Prevalence of Pediatric Rickets in Kenya[Version 2; Referees: 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Name: Isaiah Bosire Omosa Sex: Male Date of birth: 8th April 1974 Passport number: A037571 Nationality: Kenyan Profession: Civil and Environmental Engineer Address: Kenyatta University, Department of Civil Engineering, P.O Box 43844-00100, Thika Road, Nairobi, Kenya. OR P.O Box 966-00520 (Ruai) Nairobi. E-mail: [email protected] Membership in Professional Societies -Registered Graduate Engineer, Engineers’ Registration Board of Kenya. -Graduate Member, Institution of Engineers of Kenya. Education 2009-2013 Doctor of Engineering ( Environmental Science), UNEP-TongJi, Institute of Environment for Sustainable Development, TongJi University, Shanghai, China. Doctoral Research Topic: Tertiary Treatment of Municipal Wastewater Using Horizontal Subsurface Flow Constructed Wetlands and UV irradiation- with reference to Kenya. 1999-2005 Master of Science (MSc.) in Civil Engineering (Environmental Health Engineering option), University of Nairobi, Kenya. M.Sc. Thesis Title: Assessment of the biological treatability of black tea processing effluent 1993-1998 Bachelor of Science (B.Sc Hons) in Civil Engineering, University of Nairobi, Kenya. Employment Records 1999-2002 Masosa construction Ltd, Projects Engineer 2004 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Research Assistant (Internship) 2005 - 2006 Ministry of Roads and Public Works, Civil Engineer (Storm Water drainage, Sewerage/Foul water drainage and Estate Roads design and construction supervision). 2009-2011 Kenyatta University, Water & Environmental Engineering Department, Tutorial Fellow / Assistant Lecturer. 2011- to date Kenyatta University, Civil Engineering Department, Lecturer. Professional Experience 2001 Research on a study of water demand management for the City of Nairobi under the ‘Managing water for African Cities’ project undertaken by UN- Habitat/Nairobi City Council. 2002 Site Agent on El nino emergency repairs and extensions to Kisii, Keroka and Gesusu Water supplies in Kisii District (Contract No. -

Download List of Physical Locations of Constituency Offices

INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION PHYSICAL LOCATIONS OF CONSTITUENCY OFFICES IN KENYA County Constituency Constituency Name Office Location Most Conspicuous Landmark Estimated Distance From The Land Code Mark To Constituency Office Mombasa 001 Changamwe Changamwe At The Fire Station Changamwe Fire Station Mombasa 002 Jomvu Mkindani At The Ap Post Mkindani Ap Post Mombasa 003 Kisauni Along Dr. Felix Mandi Avenue,Behind The District H/Q Kisauni, District H/Q Bamburi Mtamboni. Mombasa 004 Nyali Links Road West Bank Villa Mamba Village Mombasa 005 Likoni Likoni School For The Blind Likoni Police Station Mombasa 006 Mvita Baluchi Complex Central Ploice Station Kwale 007 Msambweni Msambweni Youth Office Kwale 008 Lunga Lunga Opposite Lunga Lunga Matatu Stage On The Main Road To Tanzania Lunga Lunga Petrol Station Kwale 009 Matuga Opposite Kwale County Government Office Ministry Of Finance Office Kwale County Kwale 010 Kinango Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Floor,At Junction Off- Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Kinango Ndavaya Road Floor,At Junction Off-Kinango Ndavaya Road Kilifi 011 Kilifi North Next To County Commissioners Office Kilifi Bridge 500m Kilifi 012 Kilifi South Opposite Co-Operative Bank Mtwapa Police Station 1 Km Kilifi 013 Kaloleni Opposite St John Ack Church St. Johns Ack Church 100m Kilifi 014 Rabai Rabai District Hqs Kombeni Girls Sec School 500 M (0.5 Km) Kilifi 015 Ganze Ganze Commissioners Sub County Office Ganze 500m Kilifi 016 Malindi Opposite Malindi Law Court Malindi Law Court 30m Kilifi 017 Magarini Near Mwembe Resort Catholic Institute 300m Tana River 018 Garsen Garsen Behind Methodist Church Methodist Church 100m Tana River 019 Galole Hola Town Tana River 1 Km Tana River 020 Bura Bura Irrigation Scheme Bura Irrigation Scheme Lamu 021 Lamu East Faza Town Registration Of Persons Office 100 Metres Lamu 022 Lamu West Mokowe Cooperative Building Police Post 100 M. -

ESIA 1279 Ruiru II Dam Report

ATHI WATER SERVICES BOARD RUIRU II DAM WATER SUPPLY PROJECT ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY REPORT JULY 2016 Environmental Safeguards Consultants (ESC) Limited Page | 1 If you have to print, we suggest you use, for economic and ecological reasons, double‐sided printas much as possible. Page | 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................9 Project Background............................................................................................................................ 9 Project Need and Justification............................................................................................................ 9 The ESIA Study and Objective .......................................................................................................... 9 Project Description and Components................................................................................................. 9 Project Cost...................................................................................................................................... 11 ESIA Approach and Methodology................................................................................................... 11 Public Consultation, Participation and Disclosure........................................................................... 12 Policy, Legal and Administrative -

Determinants of Implementation of Drought Mitigative Measures in Kenya

Paper Title: Determinants of implementation of drought mitigative measures in Kenya. Karuri, Thiongo, Postdoc Researcher, Mount Kenya University (www.mku.ac.ke) Member, YESS-COMMUNITY (www.yess-community.org) [email protected], [email protected], Moi Avenue 13654 00100, Nairobi Kenya. +254(0)722882436 Abstract. A drought is a slow onset climatic event that cannot be totally eradicated but interventions can be made to be better prepared to cope with drought, develop more resilient ecosystems to recover from drought episodes and mitigate the impacts of droughts. Sustainable Development interventions can go a long way in enhancing drought mitigation and adaptation in developing nations and world as well. The two are closely intertwined and efforts in one are area build multiple synergies for the other. Drought mitigation measures are those interventions that eliminate or reduce the drought impacts and risks. The objective of this project is to investigate the determinants of implementation of drought mitigation measures Ndalani ward, Machakos County. The specific objectives include investigating the effects of staff skills implementation of drought mitigation measures; to investigate the effects of users’ information on the implementation of drought mitigation measures and to investigate the effect of donors on implementation of drought mitigation measures Ndalani ward. A descriptive survey research design was adopted in this study; this enabled the research to give a detailed description of the research variables. The target population was 96 farmers from Ndalani ward in the larger Yatta area. Data collection was done by use of questionnaires with open and closed-ended questionnaires. Data were tallied, analyzed through XLstat and presented using frequency tables and figures. -

The Kenya Gazette

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaperat theG.P.0.) Vol. CV—No.58 NAIROBI, 30th May, 2003 Price Sh. 40 GAZETTE NOTICE NO.3629 THE TRANSPORT LICENSING ACT (Cap. 404) APPLICATIONS THEundermentioned applications will be considered by the Transport Licensing Board at Kenyatta International Conference Centre on the following days: Monday, 9th June, 2003—NB/R/03/2/01 to’ NB/R/03/2/100. Tuesday, 10th June, 2003—NB/B/03/2/101 to NB/R/03/2/200. Wednesday, 11th June, 2003 . Thursday, 12th June, 2003 —+} to consider deferred cases and renewals for the year 2003. Friday, 13th June, 2003 Every objection in respect of an application shall be lodged with the licensing authority and the District Commissionerof the district in which such an application is to be heard and a copytherefore shall be sent to the applicant not less than seven (7) days before the date of the meeting at which such an application is to be heard. Objections received later will not be considered except where otherwise stated that the applications are for one vehicle. Every objectorshall include the registration numberof his/her vehicle (together with the timetables where applicable). operating on the applicant's proposed route. Those who submitapplications in the names of partnership and companies must bring certificates of business registration to the Transport Licensing Board meeting. Applicants who are Kenya, Tanzania or Ugandacitizens of non-African origin must producetheir certificates or any other documentary proofof their citizenship. : Applicants who fail to attend the above meeting as per requirementofthis notice, without a reasonable cause, will have their applications refused and should therefore, not expect further communications from the Board. -

Municipal Managers Positions.Pdf

COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KIAMBU COUNTY PUBLIC SERVICE BOARD P.O BOX 2362-00900 KIAMBU VACANCIES FOR MUNICIPAL MANAGERS (6 POSTS) Pursuant to the provisions of Section 28 and 29 of the Urban Areas and Cities Act, 2011, the County Public Service Board wishes to recruit competent and qualified persons to fill the following positions of Municipal Managers for any of the following proposed Municipalities: Kiambu, Karuri, Thika, Kikuyu, Limuru and Ruiru. The Municipal Manager shall hold office for a contractual term of three years, which term may be renewed based on performance. Duties and Responsibilities The Municipal Manager shall be responsible for implementing the Municipal Board's decisions. Requirements for Appointment A person may be eligible for this position if that person; Is a Kenyan citizen; Holder of a degree from a University recognized in Kenya; Has a proven experience of not less than five years in administration or management either in the public or private sector; and Satisfy the requirements of Chapter six of the Constitution of Kenya 2010. Terms of employment: Contract Salary: As per Salaries and Remuneration Commission (SRC) Recommendations. 1 How to apply All applicants should submit their applications together with copies of their detailed curriculum vitae with names, address and telephone contacts of three referees. Academic and professional certificates, testimonials, national identity card or passport and any other supporting documents. Clearly indicate the Municipality applied for both on the cover letter and the envelope. Applications should be addressed to: The Secretary County Public Service Board P O Box 2362 - 00900 KIAMBU Hand delivered applications should be dropped in the specific box provided on the first floor Thika Sub-County offices (at the County Public Service Board offices - Room 103) between 8.00 a.m and 5.00 p.m on weekdays. -

Karuri Municipality Spatial Plan (Intergrated Urban Development Plan)

KARURI MUNICIPALITY SPATIAL PLAN (INTERGRATED URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN) KENYA URBAN SUPPORT PROGRAMME (KUSP) Naomi Mirithu Director Municipal Administration & Urban Development. Martin Kangiri Project Coordinator Eric Matata Urban Planning and Management. Josephine Wangui Social Development. Keziah Mbugua Capacity Development. Jennifer Kamzeh GIS Expert. Maureen Gitonga Budget Officer. Clare Wanjiku Procurement Officer. Samuel Mathu Procurement Officer. Hannah Njeri Communications. James Njoroge Accountant. Eng. John Wachira Infrastructure expert . Prepared for the COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KIAMBU April 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Urbanization in Kenya.................................................................................................................. 7 2. Background information .............................................................................................................. 8 3. Project beneficiaries ...................................................................................................................... 9 4. Background Information for the Karuri Municipality .......................................................... 11 5. The Rationale of the Assignment ............................................................................................... 14 6. Criteria for establishment of Municipalities as per Section 9 of the Urban Areas and Cities Act 16 6.1 Criteria 1: Population Threshold for the Karuri Municipality ..................................... 16 6.2 Criteria 2: Integrated Strategic Urban Development -

Kenya Urban Support Program

DOCUMENT OF THE WORLD BANK FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 117002-KE PROGRAM APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF US$300 MILLION TO THE Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF KENYA FOR THE KENYA URBAN SUPPORT PROGRAM July 5, 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Social, Urban, Rural, and Resilience Global Practice AFRICA “This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization.” Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective May 31, 2017) Currency Unit = Kenya Shillings KSH 103.40 = US$1 US$1.38 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR July 1 – June 30 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS APA Annual Performance Assessment CARA County Allocation of Revenue Act CEC County Executive Committee CIDP County Integrated Development Plan CoB Controller of Budget CoG Council of Governors CPCT County Program Coordination Team CPS Country Partnership Strategy CRA Commission on Revenue Allocation CUIDS County Urban Institutional Development Strategy DLI Disbursement Linked Indicator DORA Division of Revenue Act EACC Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESSA Environment and Social Systems Assessment FM Financial Management GDP Gross Domestic Product GRS Grievance Redress Service IDeP Integrated Development Plan IFMIS Integrated Financial Management Information System IFR Interim -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered As a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) � Vol

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR LAW REPORTING LIBRARY SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXXII —No. 189 NAIROBI, 16th October, 2020 Price Sh, 60 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 8258 CAUSE No. 409 OF 2020 IN THE HIGH COURT OF KENYA AT NAIROBI By (1) Humphrey Mwithiga Kanja and (2) Charles Ndungu Kanja, both of P.O. Box 51-00902, Kikuyu in Kenya, the deceased's sons, for PROBATE AND ADMINISTRATION a grant of letters of administration intestate to the estate of Monica Mirigo alias Mirigo Njoroge Cheche alias Monicah Merigo Kanja, late TAKE NOTICE that applications having been made in this court of Kiambu, who died at Masaba Hospital in Kenya, on 25th January, in: 2003. CAUSE No. 43 OF 2020 CAUSE No. E358 OF 2020 By (1) Paresh Kanji Patel alias Paresh Kanji Kalyan Patel and (2) By Nyokabi Elizabeth Kanaiya, of P.O. Box 24698-00502, Mahesh Kanji Patel alias Mahesh Kanji Kalyan Patel, both of P.O. Nairobi in Kenya, the deceased's's sister, through Messrs. Ranja & Box 5669-00506, Nairobi in Kenya, the executors named in the Co., advocates of Nairobi, for a grant of letters of administration deceased's last will, through Messrs. Taibjee & Bhalla, advocates intestate to the estate of Christiana Waigumo Sarah Kanaiya, late of LLP of Nairobi, for a grant of probate of written will of Kanji Kalyan Mukurwe-ini, who died at Avenue Hospital in Kenya, on 17th Naran Patel alias Kanji Kalyan Patel, late of Nairobi, who died at October, 2019. -

Government Systems

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized DEVOLUTION WITHOUT DEVOLUTION Pathways to a successful newKenya asuccessful to Pathways DISRUPTION DISRUPTION DEVOLUTION WITHOUT DISRUPTION Pathways to a successful new Kenya November 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms and abbreviations i Foreword iii Acknowledgments iv Executive summary v Part I: Seeing the future from the perspective of the past Chapter 1: Kenya’s devolution in context 4 A turning point in a long historical process 4 Deep-rooted political economy dynamics 6 Chapter 2: The scale, scope and complexity of Kenya’s devolution 12 How the public sector functions today, and where it has failed 12 How the public sector will function after devolution 13 Implications of the transformation for public administration and service delivery 14 Implications for governance and the role of Parliament 17 Chapter 3: Demographic and geographic diversity of Kenya’s counties 20 Midgets and giants: Wide variations in population, density and urbanization 20 Poverty disparities, service inequities and social outcomes 21 Dealing with patterns of marginalization 24 Part II: Equity between levels of Government Chapter 4: Why it all starts with function assignment 30 Designing a framework for function assignment across levels of government 32 Clarifying function assignments 36 Guiding the function assignment process successfully 40 Refining function assignment going forward 44 Chapter 5: Determining how much counties need 46 Determining -

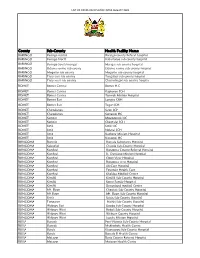

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye -

2019/2020 Supplementary Estimates Ii (Development Expenditure)

2019/2020 SUPPLEMENTARY ESTIMATES II (DEVELOPMENT EXPENDITURE) ESTIMATE of further sums required to be voted for the service of the year ending 30th June, 2020 VOLUME II (VOTES D1091-D1095) APRIL, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Expenditure Summary Development ……….……………...……………………. (ii) VOLUME I 1011 The Presidency ………………………………………………………………………....... 1 1021 State Department for Interior ……...…………………………………………………….. 36 1023 State Department for Correctional Services ……………………………………………... 102 1024 State Department for Immigration and Citizen Services ………………………………… 193 1032 State Department for Devolution ………………………………………………………... 208 1035 State Department for Development of the ASAL ……………………………………….. 216 1041 Ministry of Defence ….………………………………………………………………….. 231 1052 Ministry of Foreign Affairs ……………………………………….....………………….. 238 1064 State Department for Vocational and Technical Training ………..……………………… 262 1065 State Department for University Education ………………………….………………….. 407 1066 State Department for Early Learning & Basic Education ……………………………….. 456 1071 The National Treasury ………………………………………………….………………... 485 1072 State Department for Planning ……………………………………….………………….. 535 1081 Ministry of Health …………………………………………....……….…………………. 558 VOLUME II 1091 State Department for Infrastructure ………………………………….……….....……….. 599 1092 State Department for Transport …………………………………………….…………..... 1070 1093 State Department for Shipping and Maritime ……………………………………………. 1093 1094 State Department for Housing & Urban Development ……………………..……………. 1101 1095 State Department