial, animat- ing principle, but because this liveliness is intrinsic to matter itself. I use Bergson’s élan vi- tal to think through the liveliness of gay DIY porn and for its contribution to a visual his- tory of desire, for the ways it changes the relationships between consumers and producers of pornography, and the ways it realizes new ways of stretching the pornographic imagination aesthetically and politically. It’s Alive I jump between sites. I watch a racially ambiguous young man with thick, muscular legs standing in front of a nondescript bathtub. He whispers, “I’m so horny right now,” rub- bing his cock beneath red Diesel boxer briefs. He turns and pulls his underwear down, arching his back to reveal a hairy butt. Turning to the camera again he shows off his modestly equipped, but very hard, dick. -

Pearl Boy Vibrator

Pearl Boy Vibrator This is our biggest selling model in the vibrators. It is a multi-speed vibrator with rabbit clitoris stimulator and rotating pearls for internal stimulation. Ensuring your ultimate PLEASURE! The most popular and famous “orgasm machine” on the market for its price range is the Pearl Boy. Manufactured in Japan, this vibrator has durability and quality written all over it. Its functionality is very diverse and has a few functions available, making it a real favourite. The device is quiet, powerful and smooth, filling the top qualities looked for by women. The Pearl Boy has 2 slide controllers allowing you to increase or decrease intensity for your own personal pleasure. One is for the pearl rotation of the vibrators shaft giving you a stimulating internal sensation! The movement of the pearls rotating inside is very pleasurable, and for some, very stimulating for the G-Spot. The other slide control is for the clit tickler. The tickler on the Pearl Boy is purrrrfection! They have mastered the right balance of firmness in the V-shaped tickler which also, unlike many others, vibrates slightly from side to side giving you double the stimulation while speed adjustable. Due to the side to side motion of the tickler, this makes the Pearl Boy also an excellent vibrator to be used with a partner, giving them more ability to please you with this toy! Operates on 3 AA Batteries. Not Included Companion Products LUBE AA Batteries Helmet Hammer ©Intimate Whispers 2014-17 Gigi – The Rechargeable Silicone Toy When your GiGi arrives you will find it to be luxuriously packaged! The outside packaging will match the colour of the product inside. -

Deception in Facial Expressions of Pain

DECEPTION IN FACIAL EXPRESSIONS OF PAIN: STRATEGIES TO IMPROVE DETECTION by MARILYN LOUISE HILL B.A. (Honours), Queen's University, 1989 M.Sc, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1992 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Psychology We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA AUGUST 1996 © Marilyn Louise Hill, 1996 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) Abstract Research suggests that clinicians assign greater weight to nonverbal expression than to patients' self-report when judging the location and severity of their pain. However, it has also been found that pain patients are fairly successful at altering their facial expressions of pain, as their deceptive and genuine pain expressions show few differences in the frequency and intensity of pain-related facial actions. The general aim of the present research was to improve the detection of deceptive pain expressions using both an empirical and a clinical approach. The first study had an empirical focus to pain identification, and provided a more detailed description of genuine and deceptive pain expressions by using a more comprehensive range of facial coding procedures than previous research. -

Sexercising Our Opinion on Porn: a Virtual Discussion

Psychology & Sexuality ISSN: 1941-9899 (Print) 1941-9902 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpse20 Sexercising our opinion on porn: a virtual discussion Elly-Jean Nielsen & Mark Kiss To cite this article: Elly-Jean Nielsen & Mark Kiss (2015) Sexercising our opinion on porn: a virtual discussion, Psychology & Sexuality, 6:1, 118-139, DOI: 10.1080/19419899.2014.984518 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2014.984518 Published online: 22 Dec 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 130 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rpse20 Psychology & Sexuality, 2015 Vol.6,No.1,118–139, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2014.984518 Sexercising our opinion on porn: a virtual discussion Elly-Jean Nielsen* and Mark Kiss Department of Psychology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada (Received 1 May 2014; accepted 11 July 2014) A variety of pressing questions on the current topics and trends in gay male porno- graphy were sent out to the contributors of this special issue. The answers provided were then collated into a ‘virtual’ discussion. In a brief concluding section, the contributors’ answers are reflected upon holistically in the hopes of shedding light on the changing face of gay male pornography. Keywords: gay male pornography; gay male culture; bareback sex; pornography It is safe to say that gay male pornography has changed. Gone are the brick and mortar adult video stores with wall-to-wall shelves of pornographic DVDs and Blu-rays for rental and sale. -

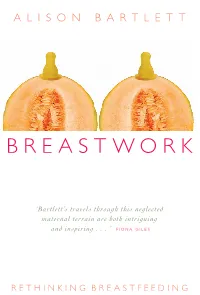

B R E a S T W O

BREASTWORK ALISON BARTLETT ‘BREASTWORK is a beautifully written and accessible guide to the many unexplored cultural meanings of breastfeeding in contemporary society. Of all our bodily functions, lactation is perhaps the most mysterious and least understood. Promoted primarily in terms of its nutritional benefi ts to babies, its place – or lack of it – in Western culture remains virtually unexplored. Bartlett’s travels through this neglected maternal terrain are both intriguing and inspiring, as she shows how breastfeeding can be a transformative act, rather than a moral duty. Looking at breastfeeding in relation to medicine, the media, sexuality, maternity and race, Bartlett’s study BREASTWORK provides a uniquely comprehensive overview of the ways in which we represent breastfeeding to ourselves and the many arbitrary limits we place around it. BREASTWORK makes a fresh, thoughtful and important contribution BARTLETT to the new area of breastfeeding and cultural studies. It is essential reading for ‘Bartlett’s travels through this neglected all students of the body, whether in the health professions, the social sciences, maternal terrain are both intriguing or gender and cultural studies – and for and inspiring . ’ F IONA GILES all mothers who have pondered the secrets of their own breastly intelligence.’ FIONA GILES author of Fresh Milk: The Secret Life of Breasts UNSW PRESS ISBN 0-86840-969-3 � UNSW RETHINKIN G BREASTFEEDING 9 780868 409696 � PRESS BreastfeedingCover2print.indd 1 29/7/05 11:44:52 AM BreastWork04 28/7/05 11:30 AM Page i BREASTWORK ALISON BARTLETT is the Director of the Centre for Women’s Studies at the University of Western Australia. -

Naughty Bingo Bingo Instructions

Naughty Bingo Bingo Instructions Host Instructions: · Decide when to start and select your goal(s) · Designate a judge to announce events · Cross off events from the list below when announced Goals: · First to get any line (up, down, left, right, diagonally) · First to get any 2 lines · First to get the four corners · First to get two diagonal lines through the middle (an "X") · First to get all squares (a "coverall") Guest Instructions: · Check off events on your card as the judge announces them · If you satisfy a goal, announce "BINGO!". You've won! · The judge decides in the case of disputes This is an alphabetical list of all 24 events: Anal, Anal Beads, Ass Whip, Ball Gag, Blindfold, Blowjob, Bukakke, Buttjob, Cowgirl/Reverse, Creampie, Dildo, Doggystyle, Face Down Ass Up, Facial, Hand Cuff, Irrumatio, Licky Licky, Mouth Gapper, Prostate Pro, Rough, Spank, Tied Up, Vibrating Anal Beads, Vibrator. BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved Naughty Bingo Bingo Call Sheet This is a randomized list of all 24 bingo events in square format that you can mark off in order, choose from randomly, or cut up to pull from a hat: Face Vibrating Mouth Down Anal Blindfold Facial Gapper Ass Up Beads Hand Irrumatio Creampie Anal Vibrator Cuff Blowjob Rough Dildo Buttjob Cowgirl/Reverse Anal Prostate Tied Up Doggystyle Ball Gag Beads Pro Licky Spank Ass Whip Bukakke Licky BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved B I N G O Vibrating Prostate Bukakke Doggystyle Blindfold Anal Pro Beads Mouth Vibrator Spank Dildo Ass Whip Gapper Anal Irrumatio Buttjob FREE Facial Beads Face Blowjob Creampie Rough Down Anal Ass Up Licky Hand Cowgirl/Reverse Ball Gag Tied Up Licky Cuff This bingo card was created randomly from a total of 24 events. -

For Sexual Health Care of Clinical

Clinical Guidelines for Sexual Health Care of Men Who Have Sex with Men Clinical ...for Sexual Health Care of IUSTI Asia Pacific Branch The Asia Pacific Branch of IUSTI is pleased to introduce a set of clinical guidelines for sexual health care of Men who have Sex with Men. This guideline consists of three types of materials as follows: 1. The Clinical Guidelines for Sexual Health Care of Men who Have Sex with Men (MSM) 2. 12 Patient information leaflets (Also made as annex of item 1 above) o Male Anogenital Anatomy o Gender Reassignment or Genital Surgery o Anogenital Ulcer o Genital Warts o What Infections Am I At Risk Of When Having Sex? o Hormone Therapy for Male To Female Transgender o How To Put On A Condom o Proctitis o What Can Happen To Me If I Am Raped? o Scrotal Swelling o What Does An STI & HIV Check Up Involve? o Urethral Discharge 3. Flip Charts for Clinical Management of Sexual Health Care of Men Who Have Sex with Men (Also made as an annex of item 1 above) The guidelines mentioned above were developed to assist the following health professionals in Asia and the Pacific in providing health care services for MSM: • Clinicians and HIV counselors who work in hospital outpatient departments, sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics, non-government organizations, or private clinics. • HIV counselors and other health care workers, especially doctors, nurses and counselors who care for MSM. • Pharmacists, general hospital staff and traditional healers. If you would like hard copies of the set of clinical guidelines for sexual health care of Men who have Sex with Men, please contact Dr. -

Court Green Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Court Green Publications 3-1-2013 Court Green: Dossier: Sex Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Court Green: Dossier: Sex" (2013). Court Green. 10. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Court Green by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Read good poetry!” —William Carlos Williams COURT GREEN 10 COURT 10 EDITORS Tony Trigilio and David Trinidad MANAGING EDITOR Cora Jacobs SENIOR EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Jessica Dyer EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS S’Marie Clay, Abby Hagler, Jordan Hill, and Eugene Sampson Court Green is published annually in association with Columbia College Chicago, Department of English. Our thanks to Ken Daley, Chair, Department of English; Deborah H. Holdstein, Dean, School of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Louise Love, Interim Provost; and Dr. Warrick Carter, President of Columbia College Chicago. Our submission period is March 1-June 30 of each year. Please send no more than five pages of poetry. We will respond by August 31. Each issue features a dossier on a particular theme; a call for work for the dossier for Court Green 11 is at the back of this issue. Submissions should be sent to the editors at Court Green, Columbia College Chicago, Department of English, 600 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60605. -

Perception of Sexual Orientation from Facial Structure: a Study with Artificial Face Models

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositori Institucional de la Universitat Jaume I Arch Sex Behav DOI 10.1007/s10508-016-0929-6 ORIGINAL PAPER Perception of Sexual Orientation from Facial Structure: A Study with Artificial Face Models Julio Gonza´lez-A´ lvarez1 Received: 19 July 2015 / Revised: 21 September 2016 / Accepted: 26 December 2016 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2017 Abstract Researchhasshownthatlaypeople canperceivesex- Introduction ual orientation better than chance from face stimuli. However, the relation between facial structure and sexual orientation has Animportantissueinpersonperceptionisthecategorizationof beenscarcelyexamined.Recently,anextensivemorphometric people into perceptually ambiguous groups in the absence of study on a large sample of Canadian people (Skorska, Geniole, obvious clues. Age, sex, race, for example, are easily inferred Vrysen, McCormick, & Bogaert, 2015) identified three (in men) when two individuals meet for the first time, but other features and four (in women) facial features as unique multivariate pre- such as professions, religious/political affiliations, or sexual dictors of sexual orientation in each sex group. The present orientation are perceptually elusive. The term‘‘gaydar’’(a lin- study tested the perceptual validity of these facial traits with guistic blend of gay and radar) refers to the popular belief that two experiments based on realistic artificial 3D face models heterosexual and gay/lesbian persons can be intuitively -

Affective Responses to Gay Men Using Facial Electromyography: Is There a Psychophysiological “Look” of Anti-Gay Bias

Journal of Homosexuality ISSN: 0091-8369 (Print) 1540-3602 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wjhm20 Affective Responses to Gay Men Using Facial Electromyography: Is There a Psychophysiological “Look” of Anti-Gay Bias Melanie A. Morrison, Krista M. Trinder & Todd G. Morrison To cite this article: Melanie A. Morrison, Krista M. Trinder & Todd G. Morrison (2018): Affective Responses to Gay Men Using Facial Electromyography: Is There a Psychophysiological “Look” of Anti-Gay Bias, Journal of Homosexuality, DOI: 10.1080/00918369.2018.1500779 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1500779 Published online: 13 Aug 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 56 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wjhm20 JOURNAL OF HOMOSEXUALITY https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1500779 Affective Responses to Gay Men Using Facial Electromyography: Is There a Psychophysiological “Look” of Anti-Gay Bias Melanie A. Morrison, PhD, Krista M. Trinder, MA, and Todd G. Morrison, PhD Department of Psychology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Despite a wealth of attitudinal studies that elucidate the psy- Affect; gay men; prejudice; chological correlates of anti-gay bias, studies that provide discrimination; facial EMG; evidence of the physiological correlates of anti-gay bias remain IAT; homonegativity; relatively scarce. The present study addresses the under-repre- homophobia; sexual minority; behavior sentation of physiological research in the area of homonega- tivity by examining psychophysiological markers, namely the affective manifestations of anti-gay prejudice, and their corre- spondence with anti-gay behavior. -

VAGINA Vagina, Pussy, Bearded Clam, Vertical Smile, Beaver, Cunt, Trim, Hair Pie, Bearded Ax Wound, Tuna Taco, Fur Burger, Cooch

VAGINA vagina, pussy, bearded clam, vertical smile, beaver, cunt, trim, hair pie, bearded ax wound, tuna taco, fur burger, cooch, cooter, punani, snatch, twat, lovebox, box, poontang, cookie, fuckhole, love canal, flower, nana, pink taco, cat, catcher's mitt, muff, roast beef curtains, the cum dump, chocha, black hole, sperm sucker, fish sandwich, cock warmer, whisker biscuit, carpet, love hole, deep socket, cum craver, cock squeezer, slice of heaven, flesh cavern, the great divide, cherry, tongue depressor, clit slit, hatchet wound, honey pot, quim, meat massager, chacha, stinkhole, black hole of calcutta, cock socket, pink taco, bottomless pit, dead clam, cum crack, twat, rattlesnake canyon, bush, cunny, flaps, fuzz box, fuzzy wuzzy, gash, glory hole, grumble, man in the boat, mud flaps, mound, peach, pink, piss flaps, the fish flap, love rug, vadge, the furry cup, stench-trench, wizard's sleeve, DNA dumpster, tuna town, split dick, bikini bizkit, cock holster, cockpit, snooch, kitty kat, poody tat, grassy knoll, cold cut combo, Jewel box, rosebud, curly curtains, furry furnace, slop hole, velcro love triangle, nether lips, where Uncle's doodle goes, altar of love, cupid's cupboard, bird's nest, bucket, cock-chafer, love glove, serpent socket, spunk-pot, hairy doughnut, fun hatch, spasm chasm, red lane, stinky speedway, bacon hole, belly entrance, nookie, sugar basin, sweet briar, breakfast of champions, wookie, fish mitten, fuckpocket, hump hole, pink circle, silk igloo, scrambled eggs between the legs, black oak, Republic of Labia,