Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Argonautica, Book 1;

'^THE ARGONAUTICA OF GAIUS VALERIUS FLACCUS (SETINUS BALBUS BOOK I TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY H. G. BLOMFIELD, M.A., I.C.S. LATE SCHOLAR OF EXETER COLLEGE, OXFORD OXFORD B. H. BLACKWELL, BROAD STREET 1916 NEW YORK LONGMANS GREEN & CO. FOURTH AVENUE AND 30TH STREET TO MY WIFE h2 ; ; ; — CANDIDO LECTORI Reader, I'll spin you, if you please, A tough yarn of the good ship Argo, And how she carried o'er the seas Her somewhat miscellaneous cargo; And how one Jason did with ease (Spite of the Colchian King's embargo) Contrive to bone the fleecy prize That by the dragon fierce was guarded, Closing its soporific eyes By spells with honey interlarded How, spite of favouring winds and skies, His homeward voyage was retarded And how the Princess, by whose aid Her father's purpose had been thwarted, With the Greek stranger in the glade Of Ares secretly consorted, And how his converse with the maid Is generally thus reported : ' Medea, the premature decease Of my respected parent causes A vacancy in Northern Greece, And no one's claim 's as good as yours is To fill the blank : come, take the lease. Conditioned by the following clauses : You'll have to do a midnight bunk With me aboard the S.S. Argo But there 's no earthly need to funk, Or think the crew cannot so far go : They're not invariably drunk, And you can act as supercargo. — CANDIDO LECTORI • Nor should you very greatly care If sometimes you're a little sea-sick; There's no escape from mal-de-mer, Why, storms have actually made me sick : Take a Pope-Roach, and don't despair ; The best thing simply is to be sick.' H. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

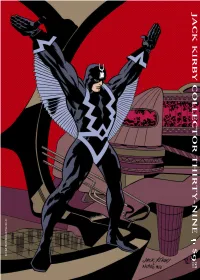

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR THIRTY-NINE $9 95 IN THE US . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M 3 0 0 2 © & M T t l o B k c a l B FAN FAVORITES! THE NEW COPYRIGHTS: Angry Charlie, Batman, Ben Boxer, Big Barda, Darkseid, Dr. Fate, Green Lantern, RETROSPECTIVE . .68 Guardian, Joker, Justice League of America, Kalibak, Kamandi, Lightray, Losers, Manhunter, (the real Silver Surfer—Jack’s, that is) New Gods, Newsboy Legion, OMAC, Orion, Super Powers, Superman, True Divorce, Wonder Woman COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .78 TM & ©2003 DC Comics • 2001 characters, (some very artful letters on #37-38) Ardina, Blastaar, Bucky, Captain America, Dr. Doom, Fantastic Four (Mr. Fantastic, Human #39, FALL 2003 Collector PARTING SHOT . .80 Torch, Thing, Invisible Girl), Frightful Four (Medusa, Wizard, Sandman, Trapster), Galactus, (we’ve got a Thing for you) Gargoyle, hercules, Hulk, Ikaris, Inhumans (Black OPENING SHOT . .2 KIRBY OBSCURA . .21 Bolt, Crystal, Lockjaw, Gorgon, Medusa, Karnak, C Front cover inks: MIKE ALLRED (where the editor lists his favorite things) (Barry Forshaw has more rare Kirby stuff) Triton, Maximus), Iron Man, Leader, Loki, Machine Front cover colors: LAURA ALLRED Man, Nick Fury, Rawhide Kid, Rick Jones, o Sentinels, Sgt. Fury, Shalla Bal, Silver Surfer, Sub- UNDER THE COVERS . .3 GALLERY (GUEST EDITED!) . .22 Back cover inks: P. CRAIG RUSSELL Mariner, Thor, Two-Gun Kid, Tyrannus, Watcher, (Jerry Boyd asks nearly everyone what (congrats Chris Beneke!) Back cover colors: TOM ZIUKO Wyatt Wingfoot, X-Men (Angel, Cyclops, Beast, n their fave Kirby cover is) Iceman, Marvel Girl) TM & ©2003 Marvel Photocopies of Jack’s uninked pencils from Characters, Inc. -

Ovid Book 12.30110457.Pdf

METAMORPHOSES GLOSSARY AND INDEX The index that appeared in the print version of this title was intentionally removed from the eBook. Please use the search function on your eReading device to search for terms of interest. For your reference, the terms that ap- pear in the print index are listed below. SINCE THIS index is not intended as a complete mythological dictionary, the explanations given here include only important information not readily available in the text itself. Names in parentheses are alternative Latin names, unless they are preceded by the abbreviation Gr.; Gr. indi- cates the name of the corresponding Greek divinity. The index includes cross-references for all alternative names. ACHAMENIDES. Former follower of Ulysses, rescued by Aeneas ACHELOUS. River god; rival of Hercules for the hand of Deianira ACHILLES. Greek hero of the Trojan War ACIS. Rival of the Cyclops, Polyphemus, for the hand of Galatea ACMON. Follower of Diomedes ACOETES. A faithful devotee of Bacchus ACTAEON ADONIS. Son of Myrrha, by her father Cinyras; loved by Venus AEACUS. King of Aegina; after death he became one of the three judges of the dead in the lower world AEGEUS. King of Athens; father of Theseus AENEAS. Trojan warrior; son of Anchises and Venus; sea-faring survivor of the Trojan War, he eventually landed in Latium, helped found Rome AESACUS. Son of Priam and a nymph AESCULAPIUS (Gr. Asclepius). God of medicine and healing; son of Apollo AESON. Father of Jason; made young again by Medea AGAMEMNON. King of Mycenae; commander-in-chief of the Greek forces in the Trojan War AGLAUROS AJAX. -

The Iphis Incident: Ovid's Accidental Discovery of Gender Dysphoria

Athens Journal of History - Volume 7, Issue 2, April 2021 – Pages 95-116 The Iphis Incident: Ovid’s Accidental Discovery of Gender Dysphoria By Ken Moore* This article examines what the author argues is Ovid's accidental discovery of gender dysphoria with recourse to an incident in the Metamorphoses. The author argues that Ovid has accidentally discovered gender dysphoria as evidenced through the character of Iphis in Book IX of the Metamorphoses. It is unlikely that Ovid could have imagined the ramifications of such a “discovery”; however, the “symptoms” described in his narrative match exceedingly closely with modern, clinical definitions. These are explored in the article along with how Ovid may have, through personal experience, been able to achieve such a penetrating, albeit accidental, insight. The wider, epistemological context of this topic is considered alongside Ovid's personal circumstances which may have contributed to his unique understanding of a condition that modern science has only recently identified. There are relatively few examples from ancient Greek and Roman literature that entail individuals having experienced something like the modern condition of transgenderism. One stands out above the others for sheer detail, along with emotional and psychological depth, that resonates quite well with issues faced by modernity. This is to be found in Ovid’s brief narrative about Iphis, at the end of book IX of the Metamorphoses. The text of this short episode is crucial in order to come to grips with this subject and I have included most of it here, in quotes as well as in appendices, as I deem it relevant to our understanding. -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

Homer's Use of Myth Françoise Létoublon

Homer’s Use of Myth Françoise Létoublon Epic and Mythology The Homeric Epics are probably the oldest Greek literary texts that we have,1 and their subject is select episodes from the Trojan War. The Iliad deals with a short period in the tenth year of the war;2 the Odyssey is set in the period covered by Odysseus’ return from the war to his homeland of Ithaca, beginning with his departure from Calypso’s island after a 7-year stay. The Trojan War was actually the material for a large body of legend that formed a major part of Greek myth (see Introduction). But the narrative itself cannot be taken as a mythographic one, unlike the narrative of Hesiod (see ch. 1.3) - its purpose is not to narrate myth. Epic and myth may be closely linked, but they are not identical (see Introduction), and the distance between the two poses a particular difficulty for us as we try to negotiate the the mythological material that the narrative on the one hand tells and on the other hand only alludes to. Allusion will become a key term as we progress. The Trojan War, as a whole then, was the material dealt with in the collection of epics known as the ‘Epic Cycle’, but which the Iliad and Odyssey allude to. The Epic Cycle however does not survive except for a few fragments and short summaries by a late author, but it was an important source for classical tragedy, and for later epics that aimed to fill in the gaps left by Homer, whether in Greek - the Posthomerica of Quintus of Smyrna (maybe 3 c AD), and the Capture of Troy of Tryphiodoros (3 c AD) - or in Latin - Virgil’s Aeneid (1 c BC), or Ovid’s ‘Iliad’ in the Metamorphoses (1 c AD). -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE the Motif of Fate In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Motif of Fate in Homeric Epics and Oedipus Tyrannus A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Chun Liu August 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Lisa Raphals, Chairperson Dr. Thomas Scanlon Dr. David Glidden The Dissertation of Chun Liu is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committee chair, Professor Lisa Raphals, whose guidance and support have been crucial to the completion of this dissertation. While the academic help she has offered me during the dissertation writing is invaluable, her excellent expertise in the field and indefatigable enthusiasm for her study set me a lifetime example. I would like to thank my committee members, Professor Thomas Scanlon and Professor David Glidden, who illuminated me not only in the writing and revision of the present work, but also in possible future projects. I benefited greatly from the many course-works and talks with Professor Scanlon. A special thank to Professor Glidden, for his kindness and patience, and for his philosophical perspective that broadened my scope. In addition, a thank you to Professor Wendy Raschke and Professor Benjamin King. For the past years they gave me solid trainings in the languages, read my proposals and gave many useful suggestions. I would also like to thank my parents and my friends in China who have always stood by me and cheered me up during the writing of this dissertation. iii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Motif of Fate in Homeric Epics and Oedipus Tyrannus by Chun Liu Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Comparative Literature University of California, Riverside, August 2010 Dr. -

Death and the Female Body in Homer, Vergil, and Ovid

DEATH AND THE FEMALE BODY IN HOMER, VERGIL, AND OVID Katherine De Boer Simons A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Depart- ment of Classics. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Sharon L. James James J. O’Hara William H. Race Alison Keith Laurel Fulkerson © 2016 Katherine De Boer Simons ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT KATHERINE DE BOER SIMONS: Death and the Female Body in Homer, Vergil, and Ovid (Under the direction of Sharon L. James) This study investigates the treatment of women and death in three major epic poems of the classical world: Homer’s Odyssey, Vergil’s Aeneid, and Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I rely on recent work in the areas of embodiment and media studies to consider dead and dying female bodies as representations of a sexual politics that figures women as threatening and even mon- strous. I argue that the Odyssey initiates a program of linking female death to women’s sexual status and social class that is recapitulated and intensified by Vergil. Both the Odyssey and the Aeneid punish transgressive women with suffering in death, but Vergil further spectacularizes violent female deaths, narrating them in “carnographic” detail. The Metamorphoses, on the other hand, subverts the Homeric and Vergilian model of female sexuality to present the female body as endangered rather than dangerous, and threatened rather than threatening. In Ovid’s poem, women are overwhelmingly depicted as brutalized victims regardless of their sexual status, and the female body is consistently represented as bloodied in death and twisted in metamorphosis. -

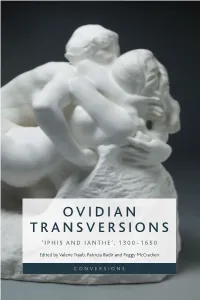

Ovidian Transversions Series Editors: Paul Yachnin and Bronwen Wilson

CONVERSIONS OVIDIAN TRANSVERSIONS OVIDIAN SERIES EDITORS: PAUL YACHNIN AND BRONWEN WILSON ‘A spectacular achievement. Harnessing the capacity of Ovid’s 1300–1650 AND IANTHE’, ‘IPHIS Iphis story to unsettle our categories of being and knowing, this book represents the very best in collaborative scholarship. It makes a truly transformational contribution to research on Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Ovidian reception, and the history and politics of embodiment, sexuality and gender.’ Robert Mills, University College London Focuses on transversions of Ovid’s ‘Iphis and Ianthe’ in both English and French literature Medieval and early modern authors engaged with Ovid’s tale of ‘Iphis and Ianthe’ in a number of surprising ways. From Christian translations to secular retellings on the seventeenth-century stage, Ovid’s story of a girl’s miraculous transformation into a boy sparked a diversity of responses in English and French from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries. In addition to analysing various translations and commentaries, the volume clusters essays around treatments of John Lyly’s Galatea (c.1585) and Issac de Benserade’s Iphis et Iante (1637). As a whole, the volume addresses gender and transgender, sexuality and gallantry, anatomy and alchemy, fable and history, youth and pedagogy, language and climate change. Badir and Peggy McCracken Patricia VALERIE TRAUB is author of Thinking Sex with the Early Moderns. Traub, Edited Valerie by PATRICIA BADIR is author of The Maudlin Impression: English Literary Images of Mary Magdalene, 1550–1700. PEGGY MCCRACKEN is author of In the Skin of a Beast: Sovereignty and Animality in Medieval France. OVIDIAN TRANSVERSIONS Cover image: Metamorphosis of Ovid; plaster statuette by Auguste Rodin; ca. -

Marvel Universe Thor Comic Reader 1 110 Marvel Universe Thor Comic Reader 2 110 Marvel Universe Thor Digest 110 Marvel Universe Ultimate Spider-Man Vol

AT A GLANCE Since it S inception, Marvel coMicS ha S been defined by hard-hitting action, co Mplex character S, engroSSing Story line S and — above all — heroi SM at itS fine St. get the Scoop on Marvel S’S MoSt popular characterS with thi S ea Sy-to-follow road Map to their greate St adventure S. available fall 2013! THE AVENGERS Iron Man! Thor! Captain America! Hulk! Black Widow! Hawkeye! They are Earth’s Mightiest Heroes, pledged to protect the planet from its most powerful threats! AVENGERS: ENDLESS WARTIME OGN-HC 40 AVENGERS VOL. 3: PRELUDE TO INFINITY PREMIERE HC 52 NEW AVENGERS: BREAKOUT PROSE NOVEL MASS MARKET PAPERBACK 67 NEW AVENGERS BY BRIAN MICHAEL BENDIS VOL. 5 TPB 13 SECRET AVENGERS VOL. 1: REVERIE TPB 10 UNCANNY AVENGERS VOL. 2: RAGNAROK NOW PREMIERE HC 73 YOUNG AVENGERS VOL. 1: STYLE > SUBSTANCE TPB 11 IRON MAN A tech genius, a billionaire, a debonair playboy — Tony Stark is many things. But more than any other, he is the Armored Avenger — Iron Man! With his ever-evolving armor, Iron Man is a leader among the Avengers while valiantly opposing his own formidable gallery of rogues! IRON MAN VOL. 3: THE SECRET ORIGIN OF TONY STARK BOOK 2 PREMIERE HC 90 THOR He is the son of Odin, the scion of Asgard, the brother of Loki and the God of Thunder! He is Thor, the mightiest hero of the Nine Realms and protector of mortals on Earth — from threats born across the universe or deep within the hellish pits of Surtur the Fire Demon. -

One of the Best Ways of Thinking About the Genesis of John Lyly's

BIBLID [1699-3225 (2007) 11, 207-218] A NEW MYTHOLOGICAL PATTERN FOR JOHN LYLY’S GALLATHEA: ACHILLES ON SCYROS1 One of the best ways of thinking about the genesis of John Lyly’s Gallathea2 is not so much in terms of sources, but rather in terms of patterns, because, like many other works of the Elizabethan Age, the play has been composed in the light of a series of precedents in the dramatic repertoire of the period and a series of patterns in Lyly’s reading of the classics. Indeed, in the first line of his play Lyly alerts his audience to the intimate relationship between his story and classical precedents, opening his action with an obvious quotation from the first line of Virgil’s first eclogue and naming some of his characters – Melebeus, Tityrus and Gallathea – after those of the Roman poet. He thus marks it as, in general, a work of the pastoral imagination, but, as Hunter3 has remarked, he immediately turns the political story of the eclogue into a mythological fantasy, drawing on other classical patterns, sometimes explicitly mentioned: Hesione, Polyphemus, and Iphis and Ianthe, whose precedent serves to solve the love tangle at the centre of the play. The alternative between an “honourable death” and an “infamous life” which exists for Phillida and Galatea, and the decision taken by Melibeus and Tityrus to disguise their daughters as boys in order to preserve their lives, suggests that Lyly also used the Achilles pattern of classical mythology, a hypothesis that I will try to demonstrate in this paper. -

The Iliad of Homer by Homer

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Iliad of Homer by Homer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Iliad of Homer Author: Homer Release Date: September 2006 [Ebook 6130] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ILIAD OF HOMER*** The Iliad of Homer Translated by Alexander Pope, with notes by the Rev. Theodore Alois Buckley, M.A., F.S.A. and Flaxman's Designs. 1899 Contents INTRODUCTION. ix POPE'S PREFACE TO THE ILIAD OF HOMER . xlv BOOK I. .3 BOOK II. 41 BOOK III. 85 BOOK IV. 111 BOOK V. 137 BOOK VI. 181 BOOK VII. 209 BOOK VIII. 233 BOOK IX. 261 BOOK X. 295 BOOK XI. 319 BOOK XII. 355 BOOK XIII. 377 BOOK XIV. 415 BOOK XV. 441 BOOK XVI. 473 BOOK XVII. 513 BOOK XVIII. 545 BOOK XIX. 575 BOOK XX. 593 BOOK XXI. 615 BOOK XXII. 641 BOOK XXIII. 667 BOOK XXIV. 707 CONCLUDING NOTE. 747 Illustrations HOMER INVOKING THE MUSE. .6 MARS. 13 MINERVA REPRESSING THE FURY OF ACHILLES. 16 THE DEPARTURE OF BRISEIS FROM THE TENT OF ACHILLES. 23 THETIS CALLING BRIAREUS TO THE ASSISTANCE OF JUPITER. 27 THETIS ENTREATING JUPITER TO HONOUR ACHILLES. 32 VULCAN. 35 JUPITER. 38 THE APOTHEOSIS OF HOMER. 39 JUPITER SENDING THE EVIL DREAM TO AGAMEMNON. 43 NEPTUNE. 66 VENUS, DISGUISED, INVITING HELEN TO THE CHAMBER OF PARIS.